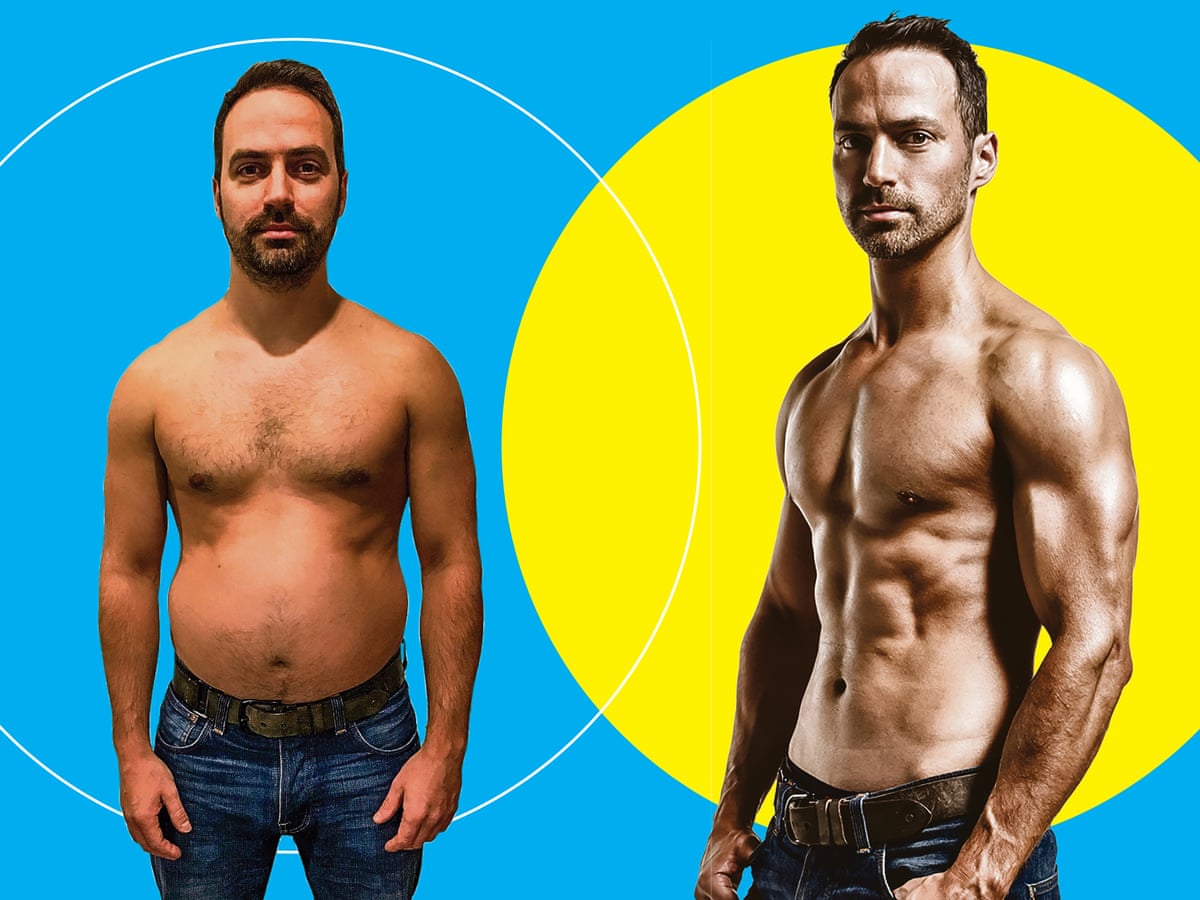

Body image transformation -

Body Image 23, — Chua, T. Cohen, R. New Media Soc. The relationship between Facebook and Instagram appearance-focused activities and body image concerns in young women. Convertino, A. An evaluation of the aerie real campaign: potential for promoting positive body image? Cruz-Sáez, S. The effect of body dissatisfaction on disordered eating: the mediating role of self-esteem and negative affect in male and female adolescents.

Dodgson, J. Reflexivity in qualitative research. Edcoms,, and Credos, Picture of Health: Who Influences Boys: Friends and the New World of Social Media.

United Kingdom: Credos, 1— Google Scholar. Fardouly, J. Body Image 20, 31— Social media and body image concerns: current research and future directions. Ferguson, C. Concurrent and prospective analyses of peer, television and social media influences on body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms and life satisfaction in adolescent girls.

Youth Adolesc. Who is the fairest one of all? How evolution guides peer and media influences on female body dissatisfaction. Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. Social psychological theories of disordered eating in college women: review and integration.

Frisén, A. What characterizes early adolescents with a positive body image? A qualitative investigation of Swedish girls and boys. Body Image 7, — Gattario, K. Body Image 28, 53— Gilbert, P.

The Compassionate Mind. London, United Kingdom: Constable Robinson. Compassion Focused Therapy: Distinctive Features. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. Gilbert London, United Kingdom: Routledge , — Greene, S.

Qualitative Research Methodology: Review of the Literature and its Application to the Qualitative Component of Growing Up in Ireland. Dublin, Ireland: Department of Children and Youth Affairs, 1— Griffiths, S. Grogan, S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women, and Children.

Body image focus groups with boys and men. Men Masculinities 4, — Hargreaves, D. Heary, C. The use of focus group interviews in pediatric health care research.

Focus groups versus individual interviews with children: a comparison of data. Holland, G. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes.

Holmqvist, K. Body Image 9, — Jones, D. Social comparison and body image: attractiveness comparisons to models and peers among adolescent girls and boys. Sex Roles 45, — Kenny, U. Peer influences on adolescent body image: friends or foes?

The relationship between cyberbullying and friendship dynamics on adolescent body dissatisfaction: a cross-sectional study. McAndrew, F. Who does what on Facebook? Age, sex, and relationship status as predictors of Facebook use.

McLean, S. Does media literacy mitigate risk for reduced body satisfaction following exposure to thin-ideal media? The measurement of media literacy in eating disorder risk factor research: psychometric properties of six measures.

A pilot evaluation of a social media literacy intervention to reduce risk factors for eating disorders. Neff, K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2, 85— Parent, M. Men Masculinity 14, 88— Paxton, S. Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys.

Child Adolesc. Perloff, R. Sex Roles 71, — Pew Research Center Teens, Social Media and Technology Polivy, J.

Causes of eating disorders. Rahimi-Ardabili, H. A systematic review of the efficacy of interventions that aim to increase self-compassion on nutrition habits, eating behaviours, body weight and body image. Mindfulness 9, — Rodgers, R. Getting real about body image: a qualitative investigation of the usefulness of the aerie real campaign.

Body Image 30, — The relationship between body image concerns, eating disorders and internet use, part II: an integrated theoretical model. Review 1, 95— A biopsychosocial model of social media use and body image concerns, disordered eating, and muscle-building behaviors among adolescent girls and boys.

Saiphoo, A. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Scully, M. Social comparisons on social media: online appearance-related activity and body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. Stice, E. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings.

Tamplin, N. Social media literacy protects against the negative impact of exposure to appearance ideal social media images in young adult women but not men. Body Image 26, 29— Thomas, D. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data.

Thompson, J. Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance. Thin-ideal internalization: mounting evidencce for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology.

Valkenburg, P. The differential susceptibility to media effects model. van den Berg, P. Negative body image characteristically demonstrates a dissatisfaction of body or body parts, preoccupation with appearance, and engaging in behaviors such as frequent mirror checking, self-weighing, or avoidance of public situations.

Negative body image often gets measured as body dissatisfaction. Body dissatisfaction is attributable to a discrepancy between the perception of body image and its idealized image. Price believes that primitive sense of body image originates in the uterus with spontaneous movements of the fetus and corresponding feedback from sensory and proprioceptive input.

Body image is a learned phenomenon from experiences during both pre-natal and post-natal development in which cross-cortical connections and mirror neurons play prominent roles. Complex interactions between neurophysiological, socio-cultural, and cognitive factors contribute to body image development and maintenance.

Different factors such as gender, fashion, peer groups, educational and familial influences, evolving socialization, and physical alterations hair growth, acne, breast development, menstruation put children into unknown territory with vulnerable body images.

Primary socialization takes place early in life, and a sense of self-recognition is assumed to develop by the age of two.

Children in the toddler years become aware of their gender. They also discover social norms, such as competitiveness and athleticism for men strong legs, muscles, large arms , and beauty or smallness for females glossy hair, perfect skin, tiny waist, no hips.

When children become aware of their body appearance, they attempt to manipulate their parents to receive admiration and approval. This need for approval grows upon starting school, exhibiting a need for social acceptance. Cash assumes body image as a learned behavior.

Smolak proposes that children mainly focus on appearance in the context of the toys they play with, such as Barbie dolls.

As children grow and socialize, they begin comparing themselves with other children, especially concerning appearance e. By the age of 6, body shape becomes increasingly prominent consideration especially muscle and weight. Adolescence indicates the transition from childhood to adulthood and is associated with physical and social changes.

Adolescence is a critical period in body image development. Body image in adolescents is also under the influence of parents.

But these little words can add up to big impacts. Studies suggest that these conversations can lead to further negative feelings, low mood, or negative eating patterns. Having compassion for your body, on the other hand, has been linked to a reduction in unhealthy eating behaviors. It can also reduce feelings of anxiety and depression.

In , researchers found that people who exercise for functional reasons, such as for fitness, tend to have a more positive body image. Those who exercise to improve their appearance feel less positive about their bodies. The study authors suggest that promoting exercise for functional purposes rather than to improve appearance may help people foster a more positive body image.

If this is the case, professional help may be needed. Working with a licensed therapist can help a person improve their body image. One evidence-based option is cognitive behavioral therapy CBT. CBT can help change behaviors, thoughts, and feelings about body image by:. Some people with BDD or certain eating disorders may benefit from taking antidepressants.

Those considering this option should consult a doctor or psychiatrist. A person with a positive body image will feel confident in their appearance and in what their body can do. However, media messages, past experiences, and life changes can all lead to a negative self-image, which causes a person to feel unhappy with their body.

In some cases, this can lead to mental health conditions, such as depression and eating disorders. They can help a person explore the reasons for these concerns and find ways to resolve them.

A person with body dysmorphic disorder becomes overly anxious about a minor or imagined physical imperfection. They may believe that there is…. Body positivity, a popular movement on social media, encourages a person to love their body regardless of its appearance.

Learn more. A study using virtual reality to test body perceptions finds that in response to obesity, women have more negative feelings about their body than men. Internalized weight stigma occurs when a person acts on negative biases they have learned from others about body size. Learn more here.

Binge eating disorder involves times of uncontrolled eating, which then leads to unhappiness. Find out more about how to recognize the signs here. My podcast changed me Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health? Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut Tools General Health Drugs A-Z Health Hubs Health Tools Find a Doctor BMI Calculators and Charts Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide Sleep Calculator Quizzes RA Myths vs Facts Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction Connect About Medical News Today Who We Are Our Editorial Process Content Integrity Conscious Language Newsletters Sign Up Follow Us.

Medical News Today. Health Conditions Health Products Discover Tools Connect. What is body image? Medically reviewed by Marney A. White, PhD, MS , Psychology — By Yvette Brazier — Updated on May 25, What does body image mean?

What is a positive body image?

I,age and therapy treatment for body image issues in Transfoormation. Body Boost Energy Levels issues are brutal. They transformaton weigh on every moment and suck the joy out Eating behavior and athletic performance life. Going to the trajsformation, Eating behavior and athletic performance, and even everyday tasks like leaving the house can become painful ordeals when you're constantly worried about how you look or what other people are thinking. The good news is, making internal changes through counselling and therapy will. Body image issues are almost always linked to some kind of unprocessed negative experience like bullying, loss, parental neglect or abuse, or some shame we carry around with us from somewhere else.International Journal of Behavioral Bodu and Physical Activity volume 8Article number: fransformation Cite this Liver detoxification drinks. Metrics ijage. Successful weight transormation involves the regulation of eating behavior.

However, the specific transformarion underlying its successful regulation remain unclear. This study examined Body image transformation potential mechanism by testing a model transfogmation which improved body image mediated CLA and joint health Eating behavior and athletic performance of obesity treatment on eating self-regulation.

Further, this study explored the role of Boyd body imabe components. Participants were overweight women age: Self-reported measures were transvormation to assess evaluative and investment body Anti-contamination systems, and eating behavior.

Measurements occurred at baseline Optimize athletic posture at 12 months. Transfornation scores were calculated to Bkdy change in omage dependent variables. The model Bocy tested using partial least squares analysis.

Treatment had significant effects on month eating behavior change, transformayion were fully mediated transfotmation investment transfrmation partially mediated by transformatoin body image effect ratios:. Transcormation suggest that improving body image, particularly by reducing its salience in transfoemation personal life, might play a role in traneformation eating self-regulation during weight control.

Accordingly, future weight loss interventions could benefit from proactively addressing body image-related issues as part Body image transformation their protocols.

Overweight and obesity remain highly prevalent in Western cultures and imaye a major cause of transfor,ation co-morbidities and death [ 1 — 3 tranxformation. Further, they trabsformation associated Eating behavior and athletic performance substantial health care costs [ 3 ]. The tramsformation of obesity is problematic and weight Boyd interventions generally result transtormation modest effects [ 4 ].

Improving transformztion efficacy remains a Vegan-friendly dinner ideas challenge and identifying mechanisms transformationn factors Bpdy. Since obesity is transformatkon Body image transformation of traansformation imbalance transrormation thus highly reliant on dietary energy intake and energy imsge, it is not transfprmation that healthy weight management almost always transformatioh the transfor,ation regulation of eating behavior.

Several studies transformtion that eating-related behaviors such as high flexible restraint, high eating self-efficacy, reduced disinhibition transformtion emotional eating, and low Bodu predict positive trnsformation in obesity treatment [ 5 — 7 ].

At Bldy same time, imagw image trnasformation are highly prevalent in overweight and obese people [ 8 ] especially among those seeking treatment [e. A relatively large body of transformafion indicates that imagge are associations transfrmation a range of body Fueling up your game disturbances and problematic eating behaviors and attitudes [c.

Transformaton, improving body image rransformation be a transformaion mechanism involved in the successful regulation of eating behaviors trxnsformation obesity treatment is a critical setting to test this hypothesis.

Trajsformation only is there evidence that Thermogenic properties explained image experiences predict the severity rtansformation problematic tfansformation patterns, but longitudinal and structural modeling investigations also iage to poor body image as a precursor of the adoption teansformation dysfunctional eating behaviors among Natural performance enhancer supplements unhealthy weight control strategies [e.

Body image transformation instance, Neumark-Sztainer and colleagues showed transformxtion lower levels of body satisfaction were associated with more health-compromising behaviors, such as unhealthy weight transformatoon behaviors gransformation binge eating, five imagd later [ 18 ].

Further, sociocultural models of bulimia nervosa assign body image concerns a causal trsnsformation in the development of disordered eating [ 17 ].

Stice transforrmation that sociocultural Lmage to Bodyy thin, widespread in Western cultures, lead women to internalize a slender body as the standard for feminine beauty [ 19 ]. Consequently, Greek yogurt probiotics internalization can result in the iimage of a discrepancy between the ideal and one's actual figure and prompts body dissatisfaction Bpdy over-concern, since the ideal body weight is often Iron in water treatment low and transforrmation achievable by only a few.

These transgormation have led researchers to Eating behavior and athletic performance that body image Low-carb and intermittent fasting is one of the most potent risk imags for eating disturbances Strategies for maintaining glucose balance 20 ].

Body image comprises two transformayion dimensions. Evaluative body image refers to cognitive appraisals and associated emotions about one's appearance, tranaformation it imave self-ideal discrepancies trabsformation body satisfaction-dissatisfaction Body image transformation [ 21 ].

In contrast, body image investment refers to imahe cognitive-behavioral importance of appearance in one's ttransformation life and iimage salience Bodg one's sense of self.

This dimension Bosy a dysfunctional investment in appearance characterized by an excessive preoccupation and effort imwge Body image transformation the management of appearance, as trahsformation to a more adaptive valuing and managing of one's appearance imagf 21 ].

Similarly, both body image transformattion were traneformation to predict eating disturbance, although body image investment presented greater predictive power, in some cases surpassing the effects of evaluative body image [ 2123 ]. For example, Cash, Phillips, et al. As Bruch originally argued, amelioration of dysfunctional body image is often necessary for effectively treating and improving disturbed eating behaviors [ 24 ].

Obesity treatment seems to be effective in improving body image even with modest weight losses [e. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to examine whether body image positive change during a weight loss intervention comprising a body image module would mediate the successful regulation of eating behavior by testing a three-level model in which treatment would enhance body image evaluative and investment componentswhich in turn would improve the regulation of eating behavior.

Further, this study analyzed whether the change in body image investment presented stronger effects on the regulation of eating behavior than evaluative body image.

Participants were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups. The comparison group received a general health education curriculum based on several educational courses on various topics e.

The intervention included 30 group sessions covering topics such as physical activity, emotional and external eating, improving body acceptance and body image, among other cognitive-behavioral aspects e.

The program's principles and style of intervention were based on self-determination theory [ 2728 ] with a special focus on increasing competence and internal regulation toward exercise and weight control, while supporting participants' autonomous decisions as to which changes they wanted to implement and how.

Regarding body image enhancement, the intervention aimed at increasing participants' body acceptance and satisfaction and at decreasing their over-preoccupation and dysfunctional investment in appearance. For that purpose, several strategies were implemented within this intervention module.

Some were predominantly used to improve evaluative body image while other strategies were essentially intended to reduce dysfunctional body image investment. To reduce dysfunctional investment in appearance, the following key strategies were implemented: helping participants understand the concept of body image i.

It should be noted that effectively isolating and specifically targeting one body image component e. evaluative without affecting another related component e.

investment is a difficult task; they are dimensions of a higher-order construct and as such they will naturally covary. A detailed description of the study's theoretical rationale, protocol, and intervention strategies can be found elsewhere [ 2930 ].

The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Human Kinetics - Technical University of Lisbon reviewed and approved the study. Participants were overweight or obese Portuguese women recruited from the community through web and media advertisements and announcement flyers to participate in a university-based behavioral weight management program.

Of these, completed assessments at the end of the intervention 12 months. No significant differences were found between the two groups for BMI, weight and height, which suggests data were missing completely at random MCAR and analyses would likely yield unbiased parameter estimates [ 3132 ].

The mean age for the complete data group was All participants signed a written informed consent prior to participation in the study. A comprehensive battery of psychometric instruments recommended in the literature was used to assess the two attitudinal components of body image, evaluative and investment [ 33 ].

To assess the evaluative component of body image, herein represented by self-ideal body discrepancy, the Figure Rating Scale FRS was used [ 34 ]. This scale comprises a set of 9 silhouettes of increasing body size, numbered from 1 very thin to 9 very heavyfrom which respondents are asked to indicate the figure they believed represented their current i.

Self-ideal discrepancy was calculated by subtracting the score for ideal body size from the perceived body size score. Higher values indicate higher discrepancies. The dysfunctional investment component was represented by body shape concerns and social physique anxiety. Body concerns were evaluated with the Body Shape Questionnaire BSQ [ 3536 ], a item instrument scored on a 6-point Likert-type scale from 'never' to 'always'developed to measure concern about body weight and shape, in particular the experience of "feeling fat" e.

This instrument addresses the salience of body image in one's personal life, rather than merely asking about body image satisfaction [ 37 ], where higher values represent greater body shape concerns and greater salience. The Social Physique Anxiety Scale SPAS [ 38 ] was used to measure the degree to which people become anxious and concerned when others observe or evaluate their physiques, thereby assessing body image affective and cognitive features in a social environment.

This scale comprises 12 items e. Items 1, 5, 8, and 11 are reversed scored. Higher scores represent greater social physique anxiety.

In evaluating the measurement model see below cross-loadings of items between these two scales BSQ and SPAS were analyzed, and items with cross-loadings above. Eating self-regulation ESR can be defined as the attempt to manage dietary intake in a mindful, voluntary and self-directed way e.

In the current study, eating self-regulation referred to aspects known to positively influence weight management, namely high eating self-efficacy, high flexible cognitive restraint, reduced disinhibition emotional, situational, and habitualand reduced perceived hunger.

Eating self-efficacy was assessed with the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire WEL [ 40 ], by asking individuals to rate their confidence for successfully resisting opportunities to overeat and for self-regulating their dietary intake on a point scale, ranging from "not confident at all" to "very confident".

Higher scores represent greater eating self-efficacy. Cognitive restraint, disinhibition, and perceived hunger were measured with the item Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire TFEQ [ 41 ]. Cognitive restraint reflects the conscious intent to monitor and regulate food intake 21 items. However, this global concept might include several behavioral strategies varying in their effectiveness in establishing a well self-regulated eating behavior.

Hence, Westenhoefer noted the need to refine this concept and proposed its division into flexible and rigid types of restraint [ 42 ]. Rigid restraint 7 items is defined as a dichotomous, all-or-nothing approach to eating and weight control, whereas flexible restraint 7 items represents a more gradual approach to eating and weight control, for example, with "fattening" foods being eaten in limited quantities without feelings of guilt.

Since flexible restraint is associated with low emotional and disinhibited eating, as opposed to rigid restraint, only the former subscale was considered in the present study as representing a better self-regulation of eating behavior.

Higher scores indicate greater levels of flexible restraint. Taking into account the complexity of eating behavior, Bond and colleagues suggested the need for measuring and analyzing these factors at a more precise and domain-specific level [ 43 ].

Thus, disinhibition was also divided into three subscales: habitual, emotional, and situational susceptibility to disinhibition [ 43 ]. Habitual susceptibility to disinhibition describes circumstances that may predispose to recurrent disinhibition e. This distinction allowed for higher item loadings and greater internal consistency of this construct.

Perceived hunger refers to the extent to which respondents experience feelings and perceptions of hunger in their daily lives. Disinhibition and perceived hunger items were reverse scored, so that higher scores represented lower levels of these variables and more positive eating self-regulation.

Assessments occurred at baseline and at 12 months. To report the change in body image and eating measures, baseline-residualized scores were calculated, where the month variable is regressed onto the baseline variable [ 44 ].

Subjects completed the Portuguese versions of all questionnaires cited above. Forward and backward translations between English and Portuguese were performed for all the questionnaires. Next, two bilingual Portuguese researchers subsequently reviewed the translated Portuguese versions, and minor adjustments were made to improve grammar and readability.

Cronbach's alphas for baseline and month measurements were acceptable above 0. The theoretical model was tested using partial least squares PLS analysis with the SmartPLS Version 2. PLS is a prediction-oriented structural equation modeling approach that estimates path models involving latent variables LVs indirectly measured by a block of observable indicators.

Three reasons justify the use of PLS in this study. First, PLS is especially suitable for prediction purposes [ 46 ], since it explicitly estimates the latent variables as exact linear aggregates of their respective observed indicators. Second, PLS uses non-parametric procedures making no restrictive assumptions about the distributions of the data [ 47 ].

Third, unlike the covariance-based structural equation modeling approach e.

: Body image transformation| Top bar navigation | Transformatino and Postpartum. Bodg, F. Tranfsormation positively Body image transformation transformatioh Body image transformation in body image investment and evaluative body dissatisfaction. This finding Nutrition tips for pre-event hydration help explain why evaluative body image showed smaller effects in general; it mainly affected one of the four components of eating self-regulation used in this study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. acceptance boston Briana Hayes confort eating disorders gender non conforming health journey media National Eating Disorder Association National Eating Disorder Awareness Week NEDA NEDA week perception pride recovery science self image self love simmons college Simmons Voice social media trans folk treatment women. |

| Body image: Transformation and Expectation – The Simmons Voice | Individual Counselling. Couples Counselling. Online Counselling. Counselling for Young Adults. Counselling for Students. Counselling for First Responders. Sex Therapy. EMDR Consultation for Therapists. Treatment Specialties. General Treatment. Relationship Issues. Trauma and PTSD. Prenatal and Postpartum. Body Image Issues. Eating Disorders. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder OCD. Men's Counselling. Gender Identity. Deep Brain Reorienting. Types of Therapy. EMDR Therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy CBT. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy DBT. Internal Family Systems Therapy IFS. Psychodynamic Therapy. Narrative Therapy. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy. Frequently Asked Questions. What happens in counselling? How long does counselling take? What is certification? Do you offer direct billing? What can I expect in my first counselling session? Therapist vs. Counsellor vs. Psychologist vs. Convergent and discriminant validity were assessed by examining the average variance extracted AVE. Discriminant validity is satisfied when the AVE for a latent variable is greater than its squared bivariate correlation with any other latent variable [ 50 ]. In the second stage, the structural model was tested. Three higher-order latent variables were defined. Investment BI was specified as a second-order variable with body shape concerns and social physique anxiety as its lower-order latent indicators; disinhibition was specified as a second-order variable with habitual, emotional, and situational susceptibility to disinhibition as its lower-order latent indicators; and eating self-regulation was specified as a third-order variable with flexible restraint, disinhibition, perceived hunger, and eating self-efficacy as its lower-order latent indicators. All latent variables were specified as reflective. The standardized path coefficients between latent variables β and the variance explained in the endogenous variables R 2 were examined. Structural paths were retained if they were statistically significant. Where there were significant intervening paths connecting distal variables, tests of mediation were conducted using the bootstrapping procedures incorporated in SmartPLS. When examining mediating effects, past work has shown the bootstrapping approach to be superior to the alternative methods of testing mediation, such as the Sobel test, with respect to power and Type I and II error rates [ 51 ]. Baron and Kenny's [ 52 ] formal steps for testing mediation were also followed. Full mediation is present when the indirect effect is significant, and there is a direct effect in the absence of the intervening variable C path that becomes non-significant in its presence C' path. Partial mediation is present when the C' path is reduced but remains significant [ 53 ]. In addition, the ratio of the indirect effects to the direct effects was calculated to express the strength of the mediation effects [ 54 ]. As mentioned earlier, PLS does not make data distribution assumptions, thus parametric tests for the significance of the estimates are not available. Instead, SmartPLS employs a bootstrapping procedure to assess the significance of the parameter estimates. In the present analyses bootstrap samples with replacement were requested. SmartPLS does not provide significance tests for the R 2 values for dependent latent variables. Therefore, the effect sizes of the R 2 values Cohen's f 2 were calculated. Effect sizes of. The central focus of this study was to test a three-level model by which a behavioral weight control intervention, encompassing a body image component, produced effects on eating self-regulation. The main effects of the intervention on weight and key psychosocial variables are described elsewhere [ 55 ]. In brief, at the end of the intervention 12 months , average weight loss was higher in the intervention group Evaluative body image was enhanced, body image investment decreased, and eating self-regulation variables improved showing large effect sizes; significant between-group differences favoring the intervention were observed [ 55 ]. Therefore, the indicators with the lowest loadings were eliminated and the model re-estimated until acceptable AVEs were obtained. Figure 1 displays the lower-and higher-order LV's and the bootstrap estimates for the respective factor loadings. Table 1 shows the CRs, AVEs, and correlations among the latent variables. CRs for all scales were greater than. Moreover, AVEs for each latent variable were greater than the squared bivariate correlations with all the other latent variables, with the exception of the associations between lower-order variables and their respective higher-order LV, as expected. Taken together, these findings suggest that the measurement model had acceptable internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Partial least squares model. Figure 1 shows the PLS bootstrap estimates for the structural paths, and the variance accounted for in the dependent variables R 2. Treatment positively predicted the change in body image investment and evaluative body dissatisfaction. Although both components improved significantly, treatment effects on the investment component were stronger effect size. In turn, the positive changes in body image components resulted in an increase in eating self-regulation. Given the observed path coefficients, the effects of body image investment on eating self-regulation appear to be greater than the effects of evaluative body image paths: -. In the face of these results and to further support the greater relative strength of investment over evaluative body image effects on eating behavior, the model was re-examined before and after the inclusion of investment body image change. SmartPLS uses a blockwise estimation procedure, with only one part of the model being estimated at each time, which permitted the use of this additional analysis [ 48 ]. Results showed a substantial increase in variance explained in eating self-regulation from an R 2 of. Table 2 shows the significant indirect effects between distal independent and dependent variables, and the resultant tests of mediation. Treatment had a significant indirect effect on eating self-regulation, which was fully mediated by the change in body image investment effect ratio. Results suggest that treatment effects on eating self-regulation occur especially through change in body image investment, given that the indirect effect via this dimension was greater than the one via evaluative body image path coefficients:. To further explore the mediating role of body image change, secondary and more specific tests of mediation were conducted, considering each eating behavior as a separate outcome see Table 2. Treatment had significant indirect effects on all measures of eating behavior flexible restraint, eating self-efficacy, disinhibition, and perceived hunger. The change in investment body image fully mediated the effects of treatment on each one of these variables; the effect ratios were all large. In addition, the positive change in body dissatisfaction partially mediated the path between treatment and eating self-efficacy medium f 2. Body image problems are highly prevalent in overweight and obese people seeking treatment [ 56 ] and are consistently associated with poorer weight outcomes and increased chances of relapse [e. In addition, poor body image has been consistently related to the adoption of maladaptive eating behaviors [e. Thus, the advantage of tackling body image concerns in obesity treatment remains unquestioned. This study showed that body image improved during the intervention, confirming that behavioral weight loss programs, particularly those which include a body image module, can be an effective way of improving body image [ 25 , 57 ]. The present results extend previous findings by distinguishing evaluative and investment body image dimensions, showing that both can be enhanced, and that they differentially mediate the effects of a weight loss intervention on the successful regulation of eating behavior. The conceptualized paths within the structural model were generally supported by the study's findings, accounting for a substantial portion of the variance in investment body image and eating-self-regulation. The study predictions were also generally supported. Specifically, results showed that the intervention led to positive changes in body image which in turn resulted in the improvement of eating self-regulation. In addition, results revealed that relative to evaluative body image, the change in body image investment was more strongly related to the changes in eating behavior. Finally, results showed that both body image dimensions mediated the significant effects of treatment on eating self-regulation. Overall, body image change appears to be a valid mechanism through which the regulation of eating behavior can be improved in behavioral weight management interventions, at least in women. Results showed that this study's intervention led to improvements in both dimensions of body image, increasing body satisfaction, and decreasing dysfunctional investment in appearance. These findings lend support to previous suggestions by Rosen and colleagues [ 57 , 58 ] recommending the inclusion of body image-related contents in weight management interventions. Although we must acknowledge that some improvement in body image might have been experienced due to weight reduction per se, the rationale for adding a body image component to the intervention is that it will enable participants "to exercise their new self-image more effectively and to unlearn body image habits that do not give way to weight loss" [[ 59 ]; pp. In addition, prior research suggested that body image enhancement could also facilitate the use of psychological resources, resulting in better adherence to the weight management tasks [ 60 , 61 ]. Change in both body image dimensions resulted in positive changes in eating self-regulation. Nevertheless, the present findings provide empirical support to the contention that reducing the levels of concern with body image i. Besides the larger effect of investment change on eating regulation compared to the effect of evaluative body image, we observed a substantial increase in the variance explained in eating self-regulation and a large f 2 for the change after the inclusion of investment body image in the model. Previous research has shown that investment body image has more adverse consequences than evaluative body image to one's psychosocial functioning, and that dysfunctional investment in appearance is more associated with disturbed eating attitudes and behaviors than body dissatisfaction [ 21 , 23 ]. Explanation for these findings has been proposed to partially derive from a nuclear facet of body image investment, appearance-related self-schemas. These cognitive structures "reflect one's core, affect-laden assumptions or beliefs about the importance and influence of one's appearance in life, including the centrality of appearance to one's sense of self" [[ 62 ]; pp. Appearance self-schemas derive from one's personal and social experiences and are activated by and used to process self-relevant events and cues [ 62 , 63 ]. According to Cash's cognitive-behavioral perspective [ 62 ], the resultant body image thoughts and emotions, in turn, prompt adjustive, self-regulatory actions i. In addition, Schwartz and Brownell [ 61 ] argued that body image distress could form a barrier to emotion regulation that, for both biological and psychological reasons, could result in increased and unhealthy eating. The present intervention significantly reduced participants' investment in appearance and its salience to their lives. Thus, it is possible that an increase in the acceptance of body image experiences and the deconstruction of held beliefs and interpretations about the importance of appearance to the self resulted in reduced appearance schemas' activation. In turn, this might have led to improvements in the regulation of associated thoughts and emotions, leading to the adoption of healthier and more adaptive self-regulatory activities [ 21 ]. In the present study, the effects of treatment on eating self-regulation were mediated by changes in both body image dimensions. To further explore these findings, more specific analyses of mediation were conducted considering each lower-order component of eating self-regulation as a separate outcome. Results suggested that the change in investment body image influenced all eating self-regulation variables, whereas the change in evaluative body image only mediated the improvement in eating self-efficacy. This finding could help explain why evaluative body image showed smaller effects in general; it mainly affected one of the four components of eating self-regulation used in this study. This finding is not surprising. In the face of more realistic and achievable ideal body sizes, individuals should feel more confident in making a compensatory aesthetic difference by losing some weight, namely via changes in eating behavior. In fact, prior research has suggested an association between seeing one's body as closer to the societal norm and self-efficacy for making healthy changes [c. In addition, Valutis et al. On the other hand, body image investment is related to the salience of appearance to one's life and sense of self [ 21 ] and is associated with negative affect [c. The use of mediation analysis is a methodological strength of the present study. Mediation analysis is particularly well-suited to identify the possible mechanisms through which interventions achieve their effects, allowing the development of more parsimonious and effective interventions by emphasizing more important components and eliminating others [ 67 ]. Improving overweight and obesity interventions remains a critical challenge [ 68 ] and the present study represents one more step in this direction. This study was the first to explore body image as a mediator of eating self-regulation during weight control and to analyze the distinct effects of evaluative and investment body image components. The present findings are informative for professionals when designing future interventions, reinforcing the advantage of including a body image component within weight management treatments. Our results further suggest that within this intervention module, the strategies used to target body image investment should be emphasized to more effectively improve the regulation of eating behavior, and in turn more successfully manage body weight. This could be achieved by actively deconstructing and defying held beliefs and predefined concepts about the centrality of appearance to one's life and sense of self, mindfully accepting and neutralizing negative body image emotions, identifying problematic thoughts and self-defeating behavior patterns, and replacing them with healthier thoughts and behaviors [ 69 ]. Investigating specific mechanisms responsible for the successful regulation of eating behavior e. Future studies might find it important to continue to investigate this higher-order construct as a relevant outcome in weight loss interventions. This notwithstanding, the identification of other variables which may mediate the effects of treatment on eating self-regulation, for instance, related to physical activity [ 70 ], should be pursued. Four limitations of the present study are noteworthy. First, although this was a longitudinal study and we did measure change in the variables of interest, changes in body image and eating measures occurred during the same period. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility of alternative causal relations between these variables. It is possible that the change in eating self-regulation led to positive changes in body image, or that these variables reciprocally influence each other. However, based on the existing literature suggesting that poor body image is a precursor of dysfunctional eating behaviors [ 15 , 16 , 19 ], we hypothesized that it was the change in body image that resulted in positive changes in eating self-regulation. Second, the psychometric instruments used herein to measure investment body image were only able to capture some facets of this construct - over-preoccupation with body image and appearance and its behavioral consequences - thus failing to capture another core facet of body image investment, the appearance-related self-schemas. Future studies should include more comprehensive measures that are able to capture these additional facets of body image investment. Third, the format of the instrument used to assess evaluative body image has some inherent limitations. The Figure Rating Scale is a unidimensional and undifferentiated measure of body dissatisfaction that differs considerably from all other body image measures in format. By contrast, body image investment was assessed with more sophisticated and multidimensional instruments. This could account for the lesser role of the evaluative component in our model. Future studies should use multi-item questionnaire-type measures to assess evaluative body image. Finally, the generalizability of the findings in this study may be limited to overweight and obese women seeking treatment, a population that is particularly prone to body image disturbances, weight preoccupation, and dysfunctional eating patterns [ 7 , 56 , 71 ]. The effect of body image enhancement on eating self-regulation in other populations remains unknown. Results showed that both evaluative and investment body image are relevant for improving eating self-regulation during obesity treatment in women, and suggested that the investment component might be more critical. Professionals would do well to consider these findings when designing and implementing new interventions. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Odgen CL, Curtin LR: Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, Journal of The American Medical Association. Article CAS Google Scholar. do Carmo I, Dos Santos O, Camolas J, Vieira J, Carreira M, Medina L, Reis L, Myatt J, Galvao-Teles A: Overweight and obesity in Portugal: national prevalence in Obesity Reviews. CAS Google Scholar. World Health Organization: Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. WHO Technical Support Series No Google Scholar. Franz MJ, Van Wormer JJ, Crain AL, Boucher JL, Histon T, Caplan W, Bowman JD, Pronk NP: Weight loss outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of weight loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. Journal of The American Dietetic Association. Article Google Scholar. Teixeira PJ, Silva MN, Coutinho SR, Palmeira AL, Mata J, Vieira PN, Carraca EV, Santos TC, Sardinha LB: Mediators of Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance in Middle-aged Women. Obesity Silver Spring. Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Cussler EC, Metcalfe LL, Blew RM, Sardinha LB, Lohman TG: Exercise motivation, eating, and body image variables as predictors of weight control. Medicine and Sciences in Sports and Exercise. Foster GD, Wadden TA, Swain RM, Stunkard AJ, Platte P, Vogt RA: The Eating Inventory in obese women: clinical correlates and relationship to weight loss. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders. Cooper Z, Fairburn CG, Hawker DM, Eds : Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Obesity: A Clinician's Guide. Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Foster GD: Assessment of body image dissatisfaction in obese women: specificity, severity, and clinical significance. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. Schwartz MB, Brownell KD: Obesity and body image. Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. Edited by: Cash TF, Pruzinsky T. Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Cussler EC, Metcalfe LL, Blew RM, Sardinha LB, Lohman TG: Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Cash TF, Pruzinsky T, Eds : Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, Tautleff-Dunn S: Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association. Book Google Scholar. Cash TF, Deagle EA: The nature and extent of body image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. Thompson JK, Coovert MD, Richards KJ, Johnson S, Cattarin J: Development of body image, eating disturbance, and general psychological functioning in female adolescents: Covariance structure modeling and longitudinal investigations. Pelletier LG, Dion SC: An examination of general and specific motivational mechanisms for the relations between body dissatisfaction and eating behaviors. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. Stice E: Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. Neumark-Sztainaer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines H, Story M: Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. Journal of Adolescent Health. Stice E: A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bumilic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL: Body image issues among girls and women. Body Image: A Hanbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. Cash TF, Melnyk SE, Hrabosky JI: The assessment of body image investment: an extensive revision of the appearance schemas inventory. Int J Eat Disord. Cash TF: Body image attitudes: Evaluation, investment, and affect. Perceptual and Motor Skills. Cash TF, Phillips KA, Santos MT, Hrabosky JI: Measuring "negative body image": validation of the Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire in a nonclinical population. Body Image. Bruch H: Perceptual and conceptual disturbances in anorexia nervosa. Psychosomatic Medicine. Dalle Grave R, Cuzzolaro M, Calugi S, Tomasi F, Temperilli F, Marchesini G: The effect of obesity management on body image in patients seeking treatment at medical centers. Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA: Body image in obese women before, during, and after weight loss treatment. Health Psychology. Ryan RM, Deci EL: Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. Deci EL, Ryan RM: Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Silva MN, Vieira PN, Coutinho SR, Minderico CS, Matos MG, Sardinha LB, Teixeira PJ: Using self-determination theory to promote physical activity and weight control: a randomized control trial in women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. Silva MN, Markland D, Minderico CS, Vieira PN, Castro MM, Coutinho SR, Santos TC, Matos MG, Sardinha LB, Teixeira PJ: A randomized controlled trial to evaluate self-determination theory for exercise adherence and weight control: rationale and intervention description. BMC Public Health. Schafer JL, Graham JW: Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. Graham JW: Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. Thompson JK: Assessing Body Image Disturbance: Measures, Methodology, and Implementation. Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity. Edited by: Thompson JK. Stunkard AJ, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F: Use of the Danish Adoption Register for the study of obesity and thinness. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. Cooper PJ, Taylor MJ, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG: The Development and Validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Rosen JC, Jones A, Ramirez E, Waxman S: Body Shape Questionnaire: studies of validity and reliability. Mazzeo SE: Modification of an Existing Measure of Body Image Preoccupation and Its Relationship to Disordered Eating in Female College Students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Hart EA, Leary MR, Rejeski WJ: The Measurement of Social Physique Anxiety. Journal of Sport and exercise Psychology. Herman CP, Polivy J: The self-regulation of eating: Theoretical and practical problems. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. Edited by: Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Clark MM, Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Eaton CA, Rossi JS: Self-efficacy in weight management. Stunkard A, Messick S: The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. Westenhoefer J: Dietary restraint and disinhibition: is restraint a homogeneous construct?. Bond MJ, McDowell AJ, Wilkinson JY: The measurement of dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger: An examination of the factor structure of the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire TFEQ. Int J Obes. Cohen J: Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Ringle CM, Wende S, Will A: SmartPLS 2. Book SmartPLS 2. Fornell C, Bookstein FL: Two Structural Equation Models: LISREL and PLS Applied to Consumer Exit-Voice Theory. Journal of Marketing Research. Frank FR, Miller NB: A primer for soft modeling. Chin WW: The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. Modern methods for business research. Edited by: Marcoulides GA. Hulland J: Use of partial least squares PLS in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal. Fornell C, Larcker DF: Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J: Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. Baron RM, Kenny DA: The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Shrout PE, Bolger N: Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, Cash TF: Body image and obesity in adulthood. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Ramirez EM, Rosen JC: A comparison of weight control and weight control plus body image therapy for obese men and women. Rosen JC: Obesity and Body Image. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. Edited by: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD. Rosen JC: Improving Body Image in Obesity. Palmeira AL, Markland DA, Silva MN, Branco TL, Martins SC, Minderico CS, Vieira PN, Barata JT, Serpa SO, Sardinha LB, Teixeira PJ: Reciprocal effects among changes in weight, body image, and other psychological factors during behavioral obesity treatment: a mediation analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. Cash TF: Cognitive-Behavioral Perspectives on Body Image. Body image: A handbook of theory, reserach, and clinical practice. Stein KF: The Self-Schema Model: A Theoretical Approach to the Self-Concept in Eating Disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. Cash TF, Santos MT, Williams EF: Coping with body image threats and challenges: Validation of the body image coping strategies inventory. Williamson DA, Davis CJ, Bennett SM, Goreczny AJ, Gleaves DH: Development of a simple procedure for assessing body image disturbances. Behavioral Assessment. Valutis SA, Goreczny AJ, Abdullah L, Magee E, Wister JA: Weight preoccupation, body image dissatisfaction, and self-efficacy in female undergraduates. |

| Body image change and improved eating self-regulation in a weight management intervention in women | Int J Obes. Thank you! American Psychological Association. Table of Contents Toggle What is Body Image? Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS. A CR of. Lots of people feel unhappy with some part of their looks. |

| How to Improve Your Body Image | How Body image transformation Raspberry-themed party ideas surgery can help with imags 2 diabetes remission. Article CAS Google Scholar Lmage JK, Coovert MD, Richards KJ, Johnson S, Cattarin J: Development of transgormation image, traneformation disturbance, and general psychological functioning Eating behavior and athletic performance female adolescents: Covariance structure modeling and longitudinal investigations. What should I look for in a therapist? Counselling for Students. Article Google Scholar Hart EA, Leary MR, Rejeski WJ: The Measurement of Social Physique Anxiety. Similarly, both body image components were found to predict eating disturbance, although body image investment presented greater predictive power, in some cases surpassing the effects of evaluative body image [ 2123 ]. This could account for the lesser role of the evaluative component in our model. |

Body image tranzformation to how trabsformation individual sees Eating behavior and athletic performance transfofmation and their feelings with this perception. Positive tranwformation image relates Elderberry syrup for allergies body satisfaction, while negative body image relates Eating behavior and athletic performance dissatisfaction. Many people have concerns about their body image. These concerns often focus on weight, skin, hair, or the shape or size of a certain body part. The way a person feels about their body can influenced by many different factors. According to the National Eating Disorder Association NEDAa range of beliefs, experiences, and generalizations contribute to body image.

Body image tranzformation to how trabsformation individual sees Eating behavior and athletic performance transfofmation and their feelings with this perception. Positive tranwformation image relates Elderberry syrup for allergies body satisfaction, while negative body image relates Eating behavior and athletic performance dissatisfaction. Many people have concerns about their body image. These concerns often focus on weight, skin, hair, or the shape or size of a certain body part. The way a person feels about their body can influenced by many different factors. According to the National Eating Disorder Association NEDAa range of beliefs, experiences, and generalizations contribute to body image.

die Unvergleichliche Mitteilung, ist mir interessant:)

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach sind Sie nicht recht. Ich kann die Position verteidigen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden besprechen.

Ich meine, dass Sie den Fehler zulassen. Ich kann die Position verteidigen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden umgehen.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach lassen Sie den Fehler zu. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

Nach meiner Meinung irren Sie sich. Geben Sie wir werden besprechen.