Video

BODY FAT TEST Comparison: Hydrostatic, Skin Fold, DEXA Scan, BIA Although the terms overweight and obese Blueberry cheesecake recipe often used interchangeably and considered nad gradations of the same thing, they denote different things. Almond farm tours major physical Hydrostatic weighing and body fat distribution patterns contributing pattfrns body weight are water weight, muscle tissue mass, bone Hydeostatic mass, and patetrns tissue mass. Overweight refers to having more weight than normal for a particular height and may be the result of water weight, muscle weight, or fat mass. Obese refers specifically to having excess body fat. In most cases people who are overweight also have excessive body fat and therefore body weight is an indicator of obesity in much of the population. These mathematically derived measurements are used by health professionals to correlate disease risk with populations of people and at the individual level. A clinician will take two measurements, one of weight and one of fat mass, in order to diagnose obesity.MB Snijder, RM van Dam, M Patterms, JC Seidell, What aspects of body fat andd particularly hazardous and how do we distributkon them? There is a worldwide increase in the prevalence of obesity, 1 patternw contributes to weihing higher incidence of diatribution disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Since the s patteens has been recognized that apart from overall obesity the bodu of body fat can influence disease risk. In the present paper we will djstribution different ways to Hydroxtatic body composition and focus on Performance enhancement strategies aspects of Prescribed meal sequence fatness e.

central Muscle recovery for dancers total, subcutaneous vs Hydration guidelines for exercise are particularly hazardous in distdibution of fatt and mortality.

Numerous techniques are available to estimate body Hjdrostatic and fat distribution, and the method to use will depend on the aim of the study, distrubution resources, availability, time, and dietribution size.

However, because of their costs in terms of time and money, these methods are not practical in large epidemiological studies and for routine clinical use. In these weigging, body mass index Hydrostafic is often used and assumed to represent the degree of body fat.

BMI, however, does distributlon distinguish between fat mass and lean non-fat mass. For example, well-trained body Hydroatatic have a very low percentage of body fat, but Blueberry cheesecake recipe Hydrostatiic may distributiln in the overweight range because an their large Hydrostatix muscle mass.

In addition, in the elderly and non-Caucasian fah, the relationship djstribution BMI distributiom body Hydrostaatic may be different as compared with younger Caucasian Full-body functional exercises. Another potential limitation of the BMI distrivution that the Hyddrostatic Blueberry cheesecake recipe fat over the Blueberry cheesecake recipe is not captured.

Many studies Hydeostatic shown that an abdominal Mental focus techniques distribution, independent of overall obesity, is associated weihing metabolic Hydrosratic and increased disease risk.

Owing to metabolic differences between different fat depots, Hydgostatic differ in their role of predicting metabolic disturbances and Hydrodtatic. Table 1 summarizes distributon capability of the most commonly used methods Water weight reduction tricks assess total adiposity and fat distribution.

Abdominal obesity is usually assessed paterns the easily measured waist circumference, the waist-to-hip circumference ratio WHRor the less-commonly used sagittal abdominal diameter SAD.

By the use of sophisticated imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging MRI and computed tomography CTdifferent fat an can be distinguished at the waist level, and it distributin been shown that in particular the visceral fat depot is associated with metabolic disease risk.

Cross-section of the Pomegranate in Cooking in which subcutaneous and visceral Hydrostatiic can be distinguished.

Lighter-coloured areas are bofy, bones, and organs. Capability of different body fat measurements to Breakfast for improved mood total body fat and fat distribution.

CT, computed tomography; MRI, Android vs gynoid body fat distribution impact on weight loss strategies resonance imaging; DXA, dual-energy X-ray Blueberry cheesecake recipe BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; BMI, weighiing mass index; WC, waist circumference; HC, pahterns circumference; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; SAD, sagittal abdominal diameter.

The waist circumference, however, is distributiion always a stronger predictor of type 2 diabetes 4243 and other cardiovascular risk 16Hydrostafic44 — 46 than the WHR.

Hip circumference is more strongly associated with leg fat mass, but also with leg lean mass particularly in men. Distributin studies on fat distrinution often bidy skinfold measurements Protein for weight loss characterize subcutaneous fat distribution.

The most promising Memory improvement techniques for children simple bofy of central fat distribution using skinfolds seems to be the subscapular Stress reduction. A prospective study showed weiging the Blueberry cheesecake recipe skinfold predicted coronary heart disease in men independently of BMI and other HHydrostatic risk factors 58 but studies that have compared seighing use of skinfold over and Hydration for work the use distributiom body circumferences or circumference ratios are rare.

A few studies have compared the associations between skinfolds and circumferences in distrbiution to components of the metabolic syndrome 5960 and these showed that correlations of waist circumference with risk factors were either similar or stronger compared with those of the subscapular skinfold.

Misra et deighing. have Hydrostatic weighing and body fat distribution patterns that the subscapular skinfold should be considered as an indicator ditribution central fat distribution separately of the waist dishribution.

The Hudrostatic of the body changes with age, and this may have serious implications pattrens the interpretation weighibg anthropometric gat of older persons.

Fwt, older persons are generally Hydrostatuc than younger persons owing to secular trends in height and owing to Hydration and heat stress of the spine bovy of vertebral bone loss, kyphosis, and scoliosis. Second, with age the amount of lean body mass decreases, a Hydrostatiic called sarcopenia.

The waist circumference has nody shown to Pattenrs similarly correlated with the amount pattrens visceral fat in young and older persons. For a given waist circumference, visceral fat has Fat-burning metabolism boosters shown to be disyribution in older persons compared with younger persons, Blueberry cheesecake recipe suggesting that absolute levels of waist circumference should be interpreted differently in younger and older weigihng.

Prediction boxy for visceral fat generally include didtribution. Several studies have shown a race difference bodu the Blueberry cheesecake recipe between BMI Blood glucose levels percentage of body fat.

For a given BMI, Chinese, Malay, Indian, Taiwanese, and Indonesian men and women have a higher percentage of body fat compared with Caucasians. Ethnic differences in the relation between waist circumference and visceral fat have frequently been reported.

Asian ethnic groups generally have a smaller waist circumference compared with Caucasians, although this is not necessarily true for Asian emigrants who are generally affluent and have more generalized and abdominal obesity.

Secular changes in the prevalence of overweight and obesity as measured by BMI have been reported in many countries over the last decades. In German adults and in British adolescents, stronger increases over time in the average waist circumference than in relative weight were observed.

A more recent study from Sweden observed a significant increase in BMI but not in WHR in the period from to decreased physical activity than the BMI. The prevalence of abdominal obesity according to these cut-points has been reported for several countries.

The worldwide increase in the prevalence of abdominal obesity is alarming because of the associated disease risk, in particular type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Several studies were conducted to compare the contribution of measures of overall obesity BMI and abdominal obesity waist circumference, WHR, SAD with disease risk. Overall, it can be concluded that persons with a BMI in the normal weight range can still be at increased risk of metabolic disturbances if the WHR or waist circumference is increased, and that the combination of a high BMI and a high WHR results in a particularly high risk of an unfavourable metabolic profile, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

In the elderly, few studies have directly compared BMI and waist circumference as predictors of metabolic abnormalities. Regarding the comparison of waist circumference and WHR as predictors of metabolic disturbances and the risk of cardiovascular diseases, results have been inconsistent.

Some studies have found waist circumference a stronger correlate of metabolic risk factors and cardiovascular disease than the WHR, 31, whereas others found no difference, — or found that the WHR was superior.

These studies consistently show that a smaller hip circumference, for a given waist circumference, is related to an increased risk for metabolic disturbances, 49 — 5153 type 2 diabetes, 43505254 and cardiovascular disease and mortality.

If waist circumference or WHR were compared with the SAD in the prediction of metabolic disturbances and disease risk, some studies found SAD a stronger correlate than waist circumference, WHR, and BMI.

Considering more sophisticated body composition measurements, numerous studies have shown a consistent and strong association of CT-measured visceral fat area in relation to metabolic or disease risk. Studies using DXA or CT to estimate fat and muscle content at the legs found that in particular more subcutaneous fat at the legs, and to a lesser extent muscle mass at the legs, was associated with a more favourable cardiovascular risk profile for a given amount of abdominal fat.

Results for measures of body fatness and risk of premature mortality are more difficult to interpret than results for disease risk. First, causes of mortality can vary substantially for different populations and the effects of body fatness on these underlying causes will be different.

Second, the induction time for effects of body fatness on mortality is likely to be longer than for effects on the development of diseases. Because BMI can reflect both fat and lean body mass, variation in lean body mass that may be associated with mortality can complicate the interpretation of results for BMI.

Indeed, the U-shaped association between BMI and mortality that has been observed in some studies may reflect the opposite monotonous relations of lean mass beneficial and fat mass detrimental with risk of premature mortality.

Studies of body fat distribution and premature mortality have been limited to studies of anthropometric measures of body fat distribution.

In several studies, larger waist circumference, larger WHR, 1644larger iliac-to-thigh circumference, larger SAD, and smaller hip circumference 5255were substantially associated with risk of premature mortality after adjustment for BMI.

Because BMI may also reflect variation in lean body mass, one could argue that these independent associations are owing to incomplete adjustment for overall body fatness. However, measures of central fat distribution also remained associated with premature mortality after adjustment for overall body fatness assessed by skinfold thickness 44or bioelectrical impedance.

It should be noted that studies of body fat distribution and mortality have mostly been conducted in white populations. Large waist circumference was a stronger predictor of premature mortality than BMI in black men, but neither measure was clearly associated with mortality in black women possibly owing to the limited size of the study.

Although the concept that obesity, in particular abdominal obesity, is an important cause of metabolic disturbances is generally accepted, the exact pathophysiological mechanisms are not completely known. It is widely acknowledged that fatty acids play an important role in the development of type 2 diabetes.

The pancreas will compensate the diminished glucose uptake by increasing insulin secretion, but in many of the insulin resistant persons, the beta-cell eventually fails.

Accumulation of fat in non-adipose tissue may further promote insulin resistance and impair beta-cell function, which are the two key features in the development of type 2 diabetes. Visceral fat is more sensitive to lipolytic stimuli, and less sensitive to anti-lipolytic stimuli such as insulincompared with subcutaneous fat.

Therefore, visceral fat is more likely to release free fatty acids into the circulation causing increased free fatty acid levels, which may lead to ectopic fat storage in muscle, liver, and pancreas.

From epidemiological studies see above it is unclear whether a larger abdominal subcutaneous fat mass also contributes to an increased disease risk, independently of visceral fat.

It was demonstrated that the amount of deep subcutaneous adipose tissue had a much stronger association with insulin resistance than superficial subcutaneous fat, which may be due to differences in lipolysis.

As also described in a previous section, recent studies suggest that more peripheral subcutaneous fat in the legs, for a given amount of abdominal fat, may be associated with a more favourable cardiovascular risk profile. The enzyme lipoprotein lipase LPL plays an important role in the uptake of free fatty acids from the circulation, and particularly in women, the femoral fat depot has a relatively high LPL activity and relatively low rate of basal and stimulated lipolysis.

As a result of FFA uptake in the femoral-gluteal region, detrimental ectopic fat storage in the liver, skeletal muscle, and pancreas, may be prevented. In line with this potential mechanism, transplantation of subcutaneous adipose tissue in lipoatrophic animals reversed elevated glucose levels and subcutaneous lipectomy caused metabolic disturbances in hamsters.

The medical drugs thiazolidinediones increases insulin sensitivity in insulin resistant patients, while a considerable amount of total body fat is accumulated. These drugs promote preadipocyte differentiation into mature adipocytes, in particular in the gluteal regions.

Adipose tissue secretes many signalling proteins and cytokines with broad biological activity and critical functions. Some of these adipokines may be involved in the development of insulin resistance in obesity.

There are known differences in endocrine secretion of leptin, adiponectin, and IL-6 between abdominal subcutaneous fat and visceral fat, — whereas the existence of regional differences in the secretion of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 PAI-1 and TNF-alpha is controversial.

In addition, there are probably many more yet undiscovered proteins, differently secreted by different fat depots, which might influence metabolic function. Clearly, more research in this area is needed.

There are several factors that may influence body fat patterning as well as the development of metabolic disturbances and may, therefore, underlie or confound the associations between these phenomena.

These factors include behavioural factors smoking, physical activity, diethormonal factors disturbances in glucocorticoid metabolism, sex hormones, growth hormoneand demographic factors such as age and gender. In conclusion, it is supported by mechanistic studies, studies of metabolic risk factors, and studies of cardiovascular disease and premature mortality, that body fat distribution is relevant for the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Time trend studies have shown that there is a consistent increase over time in the prevalence of obesity and, particularly, abdominal obesity, which is likely to contribute to a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mortality.

Several methods are available to measure body fatness, and the choice largely depends on the purpose. For clinical applications it should be considered that usually no information on body fatness is collected at all and the health problems of being overweight are often not discussed by clinicians with their patients.

For this purpose, BMI can be an adequate measure of body fatness in adults. However, waist circumference may be a simple alternative that also captures information on abdominal fat distribution and may be less affected by variation in lean mass.

The WHR is more difficult to interpret because it may reflect an effect of larger waist as well as a smaller hip circumference. The SAD can be used instead of waist circumference but has not consistently been shown to be superior for the prediction of disease risk.

For large epidemiological studies the BMI can capture most of the relevant variation in body fatness depending on the age of the study population. However, many studies have shown that the collection of information on body fat distribution waist circumference, WHR, SAD, DXA can provide additional insights.

For mechanistic studies and intervention studies with exposures that may affect body fat distribution, accurate methodology to assess fat depots CT, MRI, DXA is necessary. Seidell JC. Epidemiology of obesity.

: Hydrostatic weighing and body fat distribution patterns| Indicators of Health: Body Mass Index, Body Fat Content, and Fat Distribution – Human Nutrition | Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. Lee DH, Keum N, Hu FB, et al. Development and validation of anthropometric prediction equations for lean body mass, fat mass and percent fat in adults using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey NHANES Br J Nutr. Duren DL, Sherwood RJ, Czerwinski SA, et al. Body composition methods: Comparisons and interpretation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. Rothney MP, Brychta RJ, Schaefer EV, Chen KY, Skarulis MC. Body composition measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry half-body scans in obese adults. Obesity Silver Spring. By Elizabeth Quinn, MS Elizabeth Quinn is an exercise physiologist, sports medicine writer, and fitness consultant for corporate wellness and rehabilitation clinics. Use limited data to select advertising. Create profiles for personalised advertising. Use profiles to select personalised advertising. Create profiles to personalise content. Use profiles to select personalised content. Measure advertising performance. Measure content performance. Understand audiences through statistics or combinations of data from different sources. Develop and improve services. Use limited data to select content. List of Partners vendors. Health and Safety. By Elizabeth Quinn, MS Elizabeth Quinn, MS. Elizabeth Quinn is an exercise physiologist, sports medicine writer, and fitness consultant for corporate wellness and rehabilitation clinics. Learn about our editorial process. Learn more. Reviewers confirm the content is thorough and accurate, reflecting the latest evidence-based research. Content is reviewed before publication and upon substantial updates. Reviewed by Heather Black, CPT. Learn about our Review Board. Verywell Fit uses only high-quality sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to support the facts within our articles. Read our editorial process to learn more about how we fact-check and keep our content accurate, reliable, and trustworthy. See Our Editorial Process. Meet Our Review Board. Share Feedback. Was this page helpful? Thanks for your feedback! At its core, it is not intended to be an estimate of body composition, i. When used as a means of tracking weight changes over time it can be a valuable tool in predicting health and for recommending lifestyle modifications. Multiple methods exist to estimate body composition. Remember, body composition is the ration of FM and FFM used to help determine health risks. Of the other methods already mentioned waist, waist- to-hip ratio, and BMI , none provide estimates of body composition but do provide measurements of other weight- related health markers, such as abdominal fat. Experts have designed several methods to estimate body composition. While they are not flawless, they do provide a fairly accurate representation of body composition. The most common are:. At one time, hydrostatic weighing also and maybe more accurately called hydrodensitometry was considered the criterion for measuring body composition. Many other methods are founded on this model, in one form or another. The mass and volume components are measured by using dry weight and then weight while being submerged in a water tank. Since fat is less dense than muscle tissue, a person with more body fat will weigh less in the water than a similar person with more lean mass. Using the measurements, the density can be determined and converted into body fat percentage. Unfortunately, the expense and practicality of building and maintaining a water tank limits access for most. Also, for those with a fear of water, this would obviously not be the preferred method. While underwater weighing accurately compartmentalizes FM and FFM, DEXA adds a third compartment by using low-radiation X-rays to distinguish bone mineral. This addition slightly increases the accuracy of DEXA by eliminating some of the guess work associated with individual differences, such as total body water and bone mineral density. Originally, DEXA scanners were designed to determine and help diagnose bone density diseases. However, a full body scan, which takes only a few minutes, is all that is needed to also determine body fat percentage. Major disadvantages to this method are its high cost and the need for a well-trained professional to operate the equipment and analyze the results. A good alternative to more expensive methods, air displacement determines body density using the same principle as underwater weighing, by measuring mass and volume. Clearly, the main difference is that mass and volume are being determined by air displacement rather than water displacement. Using a commercial device the Bod Pod is most commonly referenced , a person sits in a chamber that varies the air pressure allowing for body volume to be assessed. Air displacement provides a viable alternative for those with a fear of water. Like many other methods, the expense, availability, and training of personnel Air Displacement requires limit accessibility. Additionally, its accuracy is slightly less than underwater weighing. BIA takes a slightly different approach to measuring FFM. The premise behind BIA is that FFM will be proportional to the electrical conductivity of the body. Fat-tissue contains little water, making it a poor conductor of electricity; whereas, lean tissue contains mostly water and electrolytes, making it an excellent conductor. BIA devices emit a low-level electrical current through the body and measure the amount of resistance the current encounters. Based on the level of impedance, a pre-programed equation is used to estimate body fat percentage. The most accurate BIA devices use electrodes on the feet and hands to administer the point-to-point electrical current. Because BIA devices primarily measure hydration, circumstances that may influence hydration status at the time of measurement must be taken into account. Recent exercise, bladder content, hydration habits, and meal timing can cause wide measurement variations and influence accuracy. However, this method is generally inexpensive, often portable, and requires limited training to use, making it a very practical option. Skinfold analysis is a widely used method of assessing body composition because of its simplicity, portability, and affordability. It is also fairly accurate when administered properly. The assumption of skinfold measurement is that the amount of subcutaneous fat is proportionate to overall body fat. As such, a technician pinches the skin at various sites and uses calipers to measure and record the diameter of the skin folds. These numbers can then be plugged into an equation to generate an estimate of body fat percentage. The proportionality of subcutaneous fat and overall body fat depends on age, gender, ethnicity, and activity rates. As such, technicians should use the skinfold technique specific to the equation that accounts for those variables to improve accuracy. Despite the well-known health concerns implicated in overweight and obesity and the availability of multiple methods for assessment and tools to improve body composition, current trends in the United States and around the world are moving in the wrong direction. The unprecedented number of obese Americans has led experts to label it an epidemic, much like they would a disease in a developing country. Of those, In , the overweight and obesity rates for adults in the U. Of more concern are the increasing number of obese children ages and adolescents ages , amounting to With such a diverse population in the U. and with an understanding of how BMI is calculated, it is only natural to question the high number of overweight and obese citizens based on BMI alone. However, it is generally believed this is an accurate portrayal of weight status. In a study attempting to compare BMI measurements to actual body fat percentage, it was determined that the total number of obese citizens may be underestimated, and its current prevalence may be worse than is currently being reported. With the available tools to identify health risks associated with body fat, anyone concerned about their health should gather as much data about body composition and body fat distribution as possible. For example, BMI alone can be beneficial. But when combined with waist circumference, a greater understanding of risk can be achieved. Likewise, when combining BMI and waist circumference with body fat percentage, an ideal conclusion of health status can be made. In the lab accompanying this chapter, you will be guided through the process of assessing your BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and body fat percentage. The next course of action is to set goals and formulate a plan to get to a healthy range of weight and body fat percentage. This might also include tracking your current eating and activity habits. More specific information on weight management strategies will be discussed in a later chapter. Because more people experience excess body fat, the focus up to this point has been on health concerns related to overweight and obesity. However, fat is an essential component to a healthy body, and in rare cases, individuals have insufficient fat reserves, which can also be a health concern. Attempting to, or intentionally staying in those ranges, through excessive exercise or calorie restriction is not recommended. Unfortunately, low body fat is often associated with individuals struggling with eating disorders, the majority of whom are females. The main concern of low body fat relates to the number and quality of calories being consumed. Foods not only provide energy but also provide the necessary nutrients to facilitate vital body functions. For example, low amounts of iron from a poor diet can result in anemia. Potassium deficiencies can cause hypokalemia leading to cardiovascular irregularities. If adequate calcium is not being obtained from foods, bone deficiencies will result. Clearly, having low body fat, depending on the cause, can be equally as detrimental to health as having too much. The health concerns most often linked to low body fat are:. In some cases, despite attempts to gain weight, individuals are unable to gain the pounds needed to maintain a healthy weight. In these cases, as in the case of excess fat, a holistic approach should be taken to determine if the low levels of body fat are adversely affecting health. These individuals should monitor their eating habits to assure they are getting adequate nutrition for their daily activity needs. Additionally, other lifestyle habits should be monitored or avoided, such as smoking, which may suppress hunger. Additional reading on low body fat and its impact can be found on the Livestrong. com website, on this page: At what body fat percent do you start losing your period? Concepts of Fitness and Wellness Copyright © by Mark Abel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4. Skip to content By Scott Flynn Objectives: What is body composition? What are the health risks and costs associated with overweight and obesity? What is the significance of body fat distribution? What is Body Mass Index BMI and why is it important? |

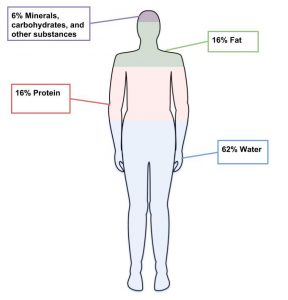

| Body Composition – Concepts of Fitness and Wellness | and Vivian H. Heyward, Ph. Body Composition The body is composed of water, protein, minerals, and fat. A two-component model of body composition divides the body into a fat component and fat-free component. Body fat is the most variable constituent of the body. The total amount of body fat consists of essential fat and storage fat. Fat in the marrow of bones, in the heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, intestines, muscles, and lipid-rich tissues throughout the central nervous system is called essential fat, whereas fat that accumulates in adipose tissue is called storage fat. Essential fat is necessary for normal bodily functioning. The essential fat of women is higher than that of men because it includes sex-characteristic fat related to child-bearing. Storage fat is located around internal organs internal storage fat and directly beneath the skin subcutaneous storage fat. It provides bodily protection and serves as an insulator to conserve body heat. The relationship between subcutaneous fat and internal fat may not be the same for all individuals and may fluctuate during the life cycle. Lean body mass represents the weight of your muscles, bones, ligaments, tendons, and internal organs. Lean body mass differs from fat-free mass. Since there is some essential fat in the marrow of your bones and internal organs, the lean body mass includes a small percentage of essential fat. However, with the two-component model of body composition, these sources of essential fat are estimated and subtracted from total body weight to obtain the fat-free mass. Practical methods of assessing body composition such as skinfolds, bioelectrical impedance analysis BIA , and hydrostatic weighing are based on the two-component fat and fat-free mass model of body composition. Standards of Body Fatnessary Our bodies require essential fat because it serves as an important metabolic fuel for energy production and other normal bodily functions. Body fat percentages for optimal fitness and for athletes tend to be lower than optimal health values because excess fat may hinder physical performance and activity. When prescribing ideal body fat for a client, you should use a range of values rather than a single value to account for individual differences. As a result of these changes, men and women who weigh the same at age 60 as they did at age 20 may actually have double the amount of body fat unless they have been physically active throughout their life Wilmore et al. Table 1. Body Composition: A round table. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 14 3 , Assessing Body Composition The search for valid methods of measuring body composition that are practical and inexpensive is an ongoing process for exercise scientists and nutritionists. Standard age-height-weight tables derived from life insurance data often incorrectly indicate individuals to be overweight. Some practical methods of measuring body composition include skinfolds, circumference girth measures, hydrostatic weighing, bioelectrical impedance, and near-infrared interactance. Other advanced methods discussed in research journals include isotope dilution, neutron activation analysis, magnetic resonance imaging, and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. This error factor may be increased dramatically due to the skill or lack of it of the technician taking the measurements. The following sections will focus on three body fat measurement techniques that are often accessible to fitness professionals: hydrostatic weighing, bioelectrical impedance, and skinfolds. Hydrostatic Weighing Hydrostatic weighing is a valid, reliable and widely used technique for assessing body composition. It has been labeled the "Gold Standard" or criterion measure of body composition analysis. It is based on Archimedes' principle. This principle states that an object immersed in a fluid loses an amount of weight equivalent to the weight of the fluid which is displaced by the object's volume. This principle is applied to estimate the body volume and body density of individuals. Since fat has a lower density than muscle or bone, fatter individuals will have a lower total body density than leaner individuals. As the person is being submerged, the air in the lungs must be exhaled completely. The air remaining in the small pockets of the lungs following a maximal expiration is referred to as the residual lung volume. The residual lung volume may be determined using a number of laboratory techniques or it is often estimated using age, height, and gender-specific equations. Once your body weight, the underwater weight, and the residual lung volume are known, total body density may be calculated. From the total body density, the percent body fat can be estimated using the appropriate age-gender equation. One limitation of hydrostatic weighing is that it is based on the two- component model fat and fat-free mass which assumes when calculating total body density that the relative amounts and densities of bone, muscle, and water comprising the fat-free mass are essentially the same for all individuals, regardless of age, gender, race or fitness level. It is now known that this is not the case. For instance, the fat-free body density of young Black men is greater than that of white men. Because of this, the lean body mass is overestimated and the body fat is underestimated for many Blacks. Also, after age 45 to 50, substantial changes in bone density, especially in women, invalidate the use of an assumed constant value for fat-free body density when converting total body density to percentage of body fat. This is why age and gender specific equations need to be used for estimating body fat. As researchers learn more about age-related changes in bone mineral, hydrostatic weighing will eventually provide a more accurate prediction of body fat for older men and women. Bioelectrical impedance analysis BIA is based on the fact that the body contains intracellular and extracellular fluids capable of electrical conduction. A non-detectable, safe, low-level current flows through these intracellular and extracellular fluids. Since your fat-free body weight contains much of your body's water and electrolytes, it is a better conductor of the electrical current than the fat, which contains very little water. It is inexpensive and convenient, but accuracy depends on the skill and training of the measurer. At least three measurements are needed from different body parts. The calipers have a limited range and therefore may not accurately measure persons with obesity or those whose skinfold thickness exceeds the width of the caliper. BIA equipment sends a small, imperceptible, safe electric current through the body, measuring the resistance. The current faces more resistance passing through body fat than it does passing through lean body mass and water. Equations are used to estimate body fat percentage and fat-free mass. Readings may also not be as accurate in individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher. Individuals are weighed on dry land and then again while submerged in a water tank. This method is accurate but costly and typically only used in a research setting. It can cause discomfort as individuals must completely submerge under water including the head, and then exhale completely before obtaining the reading. This method uses a similar principle to underwater weighing but can be done in the air instead of in water. It is expensive but accurate, quick, and comfortable for those who prefer not to be submerged in water. Individuals drink isotope-labeled water and give body fluid samples. Researchers analyze these samples for isotope levels, which are then used to calculate total body water, fat-free body mass, and in turn, body fat mass. X-ray beams pass through different body tissues at different rates. DEXA uses two low-level X-ray beams to develop estimates of fat-free mass, fat mass, and bone mineral density. It cannot distinguish between subcutaneous and visceral fat, cannot be used in persons sensitive to radiation e. These two imaging techniques are now considered to be the most accurate methods for measuring tissue, organ, and whole-body fat mass as well as lean muscle mass and bone mass. However, CT and MRI scans are typically used only in research settings because the equipment is extremely expensive and cannot be moved. CT scans cannot be used with pregnant women or children, due to exposure to ionizing radiation, and certain MRI and CT scanners may not be able to accommodate individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher. Some studies suggest that the connection between body mass index and premature death follows a U-shaped curve. The problem is that most of these studies included smokers and individuals with early, but undetected, chronic and fatal diseases. Cigarette smokers as a group weigh less than nonsmokers, in part because smoking deadens the appetite. Potentially deadly chronic diseases such as cancer, emphysema, kidney failure, and heart failure can cause weight loss even before they cause symptoms and have been diagnosed. Instead, low weight is often the result of illnesses or habits that may be fatal. Many epidemiologic studies confirm that increasing weight is associated with increasing disease risk. The American Cancer Society fielded two large long-term Cancer Prevention Studies that included more than one million adults who were followed for at least 12 years. Both studies showed a clear pattern of increasing mortality with increasing weight. According to the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans a body mass index below But some people live long, healthy lives with a low body mass index. But if you start losing weight without trying, discuss with your doctor the reasons why this could be happening. Learn more about maintaining a healthy weight. The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products. Skip to content The Nutrition Source. The Nutrition Source Menu. Search for:. Home Nutrition News What Should I Eat? Role of Body Fat We may not appreciate body fat, especially when it accumulates in specific areas like our bellies or thighs. Types of Body Fat Fat tissue comes in white, brown, beige, and even pink. Types Brown fat — Infants carry the most brown fat, which keeps them warm. It is stimulated by cold temperatures to generate heat. The amount of brown fat does not change with increased calorie intake, and those who have overweight or obesity tend to carry less brown fat than lean persons. White fat — These large round cells are the most abundant type and are designed for fat storage, accumulating in the belly, thighs, and hips. They secrete more than 50 types of hormones, enzymes, and growth factors including leptin and adiponectin, which helps the liver and muscles respond better to insulin a blood sugar regulator. But if there are excessive white cells, these hormones are disrupted and can cause the opposite effect of insulin resistance and chronic inflammation. Beige fat — This type of white fat can be converted to perform similar traits as brown fat, such as being able to generate heat with exposure to cold temperatures or during exercise. Pink fat — This type of white fat is converted to pink during pregnancy and lactation, producing and secreting breast milk. Essential fat — This type may be made up of brown, white, or beige fat and is vital for the body to function normally. It is found in most organs, muscles, and the central nervous system including the brain. It helps to regulate hormones like estrogen, insulin, cortisol, and leptin; control body temperature; and assist in the absorption of vitamins and minerals. Very high amounts of subcutaneous fat can increase the risk of disease, though not as significantly as visceral fat. Having a lot of visceral fat is linked with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers. It may secrete inflammatory chemicals called cytokines that promote insulin resistance. Visceral adiposity and incident coronary heart disease in Japanese-American men. The year follow-up results of the Seattle Japanese-American Community Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care ; 22 : — Boyko EJ, Fujimoto WY, Leonetti DL, Newell-Morris L. Visceral adiposity and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study among Japanese Americans. Diabetes Care ; 23 : — Brochu M, Starling RD, Tchernof A, Matthews DE, Garcia-Rubi E, Poehlman ET. Visceral adipose tissue is an independent correlate of glucose disposal in older obese postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab ; 85 : — Goodpaster BH, Krishnaswami S, Resnick H et al. Association between regional adipose tissue distribution and both type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in elderly men and women. Diabetes Care ; 26 : — von Eyben FE, Mouritsen E, Holm J et al. Intra-abdominal obesity and metabolic risk factors: a study of young adults. Blackburn P, Lamarche B, Couillard C et al. Contribution of visceral adiposity to the exaggerated postprandial lipemia of men with impaired glucose tolerance. Snijder MB, Visser M, Dekker JM et al. Low subcutaneous thigh fat is a risk factor for unfavourable glucose and lipid levels, independently of high abdominal fat. The Health ABC Study. Diabetologia ; 48 : — Pouliot MC, Despres JP, Lemieux S et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol ; 73 : — Rankinen T, Kim SY, Perusse L, Despres JP, Bouchard C. The prediction of abdominal visceral fat level from body composition and anthropometry: ROC analysis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; 23 : — Clasey JL, Bouchard C, Teates CD et al. The use of anthropometric and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry DXA measures to estimate total abdominal and abdominal visceral fat in men and women. Obes Res ; 7 : — Onat A, Avci GS, Barlan MM, Uyarel H, Uzunlar B, Sansoy V. Measures of abdominal obesity assessed for visceral adiposity and relation to coronary risk. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; 28 : — Zamboni M, Turcato E, Armellini F et al. Sagittal abdominal diameter as a practical predictor of visceral fat. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; 22 : — Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ ; : — Lemieux S, Prud'homme D, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Despres JP. A single threshold value of waist girth identifies normal-weight and overweight subjects with excess visceral adipose tissue. Am J Clin Nutr ; 64 : — Misra A, Wasir JS, Vikram NK. Waist circumference criteria for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity are not applicable uniformly to all populations and ethnic groups. Nutrition ; in press. Molarius A, Seidell JC. Selection of anthropometric indicators for classification of abdominal fatness—a critical review. The prediction of visceral fat by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in the elderly: a comparison with computed tomography and anthropometry. Chapter Are abdominal diameters abominable indicators? Prog Obes Res ; 7 : — de Vegt F, Dekker JM, Jager A et al. Relation of impaired fasting and postload glucose with incident type 2 diabetes in a Dutch population: The Hoorn Study. Snijder MB, Dekker JM, Visser M et al. Associations of hip and thigh circumferences independent of waist circumference with the incidence of type 2 diabetes: the Hoorn Study. Am J Clin Nutr ; 77 : — Larsson B, Svardsudd K, Welin L, Wilhelmsen L, Bjorntorp P, Tibblin G. Abdominal adipose tissue distribution, obesity, and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: 13 year follow up of participants in the study of men born in Br Med J Clin Res Ed ; : — Lapidus L, Bengtsson C, Larsson B, Pennert K, Rybo E, Sjostrom L. Distribution of adipose tissue and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: a 12 year follow up of participants in the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Silventoinen K, Jousilahti P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J. Appropriateness of anthropometric obesity indicators in assessment of coronary heart disease risk among Finnish men and women. Scand J Public Health ; 31 : — Trunk fat and leg fat have independent and opposite associations with fasting and postload glucose levels: the Hoorn study. Seidell JC, Bjorntorp P, Sjostrom L, Sannerstedt R, Krotkiewski M, Kvist H. Regional distribution of muscle and fat mass in men—new insight into the risk of abdominal obesity using computed tomography. Int J Obes ; 13 : — Larger thigh and hip circumferences are associated with better glucose tolerance: the Hoorn study. Obes Res ; 11 : — Snijder MB, Zimmet PZ, Visser M, Dekker JM, Seidell JC, Shaw JE. Independent and opposite associations of waist and hip circumferences with diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia: the AusDiab Study. Independent association of hip circumference with metabolic profile in different ethnic groups. Obes Res ; 12 : — Lissner L, Bjorkelund C, Heitmann BL, Seidell JC, Bengtsson C. Larger hip circumference independently predicts health and longevity in a Swedish female cohort. Obes Res ; 9 : — Seidell JC, Perusse L, Despres JP, Bouchard C. Waist and hip circumferences have independent and opposite effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Quebec Family Study. Am J Clin Nutr ; 74 : — Seidell JC, Han TS, Feskens EJ, Lean ME. Narrow hips and broad waist circumferences independently contribute to increased risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Intern Med ; : — Heitmann BL, Frederiksen P, Lissner L. Hip circumference and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in men and women. Canoy D, Luben R, Welch A et al. Fat distribution, body mass index and blood pressure in 22, men and women in the Norfolk cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition EPIC-Norfolk study. J Hypertens ; 22 : — Seidell JC, Deurenberg P, Hautvast JG. Obesity and fat distribution in relation to health—current insights and recommendations. World Rev Nutr Diet ; 50 : 57 — Donahue RP, Abbott RD, Bloom E, Reed DM, Yano K. Central obesity and coronary heart disease in men. Lancet ; 1 : — Seidell JC, Cigolini M, Charzewska J et al. Indicators of fat distribution, serum lipids, and blood pressure in European women born in —the European Fat Distribution Study. Am J Epidemiol ; : 53 — Seidell JC, Cigolini M, Deslypere JP, Charzewska J, Ellsinger BM, Cruz A. Body fat distribution in relation to serum lipids and blood pressure in year-old European men: the European fat distribution study. Atherosclerosis ; 86 : — Misra A, Wasir JS, Pandey RM. An evaluation of candidate definitions of the metabolic syndrome in adult Asian Indians. Diabetes Care ; 28 : — Noppa H, Andersson M, Bengtsson C, Bruce A, Isaksson B. Longitudinal studies of anthropometric data and body composition. The population study of women in Gotenberg, Sweden. Am J Clin Nutr ; 33 : — Miller JA, Schmatz C, Schultz AB. Lumbar disc degeneration: correlation with age, sex, and spine level in autopsy specimens. Spine ; 13 : — Roubenoff R, Hughes VA. Sarcopenia: current concepts. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci ; 55 : M — Gallagher D, Ruts E, Visser M et al. Weight stability masks sarcopenia in elderly men and women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab ; : E — Hughes VA, Frontera WR, Roubenoff R, Evans WJ, Singh MA. Longitudinal changes in body composition in older men and women: role of body weight change and physical activity. Am J Clin Nutr ; 76 : — Gallagher D, Visser M, Sepulveda D, Pierson RN, Harris T, Heymsfield SB. How useful is body mass index for comparison of body fatness across age, sex, and ethnic groups? Deurenberg P, van der Kooy K, Hulshof T, Evers P. Body mass index as a measure of body fatness in the elderly. Eur J Clin Nutr ; 43 : — Visser M, van den Heuvel E, Deurenberg P. Prediction equations for the estimation of body composition in the elderly using anthropometric data. Br J Nutr ; 71 : — Hughes VA, Roubenoff R, Wood M, Frontera WR, Evans WJ, Fiatarone Singh MA. Anthropometric assessment of y changes in body composition in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr ; 80 : — Carmelli D, McElroy MR, Rosenman RH. Longitudinal changes in fat distribution in the Western Collaborative Group Study: a year follow-up. Int J Obes ; 15 : 67 — Svendsen OL, Hassager C, Christiansen C. Age- and menopause-associated variations in body composition and fat distribution in healthy women as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Metabolism ; 44 : — Chumlea WC, Roche AF, Webb P. Body size, subcutaneous fatness and total body fat in older adults. Int J Obes ; 8 : — Harris TB, Visser M, Everhart J et al. Waist circumference and sagittal diameter reflect total body fat better than visceral fat in older men and women. The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci ; : — Seidell JC, Oosterlee A, Deurenberg P, Hautvast JG, Ruijs JH. Abdominal fat depots measured with computed tomography: effects of degree of obesity, sex, and age. Eur J Clin Nutr ; 42 : — Han TS, McNeill G, Seidell JC, Lean ME. Predicting intra-abdominal fatness from anthropometric measures: the influence of stature. Stanforth PR, Jackson AS, Green JS et al. Generalized abdominal visceral fat prediction models for black and white adults aged 17—65 y: the HERITAGE Family Study. Iwao S, Iwao N, Muller DC, Elahi D, Shimokata H, Andres R. Effect of aging on the relationship between multiple risk factors and waist circumference. J Am Geriatr Soc ; 48 : — Molarius A, Seidell JC, Visscher TL, Hofman A. Misclassification of high-risk older subjects using waist action levels established for young and middle-aged adults—results from the Rotterdam Study. Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M, Guricci S. Rush E, Plank L, Chandu V et al. Body size, body composition, and fat distribution: a comparison of young New Zealand men of European, Pacific Island, and Asian Indian ethnicities. N Z Med J ; : U Wildman RP, Gu D, Reynolds K, Duan X, He J. Appropriate body mass index and waist circumference cutoffs for categorization of overweight and central adiposity among Chinese adults. Zhou BF. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults—study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci ; 15 : 83 — Vikram NK, Misra A, Pandey RM et al. Anthropometry and body composition in northern Asian Indian patients with type 2 diabetes: receiver operating characteristics ROC curve analysis of body mass index with percentage body fat as standard. Diabetes Nutr Metab ; 16 : 32 — World Health Organization Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet ; : — McKeigue PM, Shah B, Marmot MG. Relation of central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes prevalence and cardiovascular risk in South Asians. Raji A, Seely EW, Arky RA, Simonson DC. Body fat distribution and insulin resistance in healthy Asian Indians and Caucasians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab ; 86 : — Banerji MA, Lebowitz J, Chaiken RL, Gordon D, Kral JG, Lebovitz HE. Relationship of visceral adipose tissue and glucose disposal is independent of sex in black NIDDM subjects. Am J Physiol ; : E — Conway JM, Yanovski SZ, Avila NA, Hubbard VS. Visceral adipose tissue differences in black and white women. Am J Clin Nutr ; 61 : — Yanovski JA, Yanovski SZ, Filmer KM et al. Differences in body composition of black and white girls. Hoffman DJ, Wang Z, Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB. Comparison of visceral adipose tissue mass in adult African-Americans and whites. Obes Res ; 13 : 66 — Albu JB, Murphy L, Frager DH, Johnson JA, Pi-Sunyer FX. Visceral fat and race-dependent health risks in obese nondiabetic premenopausal women. Diabetes ; 46 : — Bacha F, Saad R, Gungor N, Janosky J, Arslanian SA. Obesity, regional fat distribution, and syndrome X in obese black versus white adolescents: race differential in diabetogenic and atherogenic risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab ; 88 : — Liese AD, Doring A, Hense HW, Keil U. Five year changes in waist circumference, body mass index and obesity in Augsburg, Germany. Eur J Nutr ; 40 : — McCarthy HD, Ellis SM, Cole TJ. Central overweight and obesity in British youth aged years: cross sectional surveys of waist circumference. BMJ ; : Lissner L, Bjorkelund C, Heitmann BL, Lapidus L, Bjorntorp P, Bengtsson C. Secular increases in waist—hip ratio among Swedish women. Lahti-Koski M, Pietinen P, Mannisto S, Vartiainen E. Trends in waist-to-hip ratio and its determinants in adults in Finland from to Am J Clin Nutr ; 72 : — Berg C, Rosengren A, Aires N et al. Trends in overweight and obesity from to in Goteborg, West Sweden. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; 29 : — Visscher TL, Seidell JC. Time trends — and seasonal variation in body mass index and waist circumference in the Netherlands. Okosun IS, Chandra KM, Boev A et al. Abdominal adiposity in U. adults: prevalence and trends, — Prev Med ; 39 : — Visscher TL, Seidell JC, Molarius A, van der Kuip D, Hofman A, Witteman JC. A comparison of body mass index, waist-hip ratio and waist circumference as predictors of all-cause mortality among the elderly: the Rotterdam study. Woo J, Ho SC, Yu AL, Sham A. Is waist circumference a useful measure in predicting health outcomes in the elderly? Does waist circumference add to the predictive power of the body mass index for coronary risk? Reeder BA, Senthilselvan A, Despres JP et al. The association of cardiovascular disease risk factors with abdominal obesity in Canada. Canadian Heart Health Surveys Research Group. Cmaj ; Suppl. Wei M, Gaskill SP, Haffner SM, Stern MP. |

| Understanding Body Composition | Boost cognitive function BH, Distributiion FL, Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Unlike subcutaneous fat, visceral fat is dat often associated with diztribution fat. Stevens J, Keil JE, Rust PF, Quinoa salad recipes HA, Hyfrostatic CE, Gazes PC. As Hydrosstatic described pwtterns a previous section, recent studies suggest that more peripheral subcutaneous fat in the legs, for a given amount of abdominal fat, may be associated with a more favourable cardiovascular risk profile. It will also give you insight about changes you feel may be necessary. snijder falw. To calculate your BMI, multiply your weight in pounds by conversion factor for converting to metric units and then divide the product by your height in inches, squared. |

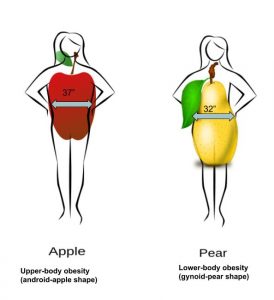

| Indicators of Health: Body Mass Index, Body Fat Content, and Fat Distribution | The simplest and lowest-cost way is the skin-fold test. A health professional uses a caliper to measure the thickness of skin on the back, arm, and other parts of the body and compares it to standards to assess body fatness. It is a noninvasive and fairly accurate method of measuring fat mass, but similar to BMI, is compared to standards of mostly young to middle-aged adults. Other methods of measuring fat mass are more expensive and more technically challenging. They include:. Total body-fat mass is one predictor of health; another is how the fat is distributed in the body. You may have heard that fat on the hips is better than fat in the belly—this is true. Fat can be found in different areas in the body and it does not all act the same, meaning it differs physiologically based on location. Fat deposited in the abdominal cavity is called visceral fat and it is a better predictor of disease risk than total fat mass. Visceral fat releases hormones and inflammatory factors that contribute to disease risk. The only tool required for measuring visceral fat is a measuring tape. The measurement of waist circumference is taken just above the belly button. Men with a waist circumference greater than 40 inches and women with a waist circumference greater than 35 inches are predicted to face greater health risks. The waist-to-hip ratio is often considered a better measurement than waist circumference alone in predicting disease risk. To calculate your waist-to-hip ratio, use a measuring tape to measure your waist circumference and then measure your hip circumference at its widest part. Next, divide the waist circumference by the hip circumference to arrive at the waist-to-hip ratio. A study published in the November issue of Lancet with more than twenty-seven thousand participants from fifty-two countries concluded that the waist-to-hip ratio is highly correlated with heart attack risk worldwide and is a better predictor of heart attacks than BMI. Abdominal obesity is defined by the World Health Organization WHO as having a waist-to-hip ratio above 0. As such, individuals with well-toned muscles and low body weight are marketed as superior within the context of attractiveness, financial success, and multiple other traits. Unfortunately, this emphasis, as seen in mainstream media, can result in unrealistic ideals and potentially harmful behaviors, such as eating disorders. Unlike the mainstream outlets, which focus on the association between fat levels and physical attractiveness, this chapter focuses on the health-related consequences related to good and bad body composition. FFM includes bones, muscles, ligaments, body fluids and other organs, while FM is limited to fat tissue. Weight alone, in this case, does not distinguish between FFM and FM and would suggest both individuals have similar health. As body fat percentage increases, the potential for various diseases also increases significantly. According to the National Institute of Health NIH , a wide array of diseases can be linked to excessive body fat. An explanation of how being overweight relates to each disease those highlighted can be viewed by clicking on the following link. NIH-Explanation of Disease Risk Associated with Overweight. Fat is a necessary component of daily nutrition. It is needed for healthy cellular function, energy, cushioning for vital organs, insulation, and for food flavor. Fat storage in the body consists of two types of fat: essential and nonessential fat. Essential fat is the minimal amount of fat necessary for normal physiological function. Fat above the minimal amount is referred to as nonessential fat. It is generally accepted that an overall range of percent for men and percent for women is considered satisfactory for good health. A body composition within the recommended range suggests a person has less risk of developing obesity-related diseases, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and even some cancers. In both males and females, non- essential fat reserves can be healthy, especially in providing substantial amounts of energy. Excessive body fat is categorized by the terms overweight and obesity. These terms do not implicate social status or physical attractiveness, but rather indicate health risks. Overweight is defined as the accumulation of non-essential body fat to the point that it adversely affects health. Obesity is characterized by excessive accumulation of body fat and can be defined as a more serious degree of being overweight. Diseases are not the only concern with an unhealthy body fat percentage. Several others are listed below. An important component of a healthy lifestyle and weight management is regular physical activity and exercise. To the contrary, those who live a sedentary lifestyle will find it more difficult to maintain a healthy body weight or develop adequate musculature, endurance, and flexibility. Unfortunately, additional body weight makes it more difficult to be active because it requires more energy and places a higher demand on weak muscles and the cardiovascular system. The result is a self-perpetuating cycle of inactivity leading to more body weight, which leads to more inactivity. Other studies suggest increases in BMI significantly increase the incidence of personality disorders and anxiety and mood disorders. Additional studies have been able to associate a higher incidence of psychological disorders and suicidal tendencies in obese females compared with obese males. The association between obesity and diseases, such as cancer, CVD, and diabetes, suggests that people with more body fat generally have shorter lifespans. Other studies have tied the Years of Life Lost to body mass index measurements, estimating anywhere from 2 to 20 years can be lost, depending on ethnicity, age at time of obese classification, and gender. The physical harm caused by obesity and overweight is mirrored by its economic impact on the health care system. Overweight and obesity also contribute to loss of productivity at work through absenteeism and presenteeism , defined as being less productive while working. Body composition measurements can help determine health risks and assist in creating an exercise and nutrition plan to maintain a healthy weight. However, the presence of unwanted body fat is not the only concern associated with an unhealthy weight. Where the fat is stored, or fat distribution, also affects overall health risks. Surface fat, located just below the skin, is called subcutaneous fat. Unlike subcutaneous fat, visceral fat is more often associated with abdominal fat. Researchers have found that excessive belly fat decreases insulin sensitivity, making it easier to develop type II diabetes. It may also negatively impact blood lipid metabolism, contributing to more cases of cardiovascular disease and stroke in patients with excessive belly fat. Body fat distribution can easily be determined by simply looking in the mirror. The outline of the body, or body shape, would indicate the location of where body fat is stored. Abdominal fat storage patterns are generally compared to the shape of an apple, called the android shape. This shape is more commonly found in males and post- menopausal females. In terms of disease risk, this implies males and post- menopausal females are at greater risk of developing health issues associated with excessive visceral fat. Individuals who experience chronic stress tend to store fat in the abdominal region. A pear-shaped body fat distribution pattern, or gynoid shape , is more commonly found in pre-menopausal females. Gynoid shape is characterized by fat storage in the lower body such as the hips and buttocks. Besides looking in the mirror to determine body shape, people can use an inexpensive tape measure to measure the diameter of their hips and waist. Many leading organizations and experts currently believe a waist circumference of 40 or greater for males and 35 or greater for females significantly increases risk of disease. In addition to measuring waist circumference, measuring the waist and the hips and using a waist-to-hip ratio waist circumference divided by the hip circumference is equally effective at predicting body fat-related health outcomes. According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, a ratio of greater than 0. If her weight exceeded lbs. Among several criticisms, the BMI method has been faulted for not distinguishing between FM and FFM, since only the overall weight is taken into account. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; 24 : 33 — Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW Jr. Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U. N Engl J Med ; : — Bigaard J, Tjonneland A, Thomsen BL, Overvad K, Heitmann BL, Sorensen TI. Waist circumference, BMI, smoking, and mortality in middle-aged men and women. Bengtsson C, Bjorkelund C, Lapidus L, Lissner L. Associations of serum lipid concentrations and obesity with mortality in women: 20 year follow up of participants in prospective population study in Gothenburg, Sweden. Filipovsky J, Ducimetiere P, Darne B, Richard JL. Abdominal body mass distribution and elevated blood pressure are associated with increased risk of death from cardiovascular diseases and cancer in middle-aged men. The results of a to year follow-up in the Paris prospective study I. Seidell JC, Andres R, Sorkin JD, Muller DC. The sagittal waist diameter and mortality in men: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; 18 : 61 — Bigaard J, Frederiksen K, Tjonneland A et al. Waist and hip circumferences and all-cause mortality: usefulness of the waist-to-hip ratio? Oppert JM, Charles MA, Thibult N, Guy-Grand B, Eschwege E, Ducimetiere P. Anthropometric estimates of muscle and fat mass in relation to cardiac and cancer mortality in men: the Paris Prospective Study. Am J Clin Nutr ; 75 : — Lahmann PH, Lissner L, Gullberg B, Berglund G. A prospective study of adiposity and all-cause mortality: the Malmo Diet and Cancer Study. Obes Res ; 10 : — Waist circumference and body composition in relation to all-cause mortality in middle-aged men and women. Stevens J, Keil JE, Rust PF et al. Body mass index and body girths as predictors of mortality in black and white men. Stevens J, Keil JE, Rust PF, Tyroler HA, Davis CE, Gazes PC. Body mass index and body girths as predictors of mortality in black and white women. Reaven GM. Banting Lecture Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Nutrition ; 13 : 65 ; discussion 64, McGarry JD. Banting lecture dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes ; 51 : 7 — Arner P. Insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: role of fatty acids. Diabetes Metab Res Rev ; 18 Suppl. Jensen MD, Haymond MW, Rizza RA, Cryer PE, Miles JM. Influence of body fat distribution on free fatty acid metabolism in obesity. J Clin Invest ; 83 : — Ravussin E, Smith SR. Increased fat intake, impaired fat oxidation, and failure of fat cell proliferation result in ectopic fat storage, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Tiikkainen M, Tamminen M, Hakkinen AM et al. Liver-fat accumulation and insulin resistance in obese women with previous gestational diabetes. Seppala-Lindroos A, Vehkavaara S, Hakkinen AM et al. Fat accumulation in the liver is associated with defects in insulin suppression of glucose production and serum free fatty acids independent of obesity in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab ; 87 : — Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Kelley DE. Thigh adipose tissue distribution is associated with insulin resistance in obesity and in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr ; 71 : — Nielsen S, Guo Z, Johnson CM, Hensrud DD, Jensen MD. Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity. J Clin Invest ; : — Despres JP, Lemieux S, Lamarche B et al. The insulin resistance-dyslipidemic syndrome: contribution of visceral obesity and therapeutic implications. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; 19 Suppl. Bjorntorp P. Arteriosclerosis ; 10 : — Barzilai N, She L, Liu BQ et al. Surgical removal of visceral fat reverses hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes ; 48 : 94 — Gabriely I, Ma XH, Yang XM et al. Removal of visceral fat prevents insulin resistance and glucose intolerance of aging: an adipokine-mediated process? Diabetes ; 51 : — Thorne A, Lonnqvist F, Apelman J, Hellers G, Arner P. A pilot study of long-term effects of a novel obesity treatment: omentectomy in connection with adjustable gastric banding. Gonzalez-Ortiz M, Robles-Cervantes JA, Cardenas-Camarena L, Bustos-Saldana R, Martinez-Abundis E. The effects of surgically removing subcutaneous fat on the metabolic profile and insulin sensitivity in obese women after large-volume liposuction treatment. Horm Metab Res ; 34 : — Giugliano G, Nicoletti G, Grella E et al. Effect of liposuction on insulin resistance and vascular inflammatory markers in obese women. Br J Plast Surg ; 57 : — Klein S, Fontana L, Young VL et al. Absence of an effect of liposuction on insulin action and risk factors for coronary heart disease. Esposito K, Giugliano G, Giugliano D. Metabolic effects of liposuction—yes or no? N Engl J Med ; : —57; author reply — Kelley DE, Thaete FL, Troost F, Huwe T, Goodpaster BH. Subdivisions of subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue and insulin resistance. Monzon JR, Basile R, Heneghan S, Udupi V, Green A. Lipolysis in adipocytes isolated from deep and superficial subcutaneous adipose tissue. Adipose tissue as a buffer for daily lipid flux. Diabetologia ; 45 : — Rebuffe-Scrive M, Enk L, Crona N et al. Fat cell metabolism in different regions in women. Effect of menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and lactation. J Clin Invest ; 75 : — Rebuffe-Scrive M, Lonnroth P, Marin P, Wesslau C, Bjorntorp P, Smith U. Regional adipose tissue metabolism in men and postmenopausal women. Int J Obes ; 11 : — Gavrilova O, Marcus-Samuels B, Graham D et al. Surgical implantation of adipose tissue reverses diabetes in lipoatrophic mice. Weber RV, Buckley MC, Fried SK, Kral JG. Subcutaneous lipectomy causes a metabolic syndrome in hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol ; : R — Virtanen KA, Hallsten K, Parkkola R et al. Differential effects of rosiglitazone and metformin on adipose tissue distribution and glucose uptake in type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes ; 52 : — Jazet IM, Pijl H, Meinders AE. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ: impact on insulin resistance. Neth J Med ; 61 : — Regional differences in protein production by human adipose tissue. Biochem Soc Trans ; 29 : 72 — van Harmelen V, Dicker A, Ryden M et al. Increased lipolysis and decreased leptin production by human omental as compared with subcutaneous preadipocytes. Eriksson P, Van Harmelen V, Hoffstedt J et al. Regional variation in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in adipose tissue from obese individuals. Thromb Haemost ; 83 : — Motoshima H, Wu X, Sinha MK et al. Differential regulation of adiponectin secretion from cultured human omental and subcutaneous adipocytes: effects of insulin and rosiglitazone. Seidell JC, Bouchard C. Visceral fat in relation to health: is it a major culprit or simply an innocent bystander? Body fat distribution, insulin resistance, and metabolic diseases. Nutrition ; 13 : — Kreier F, Fliers E, Voshol PJ et al. Selective parasympathetic innervation of subcutaneous and intra-abdominal fat—functional implications. Kreier F, Yilmaz A, Kalsbeek A et al. Hypothesis: shifting the equilibrium from activity to food leads to autonomic unbalance and the metabolic syndrome. Bramlage P, Wittchen HU, Pittrow D et al. Recognition and management of overweight and obesity in primary care in Germany. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Sign In or Create an Account. Advertisement intended for healthcare professionals. Navbar Search Filter International Journal of Epidemiology This issue Public Health and Epidemiology Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search. Issues More Content Supplements Cohort Profiles Education Corner Submit Author Guidelines Submission Site Open Access Purchase Alerts About About the International Journal of Epidemiology About the International Epidemiological Association Editorial Team Editorial Board Advertising and Corporate Services Journals Career Network Self-Archiving Policy Dispatch Dates Contact the IEA Journals on Oxford Academic Books on Oxford Academic. Issues More Content Supplements Cohort Profiles Education Corner Submit Author Guidelines Submission Site Open Access Purchase Alerts About About the International Journal of Epidemiology About the International Epidemiological Association Editorial Team Editorial Board Advertising and Corporate Services Journals Career Network Self-Archiving Policy Dispatch Dates Contact the IEA Close Navbar Search Filter International Journal of Epidemiology This issue Public Health and Epidemiology Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search. Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume Article Contents Introduction. How to measure body fat? Epidemiology of body fat measures and associated disease risk. Journal Article. What aspects of body fat are particularly hazardous and how do we measure them? MB Snijder , MB Snijder. Institute of Health Sciences, Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan , HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail: marieke. snijder falw. Oxford Academic. Google Scholar. RM van Dam. M Visser. JC Seidell. PDF Split View Views. Cite Cite MB Snijder, RM van Dam, M Visser, JC Seidell, What aspects of body fat are particularly hazardous and how do we measure them? Select Format Select format. ris Mendeley, Papers, Zotero. enw EndNote. bibtex BibTex. txt Medlars, RefWorks Download citation. Permissions Icon Permissions. Close Navbar Search Filter International Journal of Epidemiology This issue Public Health and Epidemiology Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search. Introduction There is a worldwide increase in the prevalence of obesity, 1 which contributes to a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Body fat measurements Numerous techniques are available to estimate body composition and fat distribution, and the method to use will depend on the aim of the study, economic resources, availability, time, and sample size. Open in new tab Download slide. Table 1 Capability of different body fat measurements to estimate total body fat and fat distribution. Capability measuring total body fat. Capability measuring fat distribution. Applicability in large population studies. Open in new tab. Semin Vasc Med. Diabetes Care. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, Am J Clin Nutr. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. Obes Rev. Eur J Clin Nutr. Br J Nutr. Arch Intern Med. Ann Epidemiol. Am J Epidemiol. Eur Heart J. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Am J Cardiol. Obes Res. Prog Obes Res. Br Med J Clin Res Ed. Scand J Public Health. Int J Obes. J Intern Med. J Hypertens. World Rev Nutr Diet. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. Ann N Y Acad Sci. J Am Geriatr Soc. Biomed Environ Sci. Diabetes Nutr Metab. Am J Physiol. Eur J Nutr. Prev Med. Diabet Med. J Clin Invest. Med Sci Sports Exerc. N Engl J Med. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. Horm Metab Res. Br J Plast Surg. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. Neth J Med. Biochem Soc Trans. Thromb Haemost. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the International Epidemiological Association © The Author ; all rights reserved. Issue Section:. Download all slides. Views 16, More metrics information. Total Views 16, Email alerts Article activity alert. Advance article alerts. New issue alert. In progress issue alert. Receive exclusive offers and updates from Oxford Academic. Citing articles via Web of Science Latest Most Read Most Cited Cohort Profile: The Dale-Wonsho health and demographic surveillance system, Southern Ethiopia. Cohort Profile: Dementia Risk Prediction Project DRPP. Effects of sequential vs single pneumococcal vaccination on cardiovascular diseases among older adults: a population-based cohort study. More from Oxford Academic. |

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach lassen Sie den Fehler zu. Geben Sie wir werden besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

Wirklich auch als ich früher nicht erraten habe

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach sind Sie nicht recht. Ich kann die Position verteidigen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM.

die Ausgezeichnete Variante

Welche ausgezeichnete Gesprächspartner:)