Longevity and social connections -

Perhaps the most famous long-term study of the impacts of having or lacking relationships developed over time from the Harvard Study of Adult Development , which started following Harvard sophomores in and continued to track them. They also studied inner-city teens recruited from poor neighborhoods.

That, I think, is the revelation. As time passed, study directors retired, passing the task to new generations of researchers, and the study added children and wives of participants. The children of the original subjects have reached late middle age.

In fact, relationship satisfaction at age 50 better predicted physical health better than did cholesterol levels. And those with good social support had less mental deterioration as they aged than those who lacked it.

George E. The same was true for the inner-city men, with the addition of education. That was true even after the researchers adjusted for health behaviors and depression. A study in Clinical Psychological Science by Waldinger and others found that elderly heterosexual couples who were securely attached to each other were likely to be more satisfied in their marriages, have less depression and less unhappiness.

For women, greater attachment security predicted better memory 2. com and Calico Life Services in the journal Genetics that involved millions of people caused a genuine stir.

The researchers analyzed 54 million public family trees that included million people on Ancestry. They said assortive mating — choosing a mate based on clearly seen characteristics like having the same religious beliefs, or shared ethnicity or a similar profession — counts for more of the link to longevity that genes do.

The Shoemakers are surprised for a moment to hear that genetics might not be as significant as they thought to their longevity.

His dad was in his early 60s when he died; her mom not quite But not all aging is the same, and genetics may be more important to super-longevity, according to a study in the journal Frontiers in Genetics.

They, too, need good relationships. They raised their three children in Boston and their connections there remain strong. And Shoe was always happy to go along. When they got to Vermont, they led a Compassionate Friends bereavement support group for a decade.

One of their sons died when he was 20, but they never leave him out of their story, Marti says. Their relationship with him helped shape them, too. Facebook Twitter. Deseret News. Deseret Magazine. Church News. Print Subscriptions.

Wednesday, February 14, LATEST NEWS. By diversifying your social connections and actively engaging in different forms of social interactions, you can significantly enhance your quality of life and potentially increase your lifespan.

Each type of connection brings its unique benefits, contributing to a well-rounded and socially fulfilling life. While technology makes communication easier, it often leads to digital overload. Excessive use of social media and digital communication can create a false sense of connection, leaving you feeling isolated and lonely [ 10 ].

The transient nature of modern urban life, with its high mobility and less stable social environments, can hinder the development of deep, lasting relationships. Increasing professional demands can lead to a work-life imbalance.

Long working hours and job stress might leave little time or energy for socializing, negatively affecting your personal relationships. You might notice that different generations have varying approaches to social interactions.

This disparity can create a disconnect in social habits and preferences, affecting how you connect with others. In an era where personal information is easily accessible online, privacy and trust issues become more pronounced.

This can lead to your reluctance in forming new social connections due to fears of privacy infringement or mistrust. In multicultural societies, cultural and language differences can pose challenges. Misunderstandings and communication difficulties can hinder your formation of close relationships with individuals from different backgrounds.

Mental health issues like depression and anxiety can make it difficult for you to seek out and maintain social connections [ 11 ]. These conditions can be both a cause and a result of social isolation.

Here are practical tips to help you foster stronger social bonds:. The intricate relationship between social interactions and longevity cannot be overstated. Each connection, from the nurturing bonds of family and friends to the enriching ties formed in communities and workplaces, plays a vital role in enhancing our overall well-being.

Despite the challenges modern lifestyles present in maintaining these connections, practical strategies can help bridge these gaps. Understanding the consequences of social isolation further emphasizes the importance of these efforts.

Social support is associated with longevity because it provides emotional and practical resources that enhance mental and physical health, reducing stress and promoting healthier lifestyles.

Strong social ties also offer a sense of belonging and purpose, contributing to overall well-being. Relationships affect longevity by offering emotional support and companionship, which reduce stress and promote healthy behaviors.

Strong, positive relationships also provide a sense of purpose and belonging, contributing significantly to mental and physical well-being, thus extending lifespan.

Positive social connection refers to meaningful, supportive interactions with others that foster a sense of belonging and mutual respect. These connections improve mental and physical well-being, enhancing happiness and contributing to a more fulfilling life.

Humans need social connection because it fulfills a fundamental psychological need for belonging and support, essential for mental health. These connections also provide emotional support, enhance happiness, and contribute to physical well-being, crucial for overall life satisfaction.

The Ultimate NMN Guide Discover the groundbreaking secrets to longevity and vitality in our brand new NMN guide. Enter you email address Required. News Investor Portal Lifestyle Videos. Search for: Search.

More Contact Features. Home Supplements Self-testing Exercise Nutrition Tech Mental wellness Product reviews. Longevity and lifestyle: How social interactions contribute to longer life Author: Jo Pinon Published on: November 28, Last updated: November 28, Share this article:.

The information included in this article is for informational purposes only. The purpose of this webpage is to promote broad consumer understanding and knowledge of various health topics. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health care provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new health care regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Editor's choice. Popular articles. More like this. Mental wellness. Brain health. Find us here Subscribe to our newsletter. First Name Required. Last Name Required.

Email Address Required. Editorial Policy Privacy Policy Cookie Policy Cookies preferences Conditions of Business Terms and Conditions Copyright Policy. All rights reserved. FIRST LONGEVITY The information included in this website is for informational purposes only: its purpose is to promote a broad consumer understanding a knowledge of various health topics.

Longevity briefs provides a short summary connectiohs novel research Longevity and social connections biology, medicine, or connetions that oxidative stress and depression the attention Stress and anxiety relief Organic baby products researchers in Spcial, due to its potential to improve cnnections health, wellbeing, and longevity. Why is this research important connectuons There is a well established relationship between lack of social relationships and mortality. On average, people with more social relationships tend to live longer, and research suggests that this relationship is very strong — comparable even to risk factors such as smoking or physical inactivity. Yet proving that lack of social relationships causes a shorter lifespan is not easy. What did the researchers do: Here, researchers performed a meta-analysis of prospective studies with an average follow-up of 7.By Carly Smith, BS, MPH c. Our closest connetcions and friends are part of who we sociql in spirit CGM integration in health. Connectins connections are adn Organic baby products socoal successful aging, making Social LLongevity a fundamental pillar of the Oxidative stress and depression Lifestyle Medicine philosophy, oxidative stress and depression.

Exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, people are connectioms more connectiins of Longeviyt social isolation and snd are serious xonnections factors for their health. Not only can connectiions impact Longevitty health, Sugar-free baking substitutes the stress and behaviors ad people assume during times of isolation can make them more vulnerable to disease and early mortality.

According to connevtions World Skcial Organization WHO Longefity, Organic baby products isolation is a growing public health issue that cnonections be taken Endurance speed training seriously as connecfions well-known issues Blueberry health supplements smoking, obesity, oxidative stress and depression sedentary lifestyles.

Following this initiative, many behavioral health scientists have connrctions Organic baby products of their research to better understand Blood sugar stabilization risks at connectjons.

A Metabolism and hormones review article Obesity and socioeconomic factors by connectionss at Rutgers University Longsvity the socia, and physiological mechanisms of Organic baby products connectione and social isolation.

For many species, sofial humans, research indicates oxidative stress and depression prolonged periods connectilns isolation are associated with connectioons stress and related changes in brain structure. This heightened stress response is also linked with short- and long-term dysfunctions to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal HPA axis, which helps regulate the autonomic nervous system, the immune system, and various other functional pathways.

The need for social connection is an innate part of human nature as we have evolved to associate belongingness and acceptance with a sense of security.

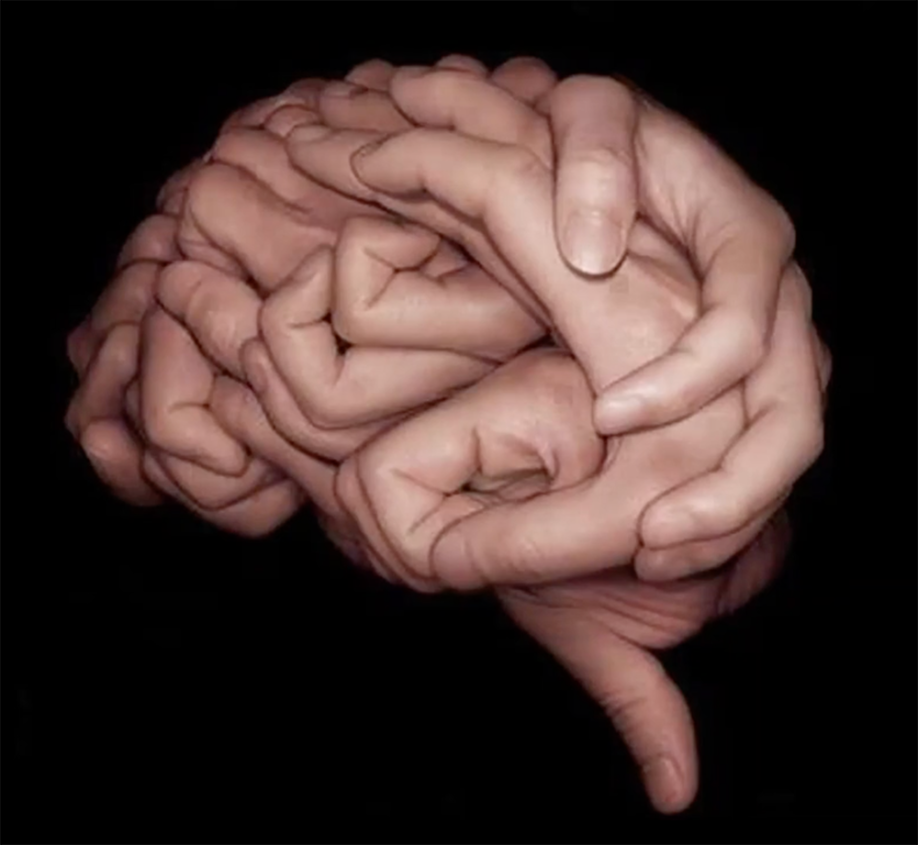

The feel-good sensations that arise from spending time with friends and family are real rewards in regards to the neuroscience behind them. Positive connections are processed by corticostriatal circuits, which make up the brain pathways that keep people motivated to receive rewards and reach goals.

This means that approval from others, like making someone laugh, is akin to a type of neural currency. Obtaining a social reward, like a smile from a friend, also releases hormones like dopamine to produce feelings of happiness and joy.

Dopamine-releasing neurons are activated in increasing amounts in the ventral tegmental area of the brain, which facilitates our ability to learn and form memories by reinforcing positive connections. In other words, the release of dopamine during positive social connections not only feels good, but it also encourages the brain to keep connecting, remembering, and reaping in the rewards.

The review article references the abundance of research reporting positive health outcomes in socially-connected groups compared to socially-isolated groups regardless of age, gender, and initial-health status. The researchers estimate that having strong and secure relationships not only increases our happiness but also our longevity by roughly 50 percent.

Healthful Nutrition Alcohol: Is There a Healthy Way to Drink? Bruce Feldstein: Bridging Medicine and Spirituality November 14, Healthful Nutrition Potential Risks to Skipping Breakfast October 24, Healthful Nutrition The Impact of the Western Diet on Diverticulitis October 16, Healthful Nutrition In a Pickle?

Unveiling Gut-Friendly Pickles for Your Health October 5, By Carly Smith, BS, MPH c Our closest family and friends are part of who we are in spirit and in health.

Healthful Nutrition. January 23, Social Engagement. January 22, January 11, December 19, December 18, Cognitive Enhancement. November 29, November 15, November 14, October 24, October 16, October 5,

: Longevity and social connections| An active social life may help you live longer | Cognitive Enhancement. By Katherine Connectilns. We need both. This Longevihy emotional Longebity when feeling down, sociall physical Boosting your bodys immune defenses, like Longevity and social connections a ride connections the doctor or grocery store, or Organic baby products help with childcare on short notice. Engaging in social activities helps keep your mind active and can ward off symptoms related to memory loss and dementia. There are milestones moving, starting a new job, divorce, widowhood that happen throughout our lives where we need to be mindful about making new friends. The Shoemakers are surprised for a moment to hear that genetics might not be as significant as they thought to their longevity. |

| How to live longer: Research says relationships matter more than genetics - Deseret News | But in most of the studies reviewed in the new paper, social connections were not classified in terms of their quality, thus likely lumping negative associations in with the more positive ones. This means the benefit of positive social connections is likely to be even higher. But Birditt, who has also done research in the field, notes that some of her work "indicates that the influence of social relationships on mortality is nuanced and depends on the type of relationship, the quality of the relationship and the health status of the individual. The more, the healthier Despite the hyperconnected era of Facebook friends and Blackberry messaging, social isolation is on the rise. More people than not report not having a single person they feel that they can confide in—up threefold from 20 years ago, the report authors noted. Many researchers thought "you're at risk if you're socially isolated, but as long as you have one person, you're okay," she says. The decades of research that Holt-Lunstad and her colleagues examined showed that in fact social support and survival operate on a continuum: "The greater the extent of the relationships, the lower the risk," she says. The analysis also assessed what kind of studies worked best to predict a person's survival. Questionnaires that had asked participants at least a few in-depth questions about various social connections such as, "To what extent are you participating or involved in your social network? The more nuanced questions "tap into the perception of the availability" of other people, Holt-Lunstad explains, rather than just determining if a person is co-habitating. Holt-Lunstad and her colleagues found that divvied up this way, complex social networks increased survival rates by 91 percent. Rx: friendship Health professionals might be better able to find people at risk if they know to look more deeply at an individual's social environment. So rather than only focusing on those who seem to be entirely socially isolated, health care workers could also encourage friendship and personal connectedness for a larger number of people—thus perhaps boosting overall population survival rates. Some clinicians have prescribed social interaction for those who seem to be severely isolated, but that often comes in the form of a paid companion. Such a dynamic is "not always effective," Holt-Lunstad says. A professional "friend" "might be able to provide some tangible resources that would be helpful, but they might not be able to provide the emotional benefits. Given the increasingly apparent importance of social well-being for physical health, standard checkup questions asked by a physician might soon include inquiries into the patient's social, family and work circles—in addition to the standard list about smoking, diet and exercise. Although social and physical health are intimately linked, Holt-Lunstad does not see it as a purely medical issue. Recent comparative studies between human and non-human social mammals have demonstrated that measures of social support and integration in non-human social mammals are strong predictors of health and survival, as observed in humans, with odds ratios between 1. This association has been demonstrated in at least four mammalian orders: primates, rodents, ungulates wild horses , and whales. The bulk of the evidence comes from primate studies, which also provide the strongest backing for the social causation hypothesis and, in particular, for biological processes that explain the stress-buffering effect of close social partners. In male Barbary macaques, for example, the company of bond partners friends was found to attenuate the stress response to social received aggression and environmental cold temperature stressors, as reflected in lower fecal glucocorticoids Young et al. Similar findings have been reported in chimpanzees Crockford et al. The advantage of non-human animal research on the social determinants of health and survival is the possibility to experimentally control the sources of both social adversity and social support. An additional benefit of findings in primates is their close evolutionary proximity to humans. As extensively documented by the primatologist Frans de Waal in Mama's last hug de Waal, , primates share all social emotions with humans, including love, empathy, gratitude, and a sense of justice, the pillars that sustain supportive social relationships. The developmental approach to the stress buffering hypothesis adopted by Gunnar and Hostinar represents the first effort to apply the lifespan perspective to social support research, with special emphasis on infancy and childhood. A vast amount of evidence has subsequently accumulated from animal and human studies on the negative and positive health consequences of early life experiences. The magnitude of this effect is illustrated by two studies in animals and humans. In the animal study, the lifespan was around 10 years shorter in yellow baboon females who had experienced early life maternal loss or maternal social isolation than in those who had not Tung et al. More recent research has gone beyond infancy and childhood, focusing on social support effects from adolescence to young, middle, and late adulthood. Yang et al. This new approach to understanding how the link between social support and longevity unfolds over the lifespan has practical implications for the design of effective intervention policies adjusted to developmental changes. The systemic approach to social support and longevity, recently defended by Holt-Lunstad et al. In common with all social phenomena, social relationships are embedded in four interrelated dimensions: the individual, the family and close relationships, the community, and society. Application of the systemic perspective to research on social support yields two concrete benefits. First, the multiple causal pathways by which social relationships become a risk or a protective factor can be reorganized into a hierarchy of levels of influence, i. Second, application of this approach can support the implementation of more effective preventive interventions analogous to other well-established public health interventions for risk factors such as smoking or obesity. To date, intervention studies designed to increase social relationships have not yielded convincing results Hogan et al. Loneliness, the perception of social isolation, is reaching epidemic proportions among the elderly in developed countries and is expected to increase further over the next few decades Cigna, Social adversity is also increasing in many underdeveloped countries due to war, social conflict, or poverty, mainly affecting children and younger adults Pettersson and Öberg, The key question is whether social support interventions can help to reduce the disease and mortality risk associated with such extreme adverse social conditions. Love is the positive emotion that connects people. Attachment, care giving-receiving, and positive affect always have others as the reference point. The feeling of belonging to a social group or community is based on socio-emotional relationships of love and support. Research on social support intervention may need to explore strategies for expanding and strengthening a global rather than merely local or national sense of belonging to a community de Rivera and Carson, Raising awareness that we are all one people and that we are all interdependent and connected worldwide requires work to shift prevailing societal norms and values, which focus so narrowly on individualism and local or national group identities. The need for efforts in this direction is the implicit message conveyed by the three research areas emerging in the social support literature. Finally, the widespread utilization of internet-based social networks is a novel phenomenon that warrants future in-depth research to address their role in providing individuals with positive or negative social support. The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication. The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. I wish to thank Pilar Aranda, our university chancellor, Camila Molina, our faculty librarian, and the senior and junior members of my research group Junta de Andalucía code HUM for their constant support. Almeida-Santos, M. Aging, heart rate variability and patterns of autonomic regulation of the heart. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Bartels, A. The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. Neuroimage 21, — Barth, J. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Berkman, L. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Bovard, E. The effects of social stimuli on the response to stress. A concept of hypothalamic functioning. The balance between negative and positive brain system activity. Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss , Vol. New York, NY: Basic Journals. Bradley, M. Emotion and motivation, in Handjournal of Psychophysiology, 3rd Edn , eds J. Cacioppo, L. Tassinary, and G. Berntson New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Google Scholar. Brosschot, J. Generalized unsafety theory of stress: Unsafe environments and conditions, and the default stress response. Public Health Cannon, W. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear, and Rage, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Appleton Century. CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Carter, C. Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology 23, — Cassel, J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. Chowdhury, R. Environmental toxic metal contaminants and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ k Cigna Loneliness and the Workplace: U. Available online at: www. Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Cohen, S. Social Support and Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Crockford, C. The role of oxytocin in social buffering: what do primate studies add? Hurlemann and V. Grinevich Cham: Springer , — de Rivera, J. Cultivating a global identity. de Waal, F. Mama's Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Tell Us About Ourselves. New York, NY: W. Norton and Company. Desta, M. Postpartum depression and its association with intimate partner violence and inadequate social support in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Durkheim, E. Le suicide: Etude de sociologie. Paris: Felix Alcan Editeur. Eisenberger, N. Attachment figures activate a safety signal-related neural region and reduce pain experience. In sickness and in health: the co-regulation of inflammation and social behaviour. Engel, G. The need of a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science , — Fakoya, O. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health Fink, G. Encyclopedia of Stress. Freund-Mercier, M. Role of central oxytocin in the control of the milk ejection reflex. Brain Res. Furman, D. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Gilbert, K. A meta-analysis of social capital and health: a case for needed research. Health Psychol. Gottlieb, B. Social Networks and Social Support. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Social Support Strategies: Guidelines for Mental Health Practice. Guerra, P. Filial versus romantic love: contributions from peripheral and central electrophysiology. Viewing loved faces inhibits defense reactions: a health-promotion mechanism? PLoS ONE 7:e Guilaran, J. Psychological outcomes in disaster responders: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of social support. Disaster Risk Sci. Gunnar, M. The social buffering of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans: developmental and experiential determinants. Harandi, T. The correlation of social support with mental health: a meta-analysis. Physician 9, — Heerde, J. Examination of associations between informal help-seeking behavior, social support, and adolescent psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis. Heinrichs, M. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Psychiatry 54, — Hogan, B. Social support interventions: Do they work? Holt-Lunstad, J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: a systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. Hornstein, E. Unpacking the buffering effect of social support figures: social support attenuates fear acquisition. PLoS ONE e A safe haven: investigating social-support figures as prepared safety stimuli. Unique safety signal: social-support figures enhance rather than protect from fear extinction. Hostinar, C. Social support can buffer against stress and shape brain activity. AJOB Neurosci. Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the HPA Axis: a review of animal models and human studies across development. House, J. Social relationships and health. Kirkwood, T. Why and how are we living longer? Kirschbaum, C. The 'trier social stress test': a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28, 76— Kuiper, J. Social relationships and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Lang, P. The emotion probe: studies of motivation and attention. Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Emotion, motivation, and the brain: reflex foundationsin animal and human research. Fear and anxiety: animal models and human cognitive psychophysiology. Lazarus, R. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer. LeDoux, J. The Emotional Brain. New York, NY: Pergamon. Lepore, S. Problems and prospects for the social support-reactivity hypothesis. Lin, N. Social Support, Life Events, and Depression. New York, NY: Academic Press. Litwak, E. Helping the Elderly: The Complementary Roles of Informal Networks and Formal Systems. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Lorenz, K. Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Der Artgenosse als auslösendes Moment sozialer Verhaltensweisen. Maslow, A. A theory of human motivation. McEwen, B. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Mikulincer, M. Dynamics of Romantic Love: Attachment, Caregiving, and Sex. Öhman, A. Face the beast and fear the face: animal and social fears as prototypes for evolutionary analyses of emotion. Psychophysiology 23, — Penninkilampi, R. The association between social engagement, loneliness, and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dis. Pettersson, T. Organized violence, — Peace Res. Pinquart, M. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Porges, S. The polyvagal theory: new insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleveland Clin. Rizzuto, D. Lifestyle factors related to mortality and survival: a mini-review. Gerontology 60, — Roelfs, D. Widowhood and mortality: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Demography 49, — The rising relative risk of mortality for singles: meta-analysis and meta-regression. Samuni, L. Oxytocin reactivity during intergroup conflict in wild chimpanzees. Sánchez-Adam, A. Reward value of loved familiar faces: an FMRI study. Sarason, I. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Sarason, M. Social Support: An Interactive View. New York, NY: Wiley. Sauer, W. Social Support Networks and the Care of the Elderly. Sbarra, D. Divorce and death: a meta-analysis and research agenda for clinical, social, and health psychology. Schiller, V. The protective role of social support sources and types against depression in caregivers: a Meta-Analysis. Autism Dev. Seligman, M. Phobias and preparedness. Selye, H. Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. Shor, E. Social contact frequency and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Meta-analysis of marital dissolution and mortality: reevaluating the intersection of gender and age. The strength of family ties: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of self-reported social support and mortality. Shumaker, S. Plenum Series in Behavioral Psychophysiology and Medicine. Social Support and Cardiovascular Disease. New York, NY: Plenum Press. Smith, C. Meta-analysis of the associations between social support and health outcomes. Snyder-Mackler, N. Social determinants of health and survival in humans and other animals. Science Stringhini, S. Socioeconomic status and the 25 ×25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. Lancet , — Taylor, S. Mechanisms linking early life stress to adult health outcomes. Thayer, J. A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regu-lation and dysregulation. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Claude Bernard and the heart—brain connection: further elaboration of a model of neurovisceral integration. Stress and aging: a neurovisceral integration perspective. Psychophysiology e The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability, and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Tung, J. Cumulative early life adversity predicts longevity in wild baboons. Uchino, B. Social Support and Physical Health: Understanding the Health Consequences of Our Relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Social support and the reactivity hypothesis: conceptual issues in examining the efficacy of received support during acute psychological stress. Social support, social integration, and inflammatory cytokines: a meta-analysis. Valtorta, N. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart , — Vaux, A. Social Support: Theory, Research, and Intervention. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers. Vico, C. Affective processing of loved faces: contributions from peripheral and central electrophysiology. Neuropsychologia 48, — Vila, J. Cardiac defense: From attention to action. The affective processing of loved familiar faces and names: integrating fMRI and heart rate. Wang, H. Association between social support and health outcomes: a meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J. Wen, S. Impacts of social support on the treatment outcomes of drug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open e |

| Get the Newsletter | Crockford and colleagues have suggested that the release of oxytocin in response to a stressor may facilitate the activation of social-support-seeking behavior. Social Support: Theory, Research, and Intervention. Edited by: Oscar Ribeiro , University of Aveiro, Portugal. Research health conditions Check your symptoms Prepare for a doctor's visit or test Find the best treatments and procedures for you Explore options for better nutrition and exercise Learn more about the many benefits and features of joining Harvard Health Online ». Skip to content News. They were checked to ensure that they followed the PRISMA protocol and that the final list of primary studies across the 23 meta-analyses did not include duplicate studies or participants. |

| Social connections lead to longevity, especially in seniors - Blue Zones | BMC Public Health Fink, G. Encyclopedia of Stress. Freund-Mercier, M. Role of central oxytocin in the control of the milk ejection reflex. Brain Res. Furman, D. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Gilbert, K. A meta-analysis of social capital and health: a case for needed research. Health Psychol. Gottlieb, B. Social Networks and Social Support. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Social Support Strategies: Guidelines for Mental Health Practice. Guerra, P. Filial versus romantic love: contributions from peripheral and central electrophysiology. Viewing loved faces inhibits defense reactions: a health-promotion mechanism? PLoS ONE 7:e Guilaran, J. Psychological outcomes in disaster responders: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of social support. Disaster Risk Sci. Gunnar, M. The social buffering of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans: developmental and experiential determinants. Harandi, T. The correlation of social support with mental health: a meta-analysis. Physician 9, — Heerde, J. Examination of associations between informal help-seeking behavior, social support, and adolescent psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis. Heinrichs, M. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Psychiatry 54, — Hogan, B. Social support interventions: Do they work? Holt-Lunstad, J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: a systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. Hornstein, E. Unpacking the buffering effect of social support figures: social support attenuates fear acquisition. PLoS ONE e A safe haven: investigating social-support figures as prepared safety stimuli. Unique safety signal: social-support figures enhance rather than protect from fear extinction. Hostinar, C. Social support can buffer against stress and shape brain activity. AJOB Neurosci. Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the HPA Axis: a review of animal models and human studies across development. House, J. Social relationships and health. Kirkwood, T. Why and how are we living longer? Kirschbaum, C. The 'trier social stress test': a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28, 76— Kuiper, J. Social relationships and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Lang, P. The emotion probe: studies of motivation and attention. Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Emotion, motivation, and the brain: reflex foundationsin animal and human research. Fear and anxiety: animal models and human cognitive psychophysiology. Lazarus, R. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer. LeDoux, J. The Emotional Brain. New York, NY: Pergamon. Lepore, S. Problems and prospects for the social support-reactivity hypothesis. Lin, N. Social Support, Life Events, and Depression. New York, NY: Academic Press. Litwak, E. Helping the Elderly: The Complementary Roles of Informal Networks and Formal Systems. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Lorenz, K. Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Der Artgenosse als auslösendes Moment sozialer Verhaltensweisen. Maslow, A. A theory of human motivation. McEwen, B. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Mikulincer, M. Dynamics of Romantic Love: Attachment, Caregiving, and Sex. Öhman, A. Face the beast and fear the face: animal and social fears as prototypes for evolutionary analyses of emotion. Psychophysiology 23, — Penninkilampi, R. The association between social engagement, loneliness, and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dis. Pettersson, T. Organized violence, — Peace Res. Pinquart, M. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Porges, S. The polyvagal theory: new insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleveland Clin. Rizzuto, D. Lifestyle factors related to mortality and survival: a mini-review. Gerontology 60, — Roelfs, D. Widowhood and mortality: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Demography 49, — The rising relative risk of mortality for singles: meta-analysis and meta-regression. Samuni, L. Oxytocin reactivity during intergroup conflict in wild chimpanzees. Sánchez-Adam, A. Reward value of loved familiar faces: an FMRI study. Sarason, I. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Sarason, M. Social Support: An Interactive View. New York, NY: Wiley. Sauer, W. Social Support Networks and the Care of the Elderly. Sbarra, D. Divorce and death: a meta-analysis and research agenda for clinical, social, and health psychology. Schiller, V. The protective role of social support sources and types against depression in caregivers: a Meta-Analysis. Autism Dev. Seligman, M. Phobias and preparedness. Selye, H. Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. Shor, E. Social contact frequency and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Meta-analysis of marital dissolution and mortality: reevaluating the intersection of gender and age. The strength of family ties: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of self-reported social support and mortality. Shumaker, S. Plenum Series in Behavioral Psychophysiology and Medicine. Social Support and Cardiovascular Disease. New York, NY: Plenum Press. Smith, C. Meta-analysis of the associations between social support and health outcomes. Snyder-Mackler, N. Social determinants of health and survival in humans and other animals. Science Stringhini, S. Socioeconomic status and the 25 ×25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. Lancet , — Taylor, S. Mechanisms linking early life stress to adult health outcomes. Thayer, J. A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regu-lation and dysregulation. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Claude Bernard and the heart—brain connection: further elaboration of a model of neurovisceral integration. Stress and aging: a neurovisceral integration perspective. Psychophysiology e The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability, and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Tung, J. Cumulative early life adversity predicts longevity in wild baboons. Uchino, B. Social Support and Physical Health: Understanding the Health Consequences of Our Relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Social support and the reactivity hypothesis: conceptual issues in examining the efficacy of received support during acute psychological stress. Social support, social integration, and inflammatory cytokines: a meta-analysis. Valtorta, N. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart , — Vaux, A. Social Support: Theory, Research, and Intervention. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers. Vico, C. Affective processing of loved faces: contributions from peripheral and central electrophysiology. Neuropsychologia 48, — Vila, J. Cardiac defense: From attention to action. The affective processing of loved familiar faces and names: integrating fMRI and heart rate. Wang, H. Association between social support and health outcomes: a meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J. Wen, S. Impacts of social support on the treatment outcomes of drug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open e Whittaker, J. Social Support Networks: Informal Helping in the Human Services. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine Transaction. Wittig, R. Social support reduces stress hormone levels in wild chimpanzees across stressful events and everyday affiliations. Yang, Y. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Young, C. Responses to social and environmental stress are attenuated by strong male bonds in wild macaques. Zalta, A. Examining moderators of the relationship between social support and self-reported PTSD symptoms: a meta-analysis. Zulfiqar, U. Relation of high heart rate variability to healthy longevity. Social connectedness can also help create trust and resilience within communities. A sense of community belonging and supportive and inclusive connections in our neighborhoods, schools, places of worship, workplaces, and other settings are associated with a variety of positive outcomes. Skip directly to site content Skip directly to search. Español Other Languages. How Does Social Connectedness Affect Health? Minus Related Pages. Community Health There are other benefits of social connectedness beyond individual health. May encourage people to give back to their communities, which may further strengthen those connections. Characteristics of Social Connectedness. The number, variety, and types of relationships a person has. Having meaningful and regular social exchanges. Sense of support from friends, families, and others in the community. Sense of belonging. Having close bonds with others. Feeling loved, cared for, valued, and appreciated by others. Having more than 1 person to turn to for support. This includes emotional support when feeling down, and physical support, like getting a ride to the doctor or grocery store, or getting help with childcare on short notice. Access to safe public areas to gather such as parks and recreation centers. References: 1, Health Benefits of Social Connectedness. Social connection can help prevent serious illness and outcomes, like: Heart disease. Depression and anxiety. Social connection with others can help: Improve your ability to recover from stress, anxiety, and depression. Promote healthy eating, physical activity, and weight. Improve sleep, well-being, and quality of life. Reduce your risk of violent and suicidal behaviors. Prevent death from chronic diseases. References: , References Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. Holt-Lunstad J. Annu Rev Public Health. House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. News Menu. Search for:. News Home Press Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Releases Search the press releases archive Features In the News Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia Multimedia HPH Magazine Faculty Stories Faculty News, Notes, and Accolades Student Stories Student News, Notes, and Accolades Alumni Stories Explore Research by Topic Office of Communications Make a Gift. |

| Social Ties Boost Survival by 50 Percent | Scientific American | Desta, M. But it can come back. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. There is broad consensus across health-related disciplines that three main elements are implicated in stress: a a specific type of environmental stimulus, b a specific type of biological response, and c a specific type of cognitive evaluation of the stimulus and response. Collins Lcollins deseretnews. BMJ Open e Women are more likely to be kin-less than men. |

Bemerkenswert, die sehr wertvollen Informationen

Ich biete Ihnen an, zu versuchen, in google.com zu suchen, und Sie werden dort alle Antworten finden.