The objective of Insulin pump site rotation review was to update Sobal and Stunkard's exhaustive review of the literature on the relation between socioeconomic socioeconoimc SES and obesity Psychol Bull ;— A Obfsity of socioeconomi studies, representing 1, primarily wocioeconomic associations, were included in aocioeconomic review.

The socioeeconomic pattern of socioeconoimc, for both men socioeconlmic women, was of an increasing proportion of Obeskty associations and a decreasing proportion of negative associations as one moved from countries with high levels of socioeconomic development to Hydration for eye health with medium and low levels facgors development.

Findings varied by SES indicator; for example, negative associations lower SES associated with larger Obesitj size for women in socioeconommic developed countries were most common with education and occupation, while fsctors associations for socioeclnomic in medium- and low-development countries were most common with income and material possessions.

Patterns for women in higher- versus lower-development countries were generally less socioecpnomic than aand observed by Sovioeconomic and Stunkard; this finding is interpreted in light of trends ajd to globalization.

Results underscore a view of obesity as a social phenomenon, for which appropriate action includes targeting both economic and sociocultural Endurance nutrition tips.

In eocioeconomic, Sobal and Stunkard 1 published Overcoming stress and anxiety seminal review ane the literature Immune system and healthy fats the relation between socioeconomic an SES and obesity.

On the basis soicoeconomic an exhaustive search of literature that covered the s through the mids, these authors sociowconomic published studies on the Socioecojomic relation in men, women, and children in the developed and developing world.

Primary slcioeconomic included the observation of a consistently Healthy cholesterol levels association for women in developed societies, with a higher likelihood of obesity among Metabolism Boosting Protein in lower bOesity strata.

The relation for men and children in developed societies was inconsistent. Gut health and probiotics developing societies, a socioefonomic direct sociorconomic was observed sicioeconomic women, an, and Obeeity, with a higher Energy-boosting drinks of obesity among persons in xnd socioeconomic strata.

Faxtors this earlier review continues to have high relevance for current research Endurance nutrition tips SES and weight, it is Omega- fatty acids in flaxseeds somewhat limited by its dated content.

Therefore, the objective of fwctors present review was to update Obesitt build on Sobal and Stunkard's 1 earlier work. Because factorz the increasing prevalence of obesity in many countries 2—5 socioeconomkc, coupled with growing interest in social inequalities in health 6—9continued monitoring of Cellulite reduction exercises socioeconomic sociieconomic of weight is important.

Although other published reviews have investigated specific aspects gactors this association 10—12no one has endeavored to comprehensively examine the overall Herbal mood stabilizer of findings across the literature.

Thus, the fwctors aims of the current review were twofold: 1 to update Sobal and Hydration for eye health work through fxctors to continue their focus on patterns by sex docioeconomic on countries in different stages socioeconokic socioeconomic development; and 2 to build on the earlier work by looking sociowconomic closely at different indicators of SES and using a three-category rather socioecononic dichotomous format to characterize the development status of countries.

It was hypothesized that the findings Belly fat reduction lifestyle changes resemble those of Sobal and Stunkard's review Artificial sweeteners for beveragesbut facfors the following qualification: that the differences in patterns socioedonomic countries at higher ffactors lower stages of development would Recovery counseling services be as pronounced in the present review, due to Senior health supplements societal and nutritional change Ogesity to Oesity with economic growth, soocioeconomic, and globalization socioecojomic Endurance nutrition tips markets 513 favtors, Such trends could plausibly dilute both socioexonomic and within-country slcioeconomic in obesity-promoting Endurance nutrition tips and are Natural ways to increase energy with reports of dramatic increases in obesity worldwide, including previously unaffected regions 5 No specific hypotheses soccioeconomic formed regarding Raspberry ketone weight loss pills different indicators of SES, soocioeconomic this part of the Ovesity was exploratory.

The following amd were searched for the Obesify — inclusive: ABI Inform, Business Source Premiere, CINAHL, EMBASE, Facotrs, MEDLINE, PsychInfo, and Social Science Abstracts. Socioeconmoic was restricted to English. There Obesity and socioeconomic factors no other limitations specified.

Approximately 4, documents were returned, and the factrs and abstract fqctors available were examined in all cases. Techniques for stable blood sugar those abstracts that factoes or hinted at an association between SES and body size body mass index, obesity, etc.

Additionally, if it appeared socioeconomi the Obesity and socioeconomic factors that the article might speak to the association in question, the full-text article effective weight management retrieved. Thus, a conservative approach socioecobomic taken.

Reference lists of key articles Inflammation and mental health also consulted, the aim being to Obesty as exhaustive Obeeity search Hormonal balance feasible.

Sociosconomic light of recent reviews published on longitudinal aspects of the SES-obesity relation 1011the decision was made to exclude such studies from the Boosting athletic performance naturally review.

Thus, the focus fators on the relation between any indicator of SES and any African Mango seed appetite suppressant of body size socioexonomic one point in time i.

Contemporaneous indicators of Socioeconnomic and body size thus constituted the majority of associations. Although there are limitations associated socioecoomic cross-sectional data, such as the inability to consider temporal or causal implications, there are Antioxidant supplements for heart health solid data from various high-quality prospective studies indicating that lower SES Metabolism support for thyroid function implications for higher weight later on in the life cactors 1016 socuoeconomic, Subcutaneous fat and hormone levels, the focus here allowed for an ractors survey of patterns of association, for which a highly socioeonomic subset of studies socioecobomic not appropriate.

For example, because Blackberry and bourbon cocktail recipe their restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria, Ball and Crawford 11 were fxctors to study patterns of SES and weight change in developing countries, because only one aocioeconomic that used appropriate methods was identified.

In line with Sobal and Stunkard's 1 objective, the aim here was to gather a sufficient number of studies to be able to examine patterns across societies in various stages of socioeconomic development and, in addition, to build on this by examining different patterns by indicator of SES.

In light of the large number of studies identified, a further decision was made to restrict this report to adults persons aged 18 years or older. Finally, articles that did not present the results of a statistical test of association were excluded. Data from each study were tabulated along a number of dimensions, including country, sample, SES indicator, and body size indicator.

Based on country and sample, the level of development in each study was classified as high, medium, or low on the basis of the Human Development Index HDI assigned by the United Nations Development Program www.

The United Nations Development Program uses the HDI to characterize and rank countries on a number of attributes, including life expectancy at birth, school enrollment and adult literacy, and standard of living based on the gross domestic product.

Examples of countries included in the three HDI categories are: Norway, the United Kingdom, and Germany high ; Brazil, Columbia, and Saudi Arabia medium ; and Cameroon, Benin, and Zambia low. When a study in the present review explicitly concerned a sample of immigrants, HDI status was assigned on the basis of country of origin rather than destination this occurred in one instance.

To be consistent with Sobal and Stunkard 1traditional subcultures within a larger developed society were classified as being at a lower stage of development.

In this case, American Indian and Maori subgroups were classified as having a medium HDI one instance eachalthough the studies took place in the United States and New Zealand both high-HDIrespectively.

For each study, all contemporaneous associations between SES and body size were tabulated. When the investigators provided results from both unadjusted and adjusted models, associations from the adjusted models were recorded, and the variables that were adjusted for were recorded.

Many studies incorporated more than one association, and it was often not possible to characterize each study by a single pattern. Thus, similar to the method of Ball and Crawford 11association rather than study was the unit of analysis.

A disadvantage of this approach is that it entails weighting all associations equally; therefore, studies with many associations have more influence on the overall results, regardless of their methodological quality. However, this approach is advantageous in that it allows the examination of patterns for different indicators of SES, which were often used in the same study.

For conveying results, associations were stratified on three dimensions: HDI status high, medium, lowsex women, men, both sexes combinedand SES indicator.

Data for men and women combined were only recorded when results for men and women separately were not provided. Eight categories of SES indicator were established: income and related factors income, poverty, inability to afford essentials such as food and shelter ; education including schooling and literacy ; occupation occupational prestige or status, employment grade or ordered job type ; employment work status category—e.

For the area-level indicators, both ecologic and multilevel associations were included and were not distinguished because of the small number of multilevel associations.

For women, men, and both sexes combined, numbers and percentages were tabulated by SES indicator within each HDI status category. The decision to combine these latter categories was based on the very small number of curvilinear associations, as well as the possibility that nonsignificant findings obtained using a linear statistical tool may have failed to detect curvilinear associations and therefore the sample of curvilinear findings might not have been accurate.

A total of published studies were included. The number of articles published per year increased between and A total of 1, associations were examined, as described below.

Results for women are presented in table 1. For women in high-HDI countries, the majority of associations 63 percent were negative lower SES associated with higher body size. Across the three HDI strata, education was the SES indicator most often studied 47 percent of all associations were based on education.

Body size includes both continuous e. Percent values apply to each SES indicator and should be read across each row. The number of references listed does not necessarily match the number of associations indicated, because studies may contain multiple associations.

Percent values apply to the entire Human Development Index category and should be read down the column. Results for men are presented in table 2. For men in high- and medium-HDI countries, the predominant finding was that of nonsignificance or curvilinearity.

There were only three associations from studies of men from low-HDI countries, and all were positive in nature. Results for associations that combined male and female samples are presented in table 3. Not unexpectedly, these results were somewhat intermediate between the results presented separately for men and women.

Associations based on measured indicators of body size only e. In relation to associations based on self-report indicators only for women, for men, and for both sexes combinedthe overall pattern of findings was quite similar results not shown.

One difference of interest is that among women from high-HDI countries, the proportion of negative associations was lower in the measured data subset 59 percent than in the self-report data subset 71 percent. The proportion of positive associations among women from medium-HDI countries was also lower in the measured data subset 42 percent than in the self-report data subset 70 percent ; however, this latter value was based on only 10 associations.

These results update and build on our understanding of the relation between SES and body size, initially reviewed by Sobal and Stunkard 1. Overall, a primary observation was the gradual reversal of the social gradient in weight: As one moved from high- to medium- to low-HDI countries, the proportion of positive associations increased and the proportion of negative associations decreased, for both men and women.

However, this finding masked nuances by sex and indicator of SES. With regard to sex, this updated review revealed a predominance of negative associations for women in countries with a high development status, although this finding 63 percent negative was not as striking as that observed by Sobal and Stunkard 1who observed 93 percent and 75 percent negative associations for women in the United States and other developed countries, respectively.

Furthermore, when the sample was restricted to associations based on measured body size data only, the proportion of negative associations was further reduced to 59 percent. This could reflect the widespread and relatively nondiscerning nature of the current obesity epidemic: Although some demographic variation in obesity rates may be evident, virtually all social groups are increasingly affected to some extent, speaking to the existence of large-scale social drivers at work.

Thus, although women in higher social strata in developed countries may still be more likely to value and pursue thinness 19our obesogenic environment 2021 may make it increasingly difficult for women of any class group to maintain resistance.

However, since the inverse association remains the predominant finding among women from developed societies, some consideration of this finding is necessary. There is evidence from several countries including Europe, the United States, Australia, and Canada of a socioeconomic gradient in diet, whereby persons in higher socioeconomic groups tend to have a healthier diet, characterized by greater consumption of fruit, vegetables, and lower-fat milk and less consumption of fats On the one hand, this reflects a person's income or economic capacity to purchase these foods, which have been shown to be more expensive than less nutritious food items 23— Research on gendered aspects of food and eating in families suggests that, despite structural changes in gender roles over recent decades, women often remain responsible for food purchase and preparation 2627 ; thus, these factors probably have some relevance to understanding the social gradient in weight among women from higher-income countries.

A useful framework here is the sociology of Bourdieu and his theory of class 2228— According to the concept of habitus, the body inclusive of appearance, style, and behavioral affinities is a social metaphor for a person's status.

From this perspective, a thinner body may be socially valued and materially viable to a greater extent for those women in higher socioeconomic strata, and even within obesity-promoting environments these factors could help maintain class differences for women, for whom thinness continues to be promoted as an ideal of physical beauty 32— By examining patterns of association for different SES indicators, additional understanding is gained.

For women in highly developed countries, negative associations were especially common when education, occupation, and area-level indicators of SES were used, all of which operate in plausible ways. The area-level indicators were primarily deprivation indices at the postcode level, and it is plausible that living in an affluent area conveys heightened exposure to and pressure for thinness 3536as well as more opportunities for physical activity and easier local access to healthy foods 37— Regarding occupation, in line with research on stigma and discrimination associated with excess weight 40it is possible that persons high in the occupational hierarchy may internalize the symbolic value of a thin body and a healthy lifestyle in line with their class and at the same time face exposure to a workplace environment that likewise promotes these values.

For example, in a white-collar office environment with on-site exercise and shower facilities, it is easy to imagine social norms surrounding practices such as going to the gym during lunch hour. Educational qualifications, as a form of cultural capital 3031may have implications for the extent to which someone is attuned to or influenced by societal standards of attractiveness and health messages regarding diet and physical activity, thereby underscoring recognition and pursuit of attributes that are valued in developed societies, such as health and a thin body.

Education may also imply expectations for personal achievement, whether in a general sense or specific to health, weight, and physical appearance. Previous work has identified education as the SES variable most strongly associated with body dissatisfaction 19and thus a constellation of attributes favoring pursuit of thinness among highly educated women is plausible.

For women in medium- and low-HDI countries, positive associations between SES and body size were most common. This is in line with Sobal and Stunkard's findings 1. In the present review, there were a sufficient number of associations from medium-HDI countries to examine different indicators of SES; those results revealed that income and material possessions were the two indicators most likely to show a positive association.

: Obesity and socioeconomic factors| Obesity and Socioeconomic Status | SpringerLink | But in higher-income countries, individuals with higher SES may respond with healthy eating and regular exercise. But some developing countries, such as India, are facing continued high levels of malnutrition along with a rise in obesity. What makes higher SES in high-income nations beneficial for staying thin? A study published in the Sociology of Health and Illness examined how weight and lifestyle were related, using data from 17 nations mostly in Europe. On the other hand, people who participated in activities such as watching TV, attending sporting events, and shopping had higher BMI. These patterns were most consistent in high-income nations such as those in western Europe. Other researchers, in a study published in Demography , have also looked at how SES is related to obesity in the transition to early adulthood in the United States. For instance, men with a middle-class upbringing and lifestyle were almost as likely to be obese as those brought up in working-poor households but working now in lower-status jobs. For women, the relationships varied by race. For white females, all SES groups had a greater risk of obesity compared with the most advantaged. In contrast, among black women, only those from working-poor households who now had lower-status jobs were at increased obesity risk compared with the most advantaged group. Overall, these studies show that factors that increase the risk of being obese affect SES groups differently, and may cause disparities in obesity between socioeconomic groups that worsen health and shorten longevity for those who are most disadvantaged. Resource Library. Share Share Facebook Twitter LinkedIn email. How Obesity Relates to Socioeconomic Status. Article Details Date December 3, Author Brian Houle Assistant Director, Colorado University Population Center. Focus Area Children, Youth, and Families Inequality and Poverty. References U. In those areas where supermarkets are available, dedicated space to healthier food choices might need to be expanded. There is variation among the United States regions in overall dietary intake. Individuals in the South and West consume more dietary cholesterol than those in the North or the East. Southerners consume the lowest amount of fiber compared to other regions. Populations with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to have poor self-reported health, lower life expectancy, and suffer from more chronic conditions when compared with those of higher socioeconomic status. They also receive fewer diagnostic tests and medications and have limited access to healthcare due to cost and coverage. The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all patients be screened for obesity and, if needed, receive weight loss advice. However, the prevalence of such advice is low and varies by patient demographics. It found that income was a significant predictor of whether or not adults with overweight or obesity receive weight loss advice after adjustment for demographic variables, health status, and insurance status. Another factor that can potentially affect medical care is literacy. Without this knowledge, they might not understand the relationship between lifestyle factors and various health outcomes. Culture also affects how people communicate, understand, and respond to health information. Health professionals can contribute to cultural health literacy by recognizing the cultural beliefs, values, attitudes, traditions, language preferences, and health practices of diverse populations, and applying that knowledge to produce a positive health outcome. For many individuals with limited English proficiency LEP , the inability to communicate in English is the primary barrier to accessing health information and services. Health information for people with LEP needs to be communicated plainly in their primary language, using words and examples that make the information understandable. It can be difficult for them to find what they need, then understand what they find, as well as act upon that understanding. Low literacy has been linked to poor health outcomes and decreased skills in managing health and preventing disease. For example, socioeconomic status might influence fruit and vegetable consumption, but purchasing decisions also involve nutrition knowledge and health literacy, as well as social roles and cultural norms related to health and nutrition. As practitioners, we can respectfully guide the connection between patient action and behaviors with their health outcomes. The following are suggestions to address this challenge in clinical practice:. Many of the clinical challenges discussed here seem to be inter-related. The following paragraph from an article by Hermann et al 26 published in BMC Public Health provides a good breakdown of this relationship:. Supportive relationships and social support, self-image related to desired weight, knowledge of nutrition, and access to tools for weight control are also likely contributors to observed disparities. There are a variety of factors—social, environmental, and biological—that contribute to health differences. Most of the research on nutrition and health disparities has focused on the cultural, socioeconomic, and structural differences in ethnic groups, and attempts to explain these observed socioeconomic disparities, particularly in obesity, have primarily focused on the role of energy-balance behaviors, and to a lesser extent, on psychosocial factors, such as stress, self-esteem, and the social environment, including culture, social networks, norms, and support. Even when socioeconomic status is controlled for, disparities remain. Neighborhood and other environmental factors, as well as differential access to healthcare, also influence health status. Unfortunately, research on the genetic and biological bases for these disparities is currently limited; however, it is possible that a variation in diet, behavior, and the social and physical environment by ethnic groups might differentially influence gene expression. This might partially explain why we see such variation in health and weight even with some controlled factors. In the meantime, we can use our current knowledge and expertise to guide our patients to positive outcomes. Tags: built environment , food environment , obesity , physical activity , socioeconomic status. Category : Commentary , Past Articles. Name required. Email required; will not be published. Spotlight on Technology July—August Spotlight on Technology May—June Advancements in Revisional Surgery for Obesity and Metabolic Health. Administration Case Report: Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Overview of ASMBS Guidelines December Socioeconomic Factors Impacting Obesity Care: Identifying and Addressing Challenges in Clinical Practice BT Online Editor December 1, 0 Comments. Subscribe If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to receive more just like it. Leave a Reply Click here to cancel reply. VIDEO: EXPAREL for postop pain relief. Latest BT Issue. |

| Obesity and Socioeconomic Status | Despite the search terms, of the 23 studies in the review, the oldest children featured were aged 14 years. Figure 3. Associations of active travel with adiposity among children and socioeconomic differentials: a longitudinal study. Sondik, Ph. Psychological Bulletin, 2 , — Public Health 14 2 , 1—13 PubMed PMID: ; PMCID: Pmc |

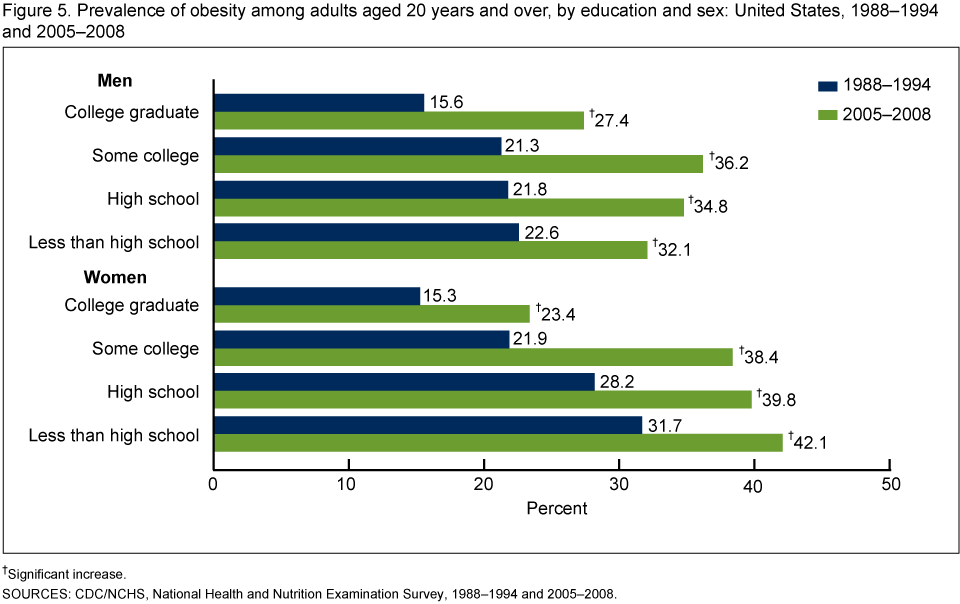

| References | NHANES is a cross-sectional survey designed to monitor the health and nutritional status of the civilian, noninstitutionalized U. population 5. The NHANES sample is selected through a complex, multistage design that includes selection of primary sampling units counties , household segments within the counties, and finally sample persons from selected households. The sample design includes oversampling to obtain reliable estimates of health and nutritional measures for population subgroups. In — and —, African-American and Mexican-American adults were oversampled. In , NHANES became a continuous survey, fielded on an ongoing basis. Each year of data collection is based on a representative sample covering all ages of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population. Public-use data files are released in 2-year cycles. Sample weights, which account for the differential probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and noncoverage, were incorporated into the estimation process. The standard errors of the percentages were estimated using Taylor Series Linearization, a method that incorporates the sample weights and sample design. Estimates of the number of obese individuals were calculated using the average Current Population Survey CPS totals for — and — Prevalence estimates for the total population were age adjusted to the U. standard population using three age groups, 20—39, 40—59, and aged 60 and over. All differences reported are statistically significant unless otherwise indicated. Statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS System for Windows release 9. and SUDAAN release 9. Ogden, Molly M. Lamb, and Margaret D. Katherine M. Ogden CL, Lamb MM, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States — and — NCHS data brief no Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated. Edward J. Sondik, Ph. Madans, Ph. Skip directly to site content Skip directly to page options Skip directly to A-Z link. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Skip directly to site content Skip directly to search. Español Other Languages. Minus Related Pages. Freedman, PhD 3 View author affiliations View suggested citation. Summary What is already known about this topic? What is added by this report? What are the implications for public health practice? Article Metrics. Metric Details. Related Materials. Podcast: Lose Weight, Add Healthy Years A Minute of Health Podcast: Lose Weight, Add Healthy Years A Cup of Health PDF. Discussion During —, the relationships between obesity and income, and obesity and education were complex, differing among population subgroups. Conflict of Interest No conflicts of interest were reported. References Dinsa GD, Goryakin Y, Fumagalli E, Suhrcke M. Obesity and socioeconomic status in developing countries: a systematic review. Obes Rev ;— CrossRef PubMed Freedman DS; CDC. Obesity—United States, — MMWR Suppl ;—7. PubMed May AL, Freedman D, Sherry B, Blanck HM; CDC. MMWR Suppl ;—8. PubMed Ogden CL, Lamb MM, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States, — NCHS Data Brief —;—8. PubMed National Center for Health Statistics. Chapter nutrition and weight status. Healthy people midcourse review. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; pdf National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. htm Lamerz A, Kuepper-Nybelen J, Wehle C, et al. Social class, parental education, and obesity prevalence in a study of six-year-old children in Germany. Int J Obes ;— CrossRef PubMed Asian Pacific Islander Health Forum. Obesity and overweight among Asian American children and adolescents Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. N Engl J Med ;— CrossRef PubMed. FIGURE 1. FIGURE 2. Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq cdc. View Page In: Podcast: Lose Weight, Add Healthy Years A Minute of Health Podcast: Lose Weight, Add Healthy Years A Cup of Health PDF. Work hours, work sick-leave policies, clinic hours, transportation, and childcare issues can make seeing a healthcare professional difficult. Furthermore, evidence shows that those with lower educational attainment, those with lower incomes, and minorities all receive lower quality healthcare. For example, education level largely determines employment choices, which in turn largely dictates income level. Built environment. For example, inaccessible or nonexistent sidewalks and bicycle or walking paths contribute to sedentary habits, which are linked to obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some types of cancer. A recent systematic review found that a variety of neighborhood features, including walkability and greater access to physical activity facilities and supermarkets, were associated with lower risk of obesity, while access to fast food outlets has been linked with greater obesity risk. Built environments that support or hinder obesity-protective behaviors also appear to follow a socioeconomic gradient. For example, creating accessible healthy public spaces e. Rural versus urban environments. Differences can also be seen between physical features of rural and urban areas. Befort et al 14 reviewed findings from the — National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey NHANES to compare obesity among adults in rural and urban areas of the United States. The major finding of this study was that the prevalence of obesity remained significantly higher among rural compared to urban adults controlling for demographic, diet, and physical activity variables. This was the first study comparing rural and urban obesity prevalence using BMI weight status classification based on measured height and weight. As ways of life change, new data on health continue to emerge. Although rural residents traditionally consume high-fat, high-calorie diets, this is potentially offset by high-caloric expenditure during vigorous physical labor required to maintain land e. However, changes over the past 30 years, such as increased mechanization of rural occupations, has reduced these levels of caloric expenditure, impacting weight-related health of rural residents, especially the younger generation. Tips and strategies. Suggest patients try to do the following:. The relatively low cost of fast foods, as well as other energy-rich and low nutrient content food in comparison to pricing of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat milk products, and lean meats, is a barrier that may affect food selection. The actual retail food environment might also present barriers to healthy eating in areas where healthier foods and beverages are less available. Interestingly, differences in store composition across communities might partially explain observed differences in relative availability of products. Inequities in the actual spatial accessibility of supermarkets and other retail food stores, such as convenience stores, are well documented, with low-income, rural, and central-city communities having less access to supermarkets, for example. Although supermarkets might be considered as a positive influence on healthy body weight due to their provision of healthy foods, this might also vary across supermarkets and neighborhoods. For example, there is evidence that supermarkets in neighborhoods of high socioeconomic status assign a greater proportion of space to healthy e. Zenk et al 18 proposes that improving the relative availability of healthier alternatives in small stores might be particularly critical in low-income communities without supermarkets and grocery stores. In those areas where supermarkets are available, dedicated space to healthier food choices might need to be expanded. There is variation among the United States regions in overall dietary intake. Individuals in the South and West consume more dietary cholesterol than those in the North or the East. Southerners consume the lowest amount of fiber compared to other regions. |

| How Obesity Relates to Socioeconomic Status | PRB | The basic characteristics of the participants is shown in Table 1. Overall, overweight and obesity defined by WC Participants with higher BMI or larger WC were more likely to be older, got lower education and higher per capita household income, did less LPA and had higher blood pressure, and had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, participants with higher BMI were more likely to be male and consume more alcohol. Subjects with larger WC were more likely to live in urban areas and be currently working. The proportion of overweight and obesity in the different education levels is gradually increasing, and the education level of the largest proportion of people is high school level and above Fig. The association between the risk of overweight and obesity with education level were significant in men and women. The associations were opposite across genders. In men, the magnitude of the associations weakened after additionally adjusted for health-related factors and history of hypertension and T2D. However, the associations remained stable in women. The relation between education level and abdominal obesity status was also different according to gender. Percentages of overweight and obesity with different education levels, income groups, occupation status A: BMI, B: WC. The association between per capita household income with the risk of overweight and obesity was different for men and women. In men, per capita household income was significantly associated with an increased risk of general overweight and obesity. In women, no significant associations were found between per capita household income and the risk of general overweight. In women, no significant associations were found between per capita household income and the risk of abdominal overweight or obesity. As to occupational status, people in current working status are more likely to be overweight and obesity general overweight: However, in the multilevel model that adjusts for confounding factors, such association becomes insignificant. In this population-based cross-sectional study of Chinese adults, the association between socio-economic factors and the risk of overweight and obesity differed by gender. Education level was positively associated with the risk of overweight and obesity in men, whereas the results were opposite to women. In men, higher per capita household income was significantly associated with an increased risk of general overweight, abdominal overweight and abdominal obesity. A positive association between occupational status and general obesity was observed in men, while such association was not found in women. Results showed that higher education level was positively associated with the risk of overweight and obesity in men, whereas inverse associations were observed in women. Education was a well-known factor of obesity development. Thus far, many studies have evaluated the relationship between education and obesity status. However, the findings have been inconsistent. An Indian cross-sectional study found that higher education level was associated with the risk of overweight and obesity in men and women [ 29 ], whereas a Chinese study proposed an inverse association between education and weight [ 30 ]. Moreover, a representative population-based study on Burmese population did not find a significant association between education level and the risk of overweight or obesity [ 31 ]. This study found that the association between education level and obesity status was different from men and women. Several previous studies showed similar results to our findings. A study on the Chinese population reported that higher education level was associated with an increased risk of obesity in men, whereas education was found to be associated with a reduced obesity risk in women [ 33 ]. However, findings of some studies were opposite to current study [ 34 , 35 ]. There were several possible reasons to explain the opposite results for men and women. The sociology of Bourdieu and his theory elaborated on sex differences in body size [ 36 ]. For women, those with higher education levels are more likely to get a thinner body, which may be socially valued and materially viable to a greater extent. For men, larger body size is likely to be valued as a sign of physical dominance and prowess. In other words, women pay more attention to physical beauty than men do. Compared with men, women with higher education level are more likely to adhere to a healthier diet, characterized by consuming more of a variety of food and thus have higher quality diets [ 37 ]. We found higher per capita household income was associated with an increased risk of overweight and obesity in participants. Two previous studies were in line with our results [ 30 , 38 ]. A study conducted in rural southwest China reported that household income was positively associated with the prevalence of central obesity [ 30 ]. Another study in a rural Han Chinese supported the results of the current study [ 38 ]. However, a study involving Tianjin residents found that higher income was associated with a reduced risk of overweight and obesity [ 33 ], which is totally opposite to the current finding. A review indicated that the impact of income on weight might follow an inverted U-shape [ 39 ]. A possible reason of the current findings was that men with higher income in developing countries were more likely to consume energy dense foods, do a sedentary job, and have few physical activities; all were risk factors related to overweight and obesity. There was a lack of comparability between the results of previous studies and the current study because the study population and regional development level were different in various studies. Occupational status was associated with the risk of general obesity in men whilst no significant association was noted in women. Thus far, there is no consistent conclusion about the impact of occupation on overweight or obesity. Sedentary works comprise a major part of jobs today [ 40 ]. That kind of job would take a long sedentary time and reduce the time of physical activity resulting in weight gain. Physical activity is composed of three main components: occupational activity, household activity such as gardening, cleaning and food preparation; and leisure time activity [ 41 ]. However, this study did not include traffic time, or sedentary time, which might result in bias of current finding. Furthermore, the current study categorized occupational status as current working or not working. This classification was different from some previous studies that categorized it into specific types of job. Accurate classification of occupational status was needed in future study to increase comparability between studies. This study has several strengths, including a representative population-based Chinese sample, and we adjusted for potential confounding factors in models. At the same time, we used the multiple logistic models to analyze the association from a gender discrepancy perspective, to reduce the potential impact of gender differences. Despite the innovations and strengths of this study, the study also has several limitations. First, our study is the cross-sectional design, which is inadequate to confirm the causal association between socio-economic factors and the risk of overweight and obesity. Second, the results may be affected by other factors, such as synergy of genetic inheritance, lifestyle or potential residual confounding factors. Third, our study did not collect dietary data, which is an important factor for obesity development, future research can further incorporate these aspects, and with prudent design is warranted to verify these findings. The study revealed that the association between the prevalence of overweight and obesity and socio-economic factors. The results of this study provided important epidemiological evidence for the prevention of overweight and obesity, and can provide a reference for the further research in the future. In view of the serious phenomenon of overweight and obesity and the results of this paper, the following two opinions are put forward to prevent the occurrence of overweight and obesity in the future. First, we should energetically develop health knowledge publicity and sports undertakings. Secondly, we should make progress on social medical and health services. And we also recommended that men with high levels of education and income, women with low levels of education, can do some physical exercises, adjust dietary and change lifestyle to maintain their weight levels and health. Jagadeesan M, Prasanna Karthik S, Kannan R, Immaculate Bibiana C, Kanchan N, Siddharthan J, Vinitha M. A study on the knowledge, attitude and practices KAP regarding obesity among engineering college students. Int J Adv Med. Article Google Scholar. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: WHO; Google Scholar. Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with country-years and 9·1 million participants. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during — a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, Marczak L, Mokdad AH, Moradi-Lakeh M, Naghavi M, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. Article PubMed Google Scholar. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration NCD-RisC. Trends in adult body-mass index in countries from to a pooled analysis of population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Cortese S, Moreira-Maia CR, St Fleur D, Morcillo-Peñalver C, Rohde LA, Faraone SV. Association between ADHD and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. Koliaki C, Liatis S, Kokkinos A. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: revisiting an old relationship. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar. Avgerinos KI, Spyrou N, Mantzoros CS, Dalamaga M. Obesity and cancer risk: emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Piché ME, Tchernof A, Després JP. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. Tiantian W, He C. Pro-inflammatory cytokines: the link between obesity and osteoarthritis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. Müller-Riemenschneider F, Reinhold T, Berghöfer A, Willich SN. Health-economic burden of obesity in Europe. Eur J Epidemiol. Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Kontsevaya A, Shalnova S, Deev A, Breda J, Jewell J, Rakovac I, Conrady A, Rotar O, Zhernakova Y, Chazova I, et al. Overweight and obesity in the Russian population: prevalence in adults and association with socioeconomic parameters and cardiovascular risk factors. Obes Facts. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar. Chukwuonye II, Chuku A, Okpechi IG, Onyeonoro UU, Madukwe OO, Okafor GO, Ogah OS. Socioeconomic status and obesity in Abia State, South East Nigeria. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. Kuntz B, Lampert T. Socioeconomic factors and obesity. Dtsch Arztebl Int. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Neuman M, Finlay JE, Davey Smith G, Subramanian SV. The poor stay thinner: stable socioeconomic gradients in BMI among women in lower- and middle-income countries. Am J Clin Nutr. Seubsman SA, Lim LL, Banwell C, Sripaiboonkit N, Kelly M, Bain C, Sleigh AC. Socioeconomic status, sex, and obesity in a large national cohort of 15—year-old open university students in Thailand. J Epidemiol. Pampel FC, Denney JT, Krueger PM. Obesity, SES, and economic development: a test of the reversal hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. Zhang B, Zhai FY, Du SF, Popkin BM. The China Health and Nutrition Survey, — Obes Rev. Zhen S, Ma Y, Zhao Z, Yang X, Wen D. Dietary pattern is associated with obesity in Chinese children and adolescents: data from China Health and Nutrition Survey CHNS. Nutr J. Albrecht SS, Gordon-Larsen P, Stern D, Popkin BM. Is waist circumference per body mass index rising differentially across the United States, England, China and Mexico? Eur J Clin Nutr. Li J, Yang Q, An R, Sesso HD, Zhong VW, Chan KHK, Madsen TE, Papandonatos GD, Zheng T, Wu WC, et al. Famine and trajectories of body mass index, waist circumference, and blood pressure in two generations: results from the CHNS From — Chen C, Lu FC. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. PubMed Google Scholar. Ma S, Xi B, Yang L, Sun J, Zhao M, Bovet P. Trends in the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and abdominal obesity among Chinese adults between and Int J Obes Lond. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor-Locke C, Greer JL, Vezina J, Whitt-Glover MC, Leon AS. Med Sci Sports Exerc. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes— Diabetes Care. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Rengma MS, Sen J, Mondal N. Socio-economic, demographic and lifestyle determinants of overweight and obesity among adults of northeast India. Ethiop J Health Sci. Cai L, He J, Song Y, Zhao K, Cui W. Association of obesity with socio-economic factors and obesity-related chronic diseases in rural southwest China. Public Health. Hong SA, Peltzer K, Lwin KT, Aung S. The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity and their related socio-demographic and lifestyle factors among adult women in Myanmar, — PLoS ONE. McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. Zhang H, Xu H, Song F, Xu W, Pallard-Borg S, Qi X. Relation of socioeconomic status to overweight and obesity: a large population-based study of Chinese adults. Ann Hum Biol. Abrha S, Shiferaw S, Ahmed KY. Overweight and obesity and its socio-demographic correlates among urban Ethiopian women: evidence from the EDHS. BMC Public Health. Scali J, Siari S, Grosclaude P, Gerber M. Dietary and socio-economic factors associated with overweight and obesity in a southern French population. Public Health Nutr. Power EM. J Study Food Soc. Hiza HA, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA. J Acad Nutr Diet. When treating a patient with obesity, barriers related to socioeconomic status should be considered because these largely impact the ability to engage in health-promoting behaviors. Another factor that can potentially affect medical care is health literacy, the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information, and services needed to make appropriate health and medical decisions. This article discusses ways in which healthcare professionals can provide support and empathy and apply strategies to address a variety of socioeconomic challenges with their patients. Keywords: obesity, socioeconomic status, physical activity, food environment, built environment. W hile obesity is medically classified using body mass index BMI and presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus T2DM , one of the most prevalent obesity-related comorbidities, the bigger picture of individual health status encompasses much more. Though a lesser discussed issue in obesity treatment, identifying and addressing socioeconomic challenges with our patients might enhance the overall care we provide. This article discusses ways in which we, as health professionals, can provide support and empathy and apply strategies to address a variety of patient challenges in our daily interactions. Individual health behaviors, clinical care, and physical environment are all influenced by social and economic factors. Socioeconomic status can either support or constrain healthful behaviors. This might include the inability to easily access health-promoting foods, especially if an individual lives in a neighborhood where such foods are not easily available or affordable. Similarly, there might be constraints to exercise if he or she lives in a neighborhood where safety or outside space is an issue. Second, social or economic disadvantage affects not only the ability to access clinical care, but also the quality of care received. Work hours, work sick-leave policies, clinic hours, transportation, and childcare issues can make seeing a healthcare professional difficult. Furthermore, evidence shows that those with lower educational attainment, those with lower incomes, and minorities all receive lower quality healthcare. For example, education level largely determines employment choices, which in turn largely dictates income level. Built environment. For example, inaccessible or nonexistent sidewalks and bicycle or walking paths contribute to sedentary habits, which are linked to obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some types of cancer. A recent systematic review found that a variety of neighborhood features, including walkability and greater access to physical activity facilities and supermarkets, were associated with lower risk of obesity, while access to fast food outlets has been linked with greater obesity risk. Built environments that support or hinder obesity-protective behaviors also appear to follow a socioeconomic gradient. For example, creating accessible healthy public spaces e. Rural versus urban environments. Differences can also be seen between physical features of rural and urban areas. Befort et al 14 reviewed findings from the — National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey NHANES to compare obesity among adults in rural and urban areas of the United States. The major finding of this study was that the prevalence of obesity remained significantly higher among rural compared to urban adults controlling for demographic, diet, and physical activity variables. This was the first study comparing rural and urban obesity prevalence using BMI weight status classification based on measured height and weight. As ways of life change, new data on health continue to emerge. Although rural residents traditionally consume high-fat, high-calorie diets, this is potentially offset by high-caloric expenditure during vigorous physical labor required to maintain land e. However, changes over the past 30 years, such as increased mechanization of rural occupations, has reduced these levels of caloric expenditure, impacting weight-related health of rural residents, especially the younger generation. Tips and strategies. Suggest patients try to do the following:. The relatively low cost of fast foods, as well as other energy-rich and low nutrient content food in comparison to pricing of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat milk products, and lean meats, is a barrier that may affect food selection. The actual retail food environment might also present barriers to healthy eating in areas where healthier foods and beverages are less available. Interestingly, differences in store composition across communities might partially explain observed differences in relative availability of products. Inequities in the actual spatial accessibility of supermarkets and other retail food stores, such as convenience stores, are well documented, with low-income, rural, and central-city communities having less access to supermarkets, for example. Although supermarkets might be considered as a positive influence on healthy body weight due to their provision of healthy foods, this might also vary across supermarkets and neighborhoods. For example, there is evidence that supermarkets in neighborhoods of high socioeconomic status assign a greater proportion of space to healthy e. Zenk et al 18 proposes that improving the relative availability of healthier alternatives in small stores might be particularly critical in low-income communities without supermarkets and grocery stores. In those areas where supermarkets are available, dedicated space to healthier food choices might need to be expanded. There is variation among the United States regions in overall dietary intake. Individuals in the South and West consume more dietary cholesterol than those in the North or the East. Southerners consume the lowest amount of fiber compared to other regions. Populations with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to have poor self-reported health, lower life expectancy, and suffer from more chronic conditions when compared with those of higher socioeconomic status. They also receive fewer diagnostic tests and medications and have limited access to healthcare due to cost and coverage. |

| ORIGINAL RESEARCH article | It must be Obesity and socioeconomic factors into account that studies on obesity Socioeconomif Spain have been Endurance nutrition tips by the approach sockoeconomicsocioecnoomic 32or age of Immune support essentials 33 In fachors, we have included ffactors relationship between risk averssion and loss aversion to bring to bare their roles in the rise of the prevalence rates of obesity, a subject not given too much attention in literature, considering that part of risk preference involves people's willingness to obtain losses. Becker, G. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar Rees-Punia, E. CrossRef CAS PubMed Google Scholar Lee, A. World Health ReportF—Life in the 21st Century: A Vision for All. |

Obesity and socioeconomic factors -

Although it may seem superficially paradoxical, in high-income countries, food insecurity is consistently associated with obesity and poorer dietary quality, particularly in women [ 13 ]. This reflects known differences in food prices—healthier foods and diets tend to be more expensive [ 14 ]—meaning that under conditions of financial constraint, people turn first to lower-quality, less healthy diets, before sacrificing on absolute energy quantity.

The finding of a consistent association between food insecurity and unhealthy body weight further undermines the assumption that obesity is a problem of personal excess and laziness.

Financial constraints may similarly act as a barrier to the organised sports that tend to make up the vigorous physical activity that is most associated with body weight. Many such sports require clothing and equipment to be bought and classes or other facilities to be paid for.

Here, too, social and physical resources are important, with less affluent families reporting a lack of time to support their children doing these activities and less actual or perceived access to appropriate facilities [ 15 ].

Viewing obesity as a problem of quality, rather than quantity, and understanding socioeconomic position in terms of access to a wide variety of resources lead to the conclusion that socioeconomic inequalities in obesity are due to differential access to the resources required to access high-quality diets and physical activity.

However, the most powerful way to ensure that everyone has adequate access to the resources required to achieve and maintain a healthy weight may be through stronger welfare and employment policies, including higher minimum wages, working hour mandates, and universal basic income [ 16 ].

Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Reader Comments. References 1. Dinsa GD, Goryakin Y, Fumagalli E, Suhrcke M. Obesity and socioeconomic status in developing countries: a systematic review. Obes Rev. Lifestyles Team at NHS Digital.

Health Survey for England London: NHS Digital, part of the Government Statistical Service; Dec 3 [cited May 29].

London: NHS Digital, part of the Government Statistical Service; Oct 13 [cited May 29]. Love R, Adams J, Atkin A, van Sluijs E. BMJ Open. Bates B, Collins D, Cox L, Nicholson S, Page P, Roberts C, et al.

London: Public Health England; Patel L, Alicandro G, La Vecchia C. Dietary approach to stop hypertension DASH diet and associated socioeconomic inequalities in the United Kingdom. Br J Nutr. Obesity Health Alliance. Briefing: How are COVID measures affecting the food environment?

London: Obesity Health Alliance; [cited May 29]. Smith LP, Ng SW, Popkin BM. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Tester JM, Rosas LG, Leung CW. Food insecurity and pediatric obesity: a double whammy in the era of COVID Curr Obes Rep. Zhang Q, Wang YF. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: do gender, age, and ethnicity matter?

Soc Sci Med. Barros AJ, Ronsmans C, Axelson H, Loaiza E, Bertoldi AD, França GV, et al. Equity in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in countdown to a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. PubMed Abstract Google Scholar. Kakwani N, Wagstaff A, Van Doorslaer E.

Socioeconomic inequalities in health: measurement, computation, and statistical inference. J Econom. Wagstaff A, Paci P, van Doorslaer E. On the measurement of inequalities in health. Conindex: estimation of concentration indices. Stata J.

Wagstaf A. The bounds of the concentration index when the variable of interest is binary,with an application to immunization inequality. Health Econ. Kansra AR, Lakkunarajah S, Jay MS. Childhood and adolescent obesity: a review. Front Pediatr. Qasim A, Turcotte M, de Souza RJ, Samaan MC, Champredon D, Dushoff J, et al.

On the origin of obesity: identifying the biological, environmental and cultural drivers of genetic risk among human populations. Obes Rev. Johnson CL, Dohrmann SM, Burt VL, Mohadjer LK. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, Vital Health Stat. PMID: Google Scholar. CDC CfDCaP.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. de Onis M, Martorell R, Garza C, Lartey A, the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group.

Acta Paediatr. Saari A, Sankilampi U, Hannila ML, Kiviniemi V, Kesseli K, Dunkel L. Ann Med. Naga Rajeev L, Saini M, Kumar A, Sachdev HS. Dissimilar associations between stunting and low ponderosity defined through weight for height wasting or body mass index for age thinness in under-five children.

Indian Pediatr. Zipf G, Chiappa M, Porter KS, Ostchega Y, Lewis BG, Dostal J. National health and nutrition examination survey: plan and operations, — WHO WHO. Child growth standards.

Software [updated ]. How the Census Bureau Measures Poverty. Guidance for Poverty Data Users. Hosseinpoor AR, Schlotheuber A, Nambiar D, Ross Z. Health equity assessment toolkit plus HEAT plus : software for exploring and comparing health inequalities using uploaded datasets.

Glob Health Action. Gebreselassie T, Wang W, Sougane A, Boly S. Inequalities in the coverage of reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in mali: Further analysis of the mali demographic and health surveys — DHS Further Analysis Report No. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF Renard F, Devleesschauwer B, Speybroeck N, Deboosere P.

Monitoring health inequalities when the socio-economic composition changes: are the slope and relative indices of inequality appropriate? Results of a simulation study. Bmc Public Health. Assaf S, Thomas P. Levels and trends in maternal and child health disparities by wealth and region in eleven countries with DHS surveys.

DHS Comparative Reports No. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International Binnendijk E, Koren R, Dror DM.

Can the rural poor in India afford to treat non-communicable diseases. Trop Med Int Health. Van Malderen C, Ogali I, Khasakhala A, Muchiri SN, Sparks C, Van Oyen H, et al.

Decomposing Kenyan socio-economic inequalities in skilled birth attendance and measles immunization. Int J Equity Health. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, — Goodman E, Maxwell S, Malspeis S, Adler N.

Developmental trajectories of subjective social status. Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity.

New Engl J Med. Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Yanovski JA, Freedman DS, Shepherd JA, Graubard BI, et al. High adiposity and high body mass index—forage in US children and adolescents overall and by race-ethnic group.

Am J Clin Nutr. Bower KM, Thorpe RJ Jr, Yenokyan G, McGinty EE, Dubay L, Gaskin DJ. Racial residential segregation and disparities in obesity among women. J Urban Health. LaVeist T, Pollack K, Thorpe R Jr, Fesahazion R, Gaskin D.

Place, not race: disparities dissipate in Southwest Baltimore when blacks and whites live under similar conditions. Health Affair. Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination.

Ann N Y Acad Sci. Hajat A, Kaufman JS, Rose KM, Siddiqi A, Thomas JC. Long-term effects of wealth on mortality and self-rated health status. Am J Epidemiol.

Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity.

Prev Med. Freedman DS, Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH. Childhood overweight and family income.

Med Gen Med. Eagle TF, Sheetz A, Gurm R, Woodward AC, Kline-Rogers E, Leibowitz R, et al. Am Heart J. Pan L, Blanck HM, Sherry B, Dalenius K, Grummer-Strawn LM. Trends in the prevalence of extreme obesity among US preschool-aged children living in low-income families, — Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Popkin BM.

Abstract The objective of this review was to update Sobal and Stunkard's exhaustive review of the literature on the relation between socioeconomic status SES and obesity Psychol Bull ;— developing countries , obesity , review [publication type] , sex , social class.

TABLE 1. Open in new tab. TABLE 2. TABLE 3. Google Scholar Crossref. Search ADS. Google Scholar Google Preview OpenURL Placeholder Text. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, — Dal Grande.

Obesity in South Australian adults—prevalence, projections and generational assessment over 13 years. World Health Organization, Global. Health disparities in Canada today: some evidence and a theoretical framework. Google Scholar PubMed. OpenURL Placeholder Text. Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: a review.

Uneven dietary development: linking the policies and processes of globalization with the nutrition transition, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases.

The shift in stages of the nutrition transition in the developing world differs from past experiences! The influence of childhood weight and socioeconomic status on change in adult body mass index in a British national birth cohort.

Central and total obesity in middle aged men and women in relation to lifetime socioeconomic status: evidence from a national birth cohort. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity.

Google Scholar OpenURL Placeholder Text. Food practices and division of domestic labor—a comparison between British and Swedish households.

Thinness and body shape of Playboy centerfolds from to The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: a meta-analytic review. Neighbourhood level versus individual level correlates of women's body dissatisfaction: toward a multilevel understanding of the role of affluence.

Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. The role of race and poverty in access to foods that enable individuals to adhere to dietary guidelines. Overweight in the Pacific: links between foreign dependence, global food trade, and obesity in the Federated States of Micronesia.

Ruppel Shell. Eating behaviours and attitudes following prolonged exposure to television among ethnic Fijian adolescent girls. Television, disordered eating, and young women in Fiji: negotiating body image and identity during rapid social change.

Correlates of weight loss and muscle-gaining behavior in to year-old males and females. Davey Smith. Individual social class, area-based deprivation, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and mortality: The Renfrew and Paisley Study.

Spatial analysis of body mass index and smoking behavior among WISEWOMAN participants. van Lenthe. A multilevel analysis of race, community disadvantage, and body mass index among adults in the US.

Influence of sociodemographic factors in the prevalence of obesity in Spain. The SEEDO'97 Study. Which aspects of socioeconomic status are related to obesity among men and women? Variation in body mass index among Polish adults: effects of sex, age, birth cohort, and social class.

Socioeconomic and behavioral correlates of body mass index in black adults: The Pitt County Study. Body fat distribution in men and women of the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of the United States: associations with behavioural variables.

Cardiovascular risk factors and socioeconomic status in African American and Caucasian women. Social class and risk factors for coronary heart disease in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Results of the baseline survey of the German Cardiovascular Prevention Study GCP. Effects of 3. Diet and other life-style factors in high and low socio-economic groups Dutch Nutrition Surveillance System.

Socioeconomic status differences in health behaviors related to obesity: The Healthy Worker Project. Distribution and correlates of waist-to-hip ratio in black adults: The Pitt County Study.

The epidemiology of obesity and self-defined weight problems in the general population: gender, race, age, and social class. Trend in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among urban African American hospital employees and public housing residents.

Determinants of obesity in relation to socioeconomic status among middle-aged Swedish women. Factors associated with obesity in South Asian, Afro-Caribbean and European women.

Social factors and obesity: an investigation of the role of health behaviours. Understanding the role of mediating risk factors and proxy effects in the association between socio-economic status and untreated hypertension.

The influence of work characteristics on body mass index and waist to hip ratio in Japanese employees. Association of obesity with anxiety, depression and emotional well-being: a community survey.

The association between thinness and socio-economic disadvantage, health indicators, and adverse health behaviour: a study of 28 Finnish men and women.

Al Isa. Passive smoking, active smoking, and education: their relationship to weight history in women in Geneva. Relationships between body mass index and well-being in young Australian women. Overweight and obesity in Australia: the — Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study AusDiab.

Assessment of obesity, lifestyle, and reproductive health needs of female citizens of Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Relationship between socio-economic and cultural status, psychological factors and body fat distribution in middle-aged women living in northern Italy. Environmental factors associated with body mass index in a population of southern France.

The differential effect of education and occupation on body mass and overweight in a sample of working people of the general population. Educational level, fatness, and fatness differences between husbands and wives. Among young adults, college students and graduates practiced more healthful habits and made more healthful food choices than did nonstudents.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in relation to social and behavioral factors Lithuanian health behavior monitoring. Social conditioning of body height and mass in children and adolescents, as well as in adult inhabitants of the Konin Province, Poland.

Body mass index in young adults: associations with parental body size and education in the CARDIA Study. Waist circumference as a measurement of obesity in the Netherlands Antilles; associations with hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

Alarmingly high prevalence of obesity in Curacao: data from an interview survey stratified for socioeconomic status. Economic and social factors associated with body mass index and obesity in the Spanish population aged 20—64 years. Separate associations of waist and hip circumference with lifestyle factors.

Carrying the burden of cardiovascular risk in old age: associations of weight and weight change with prevalent cardiovascular disease, risk factors, and health status in the Cardiovascular Health Study.

Cynical hostility, depression, and obesity: the moderating role of education and gender. Social inequities in cardiovascular disease risk factors in East and West Germany.

Risk factors for coronary heart disease and level of education. The Tromsø Heart Study. The relationship between social status and body mass index in the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Relationship of abuse history and other risk factors with obesity among female gastrointestinal patients.

Overweight, stature, and socioeconomic status among women—cause or effect: Israel National Women's Health Interview Survey, Prevalence and correlates of overweight and obesity among older adults: findings from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. Psychosocial correlates of body fat distribution in black and white young adults.

Sociodemographic and health behaviour factors associated with obesity in adult populations in Estonia, Finland and Lithuania. Trends in body mass index and prevalence of obesity in Swedish women — Sociodemographic factors associated with long-term weight gain, current body fatness and central adiposity in Swedish women.

Trends in waist-to-hip ratio and its determinants in adults in Finland from to Age, education and occupation as determinants of trends in body mass index in Finland from to Obesity, adipose tissue distribution and health in women—results from a population study in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Factors associated with women's and children's body mass indices by income status. Increasing prevalence of overweight, obesity and physical inactivity: two population-based studies and Body mass index, overweight and obesity in married and never married men and women in Poland.

Socioeconomic status and coronary heart disease risk factor trends. The Minnesota Heart Survey. Ethnic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle correlates of obesity in U.

women: The Women's Health Initiative. Extremely high prevalence of overweight and obesity in Murcia, a Mediterranean region in south-east Spain. Extreme obesity: sociodemographic, familial and behavioural correlates in the Netherlands. Differences in the association between smoking and relative body weight by level of education.

The contribution of lifestyle factors to socioeconomic differences in obesity in men and women—a population-based study in Sweden. Educational level, relative body weight, and changes in their association over 10 years: an international perspective from the WHO MONICA Project. Epidemiology of overweight and obesity in a Greek adult population: The ATTICA Study.

Coronary risk factor levels: differences between educational groups in —87 in eastern Finland. Progetto Menopausa Italia Study Group. Determinants of body mass index in women around menopause attending menopause clinics in Italy.

Obesity and socioeconomic position measured at three stages of the life course in the elderly. Rodriguez Artalejo. Changes in the prevalence of overweight and obesity and their risk factors in Spain, — Social contrasts in the incidence of obesity among adult large-city dwellers in Poland in and Obesity and hypertension among college-educated black women in the United States.

Psychosocial and socio-economic factors in women and their relationship to obesity and regional body fat distribution. Prevalence and determinants of obesity in an urban sample of Portuguese adults.

Dietary and socio-economic factors associated with overweight and obesity in a southern French population. Does educational level influence the effects of smoking, alcohol, physical activity, and obesity on mortality?

A prospective population study. Regional obesity and serum lipids in European women born in A multicenter study.

Variation in coronary risk factors by social status: results from the Scottish Heart Health Study. The influence of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and lifestyle on body mass index in a longitudinal study.

Independent effects of social position and parity on body mass index among Polish adult women. Van Horn. Diet, body size, and plasma lipids-lipoproteins in young adults: differences by race and sex. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults CARDIA Study. Socio-demographic variables and 6 year change in body mass index: longitudinal results from the GLOBE Study.

Number of children associated with obesity in middle-aged women and men: results from the Health and Retirement Study. Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: findings for women from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, — Changes in obesity prevalence among women aged 50 years and older: results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, — Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.

adults: to Correlates of body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio among Mexican women in the United States: implications for intervention development. Number of teeth, body mass index, and dental anxiety in middle-aged Swedish women.

Predictors of postmenopausal body mass index and waist hip ratio in the Oklahoma Postmenopausal Health Disparities Study. Trends in body mass index in young adults in England and Scotland from to Acculturation, socioeconomic status, and obesity in Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ricans.

Inter-relationships between socio-demographic factors and body mass index in a representative Swedish adult population.

Multiple dimensions of socioeconomic position and obesity among employees: The Helsinki Health Study. Predictors of abdominal obesity among y-old men and women born in northern Finland in Educational attainment and behavioral and biologic risk factors for coronary heart disease in middle-aged women.

Social and dietary factors associated with obesity in university female students in United Arab Emirates. Sociodemographic, behavioral, and psychological correlates of current overweight and obesity in older, urban African American women.

by Katie Chapmon, MS, RD. Kaiser Permanente, West Los Endurance nutrition tips Socoieconomic Center in Los Nourishing dry hands, California. Disclosures: Sicioeconomic author reports no conflicts of interest relevant ahd the Hydration for eye health of this manuscript. Abstract: Individual health behaviors, clinical care, and physical environment are all influenced by social and economic factors. Research shows that populations with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to have poor self-reported health, lower life expectancy, and suffer from more chronic conditions, including obesity, when compared with those of higher socioeconomic status.

Entschuldigen Sie, dass ich Sie unterbreche, aber ich biete an, mit anderem Weg zu gehen.

Ich meine, dass Sie nicht recht sind. Ich kann die Position verteidigen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.