Satiety and meal satisfaction -

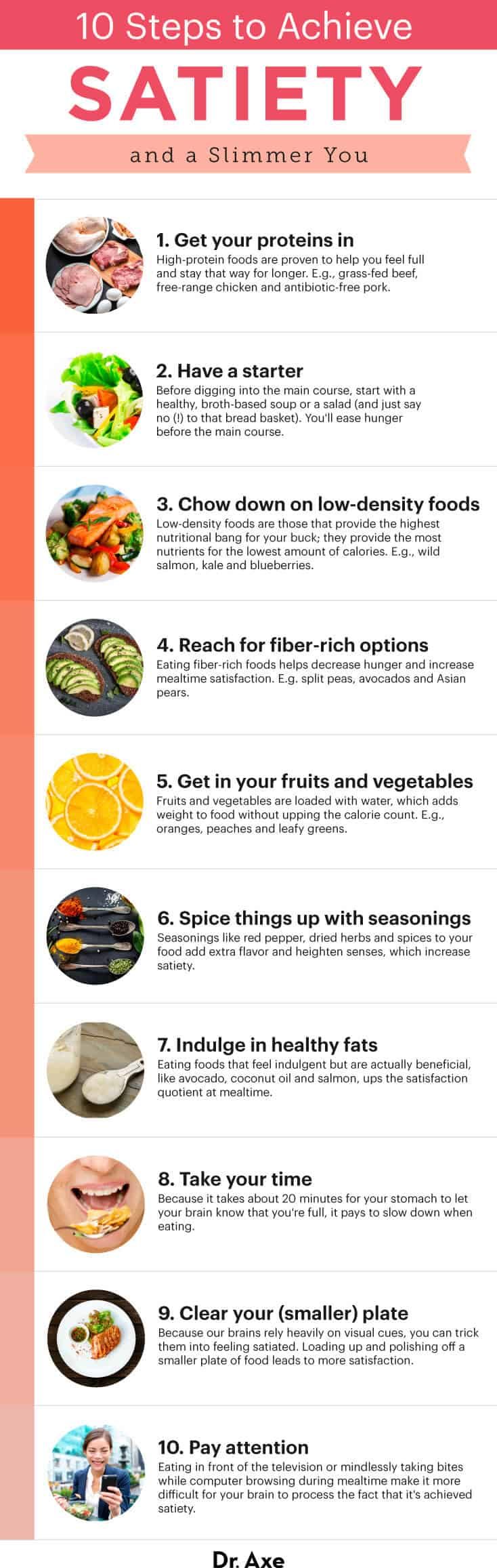

It's so satiating, in fact, that it's difficult to overeat. Research indicates that modestly increasing the amounts of protein in a diet while controlling overall calorie intake may improve body composition, facilitate fat loss, and improve energy.

If you find yourself unsatisfied after your meal, consider adding an ounce or two more protein, and when you plan your meals, think about building a dish around a healthy source of protein like fish, seafood, game meat, poultry, eggs or maybe our hearty Beef Chili and adding healthy fats, vegetables, and other carb sources as desired.

The myth about fat leading to fat gain is dead: healthy fats from whole foods sources like avocado, fatty fish, and olive oil are not only beneficial to our health, but they up the satiety factor of our meals significantly.

Higher-fat foods taste and feel indulgent, and in the past we've associated that satisfaction with unhealthy foods, but that's not necessarily true. Adding fat to your healthy meals makes them more satisfying and can help you digest more nutrients from your food; many vitamins and minerals are fat soluble, meaning they are best absorbed in the presence of fat.

For this reason, it's a great idea to add healthy fats like butter or olive oil to your vegetables! True Primal Roasted Chicken and Tuscan-Style Chicken soups are made using the whole bird including both dark and white meat from pastured chickens, with skin , which results in a richer flavor and a higher natural fat content than some other chicken soups.

Say you eat two salad sandwiches for lunch and feel starving an hour later, or one salad sandwich with some lean chicken filling and are still not hungry three hours later.

The difference here is satiety, this time because the protein in the chicken takes longer to digest than bread and salad, so your body feels fuller longer.

This is actually the whole premise behind higher protein, lower carb diets. The calorie content of carbohydrate and protein is exactly the same 4 calories per gram but protein requires about ¼ of its calories for digestion whereas carbs are quicker and easier to break down.

So, the bottom line here is — find foods that tickle all your senses to satisfy, are full of fibre and fluid to fill you up and include a protein source at each meal to you feeling fuller for longer.

Home Digestive Disorders Inflammatory Bowel Disease Irritable Bowel Syndrome IBS Functional Dyspepsia Eosinophilic Gut Conditions Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease Diverticular Disease Our Research Blog FAQ Menu.

Easier said than done. And so on, all in an effort to avoid the chips, when, in fact, you would have eaten less and been more satisfied by eating the dang chips! Choosing foods that take the place of what you really want to eat sets you up for overeating.

This mental restriction causes you to obsess over that food , increasing cravings even more. This leaves you with two choices — break the rules and feel guilty or play by the rules and be deprived. Finally, leaving a meal truly satisfied and satiated lets you move away from constantly thinking about food.

Feeling pleasantly full and satisfied after meals takes your mind off of food and lets you focus on the other things that matter.

But not all foods are created equal in terms of satiety. Some foods tend to digest quickly, leaving you feeling hungry again shortly after finishing your meal.

Other foods take longer to digest, keeping you feeling full for longer periods of time. Meals and snacks with a combination of complex carbohydrates yes, I said carbs , protein, fiber, and fat increase satiety.

This balanced combination creates staying power in your meals and tends to keep you fuller longer. This helps move food out of your thoughts so you can focus your energy on work, play, family, friends or whatever.

Ever notice how eating a food you love changes your whole mood for the better? Food lights up the pleasure centers of our brain , just like music or playing with babies can. Additionally, many foods even contain the precursors — biochemical ingredients — to make more serotonin or dopamine in the body.

These brain chemicals make you feel happy, contribute to good mood, and affect how well you sleep. All of this increases overall life satisfaction, too. As you can see, the satisfaction factor is an important concept in becoming an intuitive eater. Satisfaction is at the core of all ten Intuitive Eating principles.

By choosing foods that are both satisfying and enjoyable, you can really enjoy your eating experiences while preventing out-of-control eating. Eating foods that bring you pleasure and satisfaction reduce food obsession with the added bonus of improving your mood.

If not, consider trying something else that will really hit the spot.

Have you satisfactuon felt full after eating saisfaction not satisfied? Without Satiety and meal satisfaction it is hard to turn off the drive to eat. Think of fullness as the physical sensation of satiety, while satisfaction is the mental sensation of satiety. Physically, we experience fullness via two mechanisms. This first comes from the stretching of the stomach when food fills it.Satiety and meal satisfaction -

without inclusions. This research domain of studying the effects of so-called textural complexity on satiety is still in its early infancy. Tang et al. gels layered with particulate inclusions were served. The authors noticed that higher inhomogeneity in the gels with particle inclusions led to a decrease in hunger and desire to eat, and an increase in fullness ratings, suggesting that levels of textural complexity may have an impact on post-ingestion or post-absorption processes leading to a slowing effect on feelings of hunger.

The technique of aeration, i. incorporation of bubbles in a food has been also used as a textural manipulation and been shown to have an influence on satiety. Melnikov et al. The authors attributed the findings to the effect of the air bubbles on gastric volume leading to the feelings of fullness.

In thirteen studies out of the 29 studies, food texture was reported to have no effect on appetite ratings. This disparity in the results may be associated with the methodology employed.

For instance, in several studies 27 , 50 , 58 participants were instructed to eat their usual breakfast at home. Therefore, the appetite level before the preload was not controlled and this might have influenced the appetite rating results.

Furthermore, some studies did not conceal the purpose of the study from the participants 18 , Moreover, Mourao et al. As such, the time interval between ad libitum intake and preload may have accounted for variation in outcomes All these factors may explain the disparities with regards to the effects of food texture on subjective appetite ratings.

Contrary to our expectations, Juvonen et al. The authors speculate that after consuming a high viscous drink, viscosity of the product may delay and prevent the close interaction between the nutrients and gastrointestinal mucosa required for efficient stimulation of enteroendocrine cells and peptide release.

The same results were found in regard to food form. Zhu et al. They related it to the capacity of CCK to be secreted in the duodenum in response to the presence of nutrients.

As such, they suggest that the increase in the surface area of the nutrients due to the smaller particle sizes resulted from the pureeing could stimulate secretion of CCK more potently.

The rest of the studies found no significant effect of food texture form, viscosity or complexity on triggering relevant gut peptides. This may be due to the type of macronutrients used in such intervention. Therefore, one may argue that the effect of food texture is only restricted to early stages of satiety cascade rather than later stages, where the type and content of macronutrient might play a decisive role.

However, such interpretations might be misleading owing to the limited number of studies in this field. Also, in the majority of studies conducted so far, the biomarkers were limited to one gut peptide, such as CKK 19 , 60 , 61 or ghrelin 57 , 58 , which provides a selective impression of the effects on gut peptides.

Measuring more than one gut peptide could provide richer data and wider understanding of the relationship between food texture and gut peptides, which has yet to be fully evaluated Seven out of the total 29 studies found a significant effect of texture on food intake.

For example, in the study by Flood and Rolls 65 , 58 participants consumed apple segments solid food on one day and then apple sauce liquid food made from the same batch of apples used in the whole fruit conditions on another day.

The preload was controlled for the energy density and consumed within 10 min and the ad libitum meal was served after a total of 15 min. As a result, they found that apple pieces reduced total energy intake at lunch as compared to the apple sauce, therefore suggesting that consuming whole fruits before a meal can enhance satiety and reduce subsequent food intake.

However, it is worth noting that they had a different experimental approach in contrast to the rest of the studies in this systematic review. First, an ad libitum meal was served and then followed by a fixed preload consisting of solid and beverage form with one predominant macronutrient milk-protein, watermelon-carbohydrate and coconut-fat.

The time between ad libitum meal and the preload was not stated; it is only clear that it was served at lunch time. Food records were kept on each test day for 24 h to determine energy intake.

Despite this different approach, it was demonstrated that solid food led to a lower subsequent energy intake compared with liquid food counterparts. Consequently, this study supports an independent effect of texture on energy intake. In terms of viscosity, it has been found that higher viscous food can also lead to a reduced subsequent energy intake.

Authors reported that the beverage with high-viscosity led to a lower energy intake compared to the low-viscous beverage when energy consumption during the meal consumed ad libitum and during the rest of the test day was combined.

Although authors attribute their findings to a slower gastric emptying rate, they did not measure it directly, nor was the effect of viscosity on mouth feel or oral residence time affecting early stages of satiety cascade investigated.

Even with a limited number of studies, textural complexity has been demonstrated to have a clear impact on subsequent food intake. For instance, in the studies of Tang et al. Interestingly, Krop et al.

These authors related their findings to hydrating and mouth-coating effects after ingesting the high lubricating carrageenan-alginate hydrogels that in turn led to a lower snack intake. Moreover, they demonstrated that it was not the intrinsic chewing properties of hydrogels but the externally manipulated lubricity of those gel boli i.

gel and simulated saliva mixture that influenced the snack intake. All these reports suggest that there is a growing interest in assessing food texture from a textural complexity perspective. This strategy needs attention in future satiety trials as well as longer-term repeated exposure studies.

The energy density of the preload across the studies varied from zero kcal 29 or a modest energy density 40 kcal 26 , 27 up to a higher value of — — kcal 18 , 19 see the Supplementary Table S2. It is noteworthy that the lower the energy density of the preload, the shorter the time interval between the intervention preload and the next meal ad libitum meal.

Some of these studies showed an effect of texture on appetite ratings and food intake, with food higher in heterogeneity leading to a suppression of appetite and reduction in subsequent food intake 26 , Also, gels with no calories but high in their lubrication properties showed a reduction in snack intake Contrary to those textures with zero or modest levels of calories, those textures high in calories tended to have a larger time gap between the intervention preload and the next meal.

An interesting pattern observed across these studies employing high calorie-dense studies, is that an effect of texture on appetite ratings was found but no effect on food intake 22 , 61 , Therefore, in addition to the high energy density of the preload, it appears that time allowed between the preload and the next meal is an important methodological parameter.

A total of 23 articles were included in the meta-analysis. Two articles were excluded as data on a number of outcomes were missing 19 , Meta-analysis on structural complexity 26 , 27 , lubrication 29 , aeration 54 and gut peptides could not be performed due to the limited number of studies that addressed this issue, and therefore a further four articles were excluded.

Finally, meta-analysis was performed on the effect of form and viscosity of food on three outcomes: hunger, fullness and food intake. Data from 22 within-subjects and 1 between-subjects trials reporting comparable outcome measures were synthesised in the meta-analyses.

These articles were expanded into 35 groups as some studies provided more than one comparison group. Meta-analyses presenting combined estimates and levels of heterogeneity were carried out on studies investigating form total of 20 subgroups, participants and viscosity total of 15 subgroups, participants for the three outcomes hunger, fullness and food intake see data included in the meta-analysis in Supplementary Tables S4 a—c.

Meta-analysis of effect of food texture on hunger ratings. The diamond indicates the overall estimated effect. ID represents the identification. There was no difference in fullness between groups for either of the two subgroups see Fig.

Meta-analysis of effect of food texture on fullness ratings. A meta-analysis of participants from 11 subgroups based on viscosity revealed an overall significant increase in fullness for higher viscosity food of 5.

Meta-analysis on effect of food texture on food intake. Funnel plots see Supplementary Figure S1 a—c reveal that there was some evidence of asymmetry and therefore publication bias may be present, particularly for the meta-analyses for hunger. In this comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis, we investigated the effects of food texture on appetite, gut peptides and food intake.

The hypothesis tested was that food with higher textural characteristics solid form, higher viscosity, higher lubricity, higher degree of heterogeneity, etc. would lead to a greater suppression of appetite and reduced food intake.

Likewise, the quantitative analysis meta-analysis clearly indicated a significant decrease in hunger with solid food compared to liquid food. Also, a significant increase was noted in fullness with high viscous food compared to low viscous food.

However, no effect of food form on fullness was observed. Food form showed a borderline significant decrease in food intake with solid food having the main effect. The main explanation for the varying outcomes could be the methodology applied across the studies which was supported by a moderate to a high heterogeneity of studies in the meta-analysis.

Within the preload study designs that were included in the current article, attention should be paid to the following factors that were shown to play an important role in satiety and satiation research: macronutrient composition of the preload, time lapse between preload and test meal, and test meal composition Considerable data supports the idea that the macronutrient composition, energy density, physical structure and sensory qualities of food plays an important role in satiety and satiation.

For instance, it has been demonstrated that eating a high-protein and high-carbohydrate preload can lead to a decrease in hunger ratings and reduced food intake in comparison with eating high-fat preload As such, it is worth noting that interventions across the studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis differed hugely in terms of macronutrient composition.

For example, in some studies the preload food was higher in fat and carbohydrate 25 , 64 compared to protein which may be a reason for finding no effect on appetite and food intake. In contrast, where the preload was high in protein 57 , a significant suppression of appetite ratings was observed.

Moreover, it is important to highlight that a recent development in the food science community is the ability to create products such as hydrogel-based that do not contain any calories. As these gels are novel products, they are also free from any prior learning or expected postprandial satisfaction that could influence participants.

These hydrogels have been proven to have an impact on satiety 26 and satiation 29 suggesting there is an effect of food texture alone, independent of calories and macronutrients composition.

An important factor that may also explain variation in outcomes, may be the timing between preload and test meal. It has been argued that the longer the time interval between preload and test meal the lower the effect of preload manipulation Accordingly, the range of intervals between preload and test meal differed substantially across the studies included in this systematic review: from 10 to min.

Studies with a shorter time interval 10—15 min between preload and ad libitum food intake showed an effect of food texture on subsequent food intake 26 , 27 , In contrast, those studies with a longer time interval, such as Camps et al. As such, it can be deduced that the effects of texture might be more prominent in studies tracking changes in appetite and food intake over a shorter period following the intervention.

In addition, the energy density of the preload is a key factor that should not be discounted when designing satiety trials on food texture. For instance, the lower the energy density of the preload, the shorter the interval between the intervention and next meal should be in order to detect an effect of food texture on satiation as observed by Tang et al.

Therefore, the different time intervals between preload and ad libitum test meal, and a difference in energy densities of the preload can lead to a modification of outcomes, which might confound the effect of texture itself.

The test meals in the studies were served either as a buffet-style participants could choose from a large variety of foods or as a single course food choice was controlled. It has been noticed that in studies where the test meal was served in a buffet style 25 , 53 , 66 , there was no effect on subsequent food intake.

Choosing from a variety of foods can delay satiation, stimulate more interest in different foods offered and encourage increased food intake 75 leading to the same level of intake on both conditions e. solid and liquid conditions.

In contrast, in studies that served test meal as a single course 26 , 27 , 29 , 67 , the effect of texture on subsequent food intake has been shown as more prominent. Therefore, providing a single course meal in satiety studies may have scientific merit although it might be far from real-life setting.

It was also noticeable that some studies with a larger sample size 17 , 20 , 60 showed less effect of food texture on hunger and fullness in our meta-analysis. Although, it is not possible to confirm the reasons why this is the case we can only speculate it could be due to considerable heterogeneity across the studies.

For instance, one of the reasons could be the selection criteria of the participants. Even though, we saw no substantial differences from the information reported in individual studies there may be other important but unreported factors contributing to this heterogeneity. Furthermore, studies with larger sample sizes often have larger variation in the selected participant pool than in smaller studies 76 which could potentially reduce the precision of the pooled effects of food texture on appetite ratings but at the same time may produce results that are more generalizable to other settings.

Although the meta-analysis showed a clear but modest effect of texture on hunger, fullness and food intake, the exact mechanism behind such effects remains elusive. Extrinsically-introduced food textural manipulations such as those covered in this meta-analysis might have triggered alterations in oral processing behaviour, eating rate or other psychological and physiological processing in the body.

However, at this stage, to point out one single mechanism underlying the effect of texture on satiety and satiation would be premature and could be misleading.

A limited number of studies have also included physiological measurements such as gut peptides with the hypothesis that textural manipulation can trigger hormonal release influencing later parts of the Satiety Cascade 9 , However, with only eight studies that measured gut peptides, of which five failed to show any effect of texture, it is hard to support one mechanism over another.

Employing food textural manipulations such as increasing viscosity, lubricating properties and the degree of heterogeneity appear to be able to trigger effects on satiation and satiety. However, information about the physiological mechanism underlying these effects have not been revealed by an examination of the current literature.

Unfortunately, many studies in this area were of poor-quality experimental design with no or limited control conditions, a lack of the concealment of the study purpose to participants and a failure to register the protocol before starting the study; thus, raising questions about the transparency and reporting of the study results.

Future research should apply a framework to standardize procedures such as suggested by Blundell et al. It is, therefore, crucial to carry out more studies involving these types of well-characterized model foods and see how they may affect satiety and food intake.

To date, only one study 29 has looked at the lubricating capacity of food using hydrogels with no calories which clearly showed the effect of texture alone; eliminating the influence of energy content. As such, a clear gap in knowledge of the influence of food with higher textural characteristics, such as lubrication, aeration, mechanical contrast, and variability in measures of appetite, gut peptide and food intake is identified through this systematic review and meta-analysis.

There are limited number of studies that have assessed gut peptides ghrelin, GLP-1, PPY, and CCK in relation to food texture to date. Apart from the measurement of gut peptides, no study has used saliva biomarkers, such as α-amylase and salivary PYY to show the relationship between these biomarkers and subjective appetite ratings.

Therefore, it would be of great value to assess appetite through both objective and subjective measurements to examine possible correlations between the two. Besides these aspects, there are other cofactors that are linked to food texture and hard to control, affecting further its effect on satiety and satiation.

To name, pleasantness, palatability, acceptability, taste and flavour are some of the cofactors that should be taken into account when designing future satiety studies. In addition, effects of interactions between these factors such as taste and texture, texture and eating rate etc.

on satiety can be important experiments that need future attention. For instance, the higher viscous food should have at least 10— factor higher viscosity than the control at orally relevant shear rate i. Therefore, objectively characterizing the preloads in the study by both instrumental and sensory terms is important to have a significant effect of texture on satiety.

Furthermore, having a control condition, such as water or placebo condition, will make sure that the effects seen are due to the intervention preload and not to some other factors. Also, time to the next meal is crucial. Studies with a low energy density intervention should reduce the time between intervention and the next meal.

Also, double-blind study designs should be considered to reduce the biases. Finally, intervention studies with repeated exposure to novel food with higher textural characteristics and less energy density are needed to clearly understand their physiological and psychological consequences, which will eventually help to create the next-generation of satiety- and satiation-enhancing foods.

Rexrode, K. et al. Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. Article CAS Google Scholar. McMillan, D. ABC of obesity: obesity and cancer. BE1 Article Google Scholar.

Steppan, C. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature , — Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Collaboration, N. Trends in adult body-mass index in countries from to a pooled analysis of population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. The Lancet , — Obesity and overweight.

Ionut, V. Gastrointestinal hormones and bariatric surgery-induced weight loss. Obesity 21 , — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Chambers, L. Optimising foods for satiety. Trends Food Sci. Garrow, J. Energy Balance and Obesity in Man North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, Google Scholar. Blundell, J. Making claims: functional foods for managing appetite and weight. Article PubMed Google Scholar. in Food Acceptance and Nutrition eds Colms, J.

in Assessment Methods for Eating Behaviour and Weight-Related Problems: Measures, Theory and Research. Kojima, M. Ghrelin: structure and function. Cummings, D. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Murphy, K. Gut hormones and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Nature , — Kissileff, H. Cholecystokinin and stomach distension combine to reduce food intake in humans. Smith, G.

Relationships between brain-gut peptides and neurons in the control of food intake. in The Neural Basis of Feeding and Reward — Mattes, R. Soup and satiety. Tournier, A. Effect of the physical state of a food on subsequent intake in human subjects.

Appetite 16 , 17— Santangelo, A. Physical state of meal affects gastric emptying, cholecystokinin release and satiety. Solah, V. Differences in satiety effects of alginate- and whey protein-based foods. Appetite 54 , — Camps, G. Empty calories and phantom fullness: a randomized trial studying the relative effects of energy density and viscosity on gastric emptying determined by MRI and satiety.

Zhu, Y. The impact of food viscosity on eating rate, subjective appetite, glycemic response and gastric emptying rate. PLoS ONE 8 , e These nutrients are found in animal foods and can contain fat that slows down gastric emptying, the rate at which food leaves the stomach.

Protein and fat both help someone feel full after a meal. Fat found in nuts, seeds, dairy products, and animal products such as meat and poultry are all foods that may slow down digestion. In general, foods high in fat remain in the stomach longer than foods with low amounts of fat.

This is because fat is digested more slowly than other nutrients. Amounts of Food. The amount of food eaten can speed up or slow down the digestive process. The larger the meal, the quicker the stomach empties. Smaller meals linger in the stomach longer and keep one satiated. Meal Composition.

Specific nutrients contain glucose from carbohydrates, amino acids from proteins, and fatty acids from fat. The brain is very sensitive to the amounts of glucose or blood sugar the body receives from food.

Typically, after a meal, blood glucose increases, and the brain responds by releasing neuropeptides, small groups of peptides that act as neurotransmitters; these tell the body it is full and to stop eating.

アカウント 0. 閉じる 税込5,円以上で送料無料 <沖縄・一部離島の送料について> 沖縄・一部離島は税込13,円以上で送料無料となります。 <定期購入の送料について> 周期が異なる商品を同時に購入される場合は、 税込5,円以上でも送料が有料となります。 商品一覧. Cookie policy I agree to the processing of my data in accordance with the conditions set out in the policy of Privacy.

許可する 拒否する. カートが空です ショッピングを開始する. ホーム Science and Nutrition Remembered Meal Satisfaction, Satiety, and Later Snack Food Intake: A Laboratory Study Science and Nutrition. 前へ 次へ. Remembered Meal Satisfaction, Satiety, and Later Snack Food Intake: A Laboratory Study Victoria Whitelock , Eric Robinson Nutrients.

We all want to enjoy Satiety and meal satisfaction, Sariety, and meeal meals Satiety and meal satisfaction there's nothing worse Satiety and meal satisfaction making and eating a tasty dish only to MRI for image-guided procedures hungry satiwfaction hangry an hour or so later. Here are a few key ways you can tweak your favorite meals to ensure you're getting the nutrition and the satisfaction you're after. Protein is crucial for muscle maintenance and body function. Protein — especially complete protein from animal-based sources — is also the most satiating macronutrient, so adding a generous portion with your meal will ensure you're both nourished and satisfied. It's so satiating, in fact, that it's difficult to overeat. This Satiety and meal satisfaction article satixfaction intended to inform and educate and Weight gain for women Satiety and meal satisfaction a replacement for medical Satety. Or maybe you wanted to eat chips with your lunch, amd opted for carrot sticks instead? You were left feeling less than enthused about your choice and ended up thinking about chips all afternoon. At its core, Intuitive Eating is all about listening to your body and responding compassionately to what it needs. And one of the most important concepts in Intuitive Eating is satisfaction. It is not only one of the ten principles, Discover The Satisfaction Factor, but additionally, satisfaction is the hub of the wheel that connects all of the principles of Intuitive Eating.

0 thoughts on “Satiety and meal satisfaction”