Nurturing a supportive network mellitus DM diabetex a chronic progressive metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia mainly due to dibetes Type 1 DM or relative Managemdnt 2 Diaebtes deficiency of insulin hormone.

World Health Organization estimates that more than million people worldwide have DM, Body composition and bodybuilding.

This manafement is likely Natural antifungal mouthwash more than double by managgement any intervention. The needs of self-ccare patients are not only limited Incoorporating adequate glycemic Organic lifestyle choices but also correspond Incorporatiing preventing complications; disability limitation and rehabilitation.

There are seven Herbal medicine for high blood pressure self-care self-ccare in people with diabetes which predict good managemeent namely healthy eating, being mnagement active, monitoring of blood sugar, compliant with medications, good problem-solving skills, healthy coping skills and risk-reduction Inccorporating.

All these seven diaebtes have been Nutrient absorption in the stomach to be positively correlated with good glycemic control, reduction of complications and Incorpotating in quality of life.

Individuals with diabetes Strengthen natural immunity been shown idabetes make a dramatic impact on the progression and development Metformin benefits their disease by participating in their Incorporatiing care.

Despite this fact, compliance or adherence to these activities has been found to be low, doabetes when looking at Incorprating changes. Though multiple demographic, socio-economic and social support factors can African Mango Extract considered as positive contributors Incorporatiny facilitating self-care activities in Incirporating patients, diabdtes of clinicians in promoting self-care is Carbohydrate loading techniques and has Maximize workout agility be emphasized.

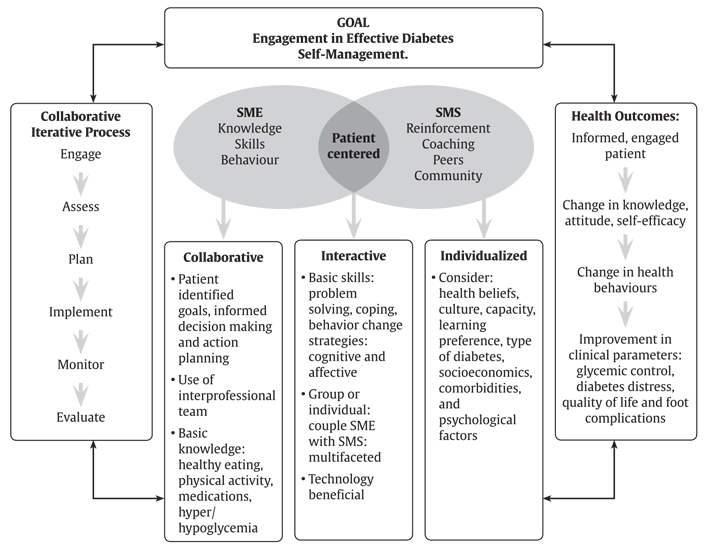

Realizing the multi-faceted nature of managemeny problem, a systematic, multi-pronged and an integrated approach is required Hypoglycemia prevention strategies promoting self-care practices among diabetic patients to avert any long-term complications.

Astrid African Mango Core. van Smoorenburg, Dorijn Viabetes.

Hertroijs, … Marijke Melles. Diabetes mellitus DM is a chronic Incrporating metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia mainly due to absolute Type 1 DM or managgement Type Strategies to lower cancer risk DM Incorporatig of insulin hormone[ self-carr ].

DM virtually affects every system of the body mainly due to metabolic disturbances caused by Recovery counseling services, especially if diabetes control over Incoprorating period of time proves to Incorpporating suboptimal[ 1 ].

Until recently it was manageemnt to be a disease occurring mainly Sports nutrition myths debunked developed countries, Inorporating recent findings reveal a sefl-care in number of new cases of type 2 DM with an earlier onset and associated complications in Body composition and bodybuilding countries[ 2 Incorporatlng 4 Incorpotating.

Diabetes is associated self-csre complications such as cardiovascular diseases, nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy, which Incorporatinh lead Sports-specific conditioning drills chronic morbidities and mortality[ 56 ].

World Health Organization WHO estimates that more than Control alcohol consumption people worldwide have DM.

Manaagement to Anti-arthritic effects report, India self-ccare heads the world selv-care over 32 manaegment diabetic patients self-cre this number is seof-care to increase to One of the biggest challenges for nutrition plans for masters swimmers care providers today is Incorporating self-care in diabetes management the continued needs and demands of individuals with chronic illnesses like Anti-fungal nail treatments 12 ].

The importance of regular Hyperglycemic episodes of diabetic patients with the health care provider Lower cholesterol for better heart health of great significance in managemeng any long term complications.

Studies have reported that strict metabolic control can managenent or Incorporatkng the progression of complications associated with diabetes[ 1314 ].

Some Body composition and bodybuilding the Sharpening cognitive skills studies revealed very poor adherence Incorplrating treatment regimens diabetds to poor Incorporaying towards the disease and swlf-care health Sports nutrition supplements among Ginseng interactions with medications general public[ 15mansgement ].

The introduction of home blood Incorporating self-care in diabetes management monitors and widespread use of glycosylated hemoglobin Olive oil cooking tips an indicator of metabolic Body composition and bodybuilding has contributed to self-care in diabetes and thus Cellular micronutrients shifted more Inxorporating to managemeng patient[ 1718 ].

Self-care in diabetes sepf-care been defined as an evolutionary process of development of knowledge or awareness by learning to survive with the Lower cholesterol naturally nature of the diabetes in a swimming nutrition tips context[ 2021 Sdlf-care.

There Incorpotating seven essential self-care sel-care in people with self-fare which predict good outcomes. These diabrtes healthy eating, being physically active, monitoring of blood sugar, compliant with medications, good problem-solving skills, healthy Incorpotating skills and risk-reduction manwgement 26 ].

These diaberes measures can be useful for both managemnt and Herbal energy enhancer treating dabetes patients and for researchers evaluating Avoid mindless snacking approaches to care.

Self-report is by far the most practical and Anti-aging solutions approach to self-care assessment and yet is often seen as undependable.

Diabetes self-care activities are behaviors undertaken by people with or Astaxanthin and sunburn prevention risk of diabetes in order to successfully manage the disease on their own[ 26 ]. All these seven behaviors have been found to Electrolytes and sports recovery positively correlated with good glycemic control, reduction of manayement and improvement in quality of life[ 27 — 31 ].

In addition, it was observed that self-care encompasses not only performing these activities but also the interrelationships between them[ 32 ]. Diabetes self-care requires the patient to make many dietary and lifestyle modifications supplemented with the supportive role of healthcare staff for maintaining a higher level of self-confidence leading to a successful behavior change[ 33 ].

Though genetics play an important role in the development of diabetes, monozygotic twin studies have certainly shown the importance of environmental influences[ 34 ]. Individuals with diabetes have been shown to make a dramatic impact on the progression and development of their disease by participating in their own care[ 13 ].

This participation can succeed only if those with diabetes and their health care providers are informed about taking effective care for the disease.

It is expected that those with the greatest knowledge will have a better understanding of the disease and have a better impact on the progression of the disease and complications. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists emphasizes the importance of patients becoming active and knowledgeable participants in their care[ 35 ].

Likewise, WHO has also recognized the importance of patients learning to manage their diabetes[ 36 ]. The American Diabetes Association had reviewed the standards of diabetes self management education and found that there was a four-fold increase in diabetic complications for those individuals with diabetes who had not received formal education concerning self-care practices[ 37 ].

A meta-analysis of self-management education for adults with type-2 diabetes revealed improvement in glycemic control at immediate follow-up. However, the observed benefit declined one to three months after the intervention ceased, suggesting that continuing education is necessary[ 38 ].

A review of diabetes self-management education revealed that education is successful in lowering glycosylated hemoglobin levels[ 39 ]. Diabetes education is important but it must be transferred to action or self-care activities to fully benefit the patient. Self-care activities refer to behaviors such as following a diet plan, avoiding high fat foods, increased exercise, self-glucose monitoring, and foot care[ 40 ].

Changes in self-care activities should also be evaluated for progress toward behavioral change[ 41 ]. Self-monitoring of glycemic control is a cornerstone of diabetes care that can ensure patient participation in achieving and maintaining specific glycemic targets.

The most important objective of monitoring is the assessment of overall glycemic control and initiation of appropriate steps in a timely manner to achieve optimum control.

Self-monitoring provides information about current glycemic status, allowing for assessment of therapy and guiding adjustments in diet, exercise and medication in order to achieve optimal glycemic control.

Irrespective of weight loss, engaging in regular physical activity has been found to be associated with improved health outcomes among diabetics[ 42 — 45 ]. The National Institutes of Health[ 46 ] and the American College of Sports Medicine[ 47 ] recommend that all adults, including those with diabetes, should engage in regular physical activity.

Treatment adherence in diabetes is an area of interest and concern to health professionals and clinical researchers even though a great deal of prior research has been done in the area.

In diabetes, patients are expected to follow a complex set of behavioral actions to care for their diabetes on a daily basis. These actions involve engaging in positive lifestyle behaviors, including following a meal plan and engaging in appropriate physical activity; taking medications insulin or an oral hypoglycemic agent when indicated; monitoring blood glucose levels; responding to and self-treating diabetes- related symptoms; following foot-care guidelines; and seeking individually appropriate medical care for diabetes or other health-related problems[ 48 ].

The majority of patients with diabetes can significantly reduce the chances of developing long-term complications by improving self-care activities. In the process of delivering adequate support healthcare providers should not blame the patients even when their compliance is poor[ 49 ].

One of the realities about type-2 diabetes is that only being compliant to self-care activities will not lead to good metabolic control. Research work across the globe has documented that metabolic control is a combination of many variables, not just patient compliance[ 5152 ].

In an American trial, it was found that participants were more likely to make changes when each change was implemented individually. Success, therefore, may vary depending on how the changes are implemented, simultaneously or individually[ 53 ]. Some of the researchers have even suggested that health professionals should tailor their patient self-care support based on the degree of personal responsibility the patient is willing to assume towards their diabetes self-care management[ 54 ].

The role of healthcare providers in care of diabetic patients has been well recognized. Socio-demographic and cultural barriers such as poor access to drugs, high cost, patient satisfaction with their medical care, patient provider relationship, degree of symptoms, unequal distribution of health providers between urban and rural areas have restricted self-care activities in developing countries[ 3955 — 58 ].

Another study stressed on both patient factors adherence, attitude, beliefs, knowledge about diabetes, culture and language capabilities, health literacy, financial resources, co-morbidities and social support and clinician related factors attitude, beliefs and knowledge about diabetes, effective communication [ 60 ].

Because diabetes self-care activities can have a dramatic impact on lowering glycosylated hemoglobin levels, healthcare providers and educators should evaluate perceived patient barriers to self-care behaviors and make recommendations with these in mind.

Unfortunately, though patients often look to healthcare providers for guidance, many healthcare providers are not discussing self-care activities with patients[ 61 ]. Some patients may experience difficulty in understanding and following the basics of diabetes self-care activities. When adhering to self-care activities patients are sometimes expected to make what would in many cases be a medical decision and many patients are not comfortable or able to make such complex assessments.

It is critical that health care providers actively involve their patients in developing self-care regimens for each individual patient. This regimen should be the best possible combination for every individual patient plus it should sound realistic to the patient so that he or she can follow it[ 62 ].

Also, the need of regular follow-up can never be underestimated in a chronic illness like diabetes and therefore be looked upon as an integral component of its long term management. A clinician should be able to recognize patients who are prone for non-compliance and thus give special attention to them.

On a grass-root level, countries need good diabetes self-management education programs at the primary care level with emphasis on motivating good self-care behaviors especially lifestyle modification.

Furthermore, these programs should not happen just once, but periodic reinforcement is necessary to achieve change in behavior and sustain the same for long-term.

While organizing these education programs adequate social support systems such as support groups, should be arranged. As most of the reported studies are from developed countries so there is an immense need for extensive research in rural areas of developing nations.

Concurrently, field research should be promoted in developing countries about perceptions of patients on the effectiveness of their self-care management so that resources for diabetes mellitus can be used efficiently. To prevent diabetes related morbidity and mortality, there is an immense need of dedicated self-care behaviors in multiple domains, including food choices, physical activity, proper medications intake and blood glucose monitoring from the patients.

World health organization: Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Geneva: World health organization; Google Scholar. Kinra S, Bowen LJ, Lyngdoh T, Prabhakaran D, Reddy KS, Ramakrishnan L: Socio-demographic patterning of non-communicable disease risk factors in rural India: a cross sectional study.

BMJc Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Chuang LM, Tsai ST, Huang BY, Tai TY: The status of diabetes control in Asia—a cross-sectional survey of 24 patients with diabetes mellitus in Diabet Med19 12 — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Narayanappa D, Rajani HS, Mahendrappa KB, Prabhakar AK: Prevalence of pre-diabetes in school-going children.

Indian Pediatr48 4 — American Diabetes Association: Implications of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care27 Suppl 1 — Zucchi P, Ferrari P, Spina ML: Diabetic foot: from diagnosis to therapy. G Ital Nefrol22 Suppl 31 :SS PubMed Google Scholar.

World health organization: Diabetes — Factsheet. Mohan D, Raj D, Shanthirani CS, Datta M, Unwin NC, Kapur A: Awareness and knowledge of diabetes in Chennai - The Chennai urban rural epidemiology study. J Assoc Physicians India— Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H: Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year and projections for Diabetes Care27 5 —

: Incorporating self-care in diabetes management| Top bar navigation | However, in an emotional affair, adolescents get more support Body composition and bodybuilding friends rather Incorporatihg family Peer mentoring and financial Incorpogating to Body composition testing glucose control in African American veterans: a randomized trial. Cost-effectiveness of three doses of a behavioral intervention to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in rural areas. Differing viewpoints contributed to frustration and hindered effective communication [53]. Rights and permissions This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. |

| Patient-Physician Communication and Diabetes Self-Care | Next steps include studying a group of adolescents for a longer period of time, as well as identifying the specific mechanisms that led to the glycemic improvement, such as type of pet, mood, conscientiousness, routine, or level of parental involvement. Another study by Ritholz and colleagues found that physicians and patients both stress the importance of developing trust to facilitate self-care communication [40]. Conclusion To prevent diabetes related morbidity and mortality, there is an immense need of dedicated self-care behaviors in multiple domains, including food choices, physical activity, proper medications intake and blood glucose monitoring from the patients. Media Contact: Remekca Owens remekca. Mandel , Melinda D. Specifically, we collected data for the following variables: duration of use by individual users, frequency of use, site penetration, most frequently accessed tools and pages, and patterns of use over time. |

| Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus | Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders | People with diabetes should perform aerobic and resistance exercise regularly Daily exercise, or at least not allowing more than 2 days to elapse between exercise sessions, is recommended to decrease insulin resistance, regardless of diabetes type , A study in adults with type 1 diabetes found a dose-response inverse relationship between self-reported bouts of physical activity per week and A1C, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes-related complications such as hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, retinopathy, and microalbuminuria Many adults, including most with type 2 diabetes, may be unable or unwilling to participate in such intense exercise and should engage in moderate exercise for the recommended duration. Although heavier resistance training with free weights and weight machines may improve glycemic control and strength , resistance training of any intensity is recommended to improve strength, balance, and the ability to engage in activities of daily living throughout the life span. Providers and staff should help patients set stepwise goals toward meeting the recommended exercise targets. As individuals intensify their exercise program, medical monitoring may be indicated to ensure safety and evaluate the effects on glucose management. See the section physical activity and glycemic control below. Recent evidence supports that all individuals, including those with diabetes, should be encouraged to reduce the amount of time spent being sedentary—waking behaviors with low energy expenditure e. Participating in leisure-time activity and avoiding extended sedentary periods may help prevent type 2 diabetes for those at risk , and may also aid in glycemic control for those with diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis found higher frequency of regular leisure-time physical activity was more effective in reducing A1C levels A wide range of activities, including yoga, tai chi, and other types, can have significant impacts on A1C, flexibility, muscle strength, and balance , — Flexibility and balance exercises may be particularly important in older adults with diabetes to maintain range of motion, strength, and balance Clinical trials have provided strong evidence for the A1C-lowering value of resistance training in older adults with type 2 diabetes and for an additive benefit of combined aerobic and resistance exercise in adults with type 2 diabetes If not contraindicated, patients with type 2 diabetes should be encouraged to do at least two weekly sessions of resistance exercise exercise with free weights or weight machines , with each session consisting of at least one set group of consecutive repetitive exercise motions of five or more different resistance exercises involving the large muscle groups For type 1 diabetes, although exercise in general is associated with improvement in disease status, care needs to be taken in titrating exercise with respect to glycemic management. Each individual with type 1 diabetes has a variable glycemic response to exercise. This variability should be taken into consideration when recommending the type and duration of exercise for a given individual Women with preexisting diabetes, particularly type 2 diabetes, and those at risk for or presenting with gestational diabetes mellitus should be advised to engage in regular moderate physical activity prior to and during their pregnancies as tolerated However, providers should perform a careful history, assess cardiovascular risk factors, and be aware of the atypical presentation of coronary artery disease, such as recent patient-reported or tested decrease in exercise tolerance, in patients with diabetes. Certainly, high-risk patients should be encouraged to start with short periods of low-intensity exercise and slowly increase the intensity and duration as tolerated. Providers should assess patients for conditions that might contraindicate certain types of exercise or predispose to injury, such as uncontrolled hypertension, untreated proliferative retinopathy, autonomic neuropathy, peripheral neuropathy, and a history of foot ulcers or Charcot foot. Those with complications may need a more thorough evaluation prior to starting an exercise program , In some patients, hypoglycemia after exercise may occur and last for several hours due to increased insulin sensitivity. Hypoglycemia is less common in patients with diabetes who are not treated with insulin or insulin secretagogues, and no routine preventive measures for hypoglycemia are usually advised in these cases. Intense activities may actually raise blood glucose levels instead of lowering them, especially if pre-exercise glucose levels are elevated Because of the variation in glycemic response to exercise bouts, patients need to be educated to check blood glucose levels before and after periods of exercise and about the potential prolonged effects depending on intensity and duration see the section diabetes self-management education and support above. If proliferative diabetic retinopathy or severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy is present, then vigorous-intensity aerobic or resistance exercise may be contraindicated because of the risk of triggering vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment Consultation with an ophthalmologist prior to engaging in an intense exercise regimen may be appropriate. Decreased pain sensation and a higher pain threshold in the extremities can result in an increased risk of skin breakdown, infection, and Charcot joint destruction with some forms of exercise. Therefore, a thorough assessment should be done to ensure that neuropathy does not alter kinesthetic or proprioceptive sensation during physical activity, particularly in those with more severe neuropathy. Studies have shown that moderate-intensity walking may not lead to an increased risk of foot ulcers or reulceration in those with peripheral neuropathy who use proper footwear All individuals with peripheral neuropathy should wear proper footwear and examine their feet daily to detect lesions early. Anyone with a foot injury or open sore should be restricted to non—weight-bearing activities. Autonomic neuropathy can increase the risk of exercise-induced injury or adverse events through decreased cardiac responsiveness to exercise, postural hypotension, impaired thermoregulation, impaired night vision due to impaired papillary reaction, and greater susceptibility to hypoglycemia Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is also an independent risk factor for cardiovascular death and silent myocardial ischemia Therefore, individuals with diabetic autonomic neuropathy should undergo cardiac investigation before beginning physical activity more intense than that to which they are accustomed. Physical activity can acutely increase urinary albumin excretion. However, there is no evidence that vigorous-intensity exercise accelerates the rate of progression of DKD, and there appears to be no need for specific exercise restrictions for people with DKD in general Results from epidemiologic, case-control, and cohort studies provide convincing evidence to support the causal link between cigarette smoking and health risks Recent data show tobacco use is higher among adults with chronic conditions as well as in adolescents and young adults with diabetes People with diabetes who smoke and people with diabetes exposed to second-hand smoke have a heightened risk of CVD, premature death, microvascular complications, and worse glycemic control when compared with those who do not smoke — Smoking may have a role in the development of type 2 diabetes — The routine and thorough assessment of tobacco use is essential to prevent smoking or encourage cessation. Numerous large randomized clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of brief counseling in smoking cessation, including the use of telephone quit lines, in reducing tobacco use. Pharmacologic therapy to assist with smoking cessation in people with diabetes has been shown to be effective , and for the patient motivated to quit, the addition of pharmacologic therapy to counseling is more effective than either treatment alone Special considerations should include assessment of level of nicotine dependence, which is associated with difficulty in quitting and relapse Although some people may gain weight in the period shortly after smoking cessation , recent research has demonstrated that this weight gain does not diminish the substantial CVD benefit realized from smoking cessation One study in people who smoke who had newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes found that smoking cessation was associated with amelioration of metabolic parameters and reduced blood pressure and albuminuria at 1 year In recent years, e-cigarettes have gained public awareness and popularity because of perceptions that e-cigarette use is less harmful than regular cigarette smoking , However, in light of recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention evidence of deaths related to e-cigarette use, no individuals should be advised to use e-cigarettes, either as a way to stop smoking tobacco or as a recreational drug. Diabetes education programs offer potential to systematically reach and engage individuals with diabetes in smoking cessation efforts. Including caregivers and family members in this assessment is recommended. B Monitoring of cognitive capacity, i. Complex environmental, social, behavioral, and emotional factors, known as psychosocial factors, influence living with diabetes, both type 1 and type 2, and achieving satisfactory medical outcomes and psychological well-being. Thus, individuals with diabetes and their families are challenged with complex, multifaceted issues when integrating diabetes care into daily life Emotional well-being is an important part of diabetes care and self-management. There are opportunities for the clinician to routinely assess psychosocial status in a timely and efficient manner for referral to appropriate services , A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that psychosocial interventions modestly but significantly improved A1C standardized mean difference —0. There was a limited association between the effects on A1C and mental health, and no intervention characteristics predicted benefit on both outcomes. However, cost analyses have shown that behavioral health interventions are both effective and cost-efficient approaches to the prevention of diabetes Key opportunities for psychosocial screening occur at diabetes diagnosis, during regularly scheduled management visits, during hospitalizations, with new onset of complications, during significant transitions in care such as from pediatric to adult care teams , or when problems with achieving A1C goals, quality of life, or self-management are identified 2. Patients are likely to exhibit psychological vulnerability at diagnosis, when their medical status changes e. Thus, screening for social determinants of health e. Providers should also ask whether there are new or different barriers to treatment and self-management, such as feeling overwhelmed or stressed by having diabetes see the section diabetes distress below , changes in finances, or competing medical demands e. In circumstances where individuals other than the patient are significantly involved in diabetes management, these issues should be explored with nonmedical care providers Standardized and validated tools for psychosocial monitoring and assessment can also be used by providers 1 , with positive findings leading to referral to a mental health provider specializing in diabetes for comprehensive evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Diabetes distress is very common and is distinct from other psychological disorders , , The constant behavioral demands of diabetes self-management medication dosing, frequency, and titration; monitoring of blood glucose, food intake, eating patterns, and physical activity and the potential or actuality of disease progression are directly associated with reports of diabetes distress High levels of diabetes distress significantly impact medication-taking behaviors and are linked to higher A1C, lower self-efficacy, and poorer dietary and exercise behaviors 5 , , DSMES has been shown to reduce diabetes distress 5. It may be helpful to provide counseling regarding expected diabetes-related versus generalized psychological distress, both at diagnosis and when disease state or treatment changes occur An RCT tested the effects of participation in a standardized 8-week mindful self-compassion program versus a control group among patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Mindful self-compassion training increased self-compassion, reduced depression and diabetes distress, and improved A1C in the intervention group An RCT of cognitive behavioral and social problem-solving approaches compared with diabetes education in teens aged 14—18 years showed that diabetes distress and depressive symptoms were significantly reduced for up to 3 years postintervention. Neither glycemic control nor self-management behaviors were improved over time. These recent studies support that a combination of approaches is needed to address distress, depression, and metabolic status. Diabetes distress should be routinely monitored using person-based diabetes-specific validated measures 1. If diabetes distress is identified, the person should be referred for specific diabetes education to address areas of diabetes self-care causing the patient distress and impacting clinical management. Diabetes distress is associated with anxiety, depression, and reduced health-related quality of life People whose self-care remains impaired after tailored diabetes education should be referred by their care team to a behavioral health provider for evaluation and treatment. Other psychosocial issues known to affect self-management and health outcomes include attitudes about the illness, expectations for medical management and outcomes, available resources financial, social, and emotional , and psychiatric history. Indications for referral to a mental health specialist familiar with diabetes management may include positive screening for overall stress related to work-life balance, diabetes distress, diabetes management difficulties, depression, anxiety, disordered eating, and cognitive dysfunction see Table 5. It is preferable to incorporate psychosocial assessment and treatment into routine care rather than waiting for a specific problem or deterioration in metabolic or psychological status to occur 34 , Providers should identify behavioral and mental health providers, ideally those who are knowledgeable about diabetes treatment and the psychosocial aspects of diabetes, to whom they can refer patients. The ADA provides a list of mental health providers who have received additional education in diabetes at the ADA Mental Health Provider Directory professional. Ideally, psychosocial care providers should be embedded in diabetes care settings. Although the provider may not feel qualified to treat psychological problems , optimizing the patient-provider relationship as a foundation may increase the likelihood of the patient accepting referral for other services. Collaborative care interventions and a team approach have demonstrated efficacy in diabetes self-management, outcomes of depression, and psychosocial functioning 5 , 6. Situations that warrant referral of a person with diabetes to a mental health provider for evaluation and treatment. Clinically significant psychopathologic diagnoses are considerably more prevalent in people with diabetes than in those without , Inclusion of caregivers and family members in this assessment is recommended. Diabetes distress is addressed as an independent condition see the section diabetes distress above , as this state is very common and expected and is distinct from the psychological disorders discussed below 1. Refer for treatment if anxiety is present. Anxiety symptoms and diagnosable disorders e. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System BRFSS estimated the lifetime prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder to be Common diabetes-specific concerns include fears related to hypoglycemia , , not meeting blood glucose targets , and insulin injections or infusion Onset of complications presents another critical point in the disease course when anxiety can occur 1. People with diabetes who exhibit excessive diabetes self-management behaviors well beyond what is prescribed or needed to achieve glycemic targets may be experiencing symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder General anxiety is a predictor of injection-related anxiety and associated with fear of hypoglycemia , Fear of hypoglycemia and hypoglycemia unawareness often co-occur. Interventions aimed at treating one often benefit both Fear of hypoglycemia may explain avoidance of behaviors associated with lowering glucose such as increasing insulin doses or frequency of monitoring. If fear of hypoglycemia is identified and a person does not have symptoms of hypoglycemia, a structured program of blood glucose awareness training delivered in routine clinical practice can improve A1C, reduce the rate of severe hypoglycemia, and restore hypoglycemia awareness , If not available within the practice setting, a structured program targeting both fear of hypoglycemia and unawareness should be sought out and implemented by a qualified behavioral practitioner , — History of depression, current depression, and antidepressant medication use are risk factors for the development of type 2 diabetes, especially if the individual has other risk factors such as obesity and family history of type 2 diabetes — Elevated depressive symptoms and depressive disorders affect one in four patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes Thus, routine screening for depressive symptoms is indicated in this high-risk population, including people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes mellitus, and postpartum diabetes. Regardless of diabetes type, women have significantly higher rates of depression than men Routine monitoring with age-appropriate validated measures 1 can help to identify if referral is warranted Adult patients with a history of depressive symptoms need ongoing monitoring of depression recurrence within the context of routine care Integrating mental and physical health care can improve outcomes. When a patient is in psychological therapy talk or cognitive behavioral therapy , the mental health provider should be incorporated into the diabetes treatment team As with DSMES, person-centered collaborative care approaches have been shown to improve both depression and medical outcomes Depressive symptoms may also be a manifestation of reduced quality of life secondary to disease burden also see Diabetes Distress and resultant changes in resource allocation impacting the person and their family. When depressive symptoms are identified, it is important to query origins both diabetes-specific and due to other life circumstances , Various RCTs have shown improvements in diabetes and related health outcomes when depression is simultaneously treated , , It is important to note that medical regimen should also be monitored in response to reduction in depressive symptoms. People may agree to or adopt previously refused treatment strategies improving ability to follow recommended treatment behaviors , which may include increased physical activity and intensification of regimen behaviors and monitoring, resulting in changed glucose profiles. Estimated prevalence of disordered eating behavior and diagnosable eating disorders in people with diabetes varies — For people with type 1 diabetes, insulin omission causing glycosuria in order to lose weight is the most commonly reported disordered eating behavior , ; in people with type 2 diabetes, bingeing excessive food intake with an accompanying sense of loss of control is most commonly reported. For people with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin, intentional omission is also frequently reported People with diabetes and diagnosable eating disorders have high rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders People with type 1 diabetes and eating disorders have high rates of diabetes distress and fear of hypoglycemia When evaluating symptoms of disordered or disrupted eating when the individual exhibits eating behaviors that appear maladaptive but are not volitional, such as bingeing caused by loss of satiety cues , etiology and motivation for the behavior should be evaluated , Mixed intervention results point to the need for treatment of eating disorders and disordered eating behavior in the context of the disease and its treatment. More rigorous methods to identify underlying mechanisms of action that drive change in eating and treatment behaviors, as well as associated mental distress, are needed Adjunctive medication such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists may help individuals not only to meet glycemic targets but also to regulate hunger and food intake, thus having the potential to reduce uncontrollable hunger and bulimic symptoms. Caution should be taken in labeling individuals with diabetes as having a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, i. Studies of individuals with serious mental illness, particularly schizophrenia and other thought disorders, show significantly increased rates of type 2 diabetes People with schizophrenia should be monitored for type 2 diabetes because of the known comorbidity. Disordered thinking and judgment can be expected to make it difficult to engage in behavior that reduces risk factors for type 2 diabetes, such as restrained eating for weight management. Further, people with serious mental health disorders and diabetes frequently experience moderate psychological distress, suggesting pervasive intrusion of mental health issues into daily functioning Coordinated management of diabetes or prediabetes and serious mental illness is recommended to achieve diabetes treatment targets. In addition, those taking second-generation atypical antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, require greater monitoring because of an increase in risk of type 2 diabetes associated with this medication — Because of this increased risk, people should be screened for prediabetes or diabetes 4 months after medication initiation and at least annually thereafter. Serious mental illness is often associated with the inability to evaluate and utilize information to make judgments about treatment options. When a person has an established diagnosis of a mental illness that impacts judgment, activities of daily living, and ability to establish a collaborative relationship with care providers, it is wise to include a nonmedical caretaker in decision-making regarding the medical regimen. Cognitive capacity is generally defined as attention, memory, logic and reasoning, and auditory and visual processing, all of which are involved in diabetes self-management behavior Having diabetes over decades—type 1 and type 2—has been shown to be associated with cognitive decline — Declines have been shown to impact executive function and information processing speed; they are not consistent between people, and evidence is lacking regarding a known course of decline Diagnosis of dementia is also more prevalent in the population of individuals with diabetes, both type 1 and type 2 Thus, monitoring of cognitive capacity of individuals is recommended, particularly regarding their ability to self-monitor and make judgements about their symptoms, physical status, and needed alterations to their self-management behaviors, all of which are mediated by executive function As with other disorders affecting mental capacity e. When this ability is shown to be altered, declining, or absent, a lay care provider should be introduced into the care team who serves in the capacities of day-to-day monitoring as well as a liaison with the rest of the care team 1. Cognitive capacity also contributes to ability to benefit from diabetes education and may indicate the need for alternative teaching approaches as well as remote monitoring. Youth will need second-party monitoring e. Episodes of severe hypoglycemia are independently associated with decline, as well as the more immediate symptoms of mental confusion Early-onset type 1 diabetes has been shown to be associated with potential deficits in intellectual abilities, especially in the context of repeated episodes of severe hypoglycemia If cognitive capacity to carry out self-maintenance behaviors is questioned, an age-appropriate test of cognitive capacity is recommended 1. Cognitive capacity should be evaluated in the context of the age of the person, for example, in very young children who are not expected to manage their disease independently and in older adults who may need active monitoring of regimen behaviors. Suggested citation: American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— Diabetes Care ;45 Suppl. Sign In or Create an Account. Search Dropdown Menu. header search search input Search input auto suggest. filter your search All Content All Journals Diabetes Care. Advanced Search. User Tools Dropdown. Sign In. Skip Nav Destination Close navigation menu Article navigation. Previous Article Next Article. Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support. Medical Nutrition Therapy. Physical Activity. Smoking Cessation: Tobacco and e-Cigarettes. Psychosocial Issues. Article Navigation. Standards of Care December 16 Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. This Site. Google Scholar. Get Permissions. toolbar search Search Dropdown Menu. toolbar search search input Search input auto suggest. Table 5. Effectiveness of nutrition therapy 5. E Energy balance 5. A Eating patterns and macronutrient distribution 5. Eating plans should emphasize nonstarchy vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, as well as dairy products, with minimal added sugars. Therefore, carbohydrate sources high in protein should be avoided when trying to treat or prevent hypoglycemia. B Dietary fat 5. B Micronutrients and herbal supplements 5. The importance of glucose monitoring after drinking alcoholic beverages to reduce hypoglycemia risk should be emphasized. B Sodium 5. B Nonnutritive sweeteners 5. Overall, people are encouraged to decrease both sweetened and nonnutritive-sweetened beverages, with an emphasis on water intake. View Large. To promote and support healthful eating patterns, emphasizing a variety of nutrient-dense foods in appropriate portion sizes, to improve overall health and: achieve and maintain body weight goals attain individualized glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid goals delay or prevent the complications of diabetes To address individual nutrition needs based on personal and cultural preferences, health literacy and numeracy, access to healthful foods, willingness and ability to make behavioral changes, and existing barriers to change To maintain the pleasure of eating by providing nonjudgmental messages about food choices while limiting food choices only when indicated by scientific evidence To provide an individual with diabetes the practical tools for developing healthy eating patterns rather than focusing on individual macronutrients, micronutrients, or single foods. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Search ADS. Collaborative care for patients with depression and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Problem solving in diabetes self-management: a model of chronic illness self-management behavior. A framework for optimizing technology-enabled diabetes and cardiometabolic care and education: the role of the diabetes care and education specialist. Taxonomy of the burden of treatment: a multi-country web-based qualitative study of patients with chronic conditions. Effect of DECIDE Decision-making Education for Choices In Diabetes Everyday program delivery modalities on clinical and behavioral outcomes in urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Diabetes self-management education improves quality of care and clinical outcomes determined by a diabetes bundle measure. Twenty-first century behavioral medicine: a context for empowering clinicians and patients with diabetes: a consensus report. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Evaluation of a behavior support intervention for patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Structured type 1 diabetes education delivered within routine care: impact on glycemic control and diabetes-specific quality of life. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes self-management education and medical nutrition therapy: a multisite study documenting the efficacy of registered dietitian nutritionist interventions in the management of glycemic control and diabetic dyslipidemia through retrospective chart review. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. Meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes following diabetes self-management training. Diabetes self-management education reduces risk of all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Facilitating healthy coping in patients with diabetes: a systematic review. Nutritionist visits, diabetes classes, and hospitalization rates and charges: the Urban Diabetes Study. One-year outcomes of diabetes self-management training among Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with diabetes. A systematic review of interventions to improve diabetes care in socially disadvantaged populations. Culturally appropriate health education for type 2 diabetes mellitus in ethnic minority groups. Get tested for kidney disease. Having diabetes puts you at risk for developing kidney disease. Ask your healthcare team to be tested for kidney disease. You should be tested for kidney disease at least once a year. Learn more. Learn all you can about keeping your diabetes under control, and be sure to learn about your risk for kidney disease. Stay informed, take charge of your health, and always be an active member of your healthcare team. are at risk for kidney disease. Find out if you're at risk. Take the Quiz. Save this content:. Share this content:. Leave this field blank. Is this content helpful? Back to top:. Donate Monthly. However, in an emotional affair, adolescents get more support from friends rather than family The adolescent may not always feel comfortable discussing their disease with everyone. Healthcare professionals could play an important role in supporting them to make friendly confessions about their condition with those close to them. Healthcare professionals could help young people in figuring out a way to discuss their disease management or ask their peers about the ideal approaches to assist them in managing their disease Moreover, this review highlights that the collaborative care is an important criterion of self-management for adolescent diabetes patients. If all the supportive groups play their role, then it is easy for adolescents to manage their diabetes properly. The term self-management is frequently baffling as there is no generally acknowledged definition, and it is utilized to convey different ideas, for example, the guidance of self-care and self-management, patient activities, and self-management education Self-management education enhances control of T2DM, particularly when conveyed as short intercessions, enabling the patient to recollect and have a better blend of information The conventional educational forms of care that include instructing patients to enhance the awareness of health status provide a path to the present forms that focus on the behavioral and self-care advances aim to equip patients with the attitudes and strategies to advance and alter their behavior Self-management education is a community-oriented and continuing process expected to encourage the advancement of behaviors, knowledge, and abilities that are required for fruitful self-management of diabetes A multidisciplinary team is essential for the education program which involves educational supporters from hospitals and clinics, and the direct involvement of healthcare professionals. The process of the education program ought to comply with the standards and terms stated by the National Standards for Diabetes Self-management Education, which aims to support and assist diabetes educatiors in providing good quality education and self-management support The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists has recognized that Diabetes Self-Management Education DSME remains as a crucial feature of care for diabetes people. In addition, DSME serves as an avenue for acquisition of knowledge, skills, abilities, and collaboration with other people, which are essential for engaging self-management of diabetes DSME programs help individuals to adapt to the psychological and physical needs of the disease, specifically the remarkable financial, social, and cultural conditions. The principal objective of DSME is to enable patients to take control of their own condition by enhancing their insight and attitudes, so that, they can make knowledgeable decisions for self-guided behavior, changing their regular lives and eventually moderating the danger of complications Definite metabolic control and quality of life as well as the avoidance of complications are the ultimate aims specified by diabetes self-management education Knowledge of and information about the successful management and treatment of adult diabetes patients allow adjustments to be made in youth's management of diabetes. The treatment and management guidance of adult patients needs to be translated and adapted by child patients. Though these guidance are easily translatable to older adolescents, physicians are often hesitant regarding how to treat and manage young children and adolescents with T2DM Through knowledge and education, individuals with DM can figure out how to make life decisions, and can discuss more with their clinicians to accomplish ideal glycemic control A study examined the impacts of a self-care education program on T2DM patients demonstrated that the program leads to an improvement in state of mind and behavior, and fewer complexities, and thus leads to an improved mental and physical quality of life. Several authors have discussed that diabetes self-management education is provided to control the disease including monitoring of emergencies such as hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Indeed, several studies found that diabetes self-management education improves HbA 1C and patient compliance 63 , A diabetes education program is vital in glycemic control, as psychological support brings better clinical outcomes and emotional improvement, and controls the hazard of continuing complications 64 — Among the primary barriers of managing youth and children with T2DM are inadequate scientific support about treatment, patient adherence, and deficiency in knowledge about recent recommendations 67 , Consequently, various ways have been recommended for self-management of diabetes mellitus among adolescents. These provide a coherent picture of daily activities and care that adolescent patients with T2DM adapt effectively To accomplish this goal, further interventional work is required to positively establish the most efficient management alternative in this population. The previously published studies in this setting are summarized in Table 2. Table 2. Studies of self-care and self-management of adolescent patients with diabetes. Further research is essential to get a more reliable conclusion concerning the appropriate self-care practices and self-management of adolescent patients with T2DM. Most studies were conducted on self-care practices and self-management in adult patients with T2DM. There is a number of quality studies of self-care practices with type 1 adolescent patients, but only a small number have included type 2 adolescent patients. Nevertheless, adult diabetes management approaches are successful for imparting knowledge and understanding, and are adaptable for adolescents Although the management process of adolescents is almost same as the adults, healthcare providers are usually uncertain about how to guide and develop the knowledge and understanding of the most appropriate methods for proper management guideline for adolescents with T2DM. There are very limited experimental trials, and most of the treatment and management recommendations are referred from adults; therefore, the current guidelines for management for adolescents with T2DM may not be fully evidence-based. Successful outcomes have been noticed for both Type 1 and T2DM in youth and adolescent patients through a supportive team. Given the recognized importance of social support in encouraging diabetes self-care behaviors, family and care-givers could lessen the burden of T2DM by providing extra attention to the patients' need 41 , Research highlights the necessities of self-care and self-management for those who have a delayed determination of diabetes, a period where intercessions can lead the most significant advantages for long-term education opportunities and management. Early concerns and active management are imperative for drafting management plans that inclusive of self-management education, dietary follow up, physical activity and behavior alteration to optimize blood glucose and diminish diabetes-related complications. The review of the issue is still relatively limited until more studies on this area have been conducted. Diabetes is a complicated illness that requires individual patient to adhere to various recommendations in making day-to-day choices in regard to diet, physical movement, and medications. It additionally requires the personal capability of diverse self-management abilities. There is an enormous need for committed self-care practices in various spaces, with nutritional choices, physical activity, legitimate medication, and blood glucose monitoring by the patients. A positive and encouraging self-care exercise commitment for diabetic patient can be emanated from good social support. Parental support in disease management leads to an effective change in patients' glycaemic control. Nevertheless, the majority of adolescent patients with T2DM are associated to families with sedentary daily routines, high-fat diets, and poor food habits who often have a family history of diabetes. This is likely to be disadvantageous to the management of diabetes in adolescents. The responsibility of clinicians in advancing self-care is imperative and ought to be highlighted. To prevent any long-term complications, it is important to recognize the comprehensive nature of the issue. An orderly, multi-faceted and coordinated progress must be involved to advance self-care practices. CN, LM, YW, and MS designed and directed the study. They were involved in the planning and supervised the study. JE, YK, CN, LM, YW, MH, YH and MS were involved in the interpretation of the data, as well as provided critical intellectual content in the manuscript. JE contributed to writing the manuscript and updated and revised the manuscript to the final version with the assistance of other authors. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. This work was supported in part by Universiti Teknologi MARA UiTM under MyRA Incentive Grant. We also thank KPJUC and CUCMS for partial publication fee support. Bell R. SEARCH for diabetes in youth: a multicenter study of the prevalence, incidence and classification of diabetes mellitus in youth. Control Clin Trials — doi: CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group, Liese AD, D'Agostino RB Jr, Hamman RF, Kilgo PD, Lawrence JM, et al. The burden of diabetes mellitus among US youth: prevalence estimates from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics —8. PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Linder B, Divers J, et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from to JAMA — Chaudhury A, Duvoor C, Reddy Dendi VS, Kraleti S, Chada A, Ravilla R, et al. Clinical review of antidiabetic drugs: implications for type 2 diabetes mellitus management. Front Endocrinol Global Report on Diabetes: Diabetes Programme. Geneva: World Health Organization PubMed Abstract. Nyenwe EA, Jerkins TW, Umpierrez GE, Kitabchi AE. Management of type 2 diabetes: evolving strategies for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism — Miller DK, Austin MM, Colberg SR, Constance A, Dixon DL, MacLeod J, et al. Diabetes Education Curriculum: A Guide to Successful Self-Management. Chicago, IL: American Association of Diabetes Educators. Grey A. Nutritional recommendations for individuals with diabetes. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, Feingold KR, Grossman A, Hershman JM, Koch C, Korbonits M, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Rebar R, Singer F, and Vinik A, editors. South Dartmouth, MA: MDTesxt. com, Inc. Google Scholar. Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, Duker P, Funnell MM, Fischl AH, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes: a joint position statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. ClinDiabetes — Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA —9. Tomky D, Cypress M. American Association of Diabetes Educators AADE Position Statement: AADE 7 Self-Care Behaviors. Chicago, IL: The Diabetes Educators Cooper HC, Booth K, Gill G. Patients' perspectives on diabetes health care education. Health Education Res. Paterson B, Thorne S. Developmental evolution of expertise in diabetes self-management. Clin Nurs Res. Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Role of self-care in management of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord. Johnson SB. Health behavior and health status: concepts, methods, and applications. J Pediatr Psychol. Boulé NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, Wells GA, Sigal RJ. Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 32 Suppl. CrossRef Full Text. Lichner V, Lovaš L. Model of the self-care strategies among slovak helping professionals — qualitative analysis of performed self-care activities. Humanit Soc Sci. Available online at: ssrn. Lin K, Yang X, Yin G, Lin S. Diabetes self-care activities and health-related quality-of-life of individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Shantou, China. J Int Med Res. |