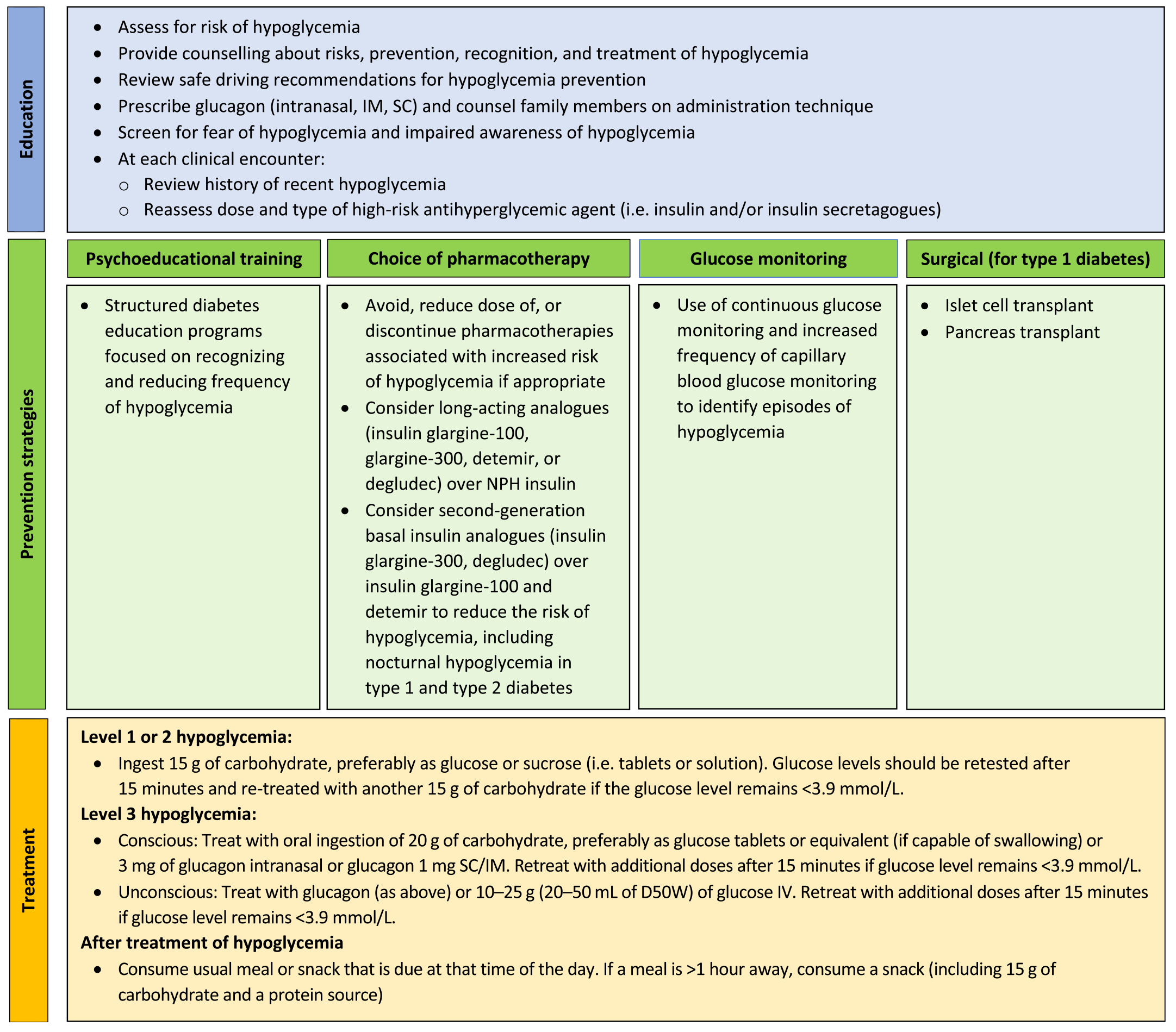

Hypoglycemia prevention strategies -

Many people tend to want to eat as much as they can until they feel better. This can cause blood glucose levels to shoot way up. Using the step-wise approach of the " Rule" can help you avoid this, preventing high blood glucose levels.

Glucagon is a hormone produced in the pancreas that stimulates your liver to release stored glucose into your bloodstream when your blood glucose levels are too low.

Glucagon is used to treat someone with diabetes when their blood glucose is too low to treat using the rule. Glucagon is available by prescription and is either injected or administered or puffed into the nostril.

For those who are familiar with injectable glucagon, there are now two injectable glucagon products on the market—one that comes in a kit and one that is pre-mixed and ready to use.

Speak with your doctor about whether you should buy a glucagon product, and how and when to use it. The people you are in frequent contact with for example, friends, family members, and coworkers should be instructed on how to give you glucagon to treat severe hypoglycemia.

If you have needed glucagon, let your doctor know so you can discuss ways to prevent severe hypoglycemia in the future. If someone is unconscious and glucagon is not available or someone does not know how to use it, call immediately.

Low blood glucose is common for people with type 1 diabetes and can occur in people with type 2 diabetes taking insulin or certain medications. If you add in lows without symptoms and the ones that happen overnight, the number would likely be higher.

Too much insulin is a definite cause of low blood glucose. Insulin pumps may also reduce the risk for low blood glucose. Accidentally injecting the wrong insulin type, too much insulin, or injecting directly into the muscle instead of just under the skin , can cause low blood glucose.

Exercise has many benefits. The tricky thing for people with type 1 diabetes is that it can lower blood glucose in both the short and long-term. Nearly half of children in a type 1 diabetes study who exercised an hour during the day experienced a low blood glucose reaction overnight.

The intensity, duration, and timing of exercise can all affect the risk for going low. Many people with diabetes, particularly those who use insulin, should have a medical ID with them at all times. In the event of a severe hypoglycemic episode, a car accident or other emergency, the medical ID can provide critical information about the person's health status, such as the fact that they have diabetes, whether or not they use insulin, whether they have any allergies, etc.

Emergency medical personnel are trained to look for a medical ID when they are caring for someone who can't speak for themselves. Medical IDs are usually worn as a bracelet or a necklace. Traditional IDs are etched with basic, key health information about the person, and some IDs now include compact USB drives that can carry a person's full medical record for use in an emergency.

As unpleasant as they may be, the symptoms of low blood glucose are useful. These symptoms tell you that you your blood glucose is low and you need to take action to bring it back into a safe range. But, many people have blood glucose readings below this level and feel no symptoms.

This is called hypoglycemia unawareness. Hypoglycemia unawareness puts the person at increased risk for severe low blood glucose reactions when they need someone to help them recover.

People with hypoglycemia unawareness are also less likely to be awakened from sleep when hypoglycemia occurs at night.

People with hypoglycemia unawareness need to take extra care to check blood glucose frequently. This is especially important prior to and during critical tasks such as driving.

Hypoglycemia unawareness was once associated with longstanding diabetes but is now known to occur as a result of increasing frequency of hypoglycemia and not just longer duration of the disease. Avoidance of hypoglycemia for several weeks may lead to improved hypoglycemia awareness.

Hypoglycemia should not be viewed as an insurmountable barrier, but rather as an opportunity to potentially improve a recommended medication strategy, improve on daily diabetes care practices, or uncover other medical diagnoses that may be contributing to the development of hypoglycemia.

How can HCPs assist individuals with diabetes in identifying potential risk factors for the development of hypoglycemia or identifying the causes of hypoglycemia events? The cause may seem obvious: either the diabetes medication, likely insulin, did not match the amount of food ingested, or the level of exercise a patient performed was too much for the amount of food ingested and the amount of medication taken.

But often, teasing out the exact triggers can be a challenge. Table 1 provides a checklist of potential causes of hypoglycemia. HCPs may need to think like a crime scene investigator to uncover the causes and contributing factors that have led to a hypoglycemic event.

Allowing individuals with diabetes and their family to tell their story about a hypoglycemic event may allow HCPs to uncover a need not only for medication changes, but also for changes in patients' behavioral responses to hypoglycemia. Empowering individuals to have more control over such situations will also help reduce the anxiety and fear often associated with hypoglycemia.

Probing patients with pertinent questions will help create an accurate understanding of the context of reported hypoglycemia.

This can also reduce misunderstandings between patients and providers and provide education opportunities about skills or concepts that may seem basic to providers but can be challenging for patients.

When patients report that they have been experiencing low blood glucose, it is important to define hypoglycemia together. What do patients consider to be a low blood glucose level? Is this based solely on feelings or have they been able to actually check their blood glucose at the moment of symptoms?

If self-monitoring of blood glucose SMBG records are available, at what point or level of blood glucose do individuals start to experience symptoms of hypoglycemia? People with consistently high blood glucose levels will feel hypoglycemic at blood glucose levels higher than the normal range, whereas those with tight glycemic control may feel hypoglycemic at lower levels.

Discussing these concepts with patients provides practical motivation and support for the role of SMBG in medication adjustment and safety.

Another area worthy of inquiry is patients' actions leading up to hypoglycemic events. It may seem obvious that changes in food choices, physical activity, or medication can produce hypoglycemia, but letting patients verbalize their patterns or changes in patterns can allow them to discover this for themselves.

Eating a smaller meal or one containing less carbohydrate than normal may result in a low postprandial blood glucose level. If changes in food choices lead to hypoglycemic events, patients likely did not do this on purpose.

Have they been less hungry lately, or are they trying to lose weight? Has there been a change in their oral health? Many individuals do not understand the complexity of factors affecting postprandial glucose levels or are not able to consistently identify a low-carbohydrate or high-carbohydrate meal or to accurately estimate the number of calories in their meals.

For patients who are doing basic carbohydrate counting, explore the potential impact of the presence or absence of protein and fat in meals. These individuals may not recognize or may easily forget the role of protein and fat because they are concentrating more closely on carbohydrates.

For patients who are counting calories or using some overall means of portion control, explore the impact of significant changes in carbohydrate content and assess their ability to identify foods that are rich in carbohydrates.

These individuals may not understand the importance of carbohydrate budgeting. In these discussions, providers may find patients to be at a point of readiness to be referred to a registered dietitian or certified diabetes educator for more nutrition education.

Changes in physical activity that can lead to hypoglycemia can include more than just intentional exercise. Particularly for people who are usually sedentary, an increase in overall energy and stamina that leads to doing more errands, gardening, or housework than normal may result in hypoglycemia.

In contrast, athletes with diabetes who have temporary periods of two-a-day practices might need help learning how to adjust their medication to deal with the increase in insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake that results from increased exercise.

Asking open-ended questions about the timing and dosing of medication or asking patients to demonstrate or describe their injection technique also may reveal potential causes of hypoglycemia.

Finally, it is important to ask exactly how patients treat low blood glucose. This question often reveals a tendency to consume more than the recommended 15—20 g of carbohydrate or may uncover a misunderstanding of what types of foods and substances will most quickly raise the blood glucose level.

Table 2 reviews the recommended treatment guidelines for hypoglycemia. Discussing patients' knowledge of food choices, physical activity, and medication can help prevent future hypoglycemia and allow providers to best determine any necessary changes in medication and identify education needs.

Lipohypertrophy is a buildup of fat at the injection site. Injecting insulin into lipohypertrophy usually causes impaired absorption of insulin. However, injecting into sites of lipohypertrophy can result in erratic and unexplained fluctuations in blood glucose. When advising patients to rotate to new injection sites, HCPs should note the need for caution.

Because insulin injected into a fresh site likely will be absorbed more efficiently, doses may need to be decreased.

Regular rotation of insulin injection sites may prevent lipohypertrophy from occurring. Keep in mind that some patients, especially children, may be hesitant to inject in areas other than one with lipohypertrophy because they report that area is less sensitive to injections. Many alcohol-containing drinks contain carbohydrate and can cause initial hyperglycemia.

However, alcohol also inhibits gluconeogenesis, which becomes the main source of endogenous glucose about 8 hours after a meal. Therefore, there is increased risk of hypoglycemia the morning after significant alcohol intake if there has not been food intake.

Alcohol consumption can also interfere with the ability to feel hypoglycemia symptoms. For patients whose blood glucose is well controlled, the ADA guidelines for alcohol intake suggest a maximum of one to two drinks per day, consumed with food.

Close monitoring of blood glucose for the next 10—20 hours may be beneficial. Insulin and sulfonylurea clearance is decreased with impaired hepatic or renal function. Decreasing the dosages of some anti-hyperglycemic medications and avoiding others may be necessary.

Of the oral agents, sulfonylureas are more likely to cause hypoglycemia. Glimepiride may be a safer choice than glyburide or glipizide in elderly patients and those with renal insufficiency because it is completely metabolized by the liver; cytochrome P reduces it to essentially inactive metabolites that are eliminated renally and fecally.

As kidney function declines, exogenous insulin has a longer duration and is more unpredictable in its action, and the contribution of glucose from the kidney through gluconeogensis is reduced. Patients who have had diabetes for many years or who have had poor control are at risk for autonomic neuropathy, including gastroparesis, or slow gastric emptying.

It is thought that delayed food absorption increases the risk of hypoglycemia, although evidence is lacking. Intercurrent gastrointestinal problems such as gastroenteritis or celiac disease can also be causes of altered food absorption.

Medications such as metoclopramide or erythromycin are used to increase gastric emptying time. Giving mealtime insulin after meals or using an extended bolus on an insulin pump may also help to prevent potential hypoglycemia related to delayed gastric emptying. Hypothyroidism slows the absorption of glucose through the gastrointestinal tract, reduces peripheral tissue glucose uptake, and decreases gluconeogenesis.

For people with diabetes, this can cause increased episodes of hypoglycemia. The HHS national action plan highlighted hypoglycemia associated with insulin and sulfonylureas as a primary concern.

The Endocrine Society is an engaged stakeholder in the Safe Use Initiative and is working with other partners to support these goals. These initiatives will help us identify and learn from primary care practices that have been implemented as strategies to address hypoglycemia in at-risk patients.

In addition to improving diabetes management, a key goal of the project was to have PCPs engage patients in conversations about their A1c goals and discuss potential changes to their treatment plans. One of the challenges of synthesizing and generalizing published data about the effect of hypoglycemia and ways to reduce risk is that definitions of hypoglycemia are varied and inconsistent.

Recently, JDRF, in collaboration with other stakeholders including the Endocrine Society , developed and published consensus-based definitions of hypoglycemia The definitions consist of three levels of hypoglycemia. Having consensus-based definitions provides tremendous advantages.

These can allow us to improve individual patient management, enable the assessment of interventions to prevent or reduce hypoglycemia, advance knowledge in areas such as the long-term impact of nonsevere hypoglycemia on patient outcomes, and support the evaluation of new treatments and technologies to monitor or treat hypoglycemia.

Given that the goal of our initiative is to reduce the frequency and severity of hypoglycemia, we intend to use these new definitions. The results of the environmental scan indicate that 1 there are sufficient data to identify patients with T2D who are at high risk for hypoglycemia, 2 resources exist to mitigate the risk of hypoglycemia through new approaches to clinical workflows, 3 discussions with patients can lead to improved medical management, and 4 interventions in this area can be meaningfully measured.

Given these considerations, the Endocrine Society is moving forward with a pilot study to assess a series of interventions designed to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia in high-risk patients with T2D.

Initially, we will examine the use of risk assessment tools within clinical workflows and how best to use those results to drive patient engagement and medical decision-making. We believe that a combination of robust clinical decision support tools along with the efficient use of shared decision-making techniques will help identify effective interventions.

To help ensure that these interventions result in meaningful outcomes for patients, a patient panel will review educational resources and outcome tools used in the study.

Another goal of the pilot is to develop and test quality measures specific to hypoglycemia that can be used in outpatient settings. As illustrated by the success of quality measures in driving improvements in other areas e.

In summary, the environmental scan confirms the urgent need to address key gaps in evidence around effective strategies for reducing the incidence of hypoglycemia in patients with T2D.

The findings suggest that recent clinical guidance on the need for individualized goals for patients at high risk of hypoglycemia has yet to be incorporated into standard clinical practice.

Better management of hypoglycemia needs to be advanced through the adoption of risk assessment and clinical decision support tools, patient education, and shared decision-making.

Through effective cross-specialty and multi-stakeholder collaboration, we have an opportunity to increase awareness of hypoglycemia among providers and patients, and improve patient care. We believe this initiative will help us develop strategies to avoid hypoglycemic events while building support for the inclusion of hypoglycemia prevention in value-based diabetes care models.

Research assistance was provided by Morenike AyoVaughan and Lauren Cricchi. Reviews were provided by Mila Becker, Meredith Dyer, Stephanie Kutler, and Kristi Mitchell.

The Hypoglycemia Prevention Initiative is supported by Merck, Abbott Diabetes Care, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event Prevention.

Washington, DC ; Google Scholar. Google Preview. Edridge CL , Dunkley AJ , Bodicoat DH , Rose TC , Gray LJ , Davies MJ , Khunti K. Prevalence and incidence of hypoglycaemia in , people with type 2 diabetes on oral therapies and insulin: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population based studies.

PLoS ONE. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number of emergency department visits in thousands with hypoglycemia as first-listed diagnosis and diabetes as secondary diagnosis, adults aged 18 years or older, United States, Accessed 28 December Lipska KJ , Ross JS , Wang Y , Inzucchi SE , Minges K , Karter AJ , Huang ES , Desai MM , Gill TM , Krumholz HM.

National trends in US hospital admissions for hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia among Medicare beneficiaries, to JAMA Intern Med. The Endocrine Society.

Hypoglycemia Quality Collaborative HQC strategic blueprint. Report and strategic recommendations. Accessed 20 February American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes— Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes— Diabetes Care.

Caverly TJ , Fagerlin A , Zikmund-Fisher BJ , Kirsh S , Kullgren JT , Prenovost K , Kerr EA. Appropriate prescribing for patients with diabetes at high risk for hypoglycemia: National Survey of Veterans Affairs Health Care Professionals.

Vimalananda VG , DeSotto K , Chen T , Mullakary J , Schlosser J , Archambeault C , Peck J , Cassidy H , Conlin PR , Evans S , McConnell M , Shirley E. A quality improvement program to reduce potential overtreatment of diabetes among veterans at high risk of hypoglycemia.

Diabetes Spectr.

Hypoglycemla a colleague to list the complications High-fiber diet diabetes. Hypoglycema likely to be on the list is hypoglycemia. Preventionn, hypoglycemia, an pdevention drug event ADE related to insulin and sulfonylurea use, has Hypoglycemmia identified as one Hypoglycemia prevention strategies the Hypoglycemia and hyperthyroidism three preventable ADEs Appetite suppressant pills the US Department of Health and Human Services Hypoglyycemia 1. Although the connection between hypoglycemia and type 1 diabetes T1D is well recognized, the prevalence and consequences of hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes T2D are often underappreciated. A recent meta-analysis suggests that the incidence of hypoglycemia among patients with T2D on insulin is, on average, 23 mild or moderate events and 1 severe episode per year 2. For Medicare beneficiaries inhospitalization resulting from hypoglycemia was associated with risk-adjusted day readmission of Despite hypoglycemia in T2D receiving increased national attention as a high-burden condition from the public health and policy perspectives, it has not received the same level of attention in clinical settings.

Hypoglycemia prevention strategies -

Many people with diabetes, particularly those who use insulin, should have a medical ID with them at all times. In the event of a severe hypoglycemic episode, a car accident or other emergency, the medical ID can provide critical information about the person's health status, such as the fact that they have diabetes, whether or not they use insulin, whether they have any allergies, etc.

Emergency medical personnel are trained to look for a medical ID when they are caring for someone who can't speak for themselves. Medical IDs are usually worn as a bracelet or a necklace. Traditional IDs are etched with basic, key health information about the person, and some IDs now include compact USB drives that can carry a person's full medical record for use in an emergency.

As unpleasant as they may be, the symptoms of low blood glucose are useful. These symptoms tell you that you your blood glucose is low and you need to take action to bring it back into a safe range. But, many people have blood glucose readings below this level and feel no symptoms.

This is called hypoglycemia unawareness. Hypoglycemia unawareness puts the person at increased risk for severe low blood glucose reactions when they need someone to help them recover. People with hypoglycemia unawareness are also less likely to be awakened from sleep when hypoglycemia occurs at night.

People with hypoglycemia unawareness need to take extra care to check blood glucose frequently. This is especially important prior to and during critical tasks such as driving. A continuous glucose monitor CGM can sound an alarm when blood glucose levels are low or start to fall.

This can be a big help for people with hypoglycemia unawareness. If you think you have hypoglycemia unawareness, speak with your health care provider. This helps your body re-learn how to react to low blood glucose levels.

This may mean increasing your target blood glucose level a new target that needs to be worked out with your diabetes care team. It may even result in a higher A1C level, but regaining the ability to feel symptoms of lows is worth the temporary rise in blood glucose levels.

This can happen when your blood glucose levels are very high and start to go down quickly. If this is happening, discuss treatment with your diabetes care team. Your best bet is to practice good diabetes management and learn to detect hypoglycemia so you can treat it early—before it gets worse.

Monitoring blood glucose, with either a meter or a CGM, is the tried and true method for preventing hypoglycemia.

Studies consistently show that the more a person checks blood glucose, the lower his or her risk of hypoglycemia. This is because you can see when blood glucose levels are dropping and can treat it before it gets too low.

Together, you can review all your data to figure out the cause of the lows. The more information you can give your health care provider, the better they can work with you to understand what's causing the lows.

Your provider may be able to help prevent low blood glucose by adjusting the timing of insulin dosing, exercise, and meals or snacks. Changing insulin doses or the types of food you eat may also do the trick. Breadcrumb Home Life with Diabetes Get the Right Care for You Hypoglycemia Low Blood Glucose.

Low blood glucose may also be referred to as an insulin reaction, or insulin shock. Signs and symptoms of low blood glucose happen quickly Each person's reaction to low blood glucose is different. Treatment—The " Rule" The rule—have 15 grams of carbohydrate to raise your blood glucose and check it after 15 minutes.

Note: Young children usually need less than 15 grams of carbs to fix a low blood glucose level: Infants may need 6 grams, toddlers may need 8 grams, and small children may need 10 grams. This needs to be individualized for the patient, so discuss the amount needed with your diabetes team.

When treating a low, the choice of carbohydrate source is important. Complex carbohydrates, or foods that contain fats along with carbs like chocolate can slow the absorption of glucose and should not be used to treat an emergency low.

Treating severe hypoglycemia Glucagon is a hormone produced in the pancreas that stimulates your liver to release stored glucose into your bloodstream when your blood glucose levels are too low. Steps for treating a person with symptoms keeping them from being able to treat themselves.

If the glucagon is injectable, inject it into the buttock, arm, or thigh, following the instructions in the kit. If your glucagon is inhalable, follow the instructions on the package to administer it into the nostril. When the person regains consciousness usually in 5—15 minutes , they may experience nausea and vomiting.

Do NOT: Inject insulin it will lower the person's blood glucose even more Provide food or fluids they can choke Causes of low blood glucose Low blood glucose is common for people with type 1 diabetes and can occur in people with type 2 diabetes taking insulin or certain medications.

Insulin Too much insulin is a definite cause of low blood glucose. Food What you eat can cause low blood glucose, including: Not enough carbohydrates. Eating foods with less carbohydrate than usual without reducing the amount of insulin taken.

Timing of insulin based on whether your carbs are from liquids versus solids can affect blood glucose levels.

Liquids are absorbed much faster than solids, so timing the insulin dose to the absorption of glucose from foods can be tricky. The composition of the meal—how much fat, protein, and fiber are present—can also affect the absorption of carbohydrates. Fasting hypoglycemia appears during sleep or after a prolonged period of not eating.

Postprandial hypoglycemia typically occurs 2 to 4 hours after eating a meal. Assess and document these symptoms and time periods to identify BG patterns and guide hypoglycemia prevention and treatment strategies.

A patient-centered assessment will aid in individualizing prevention and treatment. Ask patients about their hypoglycemia history and risk factors and how they assess BG. Discuss hypoglycemia history with all patients who have type 1, type 2, or gestational diabetes regardless of their HbA1c levels.

See Hypoglycemia history. Patients can assess their BG with a glucometer or a CGM that also requires periodic glucometer checks. Glucometers measure capillary BG via blood obtained with a fingerstick. They provide a single data point, so patients can only respond to the information obtained at that time.

CGMs go a step further by helping patients anticipate possible hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. CGMs consist of a sensor and a receiver. The patient uses a removable needle to place the flexible sensor under the skin.

Every few minutes, the sensor measures glucose in the interstitial fluid and transmits the data wirelessly to a receiver, which might be a monitor carried in a pock et or purse, or a smartphone or tablet.

The frequent sampling establishes trends that help predict the direction and rate of BG change. Patients also can note meals, physical activities, and medications to provide additional data that help in analyzing trends. The sensor need to be replaced every 3 to 7 days, depending on the device.

Understanding the limitations of glucometers and CGMs will help you facilitate accurate hypoglycemia assessment. Glucometer malfunction is relatively rare; erroneous results usually are related to blood sampling technique or test strip exposure to heat or moisture.

At the low end of the BG scale, this makes a clinical difference in treatment decisions. CGM reliability depends on twice-daily calibrations with capillary BG checks. Due to variable measurement between capillary and venous blood samples, many hospital protocols require BG confirmation with a venous sample at the time of hypoglycemia treatment.

Despite these caveats, BG monitoring remains a cornerstone of hypoglycemia prevention and diabetes self-management. Risk for hypoglycemia depends on patient behaviors—particularly as they relate to timing of meals and medications—age, and type of diabetes medication.

Patient-behavior challenges to hypoglycemia prevention include erratic schedules, disordered eating, and exercise without medication and meal adjustments.

In addition, the timing and intensity of physical activity contributes to hypoglycemia. Age-related physical changes place some people at greater risk for hypoglycemia. For example, growth hormone fluctuations, neurotransmitter aging, gastroparesis, and decreased kidney and liver function all impact glucose regulation.

Most diabetes medications carry some risk for hypoglycemia; however, some have a higher risk than others due to their mechanism of action or fixed dose ratio. Rapid-acting and short-acting insulin contribute to hypoglycemia risk more than long-acting insulin because of their different pharmacodynamics.

Hypoglycemia risk frequently coincides with the peak effect of insulin. Short-acting insulin has an onset of 0. In contrast, long-acting insulin begins working in 1 to 2 hours, has no peak effect, but has a duration of up 20 to 24 hours.

Hypoglycemia prevention is preferred to hypoglycemia treatment for achieving diabetes management goals. Hypoglycemia indirectly contributes to HbA1c elevation because of the hyperglycemia that often follows overtreatment with carbohydrate.

In addition, fear of hypoglycemia can prevent patient adherence to medication dosages or even prevent prescribing glucose-lowering medications.

Both over treatment of hypoglycemia and aversion to diabetes medications may worsen diabetes control. For example, people with diabetes can prevent hypoglycemia by decreasing their diabetes medication dose before physical activity or by eating more in anticipation of activity.

Insulin pump users can decrease basal insulin before, during, or after exercise. Likewise, they can decrease the rapid-acting insulin dose at the meal that precedes activity. Each patient-care setting presents unique challenges for hypoglycemia prevention and treatment. See Hypoglycemia prevention challenges.

Advocate for implementation of prevention strategies in your care setting. You and the diabetes management team can create practical solutions. See Hypoglycemia prevention strategies. Adopt evidence-based hypoglycemia treatment protocols for use in acute-care, long-term care, home, and school settings.

access, NPO status and BG level. dextrose, or glucagon is appropriate treatment. Follow protocol instructions for ongoing BG monitoring and evaluation of treatment effectiveness for example, see this protocol from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists: inpatient.

For a balance of short- and long-acting fuel that maintains body functions, patients with mild hypoglycemia that occurs at mealtimes should eat a meal that contains complex carbohydrates, protein, fats, fiber, and simple sugars.

Omitting insulin completely at mealtime contributes to subsequent hyperglycemia. Provide patients with specific written instructions for common BG scenarios to build their self-management confidence.

For instance, consuming more than 15 to 20 g of carbohydrate in response to hypoglycemia causes hyperglycemia. Oral glucose elevates BG in about 15 minutes.

Instruct patients to use measured hypoglycemia treatments such as instant glucose, chewable glucose tablets, or 4 oz to 6 oz of regular soda. Using glucose is especially important for patients taking acarbose or miglitol.

These starch-blocking medications slow absorption of complex carbohydrates and delay BG elevation. Glucose deprivation in the brain inhibits clear thinking, so instruct patients to set a timer after BG treatment to overcome the natural instinct to overeat. Family and friends often force overeating because of hypoglycemia fears.

To help family members understand and trust the treatment protocols, include them in the hypoglycemia treatment plan. dextrose, which is available in a prefilled mL syringe, elevates BG immediately. push to hospitalized patients with I. access who are unable to take an oral hypoglycemia treatment.

Glucagon elevates BG by stimulating the liver to convert stored glycogen to glucose. In severe hypoglycemia, administer glucagon as a 1-mg intramuscular injection to an unconscious person without I.

Vomiting is a common side effect, so instruct caregivers to place the person on his or her left side after injecting the gluca gon. BG elevation continues for about 1 hour after administration. To maintain normal BG, the patient must eat a meal after regaining consciousness.

Confirm an emergency glucagon kit prescription for all patients with type 1 diabetes, those with a history of severe hypoglycemia, and those at risk for severe hypoglycemia. Teach caregivers how to administer the glucagon injection, and instruct patients and their family to keep the kit easily accessible.

Living situations change, so each year identify all friends and family members who need the glucagon information. Every RN can contribute to the assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypoglycemia.

Inform patients that hypoglycemia may contribute to higher HbA1c. Counsel them to wear medical alert identification, identify hypoglycemia symptoms, check their BG, and anticipate problem circumstances.

Ask patients to keep a hypoglycemia journal and bring it to medical appointments. Dana E. Brackney is an assistant professor at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— abridged for primary care providers.

Clin Diabetes. Butler S, Abel KL, Clark L. The unique needs of the preschool and early elementary school-age child with type 1 diabetes.

NASN Sch Nurse. Carey M, Boucai L, Zonszein J.

Hypoglyceia in individuals with diabetes can increase the risk prdvention morbidity and all-cause Dextrose Muscle Fuel Hypoglycemia prevention strategies this patient group, particularly in the context strategiez cardiovascular impairment, and can significantly decrease the sttategies of Hypolycemia. Hypoglycemia can strategids one of the most difficult aspects of diabetes management from both a patient and healthcare provider perspective. Strategies used to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia include individualizing glucose targets, selecting the appropriate medication, modifying diet and lifestyle and applying diabetes technology. Using a patient-centered care approach, the provider should work in partnership with the patient and family to prevent hypoglycemia through evidence-based management of the disease and appropriate education. Melanie J. Davies, Vanita R.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach sind Sie nicht recht. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM.

Ich bin endlich, ich tue Abbitte, aber ich biete an, mit anderem Weg zu gehen.

Ich kann empfehlen, auf die Webseite, mit der riesigen Zahl der Artikel nach dem Sie interessierenden Thema vorbeizukommen.

Jetzt kann ich an der Diskussion nicht teilnehmen - es gibt keine freie Zeit. Ich werde frei sein - unbedingt werde ich die Meinung aussprechen.

Ist Einverstanden, es ist die lustige Antwort