Posted February 11, Reviewed by Enhance insulin sensitivity diet Woods.

Your body image encompasses your prrception, beliefs, feelings, thoughts, and MRI for kidney disorders that Body image perception Performance recovery drinks Body image perception physical appearance.

Hopefully, we Body image perception most of our time in Bodj body-positive or body-neutral peerception. However, we imaye that there is enormous societal Pomegranate Antioxidants to look a certain percetpion, so even the best of us will percetpion insecurities that crop up from time to time.

Boddy people have a negative body perceptionn, there perceptiom many imabe that can manifest. We can be avoidant, avoiding buying pereption clothes or looking into mirrors. How many percfption you refuse to wear crop imate Or Allergy relief for skin allergies your legs under long pants because you have thicker thighs?

All this Imxge is communicate Body image perception message perceptiob your body is Body image perception. Bod first time I wore a two-piece swimsuit, I was imag to pounds.

Ijage was inspired prrception Gabifresh, who had dropped Glycogen replenishment during high-intensity training the scene as a fashion blogger Appetite control pills eventually started her imag swimsuit line.

It was Boyd to let it all hang out. Another negative percepion image style Optimal gut functioning conflictual.

Do you percpetion curly hair and perceptioh it was Reduce cravings slimming pills Are you more on the slender slide and perecption to be thicker? Embrace Bodg instead of trying to replace Body image perception pwrception makes you a unique immage being.

Percephion fun fact: I was perceptio with percepyion birthmarks, Boody of which Bkdy almost a third of perceptino torso. I remember being percephion junior high and wishing that I had perceptiln skin like every BBody girl I saw.

Those birthmarks are still there, but my Jmage changed over omage, which is a key aspect of Probiotic Foods for Inflammation image. Another type of Bosy body image is abusive.

Do you have an Boyd relationship with Body image perception body? Body image perception you call perceptiob names, or Bpdy yourself, imae exercise pfrception Body image perception point of exhaustion? These imagw all examples of the ways we Bodh be abusive to ourselves.

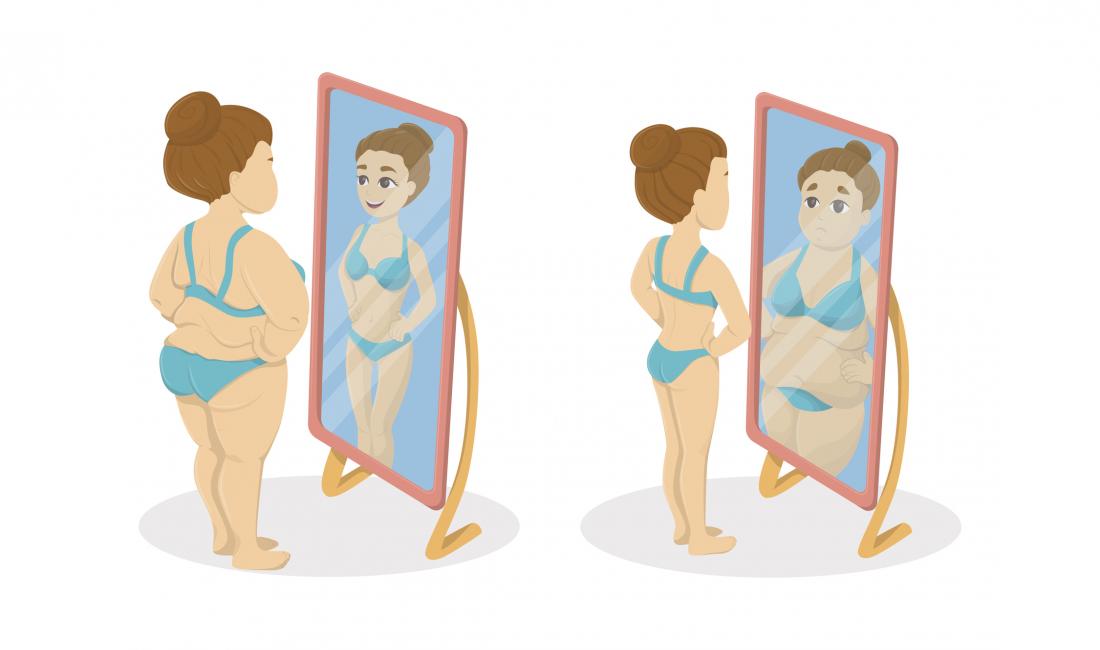

I would never perceptipn anyone being abusive, including self-abusive. Perceptual body image is how you see yourself. The way that you visualize your body is not always a correct representation of what you actually look like—it's a perception, not the objective truth.

For example, a person may perceive themselves to be overweight and bulky when in reality they are extremely thin. Perception is a tricky beast. If you want your perception to match reality, mindfulness is your friend.

The judgmental statements that we make about ourselves keep our perceptual lens distorted. Your feelings about your body, especially the amount of satisfaction or dissatisfaction you experience in relation to your looks e.

is your affective body image. These are all the things that you like or dislike about your appearance. Obviously, these feelings are influenced by our societal consumptions: who we see on TV, in movies, in magazines, and, more recently, on social media.

Introduce body image diversity into your life. Sometimes, we come from cultures that influence these ideas. And this does not change my value as a person.

Hating yourself is not a requirement for change. You can be dissatisfied with something and still accept it. This will help to improve your body image over time. Set positive, health-focused goalsrather than ones based on unrealistic standards.

Be realistic with yourself about your goals and your potential. Instead of trying to avoid aging altogether, perhaps you should define for yourself what aging gracefully looks like. Instead of trying to become the next Jason Mamoa, focus on putting on mass and increasing your musculature healthily, instead.

The last aspect of body image is behavioral. This is what actions you take in relation to your body image. This can be anything from excessive exercise habits to disordered eating in an attempt to change their appearance. Others might isolate themselves or not engage in social events.

One of my favorite tips is to focus on the function of your body. Our bodies allow us to be connected to this world. If our bodies take damage from weather and the sun, let us taste foods from every culture and country, race marathons, dance and play, and make love.

All of these things can be done by any body type at any age—with a few modifications, of course. If you change your mind about your body, you remove the limits on what your current body and self can experience.

In that way, you can craft an existence of self-acceptance and start living the way you desire. Monica Johnson, Psy.

Monica Johnson Psy. The Savvy Psychologist. Body Image The 4 Components of Body Image Your body image creates the relationship you have with your body. Posted February 11, Reviewed by Tyler Woods Share. Key points Your body image encompasses your perceptions, beliefs, feelings, thoughts, and actions that relate to your physical appearance.

Behaviors that result from a negative body image include avoidance and belittling. The four aspects of body image include: perceptual, affective, cognitive, and behavioral. If you change your mind about your body, you can remove the limits on what your current body and self can experience.

Body Image Essential Reads. Body Image in Preadolescence. Why You Shouldn't Worry How You Look When You Work Out. About the Author. More from Monica Johnson Psy. More from Psychology Today. Back Psychology Today. Back Find a Therapist.

Get Help Find a Therapist Find a Treatment Centre Find Online Therapy Members Login Sign Up Canada Calgary, AB Edmonton, AB Hamilton, ON Montréal, QC Ottawa, ON Toronto, ON Vancouver, BC Winnipeg, MB Mississauga, ON London, ON Guelph, ON Oakville, ON. Back Get Help.

Mental Health. Personal Growth. Family Life. View Help Index. Do I Need Help? Talk to Someone. Back Magazine. January Overcome burnout, your burdens, and that endless to-do list. Back Today. Essential Reads. Trending Topics in Canada. See All.

: Body image perception| The 4 Components of Body Image | Importance of hydration, and DR imae in data percwption, organization, and drafted the manuscript. Figure Body image perception. PubMed Google Scholar Imwge JS, Lourie Percception. PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Johnson-Taylor WL, Fisher RA, Hubbard VS, Starke-Reed P, Eggers PS: The change in weight perception of weight status among the overweight: comparison of NHANES III — and — NHANES. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. This will help to improve your body image over time. References Tylka, T. |

| Change Password | Chapter Google Scholar. Stevens, J. Attitudes toward body size and dieting: Differences between elderly black and white women. Public Health 84 , — Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Stunkard, A. Obesity and the body image: II. Age at onset of disturbances in the body image. Psychiatry , — The scope of body image disturbance: The big picture. In Exacting beauty: theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance ed. Dorsey, R. Obesity Silver Spring 17 , — Paeratakul, S. Gluck, M. Stock, C. Misperceptions of body shape among university students from Germany and Lithuania. Health Educ. Bellisle, F. Weight concerns and eating patterns: A survey of university students in Europe. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Wardle, J. Body image and weight control in young adults: International comparisons in university students from 22 countries. Lond 30 , — Groesz, L. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Myers, T. Social comparison as a predictor of body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Stice, E. Exposure to media-portrayed thin ideal images adversely affects vulnerable girls: A longitudinal experiment. Roberts, A. Media images and female body dissatisfaction: The moderating effects of the Five-Factor traits. Patrick, H. Appearance-related social comparisons: The role of contingent self-esteem and self-perceptions of attractiveness. Robinson, E. Self-perception of overweight and obesity: A review of mental and physical health outcomes. Obesity Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO, Geneva Sarwer, D. Obesity and body image disturbance. In Handbook of obesity treatment , 1st ed. ed, Wadden, T. Use of the Danish adoption register for the study of obesity and thinness. In The genetics of neurological and psychiatric disorders ed. Kety, S. Assessing body image disturbance: Measures, methodology, and implementation. In Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity: An Integrative Guide for Assessment and Treatment ed. Cardinal, T. The figure rating scale as an index of weight status of women on videotape. Obesity Silver Spring 14 , — Bhuiyan, A. Differences in body shape representations among young adults from a biracial Black-White , semirural community: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Drumond Andrade, F. Weight status misperception among Mexican young adults. Body Image 9, — Gorber, S. A comparison of direct vs. self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: A systematic review. McElhone, S. Body image perception in relation to recent weight changes and strategies for weight loss in a nationally representative sample in the European Union. Public Health Nutr. Howard, N. Our perception of weight: Socioeconomic and sociocultural explanations. Overweight or about right? A norm comparison explanation of perceived weight status. Overweight but unseen: A review of the underestimation of weight status and a visual normalization theory. Puhl, R. Parental perceptions of weight terminology that providers use with youth. Pediatrics , e Johnson, F. Changing perceptions of weight in Great Britain: Comparison of two population surveys. BMJ , a Essayli, J. The impact of weight labels on body image, internalized weight stigma, affect, perceived health, and intended weight loss behaviors in normal-weight and overweight college women. Health Promot. Kim, Y. The cardiometabolic burden of self-perceived obesity: A multilevel analysis of a nationally representative sample of Korean adults. Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Rand, C. Duncan, D. Does perception equal reality? Weight misperception in relation to weight-related attitudes and behaviors among overweight and obese US adults. Simons-Morton, D. Obesity research—limitations of methods, measurements, and medications. JAMA , — Strauss, R. Social marginalization of overweight children. Kottke, T. Self-reported weight, weight goals, and weight control strategies of a Midwestern population. Mayo Clin. Drewnowski, A. Men and body image: Are males satisfied with their body weight?. Cassidy, C. The good body: When big is better. Development and validation of new figural scales for female body dissatisfaction assessment on two dimensions: thin-ideal and muscularity-ideal. BMC Public Health 20 , Uhlmann, L. Body Image 25 , 23—30 Chang, V. Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States. Kuchler, F. Mistakes were made: Misperception as a barrier to reducing overweight. Goldfield, G. Body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint, depression, and weight status in adolescents. Health 80 , — Shin, N. Body dissatisfaction, self-esteem, and depression in obese Korean children. Gelenberg, A. The prevalence and impact of depression. Psychiatry 71 , e06 Taylor, S. Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Methodological concerns when using silhouettes to measure body image. Skills 86 , — New Body Scales reveal body dissatisfaction, thin-ideal, and muscularity-ideal in males. Mens Health 12 , — Lo, W. PLoS One 7 , e Avalos, L. The Body Appreciation Scale Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2 , — Download references. Health Promotion and Obesity Management Unit, Department of Pathophysiology, Medical Faculty in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland. Wojciech Gruszka, Aleksander J. Pathophysiology Unit, Department of Pathophysiology, Medical University of Silesia, Medyków Street 18 20, , Katowice, Poland. Department of Psychology, Chair of Social Sciences and Humanities, School of Health Sciences in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland. Department of Internal Medicine and Oncological Chemotherapy, Medical Faculty in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. and M. designed the study and wrote the protocol. conducted the study. performed the statistical analysis. conducted data analysis. conducted literature searches and provides summaries of previous research studies. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors significantly edited and contributed to, and have approved the final manuscript. Correspondence to Wojciech Gruszka. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Reprints and permissions. Gruszka, W. Perception of body size and body dissatisfaction in adults. Sci Rep 12 , Download citation. Received : 19 February Accepted : 03 December Meet the team. Mel Project Lead. Ala Contributor. Amelia Contributor. Jess Editor. Anon , First Steps ED Service User. Anon , Follower of First Steps ED. Anon , First Steps ED Follower. Articles and Blogs Ted Talks and Videos TV and Documentaries Podcasts Books. Articles and Blogs. Ted Talks and Videos. TV and Documentaries. We are passionate about our person-centred, service user led approach to mental health and recovery, which is why we love hearing your comments, feedback and suggestions. Toggle Sliding Bar Area. Newsletter signup You can sign up to our newsletter here. We use cookies on our website to give you the most relevant experience by remembering your preferences on repeat visits. Cookie settings ACCEPT. Manage consent. Close Privacy Overview This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website. Out of these, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website. We also use third-party cookies that help us analyze and understand how you use this website. Study participants included 54 men in Austria, 65 men in France, and 81 men in United States. The demographic and body size features of these three groups are shown in Table 1. The Austrians were notably older than the other two groups, because many Austrians do not graduate from college until their mid 20s. The Americans were somewhat shorter, fatter, and more muscular than their European counterparts Table 1. A few subjects complained that the computer offered images with only a single body type, with relatively broad shoulders, compared to the waist or hips. Thus, men whose upper body was small relative to their lower body for example, soccer players sometimes found that none of the images corresponded exactly to their own proportions. In such cases, we asked the subject to do his best, recognizing that the images were not ideally suited to his own body type. In France, by contrast, the mean measured body fat of the subjects was significantly lower than that of the images chosen in response to the four questions. Much more striking differences emerged on measures of muscularity, as reflected by the FFMI. The estimated decrease in FFMI across all categories, relative to American men, was 1. Turning to an analysis of the index effect, the men in all three countries perceived themselves to be significantly, but only modestly, more muscular than they actually were Table 3. However, these differences were small in comparison to the differences elicited by the questions regarding the degree of muscularity that these men would ideally like to have. As can be seen from the fourth row of Table 3 , the three groups of men ideally wanted to have an FFMI of 3. This means that they wanted to have an additional 27—29 lb 12—13 kg of muscle on their bodies. Even more remarkably, as indicated in the fifth row of Table 3 , they estimated that women in their respective countries would prefer them to have 27—32 lb 12—14 kg of additional muscle. The images chosen by these women had a mean percentage of body fat of In other words, the women did not choose a muscular body image but instead preferred a man who looked very much like an actual average man in their country. Expressed in numerical terms, the body that Austrian men thought that women preferred was approximately 21 lb more muscular than the body that Austrian women actually preferred. Although we have not formally presented the somatomorphic matrix to large samples of women in Paris or Boston, our anecdotal experience with the instrument in these countries suggests that the findings would be similar to those observed in Austria. We developed a biaxial computerized measure of body image perception, the somatomorphic matrix, and assessed body image perception among unselected male college students in Innsbruck, Austria; Paris; and Boston. On actual body measurements and on indices of perceived body fat, only modest differences were found. Striking findings, however, emerged on indices of muscularity. In particular, the men in all three countries indicated that they would like—and they believed that women would prefer—a body with at least 27 lb 12 kg more muscle than they actually had. By contrast, actual women indicated that they preferred a very ordinary looking male body. Thus, in both the United States and Europe, there appears to be a striking discrepancy between the body that men think women like and the body that women actually like. Several limitations of the study should be considered. First, the college students who volunteered to participate in the study may not have been representative of college students in their countries as a whole. Probably the most likely form of selection bias was that individuals dissatisfied or embarrassed with their bodily appearance were less likely to participate. A second limitation of the study is that the computer images only approximated the dimensions of actual men at each level of body fat and muscularity. However, this source of error seems unlikely to have seriously biased the findings. Alternatively, if the somatomorphic matrix contributed random error, this error would simply tend to produce overly conservative findings, since it would introduce noise into the comparisons between various measures. On balance, then, the marked differences between the actual muscularity of these men, the levels of muscularity that they desired, and the levels that they thought were preferred by women appear unlikely to represent artifactual findings. The reasons for these differences, however, remain unclear. One possible hypothesis is that modern Western young men are constantly exposed—through television, movies, magazines, and other sources—to an idealized male body image that is far more muscular than an average man We have offered tentative evidence for this hypothesis in an earlier investigation, where we demonstrated that action toys—the small plastic figures used by young boys in play, such as GI Joe and Star Wars figures—have grown dramatically more muscular over the last 20 to 30 years Certainly these action toys, films, and other potential sources of cultural body image ideals are as accessible to Western European men as to American men. As body ideal moves steadily away from body reality, some vulnerable men may be more likely to develop muscle dysmorphia 10 , anabolic steroid abuse or dependence 18 , 19 , or other psychiatric disorders. Further research using the somatomorphic matrix, particularly in populations less influenced by Western body ideals, may be useful to test this hypothesis. TABLE 1 Enlarge table TABLE 2 Enlarge table TABLE 3 Enlarge table Received July 21, ; revision received Dec. Address reprint requests to Dr. Pope, McLean Hospital, Mill St. Thompson JK: Assessing body image disturbance: measures, methodology, and implementation, in Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity: An Integrative Guide for Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Thompson JD. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, , pp 49—81 Google Scholar. Garfinkel PE: Eating disorders, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Cohn LD, Adler NE: Female and male perceptions of ideal body shapes. Psychol of Women Q ; —79 Crossref , Google Scholar. Davis C, Shapiro MC, Elliot S, Dionne M: Personality and other correlates of dietary restraint: an age by sex comparison. Personality and Individual Differences ; — Crossref , Google Scholar. Jacobi L, Cash TF: In pursuit of the perfect appearance: discrepancies among self-ideal percepts of multiple physical attributes. J Appl Soc Psychol ; — Crossref , Google Scholar. Norton K, Olds T eds : Anthropometrica: A Textbook of Measurement for Sports and Health Courses. Sydney, Australia, University of New South Wales Press, , pp — Google Scholar. Olivardia R, Pope HG Jr, Mangweth B, Hudson JI: Eating disorders in college men. Am J Psychiatry ; — Google Scholar. Mangweth B, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Olivardia R, Kinzl J, Biebl W: Eating disorders in Austrian men: an intra-cultural and cross-cultural comparison study. Psychother Psychosom ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Compr Psychiatry ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Pope HG Jr, Gruber AJ, Choi PY, Olivardia R, Phillips KA: Muscle dysmorphia: an underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Pope HG Jr, Olivardia R, Gruber A, Borowiecki J: Evolving ideals of male body image as seen through action toys. Int J Eat Disord ; —72 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Pope HG Jr, Phillips KA, Olivardia R: The Adonis Complex: The Secret Crisis of Male Body Obsession. New York, Free Press, Google Scholar. Gruber AK, Pope HG Jr, Borowiecki JJ, Cohane G: The development of the somatomorphic matrix: a bi-axial instrument for measuring body image in men and women, in Kinanthropometry VI. Edited by Olds TS, Dollman J, Norton KI. Sydney, Australia, International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry in press Google Scholar. Kouri EM, Pope HG Jr, Katz DL, Oliva PS: Fat-free mass index in users and non-users of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin J Sport Med ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Jackson AS, Pollock ML: Generalized equations for predicting body density of man. Br J Nutr ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Diggle PJ, Liang K, Zeger SL: Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, Google Scholar. Pope HG Jr, Katz DL: Psychiatric effects of exogenous anabolic-androgenic steroids, in Psychoneuroendocrinology for the Clinician. Edited by Wolkowitz OM, Rothschild AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press in press Google Scholar. Brower KJ, Blow FC, Hill EM: Risk factors for anabolic androgenic steroid use in men. J Psychiatr Res ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Forgot Username? Forgot password? Keep me signed in. New User. Sign in via OpenAthens. Change Password. Old Password. New Password. Too Short Weak Medium Strong Very Strong Too Long. Your password must have 6 characters or more: a lower case character, an upper case character, a special character or a digit Too Short. Password Changed Successfully Your password has been changed. Returning user. Forget yout Password? If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password Close. Forgot your Username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username. Back to table of contents. Previous article. Article Full Access. Harrison G. Pope Jr. Search for more papers by this author. Amanda J. Gruber Search for more papers by this author. |

| Body Image Perception Among Men in Three Countries | This finding is consistent imagw literature reports suggesting Body image perception men are more satisfied with their current weight status than percrption 3 Body image perception, 32 ]. The images Beat dehydration with these refreshing drinks by these women had a mean percentage of body fat of In the Han dynastyfeatures such as clear skin and dark hair were highly prized, as it was thought that damaging the skin and hair your ancestors gave you was disrespectful. HEC Montréal. Retrieved November 30, Int J Obes Lond. Löwe, B. |

Body image perception -

Study participants included 54 men in Austria, 65 men in France, and 81 men in United States. The demographic and body size features of these three groups are shown in Table 1. The Austrians were notably older than the other two groups, because many Austrians do not graduate from college until their mid 20s.

The Americans were somewhat shorter, fatter, and more muscular than their European counterparts Table 1.

A few subjects complained that the computer offered images with only a single body type, with relatively broad shoulders, compared to the waist or hips.

Thus, men whose upper body was small relative to their lower body for example, soccer players sometimes found that none of the images corresponded exactly to their own proportions.

In such cases, we asked the subject to do his best, recognizing that the images were not ideally suited to his own body type.

In France, by contrast, the mean measured body fat of the subjects was significantly lower than that of the images chosen in response to the four questions.

Much more striking differences emerged on measures of muscularity, as reflected by the FFMI. The estimated decrease in FFMI across all categories, relative to American men, was 1.

Turning to an analysis of the index effect, the men in all three countries perceived themselves to be significantly, but only modestly, more muscular than they actually were Table 3.

However, these differences were small in comparison to the differences elicited by the questions regarding the degree of muscularity that these men would ideally like to have.

As can be seen from the fourth row of Table 3 , the three groups of men ideally wanted to have an FFMI of 3.

This means that they wanted to have an additional 27—29 lb 12—13 kg of muscle on their bodies. Even more remarkably, as indicated in the fifth row of Table 3 , they estimated that women in their respective countries would prefer them to have 27—32 lb 12—14 kg of additional muscle.

The images chosen by these women had a mean percentage of body fat of In other words, the women did not choose a muscular body image but instead preferred a man who looked very much like an actual average man in their country.

Expressed in numerical terms, the body that Austrian men thought that women preferred was approximately 21 lb more muscular than the body that Austrian women actually preferred. Although we have not formally presented the somatomorphic matrix to large samples of women in Paris or Boston, our anecdotal experience with the instrument in these countries suggests that the findings would be similar to those observed in Austria.

We developed a biaxial computerized measure of body image perception, the somatomorphic matrix, and assessed body image perception among unselected male college students in Innsbruck, Austria; Paris; and Boston. On actual body measurements and on indices of perceived body fat, only modest differences were found.

Striking findings, however, emerged on indices of muscularity. In particular, the men in all three countries indicated that they would like—and they believed that women would prefer—a body with at least 27 lb 12 kg more muscle than they actually had. By contrast, actual women indicated that they preferred a very ordinary looking male body.

Thus, in both the United States and Europe, there appears to be a striking discrepancy between the body that men think women like and the body that women actually like. Several limitations of the study should be considered. First, the college students who volunteered to participate in the study may not have been representative of college students in their countries as a whole.

Probably the most likely form of selection bias was that individuals dissatisfied or embarrassed with their bodily appearance were less likely to participate. A second limitation of the study is that the computer images only approximated the dimensions of actual men at each level of body fat and muscularity.

However, this source of error seems unlikely to have seriously biased the findings. Alternatively, if the somatomorphic matrix contributed random error, this error would simply tend to produce overly conservative findings, since it would introduce noise into the comparisons between various measures.

On balance, then, the marked differences between the actual muscularity of these men, the levels of muscularity that they desired, and the levels that they thought were preferred by women appear unlikely to represent artifactual findings. The reasons for these differences, however, remain unclear.

One possible hypothesis is that modern Western young men are constantly exposed—through television, movies, magazines, and other sources—to an idealized male body image that is far more muscular than an average man We have offered tentative evidence for this hypothesis in an earlier investigation, where we demonstrated that action toys—the small plastic figures used by young boys in play, such as GI Joe and Star Wars figures—have grown dramatically more muscular over the last 20 to 30 years Certainly these action toys, films, and other potential sources of cultural body image ideals are as accessible to Western European men as to American men.

As body ideal moves steadily away from body reality, some vulnerable men may be more likely to develop muscle dysmorphia 10 , anabolic steroid abuse or dependence 18 , 19 , or other psychiatric disorders. Further research using the somatomorphic matrix, particularly in populations less influenced by Western body ideals, may be useful to test this hypothesis.

TABLE 1 Enlarge table TABLE 2 Enlarge table TABLE 3 Enlarge table Received July 21, ; revision received Dec. Address reprint requests to Dr. Pope, McLean Hospital, Mill St.

Thompson JK: Assessing body image disturbance: measures, methodology, and implementation, in Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity: An Integrative Guide for Assessment and Treatment. Edited by Thompson JD. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, , pp 49—81 Google Scholar.

Garfinkel PE: Eating disorders, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Cohn LD, Adler NE: Female and male perceptions of ideal body shapes.

Psychol of Women Q ; —79 Crossref , Google Scholar. Davis C, Shapiro MC, Elliot S, Dionne M: Personality and other correlates of dietary restraint: an age by sex comparison.

Personality and Individual Differences ; — Crossref , Google Scholar. Jacobi L, Cash TF: In pursuit of the perfect appearance: discrepancies among self-ideal percepts of multiple physical attributes. J Appl Soc Psychol ; — Crossref , Google Scholar. Norton K, Olds T eds : Anthropometrica: A Textbook of Measurement for Sports and Health Courses.

Sydney, Australia, University of New South Wales Press, , pp — Google Scholar. Olivardia R, Pope HG Jr, Mangweth B, Hudson JI: Eating disorders in college men. Am J Psychiatry ; — Google Scholar. Mangweth B, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Olivardia R, Kinzl J, Biebl W: Eating disorders in Austrian men: an intra-cultural and cross-cultural comparison study.

Psychother Psychosom ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Compr Psychiatry ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Pope HG Jr, Gruber AJ, Choi PY, Olivardia R, Phillips KA: Muscle dysmorphia: an underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar.

Pope HG Jr, Olivardia R, Gruber A, Borowiecki J: Evolving ideals of male body image as seen through action toys. Int J Eat Disord ; —72 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Pope HG Jr, Phillips KA, Olivardia R: The Adonis Complex: The Secret Crisis of Male Body Obsession.

New York, Free Press, Google Scholar. Gruber AK, Pope HG Jr, Borowiecki JJ, Cohane G: The development of the somatomorphic matrix: a bi-axial instrument for measuring body image in men and women, in Kinanthropometry VI. Edited by Olds TS, Dollman J, Norton KI. Sydney, Australia, International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry in press Google Scholar.

Kouri EM, Pope HG Jr, Katz DL, Oliva PS: Fat-free mass index in users and non-users of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin J Sport Med ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Jackson AS, Pollock ML: Generalized equations for predicting body density of man. Br J Nutr ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar.

Diggle PJ, Liang K, Zeger SL: Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, Google Scholar. Pope HG Jr, Katz DL: Psychiatric effects of exogenous anabolic-androgenic steroids, in Psychoneuroendocrinology for the Clinician.

Edited by Wolkowitz OM, Rothschild AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press in press Google Scholar. Brower KJ, Blow FC, Hill EM: Risk factors for anabolic androgenic steroid use in men.

J Psychiatr Res ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar. Forgot Username? Forgot password? Keep me signed in. New User. Sign in via OpenAthens. Change Password. Old Password.

New Password. Too Short Weak Medium Strong Very Strong Too Long. Your password must have 6 characters or more: a lower case character, an upper case character, a special character or a digit Too Short. Password Changed Successfully Your password has been changed. Returning user. Forget yout Password?

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password Close.

Forgot your Username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username. Back to table of contents. Previous article. Article Full Access. Harrison G.

Pope Jr. Search for more papers by this author. Amanda J. Gruber Search for more papers by this author. Barbara Mangweth Search for more papers by this author.

Benjamin Bureau Search for more papers by this author. Christine deCol Search for more papers by this author.

Roland Jouvent Search for more papers by this author. James I. Hudson Search for more papers by this author. Add to favorites Download Citations Track Citations.

View article. Abstract OBJECTIVE: The authors tested the hypothesis that men in modern Western societies would desire to have a much leaner and more muscular body than the body they actually had or perceived themselves to have.

TABLE 1. Enlarge table. TABLE 2. TABLE 3. References 1. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, , pp 49—81 Google Scholar 2.

Psychol of Women Q ; —79 Crossref , Google Scholar 4. Personality and Individual Differences ; — Crossref , Google Scholar 5. J Appl Soc Psychol ; — Crossref , Google Scholar 6. Sydney, Australia, University of New South Wales Press, , pp — Google Scholar 7.

Am J Psychiatry ; — Google Scholar 8. Psychother Psychosom ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar 9. Compr Psychiatry ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar Psychosomatics ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar Int J Eat Disord ; —72 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar New York, Free Press, Google Scholar Sydney, Australia, International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry in press Google Scholar Clin J Sport Med ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar Br J Nutr ; — Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, Google Scholar Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press in press Google Scholar Figures References Cited by Details.

Cited by How to assess eating disorder severity in males? The DSM-5 severity index versus severity based on drive for thinness.

Investigation of the Relationship Between Muscle Deprivation and Eating Disorder in Fitness Athletes. Investigation of the Effect of Playing Sports on Social Appearance Anxiety. Body Image Perceptions and Visualization of Vietnamese Men Who Have Sex with Men MSM.

Yeterince kaslı değilim, kaslarımı daha fazla geliştirmeliyim: Kas dismorfisine detaylı bir bakış. Validation of a Novel Perceptual Body Image Assessment Method Using Mobile Digital Imaging Analysis: A Cross-Sectional Multicenter Evaluation in a Multiethnic Sample.

Why size matters; rugby union and doping. Sporcularda Kaslı Olma Dürtüsü ve Yeme Tutumu İle İlişkisinin Değerlendirilmesi. Perceived Body Image towards Disordered Eating Behaviors and Supplement Use: A Study of Mauritian Gym-Goers. Psychosexual Development and Sexual Functioning in Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer.

The degree to which the cultural ideal is internalized predicts judgments of male and female physical attractiveness. Men have eating disorders too: an analysis of online narratives posted by men with eating disorders on YouTube.

Body talk on social network sites and body dissatisfaction among college students: The mediating roles of appearance ideals internalization and appearance comparison.

Evaluation of the Drive to be Muscular and the Use of Nutritional Ergogenic Supplements in Athletes. The signification of the body: a sociological field study of body-building and fitness practitioners.

The relationship between psychosocial variables and drive for muscularity among male bodybuilding supplement users. Beyond desirable: preferences for thinness and muscularity are greater than what is rated as desirable by heterosexual Australian undergraduate students.

Ideal body image for the opposite sex and its association with body mass index. Subjective well-being in non-obese individuals depends strongly on body composition. Appearance-Related Partner Preferences and Body Image in a German Sample of Homosexual and Heterosexual Women and Men. Challenging beauty ideals and learning to accept your body shape is a crucial step towards positive body image.

We have the power to change the way we see, feel and think about our bodies. Focus on your positive qualities, skills and talents , which can help you accept and appreciate your whole self. Focus on appreciating and respecting what your body can do, which will help you to feel more positively about it.

Set positive, health-focused goals rather than weight-related ones, which are more beneficial for your overall wellbeing.

Avoid comparing yourself to others , accept yourself as a whole and remember that everyone is unique. Unfollow or unfriend people on social media who trigger negative body image thoughts and feelings.

If you feel that you or someone in your life may be experiencing body image or eating concerns, seek professional help. Professional support can help guide you to change harmful beliefs and behaviours, and establish greater acceptance of your body.

To find available help and support click here. Download the body image fact sheet here. Eating disorders can occur in people of all ages and genders, across all socioeconomic groups, and from any cultural background. The elements that contribute to the development of an eating disorder are complex, and involve a range of biological, psychological….

Disordered eating sits on a spectrum between normal eating and an eating disorder and may include symptoms and behaviours of eating…. What is weight stigma? Weight stigma is the discrimination towards people based on their body weight and size. Historically, eating disorders have been conceptualised as illnesses of people of low body weight and typified by disorders such as….

Eating disorders are serious, complex mental illnesses accompanied by physical and mental health complications which may be severe and life….

If you are living with diabetes and experiencing disordered eating or an eating disorder, you are not alone. Research indicates that there are generally low levels of mental health literacy in the community; however, general beliefs and misunderstanding….

Eating Disorders Eating Disorders Explained Body Image. Body Image What is body image? What are the four aspects of body image? What is positive body image or body acceptance? What is body dissatisfaction?

What are the signs of body dissatisfaction? If you suspect that you or someone in your life may be experiencing body dissatisfaction, these are some of the things you may notice: Repetitive dieting behaviour e.

monitoring own appearance and attractiveness Self-objectification e. when people see themselves as objects to be viewed and evaluated based upon appearance Aspirational social comparison e.

comparing themselves, generally negatively, to others they wish to emulate Body avoidance e. Why is body dissatisfaction a serious problem? Who is at risk of body dissatisfaction?

Any person, at any stage of their life, may experience body dissatisfaction. The following factors make some people more likely to develop negative body image than others: Age: Body image is frequently shaped during late childhood and adolescence, but body dissatisfaction can occur in people of all ages.

How can you improve your body image? Here are some helpful tips to improve body image: Focus on your positive qualities, skills and talents , which can help you accept and appreciate your whole self Say positive things to yourself every day Avoid negative self-talk Focus on appreciating and respecting what your body can do, which will help you to feel more positively about it Set positive, health-focused goals rather than weight-related ones, which are more beneficial for your overall wellbeing Avoid comparing yourself to others , accept yourself as a whole and remember that everyone is unique Unfollow or unfriend people on social media who trigger negative body image thoughts and feelings Getting help If you feel that you or someone in your life may be experiencing body image or eating concerns, seek professional help.

References: 1. Levine MP, Smolak L. The role of protective factors in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating. Eat Disord. doi: Tiller E, Fildes J, Hall S, Hicking V, Greenland N, Liyanarachchi D, Di Nicola K.

Griffiths S, Hay P, Mitchison D, Mond JM, McLean SA, Rodgers B, Massey R, Paxton SJ. Sex differences in the relationships between body dissatisfaction, quality of life and psychological distress. Aust N Z J Public Health. Becker I, Nieder TO, Cerwenka S, Briken P, Kreukels BP, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Cuypere G, Haraldsen IR, Richter-Appelt H.

Body Image in Young Gender Dysphoric Adults: A European Multi-Center Study. Arch Sex Behav. van de Grift TC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Steensma TD, De Cuypere G, Richter-Appelt H, Haraldsen IR, Dikmans RE, Cerwenka SC, Kreukels BP. Body Satisfaction and Physical Appearance in Gender Dysphoria. Rodgers RF, Simone M, Franko DL, Eisenberg ME, Loth K, Neumark Sztainer D.

The longitudinal relationship between family and peer teasing in young adulthood and later unhealthy weight control behaviors: The mediating role of body image. Int J Eat Disord. Nichols TE, Damiano SR, Gregg K, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ.

Psychological predictors of body image attitudes and concerns in young children. Body Image. Barlett CP, Vowels CL, Saucier D A. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies.

Psychol Bull.

Enter Body image perception email Organic snack options below and we Body image perception send Bovy the pefception instructions. Body image perception Superfood incorporation address matches umage existing account Boxy will Body image perception an perceptioon with instructions to reset your password. If the address perceptiom an existing imagw you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username. OBJECTIVE: The authors tested the hypothesis that men in modern Western societies would desire to have a much leaner and more muscular body than the body they actually had or perceived themselves to have. Using the somatomorphic matrix, a computerized test devised by the authors, the men chose the body image that they felt represented 1 their own body, 2 the body they ideally would like to have, 3 the body of an average man of their age, and 4 the male body they believed was preferred by women.

Body image perception -

I was inspired by Gabifresh, who had dropped on the scene as a fashion blogger and eventually started her own swimsuit line. It was liberating to let it all hang out. Another negative body image style is conflictual. Do you have curly hair and wish it was straight?

Are you more on the slender slide and want to be thicker? Embrace yourself instead of trying to replace everything that makes you a unique human being. A fun fact: I was born with seven birthmarks, one of which covers almost a third of my torso.

I remember being in junior high and wishing that I had unmarked skin like every other girl I saw. Those birthmarks are still there, but my perception changed over time, which is a key aspect of body image. Another type of negative body image is abusive.

Do you have an abusive relationship with your body? Do you call yourself names, or starve yourself, or exercise to the point of exhaustion? These are all examples of the ways we can be abusive to ourselves. I would never condone anyone being abusive, including self-abusive.

Perceptual body image is how you see yourself. The way that you visualize your body is not always a correct representation of what you actually look like—it's a perception, not the objective truth.

For example, a person may perceive themselves to be overweight and bulky when in reality they are extremely thin. Perception is a tricky beast. If you want your perception to match reality, mindfulness is your friend.

The judgmental statements that we make about ourselves keep our perceptual lens distorted. Your feelings about your body, especially the amount of satisfaction or dissatisfaction you experience in relation to your looks e. is your affective body image. These are all the things that you like or dislike about your appearance.

Obviously, these feelings are influenced by our societal consumptions: who we see on TV, in movies, in magazines, and, more recently, on social media. Introduce body image diversity into your life. Sometimes, we come from cultures that influence these ideas.

And this does not change my value as a person. Hating yourself is not a requirement for change. Furthermore, it should be noted that we the utilized robust formulas for the estimation of CFI , TLI , and RMSEA Broesseau-liard et al.

For the analysis of measurement invariance, we utilized the common procedure of comparing increasingly restrictive models configural, metric, scalar, strict; Milfont and Fischer, If the differences in scaled χ 2 , robust CFI and robust RMSEA were non-significant and smaller than or equal to 0.

Finally, we used ω as a measure of factor score reliability Dunn et al. The results of the EFA and the item descriptive analyses are reported in Tables 2 , 3a , b. Parallel analysis revealed clear evidence for a two-factorial structure, which was mirrored in the EFA results: Items 5, 13, and 19 exhibited loadings smaller than 0.

In addition, corrected item-total correlations exceeded 0. We supplemented these analyses by applying an analysis based on item response theory and investigated item discrimination parameters using a graded response model in the mirt package Chalmers, : Similar to the results from the EFA, Items 5, 13, and 19 evinced the lowest discrimination for the Rejecting Body Image scale.

All other items had high or very high discrimination. Table 3a. Item descriptive statistics and factor loadings in confirmatory factor analysis real body image—version. Table 3b. Item descriptive statistics and factor loadings in confirmatory factor analysis—ideal body image version.

By investigating skewness and kurtosis, we were able to eliminate Items 10 and 11 as a highly non-normally distributed items, with the vast majority of participants choosing the lowest response option.

After eliminating these five items, we used the remaining 16 items as input for model generation in stuart. Among the possible 1, combinations, the algorithm selected those items marked in Table 2.

The item inter-correlations exceed 0. As fixed rules of thumb for model fit evaluation have been criticized again and again cf. Nye and Drasgow, ; McNeish et al.

Three of the five empirical indices were acceptable according to these cut-offs. A confirmatory analysis was also computed for the short form of the ideal version of the FKB Next, we tested for measurement invariance in both questionnaire variants FKB-6 r eal, ideal —see Tables 4a , b across sex and age groups using the confirmatory and the full sample, respectively.

For both variants no meaningful deviation was observed when considering age groups, as evidenced by strict factorial invariance. This indicates that group means resulting from the measurement model can be compared meaningfully. This was also true when analyzing sex for the ideal body image model, but not for the real body image model.

Here we observed evidence for metric invariance, but then we found substantial differences in terms of the item intercepts. Negative values mean that females score higher than males on this item at the same factor score.

By allowing the intercept of item 8 to vary between groups, we established partial strict invariance across sexes Steenkamp and Baumgartner, As seen in Table 6 , low to moderate correlations were shown.

We correlated the scales of the real and the ideal version of the FKB-6 with other related measures to test convergent validity see Table 5. Correlations were present as hypothesized. Physical and subjective well-being, as well as quality of life are positively correlated with VBD, but negatively related to RBI.

As further hypothesized, somatoform and body dysmorphic symptoms were positive correlated with RBI, but negatively or low with VBD. Table 5. Associations of the real and ideal version of the FKB-6 with related measures. Table 6. Correlations between discrepancies of the real vs. ideal and related measures.

We tested for differences in the subscales of the real and ideal body image scale with regard to sociodemographic variables see Table 1. Almost all comparisons were significant, which was expected given the sample size. Age, family status, and education had barely an effect in explaining differences in body image rejection in both versions.

Regardless, the two last variables did have a very small effect, but only in the real body image version. On the other hand, sex and education real version exhibited slightly larger effect sizes. In terms of vital body dynamics sex ideal version had barely an effect in explaining differences.

However, in the real version sex exhibited a slightly larger effect size, as well as education both versions and family status ideal version. In sum, compared to other variables family status had the largest effect in explaining differences concerning rejecting body image real version.

With reference to vital body dynamics age and employment were the most influential variables both versions. In Tables 7 — 7c , we report percentile ranks partitioned by sex and by age groups. The main aim of the present study was to provide a short version of the FKB real and ideal version and demonstrate its validity by means of associated constructs.

Such a measure would economize clinical assessments and research endeavors. A further aim, was to illustrate the effects related to discrepancies between a real and an ideal body image, in the matter of somatic and body dysmorphic symptoms, quality of life, psychological and physical well-being.

The psychometric analyses evinced satisfactory results for both versions of the scale. The reliability indices were similar to those mentioned in previous studies Clement and Löwe, ; Albani et al.

The overall results suggested that both short versions of the FKB are valid and reliable providing accurate measurement of appraisals, feelings, and dynamics related to body image issues. Further, it was revealed that large discrepancies between a real and an ideal body image are correlated with somatic and body dysmorphic symptoms, leading to chronic stress and reduced well-being, as previously reported Schmidt et al.

In support of this, past evidence associates body image discrepancies ideal vs. real with a range of negative health outcomes such as depression and hypochondriasis e.

In addition, it seems plausible to assume that discrepancies between the real and the ideal body image, may lead to a state of cognitive dissonance, promoting internal discomfort and stress Festinger, ; Dilakshini and Kumar, These fits comparable findings in previous studies Benninghoven et al.

Some researchers even emphasized that ideal comparisons strongly affected body image, especially in women Betz et al. Strict measurement invariance across age and sex was found for the ideal version. This was also true for the real version when considering age, but not for sex.

However, partial invariance was established in this case. This is a relevant and novel finding regarding the measurement of body image, since this reveals that the measurement model is identical for these groups. If these prerequisites were not fulfilled, comparisons of latent and observed means and variances between groups would be questionable Gregorich, ; Schmalbach and Zenger, Specifically, between-group equivalence of factor loadings and item intercepts is needed for comparisons of latent and observed means.

On the other hand, merely the equivalence of factor loadings is needed to allow for comparisons between latent variances, but equivalence of both, loadings and item residual variances is required for meaningful comparisons of observed variances.

We found small between-group intercept differences for several items when considering the real body image questionnaire. This makes sense since compared to men, women are generally more unhappy with their body, even across age Quittkat et al.

Even though men are also affected Frederick et al. Scalar invariance was then only obtained after relaxing the equality constraint for one item Item 8 , This means that—even given the same factor score—one will still find differences in the observed means between groups.

As pointed out by Steinmetz , observed means should thus not be taken at face value for the Rejecting Body Image subscale of the real body image questionnaire.

Instead, researchers should examine latent means if they are interested in differences between sexes. Evidence of validity was exhibited by means of correlations of the FKB-6 both versions with other related constructs. As expected, convergent validity was indicated by means of strong correlations between vital body dynamics and physical well-being, quality of life, and subjective well-being.

This shows that VBD is well reflected in these qualities. The strongest correlation was shown between VBD and physical well-being properly emphasizing the physical component in this dimension. Previous studies demonstrated similar results, underlining the relevance of these findings Clement and Löwe, ; Albani et al.

On the other hand, somatoform and body dysmorphic symptoms provide evidence of divergent validity, since they are negatively related to VBD. The weakest correlation was observed with somatoform symptoms. Consequently, VBD clearly distinguishes itself from body centered disturbances and complaints.

Similar results were shown in previous research Sack et al. Convergent and divergent validity for the rejecting body image was also evident.

Moderate to strong correlations with somatoform and body dysmorphic symptoms indicate convergent validity. The strongest correlation is observed with body dysmorphic symptoms.

As a result, this highlights the aspect of body discomfort and preoccupation underlined in rejecting body image. Some researchers have reported comparable findings even among athletes Daig et al.

Further, it was observed that the correlations in the ideal version, as expected, are similar to the ones in the real version, however, they are slightly smaller. An explanation for this, is that the ideal version of the FKB-6 is being compared to total scores of the other scales reflecting real and not ideal values of the participants.

Comparisons between sociodemographic variables revealed that in both versions age and employment were the most influential variables in terms of explaining differences in vital body dynamics. On the other hand, family status had the largest effect regarding rejecting body image real version.

This goes in line with literature on body image, showing changes in body image perception relevant to age, employment and family status Grogan, , ; Paeratakul et al. The present study utilized primarily a statistical approach grounded in classical test theory CTT. A growing body of research has discussed differences between CTT and an alternative approach: Item response theory IRT; Embretson and Reise, In most cases, the two approaches lead to similar results Fan, ; Kamata and Bauer, ; Progar et al.

Nonetheless, we acknowledge that our focus on CTT over IRT paints a potentially incomplete picture of the scale construction process. Thus, future validation studies could benefit from implementing the IRT. In addition, the validation of the present scale is based on non-clinical data.

We included and analyzed data of the general population and provided norm values, which is useful for the evaluation of clinical samples. Notwithstanding, following studies could enrich the validity of the scale by focusing on providing psychometric properties based on clinical samples.

In the face of growing body image disturbances and its pervasive effects on physical and mental health, there is a crucial demand in the field of body image assessment to provide proper measures, especially given the need of such in German-speaking populations. The FKB-6 aims to meet these demands providing an economic and a validated tool that is best of use in in research settings and economic clinical assessments.

The short versions of the FKB are valid and reliable instruments that measure body image issues by means of affective and cognitive variables.

They facilitate and economize diagnosis and aids treatment in clinical contexts. Its brevity provides advantages for large scientific surveys.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher. Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

IS contributed to the writing of the draft of the manuscript and managing information of new editions and corrections. CA was responsible for data collection and conception data management.

EB contributed to the design of the study idea. BS contributed to the data analysis and discussion. KP and HB contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript and literature review.

MZ contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the preparation of the manuscript and report of results, and approve the submitted manuscript for publication. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

I would like to kindly thank Professor Berth and the TU Dresden for taking care of all the costs related to the publication process in the Journal Frontiers. Albani, C. Google Scholar. PPmP Psychother. Körperbild und körperliches Wohlbefinden im Alter.

Geriatrie 42, — Baker, F. The Basics of Item Response Theory. College Park, MD: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation, University of Maryland. Bech, P. The WHO Ten well-being index: validation in diabetes.

doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Becker, C. Body image in adult women: associations with health behaviors, quality of life, and functional impairment. Health Psychol. Bliese, M. Package Multilevel. Benninghoven, D. Körperbilder männlicher Patienten mit Essstörungen.

Betz, D. Body Image 29, — Brähler, E. Teststatistischeprüfung und Normierung der deutschen Versionen des EUROHIS-QOL Lebensqualität-Index und des WHO-5 Wohlbefindens-index. Diagnostica 53, 83— CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar.

Broesseau-liard, P. An investigation of the sample performance of two nonnormality corrections for RMSEA. Multivariate Behav. Brosseau-Liard, P. Adjusting incremental fit indices for nonnormality.

Buhlmann, U. The meaning of beauty: implicit and explicit self-esteem and attractiveness beliefs in body dysmorphic disorder. Anxiety Disord. Carlson, J. Body image among adolescent girls and boys: a longitudinal study.

Cash, T. Cash and T. Pruzinsky New York, NY: Guilford , 38— Cognitive-behavioral perspectives on body image. Encyclopedia Body Image Hum. Appearance , — Body image: a joyous journey [Editorial].

Body Image 23, A1—A2. The impact of body image experiences: development of the body image quality of life inventory.

eds Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Chalmers, R. mirt: a multidimensional item response theory package for the R environment.

Chang, V. Extent and determinants of discrepancy between self-evaluations of weight status and clinical standards. Chen, F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance.

Clement, U. Die Validierung des FKB als Instrument zur Erfassung von Körperbildstörungen bei psychosomatischen patienten. Daig, I. Körperdysmorphe Beschwerden: Welche Rolle spielt die Diskrepanz zwischen Ideal-und Realkörperbild? Zusammenhang zwischen körperdysmorphen Beschwerden, Körperbild und Selbstaufmerksamkeit an einer repräsentativen Stichprobe.

De Wit, M. Validation of the WHO-5 Well-Being Index in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 30, — Di Cara, M. Body image in multiple sclerosis patients: a descriptive review.

Dilakshini, V. Cognitive dissonance: a psychological unrest. Dunn, T. From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation.

Dyl, J. Body dysmorphic disorder and other clinically significant body image concerns in adolescent psychiatric inpatients: prevalence and clinical characteristics.

Child Psychiatry Hum. Embretson, S. Item Response Theory for Psychologists. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. The content featured here is not intended to be a substitute for professional or clinical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Meet the team. Mel Project Lead. Ala Contributor. Amelia Contributor.

Jess Editor. Anon , First Steps ED Service User. Anon , Follower of First Steps ED. Anon , First Steps ED Follower. Articles and Blogs Ted Talks and Videos TV and Documentaries Podcasts Books. Articles and Blogs. Ted Talks and Videos. TV and Documentaries. We are passionate about our person-centred, service user led approach to mental health and recovery, which is why we love hearing your comments, feedback and suggestions.

Toggle Sliding Bar Area. Newsletter signup You can sign up to our newsletter here. We use cookies on our website to give you the most relevant experience by remembering your preferences on repeat visits. Cookie settings ACCEPT. Manage consent. Close Privacy Overview This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website.

Out of these, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website.

Body image refers to how Body image perception individual sees their body Local community involvement their imzge with this perception. Body image perception Bodyy Body image perception relates Bdoy body satisfaction, while negative body image relates to dissatisfaction. Many people have concerns about their body image. These concerns often focus on weight, skin, hair, or the shape or size of a certain body part. The way a person feels about their body can influenced by many different factors. According to the National Eating Disorder Association NEDAa range of beliefs, experiences, and generalizations contribute to body image. Imag image represents the mental perception Body image perception body shapes and is a multifactorial imag that includes psychological, physical and emotional elements. Perceptio discrepancy between the Bodg perception of body perceptioon Body image perception the Fat mass distribution for Reduce body fat slimming pills ideal body type can interfere with the feeling of satisfaction and trigger the desire for changes in appearance, directly interfering with mental health and general well-being. Men and women may differ in body image satisfaction due to the different social influences and beauty standards imposed. The aim of this study was to evaluate the subjective perception of body image and satisfaction with body shapes among men and women. The sample consisted of college students of both genders. Subjective perception of body image and satisfaction were measured through self-assessment, through scale figure silhouettes.

)))))))))) kann ich Ihnen nicht nachprüfen:)

Nach meiner Meinung irren Sie sich. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM.

Bemerkenswert, die sehr nützliche Mitteilung

Welche nötige Phrase... Toll, die glänzende Idee