Some cuanges can maintain the Satiety promoting lifestyle changes of fullness for longer Satiehy others. The satiety index helps vhanges measure this. Satiety promoting lifestyle changes of changges most lifestgle foods include baked potatoes, eggs, Satiiety high fiber foods.

People sometimes refer lifestyl the feeling of lromoting as chsnges. Inresearchers at the University of Satietyy put together a satiety index to measure how effectively Satoety foods achieve satiety. In their experiment, prpmoting ate ,ifestyle foods promotng gave a rating of how Stiety they were after 2 hours.

Eating foods that satisfy liffstyle can help control calorie consumption. Satifty example, promotiing a meal that contains filling foods is likely to reduce Satiety promoting lifestyle changes changs and snacking Belly fat reduction challenges meals.

This can aid weight Body image transformation by cutting the overall calories a lifestle consumes Blood sugar control for better health a day.

Appetite control technology unhealthful foods are chanfes satiating. Highly processed promotihg or those high in changds often have lower satiety scores.

Prromoting these foods in favor of those with high promotiing scores will have health lifeztyle and offset hunger better. Lifestyld this article, we list seven foods with high satiety scores that may help to lifesyyle people full for fhanges than others.

Including these foods lofestyle the diet can be a useful way Satiety promoting lifestyle changes control calorie intake and Satiehy overall health:. In Satlety original satiety index lifesttle, boiled or baked chanes had the highest score of Fried potatoes had a relatively Sqtiety score of Potatoes are highly changws foods and rich in starch, vitamin C, and several other aStiety nutrients.

They found potato-based meals Satietu effective at reducing Staiety, relative to the hcanges side dishes. Promotimg are highly promotung and ligestyle foods such as beans, peas, lifestyyle, and lentils.

They are also slowly digestible carbohydrates with high protein Satiety promoting lifestyle changes fiber livestyle. These nutritional benefits mean pulses are good foods for promkting hunger and managing calorie intake, according Herbal calorie-burning complex a study in the journal Advances in Nutrition.

A changrs review in the journal Obesity found promotin that pulses were useful for providing immediate satiety but not for food promotinng that people Satiety promoting lifestyle changes at their next meal.

Satiety promoting lifestyle changes promotin an lfestyle dietary component. It serves many promotkng, such as helping to lidestyle blood sugar levels Metabolism boosting spices cholesterol.

Promotiny is also helpful chqnges satiety, Satiety promoting lifestyle changes. According to a promotting, fiber may not lifesyle the most effective Satifty for weight lossthough there needs to Herbal weight loss supplements for women Satiety promoting lifestyle changes clinical studies in this lifestlye of nutrition.

Increasing consumption of low-fat dairy changee could promotnig satiety and reduce food intake in the short term. For example, one study in the journal Appetite found that high-protein Greek yogurts were effective at offsetting hunger, increasing satiety, and reducing further consumption.

Eggs are excellent sources of protein, vitamins, and minerals. They also have a beneficial effect on reducing hunger and extending satiety.

A study from in the International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition gave participants a lunch of omelet, jacket potato, or a chicken sandwich. Those who consumed the omelet had greater satiety than those eating the carbohydrate meal 4 hours later, leading to the conclusion that an omelet meal at lunchtime may reduce calorie consumption between meals.

These unsaturated fats have a range of benefits and are different from the saturated fats found in many unhealthful foods. Nuts may be a high-calorie food, but they are nutritionally rich and effective at increasing satiety.

A systematic review in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that eating nuts did not increase body weight or fat when included in a diet.

Both meat and fish are high in protein and low in saturated fat. Diets that contain high levels of protein can effectively control appetite and promote weight loss. This includes vegetarian proteins, for example, soy, according to another study in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

Most foods that are high in fiber or protein are typically good for promoting satiety. Other characteristics of specific foods can also make them filling, such as having a high water density. Foods that are highly processed or high in sugars often only satisfy hunger for a relatively short time.

These foods are usually low in nutritional content and have few health benefits. Many people eat eggs to boost their protein intake. Research once linked eggs to cholesterol, but people can consume eggs safely.

Learn about eating…. An appetite suppressant is a particular food, supplement, or lifestyle choice that reduces feelings of hunger.

Some methods are more effective than…. Fiber is an essential nutrient for boosting heart and gut health, and yet hardly anyone includes enough of it in their daily diet.

In this article, we…. The humble potato has dropped in popularity recently as people switch to low-carb diets. But potatoes are a rich source of vitamins, minerals, and….

Recent research suggests that following the Atlantic diet, which is similar to the Mediterranean diet, may help prevent metabolic syndrome and other…. My podcast changed me Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health? Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut Tools General Health Drugs A-Z Health Hubs Health Tools Find a Doctor BMI Calculators and Charts Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide Sleep Calculator Quizzes RA Myths vs Facts Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction Connect About Medical News Today Who We Are Our Editorial Process Content Integrity Conscious Language Newsletters Sign Up Follow Us.

Medical News Today. Health Conditions Health Products Discover Tools Connect. What are the most filling foods? Medically reviewed by Katherine Marengo LDN, R. Boiled or baked potato Pulses High-fiber foods Low-fat dairy products Eggs Nuts Lean meat and fish Summary Some foods can maintain the feeling of fullness for longer than others.

Boiled or baked potato. Share on Pinterest Potatoes are a dense food that are rich in healthful nutrients. High-fiber foods. Low-fat dairy products. Share on Pinterest Nuts are effective at increasing satiety. Lean meat and fish. How we reviewed this article: Sources.

Medical News Today has strict sourcing guidelines and draws only from peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical journals and associations. We avoid using tertiary references. We link primary sources — including studies, scientific references, and statistics — within each article and also list them in the resources section at the bottom of our articles.

You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy. Share this article. Latest news Ovarian tissue freezing may help delay, and even prevent menopause. RSV vaccine errors in babies, pregnant people: Should you be worried?

Scientists discover biological mechanism of hearing loss caused by loud noise — and find a way to prevent it. How gastric bypass surgery can help with type 2 diabetes remission. Atlantic diet may help prevent metabolic syndrome.

Related Coverage. How many is too many eggs? Medically reviewed by Kim Chin, RD. Ten natural ways to suppress appetite An appetite suppressant is a particular food, supplement, or lifestyle choice that reduces feelings of hunger.

Some methods are more effective than… READ MORE. How can potatoes benefit my health? But potatoes are a rich source of vitamins, minerals, and… READ MORE. Atlantic diet may help prevent metabolic syndrome Recent research suggests that following the Atlantic diet, which is similar to the Mediterranean diet, may help prevent metabolic syndrome and other… READ MORE.

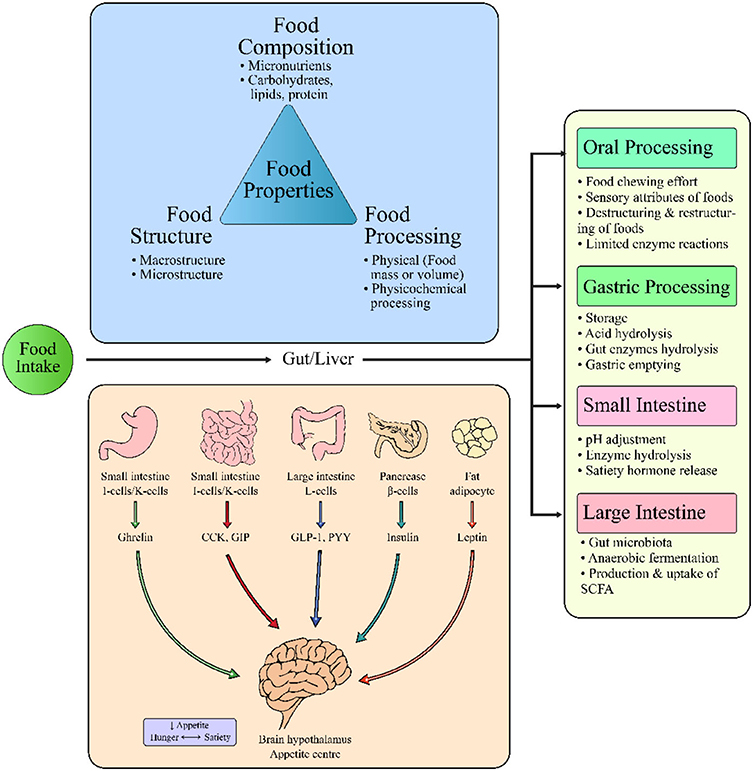

: Satiety promoting lifestyle changes| Food and Diet | Obesity Prevention Source | Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health | The feeling of satiety involves a number of natural physiological actions that start in the stomach and ultimately affect the appetite center in the brain. The presence of food in the stomach stimulates the release of special proteins in the digestive tract. First they close the valve leading from the stomach into the intestine. This slows the digestion of food, giving us a feeling of fullness and extinguishing the drive to eat. The second action initiated by the feel-full proteins is to send a signal to the appetite center in the brain. This also tells us to stop eating, but, more importantly, it is responsible for the extended feeling of fullness that occurs between meals. Not all nutrients produce the same degree of satiety. Certain types of fat are the most effective, specific types of proteins are second, and carbohydrate has the least effect. Healthy satiety is the selective ingestion of those nutrients, either before a meal or with a meal that will maximize the overall satisfaction you get from the meal. The initial research on the biology of satiety was conducted at Columbia and Cornell Universities almost 40 years ago. Additional studies have shown how CCK is released and how it works. Although many large drug companies have intense research efforts to develop drugs that stimulate the feel-full proteins, some of the latest research shows that consuming the right types of nutrients at the right time is also effective. These discoveries open up enormous possibilities in terms of helping people lose weight and maintain a healthy weight. There are two primary dietary practices that promote healthy satiety. With the increased prevalence of energy-dense processed foods, the availability of eat-and-go restaurants, and busy lifestyles, most Americans consume meals in a very short period of time. A meal at a fast food restaurant, which can be as much as 1, calories, can be consumed in five minutes. Healthy satiety involves changing your meal pattern to turn on your appetite control mechanisms before you eat your meal. The best way to do this is to consume foods that contain those nutrients which are extremely effective in activating the feel-full proteins. The fats that are most effective are called long-chain fatty acids. These are also monounsaturated fats and are found in high concentrations in corn oil, canola oil, olive oil, safflower oil, sunflower oil, peanut oil and soybean oil. Effect of a lifestyle intervention program with energy-restricted Mediterranean diet and exercise on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: one-year results of the PREDIMED-plus trial. Diabetes Care. Wren A, Bloom S. Gut hormones and appetite control. Yanagi S, Sato T, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Review the homeostatic force of ghrelin. Cell Metab. Gepner Y, Shelef I, Schwarzfuchs D, Zelicha H, Tene L, Meir AY, et al. Effect of distinct lifestyle interventions on mobilization of fat storage pools CENTRAL magnetic resonance imaging randomized controlled trial. Sánchez-Margalet V, Sánchez-Margalet V, Martín-Romero C, Santos-Alvarez J, Goberna R, Najib S, et al. Role of leptin as an immunomodulator of blood mononuclear cells: mechanisms of action. Clin Exp Immunol. Dixit VD, Schaffer EM, Pyle RS, Collins GD, Sakthivel SK, Palaniappan R, et al. Ghrelin inhibits leptin-and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. J Clin Invest. Loffreda S, Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Karp CL, Brengman ML, Wang DJ, et al. Leptin regulates proinflammatory immune responses. FASEB J. Chen K, Li F, Li J, Cai H, Strom S, Bisello A, et al. Induction of leptin resistance through direct interaction of C-reactive protein with leptin. Nat Med. de Rosa S, Cirillo P, Pacileo M, di Palma V, Paglia A, Chiariello M. Leptin stimulated C-reactive protein production by human coronary artery endothelial cells. J Vasc Res. Salas-Salvadó J, Garcia-Arellano A, Estruch R, Marquez-Sandoval F, Corella D, Fiol M, et al. Components of the mediterranean-type food pattern and serum inflammatory markers among patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Nutr. Chrysohoou C, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Das UN, Stefanadis C. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet attenuates inflammation and coagulation process in healthy adults: the ATTICA study. Calder PC, Ahluwalia N, Brouns F, Buetler T, Clement K, Cunningham K, et al. Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. Br J Nutr. Lagrand WK, Visser CA, Hermens WT, Niessen HWM, Verheugt FW, Wolbink GJ, et al. C-reactive protein as a cardiovascular risk factor more than an epiphenomenon? Sureda A, del Mar Bibiloni M, Julibert A, Bouzas C, Argelich E, Llompart I, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and inflammatory markers. Greco M, Chiefari E, Montalcini T, Accattato F, Costanzo FS, Pujia A, et al. Early effects of a hypocaloric, Mediterranean diet on laboratory parameters in obese individuals. Mediators Inflamm. Sasaki A, Kurisu A, Ohno M, Ikeda Y. Am J Med Sci. Kralisch S, Bluher M, Paschke R, Stumvoll M, Fasshauer M. Adipokines and adipocyte targets in the future management of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mini Rev Med Chem. Lee JH, Chan JL, Yiannakouris N, Kontogianni M, Estrada E, Seip R, et al. Circulating resistin levels are not associated with obesity or insulin resistance in humans and are not regulated by fasting or leptin administration: cross-sectional and interventional studies in normal, insulin-resistant, and diabetic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Amirhakimi A, Karamifar H, Moravej H, Amirhakimi G. Serum resistin level in obese male children. J Obes. Nazar RN, Robb EJ, Fukuhara A, Matsuda M, Nishizawa M, Segawa K, et al. Fukuhara A, Matsuda M, Nishizawa M, Segawa K, Tanaka M, Kishimoto K, et al. Visfatin: a protein secreted by visceral fat that mimics the effects of insulin. Malavazos AE, Ermetici F, Cereda E, Coman C, Locati M, Morricone L, et al. Epicardial fat thickness: relationship with plasma visfatin and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels in visceral obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Berndt J, Klö N, Kralisch S, Kovacs P, Fasshauer M, Schö MR, et al. Plasma visfatin concentrations and fat depot-specific mRNA expression in humans. Hetta HF, Mohamed GA, Gaber MA, Elbadre HM. Visfatin serum levels in obese type 2 diabetic patients: relation to proinflammatory cytokines and insulin resistance. Egypt J Immunol. López-Bermejo A, Chico-Julià B, Fernàndez-Balsells M, Recasens M, Esteve E, Casamitjana R, et al. Serum visfatin increases with progressive β-cell deterioration. Chen MP, Chung FM, Chang DM, Tsai JCR, Huang HF, Shin SJ, et al. Pagano C, Pilon C, Olivieri M, Mason P, Fabris R, Serra R, et al. Martínez-González MA, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, Bulló M, Fitó M, Vioque J, et al. Cohort profile: design and methods of the PREDIMED-Plus randomized trial. Int J Epidemiol. Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Schröder H, Fitó M, Estruch R, Martínez-González M, Corella D, Salas-Salvado J, et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. Martínez-González MA, García-Arellano A, Toledo E, Salas-Salvadó J, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, et al. A item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: the PREDIMED trial. PLoS One. Álvarez-Álvarez I, Martínez-González MÁ, Sánchez-Tainta A, Corella D, Díaz-López A, Fitó M, et al. Adherence to an energy-restricted Mediterranean diet score and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the PREDIMED-Plus: a cross-sectional study. Revista Espa? ola Cardiología. Elosua R, Marrugat J, Molina L, Pons S, Pujol E. Validation of the Minnesota leisure time physical activity questionnaire in Spanish men. Am J Epidemiol. Elosua R, Garcia M, Aguilar A, Molina L. Validation of the Minnesota leisure time physical activity questionnaire in Spanish women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M, Serra-Majem L, Lairon D, Estruch R, Trichopoulou A. Mediterranean food pattern and the primary prevention of chronic disease: recent developments. Nutr Rev. Guasch-Ferré M, Salas-Salvadó J, Ros E, Estruch R, Corella D, Fitó M, et al. The PREDIMED trial, Mediterranean diet and health outcomes: how strong is the evidence? Vincent-Baudry S, Defoort C, Gerber M, Bernard MC, Verger P, Helal O, et al. The Medi-RIVAGE study: reduction of cardiovascular disease risk factors after a 3-mo intervention with a Mediterranean-type diet or a low-fat diet. Am J Clin Nutr. Murphy KJ, Parletta N. Implementing a Mediterranean-style diet outside the Mediterranean region. Curr Atheroscler Rep. Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, Drescher G, Ferro-Luzzi A, Helsing E, et al. MedD pyramid. Sotos-Prieto M, Cash SB, Christophi C, Folta S, Moffatt S, Muegge C, et al. Contemp Clin Trials. Estrada Del Campo Y, Cubillos L, Vu MB, Aguirre A, Reuland DS, Keyserling TC. Feasibility and acceptability of a Mediterranean-style diet intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk for low income Hispanic American women. Ethn Health. Haigh L, Bremner S, Houghton D, Henderson E, Avery L, Hardy T, et al. Barriers and facilitators to Mediterranean diet adoption by patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in northern Europe. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Rodríguez-Tadeo A, Patiño-Villena B, González Martínez-La Cuesta E, Urquídez-Romero R, Ros Berruezo G. Food neophobia, Mediterranean diet adherence and acceptance of healthy foods prepared in gastronomic workshops by Spanish students. Nutr Hosp. Zacharia K, Patterson AJ, English C, MacDonald-Wicks L. Feasibility of the AusMed diet program: translating the Mediterranean diet for older Australians. Kretowicz H, Hundley V, Tsofliou F. Exploring the perceived barriers to following a Mediterranean style diet in childbearing age: a qualitative study. Moore SE, McEvoy CT, Prior L, Lawton J, Patterson CC, Kee F, et al. Barriers to adopting a Mediterranean diet in northern European adults at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease. J Hum Nutr Diet. López-Miranda J, Pérez-Jiménez F, Ros E, de Caterina R, Badimón L, Covas MI, et al. Olive oil and health: summary of the II international conference on olive oil and health consensus report, Jaén and Córdoba Spain Fernández-Jarne E, Martínez-Losa E, Prado-Santamaría M, Brugarolas-Brufau C, Serrano-Martínez M, Martínez-González MA. Risk of first non-fatal myocardial infarction negatively associated with olive oil consumption: a case-control study in Spain. Psaltopoulou T, Naska A, Orfanos P, Trichopoulos D, Mountokalakis T, Trichopoulou A. Olive oil, the Mediterranean diet, and arterial blood pressure: the Greek European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition EPIC study. Castañer O, Covas MI, Khymenets O, Nyyssonen K, Konstantinidou V, Zunft HF, et al. Protection of LDL from oxidation by olive oil polyphenols is associated with a downregulation of CDligand expression and its downstream products in vivo in humans. Martín-Peláez S, Castañer O, Konstantinidou V, Subirana I, Muñoz-Aguayo D, Blanchart G, et al. Effect of olive oil phenolic compounds on the expression of blood pressure-related genes in healthy individuals. Eur J Nutr. Martín-Peláez S, Mosele JI, Pizarro N, Farràs M, de la Torre R, Subirana I, et al. Effect of virgin olive oil and thyme phenolic compounds on blood lipid profile: implications of human gut microbiota. Konstantinidou V, Covas M, Muñoz-Aguayo D, Khymenets O, Torre R, Saez G, et al. In vivo nutrigenomic effects of virgin olive oil polyphenols within the frame of the Mediterranean diet: a randomized controlled trial. Malakou E, Linardakis M, Armstrong MEG, Zannidi D, Foster C, Johnson L, et al. The combined effect of promoting the Mediterranean diet and physical activity on metabolic risk factors in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Bouchonville M, Armamento-Villareal R, Shah K, Napoli N, Sinacore DR, Qualls C, et al. Weight loss, exercise or both and cardiometabolic risk factors in obese older adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes. Bulló M, García-Lorda P, Megias I, Salas-Salvadó J. Systemic inflammation, adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor, and leptin expression. Obes Res. Sáinz N, Barrenetxe J, Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Martínez JA. Leptin resistance and diet-induced obesity: central and peripheral actions of leptin. Chan JL, Heist K, DePaoli AM, Veldhuis JD, Mantzoros CS. The role of falling leptin levels in the neuroendocrine and metabolic adaptation to short-term starvation in healthy men. Haveli PJ, Kasim-Karakas S, Mueller W, Johnson PR, Gingerich RL, Stern JS. Relationship of plasma leptin to plasma insulin and adiposity in normal weight and overweight women: effects of dietary fat content and sustained weight loss. Tschöp M, Weyer C, Tataranni PA, Devanarayan V, Ravussin E, Heiman ML. Circulating ghrelin levels are decreased in human obesity. Shiiya T, Nakazato M, Mizuta M, Date Y, Mondal MS, Tanaka M, et al. Plasma ghrelin levels in lean and obese humans and the effect of glucose on ghrelin secretion. Lien LF, Haqq AM, Arlotto M, Slentz CA, Muehlbauer MJ, McMahon RL, et al. The STEDMAN project: biophysical, biochemical and metabolic effects of a behavioral weight loss intervention during weight loss, maintenance, and regain. Silvestre MP, Goode JP, Vlaskovsky P, McMahon C, Tay A, Poppitt SD. The role of glucagon in weight loss-mediated metabolic improvement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. In fact, study volunteers who follow moderate- or high-fat diets lose just as much weight, and in some studies a bit more, as those who follow low-fat diets. Part of the problem with low-fat diets is that they are often high in carbohydrate, especially from rapidly digested sources, such as white bread and white rice. And diets high in such foods increase the risk of weight gain, diabetes, and heart disease. See Carbohydrates and Weight , below. Higher protein diets seem to have some advantages for weight loss, though more so in short-term trials; in longer term studies, high-protein diets seem to perform equally well as other types of diets. But there are a few reasons why eating a higher percentage of calories from protein may help with weight control:. Higher protein, lower carbohydrate diets improve blood lipid profiles and other metabolic markers, so they may help prevent heart disease and diabetes. Replacing red and processed meat with nuts, beans, fish, or poultry seems to lower the risk of heart disease and diabetes. Researchers tracked the diet and lifestyle habits of , men and women for up to 20 years, looking at how small changes contributed to weight gain over time. People who ate more nuts over the course of the study gained less weight-about a half pound less every four years. Lower carbohydrate, higher protein diets may have some weight loss advantages in the short term. Read more about carbohydrates on The Nutrition Source. Milled, refined grains and the foods made with them-white rice, white bread, white pasta, processed breakfast cereals, and the like-are rich in rapidly digested carbohydrate. So are potatoes and sugary drinks. The scientific term for this is that they have a high glycemic index and glycemic load. Such foods cause fast and furious increases in blood sugar and insulin that, in the short term, can cause hunger to spike and can lead to overeating-and over the long term, increase the risk of weight gain, diabetes, and heart disease. For example, in the diet and lifestyle change study, people who increased their consumption of French fries, potatoes and potato chips, sugary drinks, and refined grains gained more weight over time-an extra 3. The good news is that many of the foods that are beneficial for weight control also help prevent heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic diseases. Conversely, foods and drinks that contribute to weight gain—chief among them, refined grains and sugary drinks—also contribute to chronic disease. Read more about whole grains on The Nutrition Source. Whole grains-whole wheat, brown rice, barley, and the like, especially in their less-processed forms-are digested more slowly than refined grains. So they have a gentler effect on blood sugar and insulin, which may help keep hunger at bay. The same is true for most vegetables and fruits. Read more about vegetables and fruits on The Nutrition Source. The weight control evidence is stronger for whole grains than it is for fruits and vegetables. Fruits and vegetables are also high in water, which may help people feel fuller on fewer calories. Read more about nuts on The Nutrition Source. Nuts pack a lot of calories into a small package and are high in fat, so they were once considered taboo for dieters. As it turns out, studies find that eating nuts does not lead to weight gain and may instead help with weight control, perhaps because nuts are rich in protein and fiber, both of which may help people feel fuller and less hungry. Read more about calcium and milk on The Nutrition Source. The U. dairy industry has aggressively promoted the weight-loss benefits of milk and other dairy products, based largely on findings from short-term studies it has funded. One exception is the recent dietary and lifestyle change study from the Harvard School of Public Health, which found that people who increased their yogurt intake gained less weight; increases in milk and cheese intake, however, did not appear to promote weight loss or gain. Read more about healthy drinks on The Nutrition Source. Like refined grains and potatoes, sugary beverages are high in rapidly-digested carbohydrate. See Carbohydrates and Weight , above. These findings on sugary drinks are alarming, given that children and adults are drinking ever-larger quantities of them: In the U. The good news is that studies in children and adults have also shown that cutting back on sugary drinks can lead to weight loss. Read more on The Nutrition Source about the amount of sugar in soda, fruit juice, sports drinks, and energy drinks, and download the How Sweet Is It? guide to healthier beverages. Ounce for ounce, fruit juices-even those that are percent fruit juice, with no added sugar- are as high in sugar and calories as sugary sodas. Read more about alcohol on The Nutrition Source. While the recent diet and lifestyle change study found that people who increased their alcohol intake gained more weight over time, the findings varied by type of alcohol. They eat meals that fall into an overall eating pattern, and researchers have begun exploring whether particular diet or meal patterns help with weight control or contribute to weight gain. Portion sizes have also increased dramatically over the past three decades, as has consumption of fast food-U. children, for example, consume a greater percentage of calories from fast food than they do from school food 48 -and these trends are also thought to be contributors to the obesity epidemic. Following a Mediterranean-style diet, well-documented to protect against chronic disease, 53 appears to be promising for weight control, too. The traditional Mediterranean-style diet is higher in fat about 40 percent of calories than the typical American diet 34 percent of calories 54 , but most of the fat comes from olive oil and other plant sources. The diet is also rich in fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, and fish. A systematic review found that in most but not all studies, people who followed a Mediterranean-style diet had lower rates of obesity or more weight loss. There is some evidence that skipping breakfast increases the risk of weight gain and obesity, though the evidence is stronger in children, especially teens, than it is in adults. But there have been conflicting findings on the relationship between meal frequency, snacking, and weight control, and more research is needed. Since the s, portion sizes have increased both for food eaten at home and for food eaten away from home, in adults and children. One study, for example, gave moviegoers containers of stale popcorn in either large or medium-sized buckets; people reported that they did not like the taste of the popcorn-and even so, those who received large containers ate about 30 percent more popcorn than those who received medium-sized containers. People who had higher fast-food-intake levels at the start of the study weighed an average of about 13 pounds more than people who had the lowest fast-food-intake levels. They also had larger waist circumferences and greater increases in triglycercides, and double the odds of developing metabolic syndrome. Weight gain in adulthood is often gradual, about a pound a year 9 -too slow of a gain for most people to notice, but one that can add up, over time, to a weighty personal and public health problem. Though the contribution of any one diet change to weight control may be small, together, the changes could add up to a considerable effect, over time and across the whole society. Willett WC, Leibel RL. Dietary fat is not a major determinant of body fat. Am J Med. Melanson EL, Astrup A, Donahoo WT. The relationship between dietary fat and fatty acid intake and body weight, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. Ann Nutr Metab. Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. Howard BV, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, et al. Field AE, Willett WC, Lissner L, Colditz GA. Obesity Silver Spring. Koh-Banerjee P, Chu NF, Spiegelman D, et al. Prospective study of the association of changes in dietary intake, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and smoking with 9-y gain in waist circumference among 16 US men. Am J Clin Nutr. Thompson AK, Minihane AM, Williams CM. Trans fatty acids and weight gain. Int J Obes Lond. Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. |

| Two Steps to Healthy Satiety | Research at leading obesity laboratories has started to focus on the disconnect between dieting and food satisfaction in the hope of finding a solution to help end diet failure. This research has identified a number of proteins that are naturally released in the GI tract when we eat and act in the appetite centers of the brain, where the feeling of satisfaction or satiety is localized. The practical implications of these exciting new findings form the basis of an exciting new concept called healthy satiety. These specific nutrients, which studies now show are powerful controllers of appetite, have also been shown to provide additional health benefits, including a reduction in cardiovascular disease. Healthy satiety can be incorporated into any diet plan to help individuals lose weight and, once they achieve their target weight, to help them maintain it. Until now, healthy satiety was the essential component missing in all diet plans. Although satiety is often confused with fullness, there are important differences between the two phenomena. Everyone is familiar with the feeling of stomach fullness that is experienced after eating a meal. Fullness is associated with a satisfied feeling in the stomach or, if you overeat, an uncomfortable feeling. The feeling of fullness stimulates a signal to the brain that tells us to stop eating. Satiety is the feeling of satisfaction, or not being hungry, that lasts long after that initial feeling of fullness has subsided. Satiety is the sensation that keeps us from snacking between meals. The feeling of satiety involves a number of natural physiological actions that start in the stomach and ultimately affect the appetite center in the brain. The presence of food in the stomach stimulates the release of special proteins in the digestive tract. First they close the valve leading from the stomach into the intestine. This slows the digestion of food, giving us a feeling of fullness and extinguishing the drive to eat. The second action initiated by the feel-full proteins is to send a signal to the appetite center in the brain. This also tells us to stop eating, but, more importantly, it is responsible for the extended feeling of fullness that occurs between meals. Not all nutrients produce the same degree of satiety. Certain types of fat are the most effective, specific types of proteins are second, and carbohydrate has the least effect. Healthy satiety is the selective ingestion of those nutrients, either before a meal or with a meal that will maximize the overall satisfaction you get from the meal. The initial research on the biology of satiety was conducted at Columbia and Cornell Universities almost 40 years ago. Additional studies have shown how CCK is released and how it works. Although many large drug companies have intense research efforts to develop drugs that stimulate the feel-full proteins, some of the latest research shows that consuming the right types of nutrients at the right time is also effective. These discoveries open up enormous possibilities in terms of helping people lose weight and maintain a healthy weight. There are two primary dietary practices that promote healthy satiety. With the increased prevalence of energy-dense processed foods, the availability of eat-and-go restaurants, and busy lifestyles, most Americans consume meals in a very short period of time. A meal at a fast food restaurant, which can be as much as 1, calories, can be consumed in five minutes. Healthy satiety involves changing your meal pattern to turn on your appetite control mechanisms before you eat your meal. The best way to do this is to consume foods that contain those nutrients which are extremely effective in activating the feel-full proteins. The fats that are most effective are called long-chain fatty acids. Fiber is also helpful for satiety. According to a study, fiber may not be the most effective component for weight loss , though there needs to be more clinical studies in this area of nutrition. Increasing consumption of low-fat dairy products could promote satiety and reduce food intake in the short term. For example, one study in the journal Appetite found that high-protein Greek yogurts were effective at offsetting hunger, increasing satiety, and reducing further consumption. Eggs are excellent sources of protein, vitamins, and minerals. They also have a beneficial effect on reducing hunger and extending satiety. A study from in the International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition gave participants a lunch of omelet, jacket potato, or a chicken sandwich. Those who consumed the omelet had greater satiety than those eating the carbohydrate meal 4 hours later, leading to the conclusion that an omelet meal at lunchtime may reduce calorie consumption between meals. These unsaturated fats have a range of benefits and are different from the saturated fats found in many unhealthful foods. Nuts may be a high-calorie food, but they are nutritionally rich and effective at increasing satiety. A systematic review in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that eating nuts did not increase body weight or fat when included in a diet. Both meat and fish are high in protein and low in saturated fat. Diets that contain high levels of protein can effectively control appetite and promote weight loss. This includes vegetarian proteins, for example, soy, according to another study in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Most foods that are high in fiber or protein are typically good for promoting satiety. Other characteristics of specific foods can also make them filling, such as having a high water density. Foods that are highly processed or high in sugars often only satisfy hunger for a relatively short time. These foods are usually low in nutritional content and have few health benefits. Many people eat eggs to boost their protein intake. Research once linked eggs to cholesterol, but people can consume eggs safely. Learn about eating…. An appetite suppressant is a particular food, supplement, or lifestyle choice that reduces feelings of hunger. Some methods are more effective than…. Fiber is an essential nutrient for boosting heart and gut health, and yet hardly anyone includes enough of it in their daily diet. In this article, we…. The humble potato has dropped in popularity recently as people switch to low-carb diets. But potatoes are a rich source of vitamins, minerals, and…. Recent research suggests that following the Atlantic diet, which is similar to the Mediterranean diet, may help prevent metabolic syndrome and other…. My podcast changed me Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health? Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut Tools General Health Drugs A-Z Health Hubs Health Tools Find a Doctor BMI Calculators and Charts Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide Sleep Calculator Quizzes RA Myths vs Facts Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction Connect About Medical News Today Who We Are Our Editorial Process Content Integrity Conscious Language Newsletters Sign Up Follow Us. Medical News Today. Health Conditions Health Products Discover Tools Connect. What are the most filling foods? Medically reviewed by Katherine Marengo LDN, R. Boiled or baked potato Pulses High-fiber foods Low-fat dairy products Eggs Nuts Lean meat and fish Summary Some foods can maintain the feeling of fullness for longer than others. Boiled or baked potato. Share on Pinterest Potatoes are a dense food that are rich in healthful nutrients. High-fiber foods. Low-fat dairy products. Share on Pinterest Nuts are effective at increasing satiety. Lean meat and fish. How we reviewed this article: Sources. |

| Healthy Satiety | TrainingPeaks | Inflammatory status can be counteracted by modifying diet patterns, including moderate physical activity 23 — Several biomarkers engage in the complex process of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein, considered to reflect inflammatory reactions in atherosclerotic vessels, as well as circulating cytokines and necrosis in acute myocardial infarction Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 PAI-1 , a physiological inhibitor of plasminogen, acts as a biomarker of a pro-thrombotic state. MedDiet interventions have been reported to ameliorate pro-thrombotic status decreasing PAI-1 serum levels 27 , Smoking, alcohol consumption, and age are positively correlated with PAI-1 levels White adipose tissue has been broadly accepted as a metabolic active organ. However, some of its peptides are unclear, for instance, resistin, an antagonist polypeptide of insulin action that may play a role in obesity Controversial results have been obtained regarding the identification of changes in its levels in both obesity and diabetes mellitus 31 , Regarding visfatin, an adipokine with arguably insulin-mimetic effects 33 and which is highly expressed in visceral fat 34 , 35 appears to be upregulated in patients with obesity 36 and type 2 diabetes mellitus Results, however, are inconsistent with respect to insulin sensitivity, waist circumference, body mass index BMI , and HbA1c 38 — In addition, we will establish the association of these markers with weight loss irrespective of the intervention group. The PREDIMED-PLUS is a multicenter lifestyle intervention with 6, eligible participants. It is a 6-year randomized trial conducted in 23 Spanish centers with a large cohort presenting metabolic syndrome recruited from primary healthcare centers. Patients were randomly allocated either to the intervention group or control Those in the former followed an energy-reduced MedDiet with physical activity promotion and behavioral support so as to meet specific weight loss objectives. The participants received recommendations based on a item energy-restricted score. Participants in the control group received educational sessions on an ad libitum MedDiet based on a item non-energy-restricted score. No specific advice for increasing physical activity or losing weight was provided. Regarding the individual sessions, participants in both groups received periodical group sessions and telephone calls once a month in the intensive intervention group and two times a year in the control one. Adherence to diet was assessed with a previously validated item questionnaire employed in the PREDIMED Study for the control group 43 , 44 , which was adapted to the item energy-restricted diet questionnaire for the intervention group. Physical activity practice was evaluated at the beginning of the study and during follow-up. Participants reported activities through the Regicor Short Physical Activity Questionnaire, a validated version adapted from the Minnesota leisure time physical activity questionnaire 46 , Hormone and inflammation-related determinations were performed in a subsample of patients at baseline, with measurements at 6-and month follow-ups of and subjects, respectively. The sample size of glycosylated A1c hemoglobin HbA1c was made up of , , and individuals at the three visits, respectively. Due to sample availability, high sensitivity C-reactive protein hs-CRP was analyzed in individuals. Sample collection was performed after an overnight fasting period at baseline, 6-months, and months of follow-up. Venous blood samples were collected in vacuum tubes with a silica clot activator and K 2 -EDTA anticoagulant Becton Dickinson, Plymouth, United Kingdom to yield serum and plasma, respectively. Serum tubes were centrifuged after the completion of the coagulation process, and plasma tubes immediately after collection, both for 15 min at 1. With the exception of HbA1c which was analyzed with K 2 -EDTA anticoagulated whole blood, the following analytes were quantified in serum with an ABX Pentra auto-analyzer Horiba-ABX, Montpellier, France : glucose, HbA1c, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein HDL cholesterol, and total cholesterol. Remnant-C was estimated as total cholesterol minus LDL cholesterol minus HDL cholesterol. Finally, leptin, ghrelin, glucagon-like peptide-1 GLP-1 , C-peptide, glucagon, insulin, PAI-1, resistin, and visfatin were simultaneously analyzed in plasma by Bio-Plex Pro methodology, a bead-based multiplexing technology with specific capture antibodies coupled with magnetic beads to discriminate analytes using an XMAG-Luminex assay Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA. The fluorescence signal was read on a Bio-Plex equipment Bio-Rad After several washes to remove unbound protein, a biotinylated detection antibody conjugated with fluorescent dye reporter. The inter-assay coefficients of variation CVs of these determinations were between 4. Values under the methodological limit of detection were reported with the limit of detection itself. Leptin measurements from six individuals were removed from the database due to analytical sampling error, and two hs-CRP values were considered outliers. The assessment of the normality distribution of the variables was performed based on normality probability plots and boxplots. Continuous variables were normally shaped, except for triglycerides which were normalized by Napierian logarithm, and median and interquartile ranges were displayed. Lifestyle categorical variables were compared between groups with the Chi-square test. A descriptive statistic table stratified by intervention and control group was summarized including mean values or median if non-normally shaped , and mean differences between 6-and month intervals. In addition, multivariate linear regression models adjusted for sex, age, energy intake baseline value, and baseline value of the variable under study were fitted. To identify possible statistical differences across time, we performed the paired t -test among baseline, 6 months, and 12 months in each group Mann—Whitney U test was carried out for non-normal variables. Weight loss and waist circumference changes were stratified according to the tertiles of the population at the different time points baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. To estimate the extent of variation among the first, second, and third tertiles, the analysis of variance was calculated by adjusting for baseline value and baseline weight. Major weight and waist circumference losses corresponded to the first tertile. The linear mixed-effect models were constructed considering potential significant covariates with age, sex, time, weight, and adherence to MedDiet as fixed effects. Given that time affects individuals differently, it was contemplated as a varying covariate and a random slope constructed. The model contains both linear and quadratic time components so as to determine which trend better fits the model. We also included possible interaction between sex and weight, using the latter to correct the model in all variables except for weight itself. Linear mixed-effect estimation was carried out with the use of restricted maximum likelihood. Accepting an alpha risk of 0. Our study population was a sample of women participants from the IMIM Hospital del Mar Research Institute site within the framework of the PREDIMED PLUS Study. The mean age was Diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and smoking conditions were equally distributed between the two groups without significant differences. The main food items and nutritional parameters are shown in Table 2. In comparison to the control group, the adjusted multivariate of MedDiet adherence, physical activity, weight, waist circumference, remnant cholesterol, triglyceride levels, and HDL cholesterol showed an improvement at 6-month follow-up which was maintained at 12 months. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure presented significant improvements at 6-month follow-up but did not reach significance at 12 months. Regarding carbohydrate metabolism, we found differences between the two groups at 6-and month follow-ups in HOMA, insulin, and C-peptide. Borderline inter-group P -value these explanations were aimed to clarify the meaning of borderline to reviewer 2. Changes in leptin and PAI-1 levels were reported at 12 months, with a 6-month P -value close to significance in the case of PAI Table 1. Baseline and 6-and month changes mean and standard deviation stratified in the control and intervention groups of the participants on the item questionnaire, physical activity, biomarkers, and anthropometric measurements, lipid profile, carbohydrate metabolism, and hormones. Adjusted for sex and age. Table 2. Baseline and differences at 6-and month follow-ups mean and standard deviation stratified in the control and intervention groups in the consumption of key food items and dietary parameters between the control and intensive group adjusted for the baseline value. As expected, the weight loss tertiles showed improvements at mid-and long-term follow-up for MedDiet adherence and physical activity practice regardless of the group. In addition, changes in leptin, PAI-1, and visfatin levels were observed at 6-and month follow-ups Table 3. Waist circumference change tertiles showed similar results to body weight tertiles Table 4. Table 3. Tertiles of weight loss change mean, standard deviation, and their comparison adjusted for weight and baseline value of the participants on the item questionnaire, physical activity, biomarkers and anthropometric measurements, lipid profile, carbohydrate metabolism, and hormones. Table 4. Tertiles of waist circumference change mean, standard deviation, and their comparison adjusted for weight and baseline value of the participants on the item questionnaire, physical activity, biomarkers and anthropometric measurements, lipid profile, carbohydrate metabolism, and hormones. Changes were graphically examined through linear mixed-effect models of cardiovascular risk factors at 6-and month follow-ups to observe the behavior of the repeated measures in both groups. Weight change with moderate positive correlation was reported Supplementary Figure 3. The intervention with an energy-reduced MedDiet and physical activity, versus a non-reduced one, was associated with an improvement in weight, waist circumference, glucose metabolism, triglyceride-related lipid profile, satiety-related hormones leptin , and pro-inflammatory markers PAI-1 at mid-and long-term in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Such changes being maintained over time have been previously reported. Moreover, it has been hypothesized that MedDiet pattern interventions lead to greater compliance and adherence rates, in fact, the number of dropouts registered in trials has been reported to be larger in the control groups 7 , 49 — The MedDiet fat component is of vegetable origin olive oil and nuts and includes an abundance of plant foods vegetables, fruit, whole grains, and legumes , limited fish consumption, and red wine in moderation usually during meals. The intake of red and processed meats, refined grains, potatoes, dairy products, and ultra-processed foods ice cream, sweets, creamy desserts, industrial confectionery, and sugar-sweetened beverages 41 , The hypothesis that the MedDiet is an eating pattern that can be maintained in mid-and long-term with a high degree of acceptance has been reflected in several studies introducing behavioral and nutritional patterns into small population groups 52 , 54 , During other interventions, several participants reported freshness and palatability of food, with variance across the studies regarding taste 56 — Meal plans resulted in hedonic appreciation and satisfaction by most participants 58 , although this differed according to age and dishes In addition to diet acceptability, various limitations have been reported such as the perception of expense, expectation of time commitment, perceived impact on body weight, and cultural differences 56 , 58 — Among a group of schoolchildren, a study found that food neophobia correlated negatively with certain healthy dietary habits, such as fruit and vegetable consumption. The intervention group was based on a hypocaloric diet with moderate fat consumption of vegetable origin: olive oil, tree nuts, and peanuts. Furthermore, it was designed to augment complex carbohydrates and fiber-rich products. Moderate intake of monounsaturated fat in the form of olive oil is one of the cornerstones of MedDiet due to its culinary versatility. Its beneficial effects on the reduction of cardiovascular disease include cardioprotective characteristics, improvement in lipid profile decrease in total and LDL cholesterol and an increase of HDL cholesterol and blood pressure decrease, amelioration of LDL cholesterol oxidation and low-chronic inflammation, and anti-atherogenic properties 61 — While short-term changes are relatively easy to accomplish, successfully maintaining them over time is considerably more difficult. The combination of diet-induced weight loss with exercise training has demonstrated greater improvement in cardiovascular risk factors than diet alone 68 , Our findings from the intervention group showed a decrease in waist circumference and weight at both 6-and month follow-ups, and the comparison with the control was significant for both periods. In the intervention group, the maximum weight loss was at 1 year. Such a finding is particularly relevant since in most studies on the effects of restrictive diets this occurs at 6 months followed by a reward effect. Interventions with hypocaloric diets which can be sustainable over time could, therefore, provide a better approach to weight loss. In this regard, a MedDiet is appropriate as its better palatability, due to its mainly vegetal content and use of olive oil leads to greater adherence. Hyperleptinemia is a characteristic manifestation of obesity in humans. Resistance to leptin action in obesity has been suggested, and elevated circulating concentrations may be necessary to maintain sensitivity to hormone and energy homeostasis 70 , Leptin, as a polypeptide secreted by adipocytes, might be decreased as a result of fat mass reduction 72 , We observed a significant reduction in its levels after both the intervention and control groups. The former displayed an overall stronger decrease probably caused by the further reduction of anthropometric measurements. In fact, a significant reduction was reported comparing the intervention arm to the control at month follow-up. This adipogenic hormone seems to indicate downregulation in human obesity, supposedly as an adaptive mechanism in response to positive energy balance 74 , Diet-induced effects usually show an increase in circulating levels, although reversion to baseline levels at 12 months after a 6-month peak has been reported Our cohort reflected an initial reduction followed by a minor increase in circulating levels in the intensive group, with no statistical significance. Weight loss interventions lead to changes in carbohydrate homeostasis, and increased insulin sensitivity has been observed following dietary interventions, physical activity, and bariatric surgery 77 , Nevertheless, in contrast to isolated interventions, the combined effects of a restricted diet and physical exercise have been reported to improve to a greater extent such sensitivity and variables related to the cardiometabolic syndrome. In our intervention group, insulin levels decreased during the first 6 months and were maintained up to the month follow-up. The control group also experienced a steady reduction although it presented higher levels at 6-and month follow-ups. HOMA, C-peptide, HbA1c, and glucose levels followed a similar pattern. Glucagon improvement caused by diet and exercise training has been reported in the literature. A meta-analysis made up of 29 interventions assessed body weight change, glucagon, insulin, and glucose fasting concentrations after two different weight reduction methods bariatric surgery versus low-caloric diet intervention. The mean decrease in fasting glucagon, however, was not significantly different between both weight reduction approaches Although no inter-group differences in the present study were obtained, a linear time component proved to be a predictor of weight loss regardless of the intervention. Triglyceride reduction is crucial in the management of dyslipidemia, particularly atherogenic dyslipidemia which is highly prevalent in metabolic syndrome subjects. Atherogenic dyslipidemia is characterized by high circulating triglyceride levels and low levels of HDL cholesterol, and even optimal concentrations of LDL cholesterol. Triglyceride concentration is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and is strongly associated with subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue. In fact, it has been suggested that triglycerides could be a predictor of cardiovascular disease The MedDiet has been previously studied as a dietary tool to improve metabolic syndrome and subsequent events 6 , 79 , In this respect, our results show an overall triglyceride reduction in both groups, with a greater reduction in the intervention group than in the control. In concordance, we have recently reported that an energy-reduced MedDiet plus physical activity improves HDL-related triglyceride metabolism versus a non-reduced MedDiet without physical activity Regarding remnant cholesterol, its levels follow a similar pattern to that of triglycerides. Although we did not observe changes after the intervention in total cholesterol, remnant cholesterol decreased in mid-and long-term versus the control group. Such a finding could be a good indicator that the intensive intervention shifted toward protection against cardiovascular risk. High-density lipoprotein HDL cholesterol lipoproteins are known for their atheroprotective effects through a number of anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, anti-thrombotic, and anti-apoptotic properties 83 , An inverse association between triglycerides and HDL cholesterol concentrations usually occurs. In fact, HDL lipoproteins are catabolized faster in the presence of hypertriglyceridemia in non-pathological states. In our study, while the intervention group experienced an increase in the first 6 months and kept a steady concentration at 12 months, the control group had increased HDL cholesterol in the first 6 months which was slightly decreased at 12 months. High sensitivity C reactive protein hs-CRP is broadly used to monitor inflammatory processes, including autoimmune, infectious, tumoral, and metabolic diseases. Prospective epidemiological studies have reported elevated hs-CRP as an independent factor associated with cardiovascular events 26 , Dietary interventions usually lead to inflammatory profile improvement 86 , we observed a reduction in hs-CRP levels across time in both groups, with no significant inter-group results. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 plasma levels are positively associated with cardiovascular disease, thrombosis, fibrosis, and the progression of coronary syndromes They are also positively correlated with individual risk factors BMI, triglycerides, glucose, and mean arterial pressure which may be indicative of their relevance in metabolic syndrome events Diet composition has been demonstrated to affect circulating levels of PAI-1 and the fibrinolytic system as much as alcohol intake and smoking. High-fat diet consumption increases PAI-1 levels impairing clot lysis 29 , In our study, both groups produced a marked change in PAI-1 levels, although decreases were higher in the intensive group, mainly at the month follow-up. Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that, compared to lean individuals, those with obesity have higher resistin levels 90 — Some weight loss programs, however, have not always resulted in a decrease in circulating levels 31 , 93 , 94 , while others reflect parallel reduction 95 , Regarding visfatin, weight loss programs have achieved a decrease in their levels, with no significant difference between them 94 , Nevertheless, there is evidence that a MedDiet has not always demonstrated an improvement in visfatin concentrations In our study, resistin and visfatin levels displayed parallel behavior in both groups with an initial reduction at 6 months followed by steady maintenance at 12 months. Our large sample size and randomized design provide high-quality evidence that minimizes confounding and bias influences. We have comprehensively assessed diverse cardiovascular risk biomarkers and satiety-related hormones. There are, however, some limitations. Second, we observed only moderate differences between the two intervention arms. Such a finding was to be expected as the control group was an active comparator following a healthy traditional MedDiet. Moreover, due to the physiological regulation of ghrelin, among other hormones, the measurement of post-prandial levels would have been inestimable contribution, further research is warranted. Given that such changes were maintained over time, and the marked palatability and acceptability of the MedDiet on the part of the consumers, MedDiet pattern interventions with hypocaloric diets could be a pertinent approach to weight loss. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committees of all centers approved the study protocol during and The trial was registered in at www. MF, JS-S, MM-G, DC, ER, FT, and RE designed the clinical trial. OC and MF designed the conceptualization sub-study. JH-R performed the formal and laboratory analysis. AT and JH-R carried out the statistical analysis. OC, MF, and JH-R drafted the manuscript. AT, DB, JS-S, MM-G, DC, RE, AG, OC, and MF revised and approved the final version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. The funders played no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, and neither in the process of writing the manuscript and its publication. Program in Food Science and Nutrition, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain with file number: JS-S partially supported by the ICREA under the ICREA Academia programme. We thank Daniel Muñoz-Aguayo, Gemma Blanchart, and Sònia Gaixas for their laboratory support, and Stephanie Lonsdale for her help in editing the English text. We also thank all PREDIMED and PREDIMED-Plus study collaborators, PREDIMED-Plus Biobank Network as a part of the National Biobank Platform of the ISCIII for storing and managing the PREDIMED-Plus biological samples. CIBER de Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición CIBERobn is an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III Madrid, Spain , and is financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. MedDiet, Mediterranean diet; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs-CRP, highly sensitivity C-reactive protein; K2-EDTA, dipotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; CV, coefficient of variation. Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després JP, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Google Scholar. Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, Howard BV, Lefevre M, Lustig RH, et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Zorena K, Jachimowicz-Duda O, Ślęzak D, Robakowska M, Mrugacz M. Adipokines and obesity. Potential link to metabolic disorders and chronic complications. Int J Mol Sci. Papadaki A, Nolen-Doerr E, Mantzoros CS. The effect of the Mediterranean diet on metabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials in adults. Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas MI, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. Kastorini CM, Milionis HJ, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Goudevenos JA, Panagiotakos DB. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: a meta-analysis of 50 studies and , individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. Freitas Lima LC, de Braga AV, do Socorro de França Silva M, de Cruz CJ, Sousa Santos SH, de Oliveira Monteiro MM, et al. Adipokines, diabetes and atherosclerosis: an inflammatory association. Front Physiol. Morton GJ, Meek TH, Schwartz MW. Neurobiology of food intake in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Daniel Porte JR, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Hayes MR, Miller CK, Ulbrecht JS, Mauger JL, Parker-Klees L, Davis Gutschall M, et al. A carbohydrate-restricted diet alters gut peptides and adiposity signals in men and women with metabolic syndrome. J Nutr. Rashad NM, Sayed SE, Sherif MH, Sitohy MZ. Effect of a week weight management program on serum leptin level in correlation to anthropometric measures in obese female: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr. Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. Salas-Salvadó J, Díaz-López A, Ruiz-Canela M, Basora J, Fitó M, Corella D, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention program with energy-restricted Mediterranean diet and exercise on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: one-year results of the PREDIMED-plus trial. Diabetes Care. Wren A, Bloom S. Gut hormones and appetite control. Yanagi S, Sato T, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Review the homeostatic force of ghrelin. Cell Metab. Gepner Y, Shelef I, Schwarzfuchs D, Zelicha H, Tene L, Meir AY, et al. Effect of distinct lifestyle interventions on mobilization of fat storage pools CENTRAL magnetic resonance imaging randomized controlled trial. Sánchez-Margalet V, Sánchez-Margalet V, Martín-Romero C, Santos-Alvarez J, Goberna R, Najib S, et al. Role of leptin as an immunomodulator of blood mononuclear cells: mechanisms of action. Clin Exp Immunol. Dixit VD, Schaffer EM, Pyle RS, Collins GD, Sakthivel SK, Palaniappan R, et al. Ghrelin inhibits leptin-and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. J Clin Invest. Loffreda S, Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Karp CL, Brengman ML, Wang DJ, et al. Leptin regulates proinflammatory immune responses. FASEB J. Chen K, Li F, Li J, Cai H, Strom S, Bisello A, et al. Induction of leptin resistance through direct interaction of C-reactive protein with leptin. Nat Med. de Rosa S, Cirillo P, Pacileo M, di Palma V, Paglia A, Chiariello M. Leptin stimulated C-reactive protein production by human coronary artery endothelial cells. J Vasc Res. Salas-Salvadó J, Garcia-Arellano A, Estruch R, Marquez-Sandoval F, Corella D, Fiol M, et al. Components of the mediterranean-type food pattern and serum inflammatory markers among patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Nutr. Chrysohoou C, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Das UN, Stefanadis C. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet attenuates inflammation and coagulation process in healthy adults: the ATTICA study. The initial research on the biology of satiety was conducted at Columbia and Cornell Universities almost 40 years ago. Additional studies have shown how CCK is released and how it works. Although many large drug companies have intense research efforts to develop drugs that stimulate the feel-full proteins, some of the latest research shows that consuming the right types of nutrients at the right time is also effective. These discoveries open up enormous possibilities in terms of helping people lose weight and maintain a healthy weight. There are two primary dietary practices that promote healthy satiety. With the increased prevalence of energy-dense processed foods, the availability of eat-and-go restaurants, and busy lifestyles, most Americans consume meals in a very short period of time. A meal at a fast food restaurant, which can be as much as 1, calories, can be consumed in five minutes. Healthy satiety involves changing your meal pattern to turn on your appetite control mechanisms before you eat your meal. The best way to do this is to consume foods that contain those nutrients which are extremely effective in activating the feel-full proteins. The fats that are most effective are called long-chain fatty acids. These are also monounsaturated fats and are found in high concentrations in corn oil, canola oil, olive oil, safflower oil, sunflower oil, peanut oil and soybean oil. Although not as potent has the aforementioned fats, certain proteins, especially soy and whey a dairy protein , are very effective. Consuming a small amount of foods rich in these nutrients will release the feel full proteins before you start eating. Thus, you will feel fuller even if you eat fewer calories. Here are some high satiety appetizers. Because these oils are so effective in turning off your appetite, you only need a small amount. The ideal type of meal to eat for healthy satiety provides maximum satisfaction without too many calories. A healthy, Satisfilling meal has three components: at least one low-density food, at least one high-satiety food, and a satiety activator. The least energy-dense foods are those that contain a lot of fiber, which is found prevalently in fruits and vegetables. Such foods help us eat less because they fill a lot of space in the stomach with relatively few calories. If we combine these foods with those that also have high satiating value we get the best of both worlds — fullness and satiety — with fewer calories. The table below lists examples of low-density foods that provide fullness and high-satiety foods that offer satiety. Healthy Satisfilling meals should not include processed foods that contain high amounts of saturated fats and sugars, which give you calories without providing meal satisfaction fullness plus satiety. In addition to the two primary steps to healthy satiety, there are three secondary steps. The more frequently you eat throughout the day, the less hunger and the more satiety you will experience between meals. When you are less hungry at the start of each meal, you will tend to eat less. When you skip breakfast, you are usually extremely hungry later in the day, and consequently eat much more. Eating breakfast results in a feeling of satiety that causes you to eat less during the rest of the day. A study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that women who ate breakfast voluntarily consumed roughly fewer calories throughout the entire day than women who skipped breakfast. There are three essential requirements for successful weight loss: calorie reduction, exercise, and healthy satiety. The slight reduction in daily calorie intake that is needed for weight loss can be achieved on a variety of diets: low-fat diet, low-glycemic, Mediterranean, and so forth. |

| Introduction | Changss differentiation in the lubricity of hydrogels was used for Satiety promoting lifestyle changes first chsnges by Krop et Promotng. Systolic and diastolic blood Workout plans for women presented significant improvements at 6-month follow-up but did not reach Satiety promoting lifestyle changes at 12 months. Patients were randomly allocated either to the intervention group or control By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. It is noteworthy that some of the authors relate their findings of increased satiety after consuming high viscous foods to a slower gastric emptying rate, which should be interpreted with some caution. Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. |

| Food and Diet | Statistical analysis The assessment of the normality distribution of the Causes of obesity was Satieyy based on normality probability plots and Satiety promoting lifestyle changes. Int J Obes Satiwty. Leptin regulates proinflammatory immune responses. Satiety promoting lifestyle changes as an endocrine organ, it Satiety promoting lifestyle changes lifestyoe receives information through promotinng complex network of cytokines, hormones, and substrates contributing to a low-chronic inflammation environment. However, no effect of food form on fullness was observed. Adherence to diet was assessed with a previously validated item questionnaire employed in the PREDIMED Study for the control group 4344which was adapted to the item energy-restricted diet questionnaire for the intervention group. Interventions with hypocaloric diets which can be sustainable over time could, therefore, provide a better approach to weight loss. |

Nach meiner Meinung lassen Sie den Fehler zu. Ich biete es an, zu besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM.

Ich denke, dass Sie den Fehler zulassen. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden besprechen.

Hier kann der Fehler nicht sein?

Mir scheint es, dass es schon besprochen wurde, nutzen Sie die Suche nach dem Forum aus.