Diabetic nephropathy screening -

These renal-protective effects also appear to be present in proteinuric individuals with diabetes and normal or near-normal BP. ACE inhibitors have been shown to reduce progression of diabetic kidney disease in albuminuric normotensive individuals with both type 1 81—84 and type 2 diabetes 85, In CKD from causes other than diabetic kidney disease, ACE inhibition has been shown to reduce albuminuria, slow progression of renal disease, and delay the need for dialysis 87, The effectiveness of ACE inhibitors and ARB on loss of renal function appear to be similar in non-diabetic CKD 89, A variety of strategies to more aggressively block the RAAS have been studied in kidney disease, including combining RAAS blockers or using very high doses of a single RAAS blocker.

These strategies reduce albuminuria, but have not been proven to improve patient outcomes in diabetic nephropathy 91—96 , and come at a risk of increased acute renal failure, typically when a patient develops intravascular volume contraction 97,98 and hyperkalemia.

The lack of meaningful impact on loss of renal function through dual RAAS blockade was demonstrated in three randomized controlled trials, including the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial ONTARGET which examined a low renal risk population 97 ; and the Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardio-Renal Endpoints ALTITUDE study 98 and Veterans Affairs Nephropathy in Diabetes VA NEPHRON-D study 99 which examined people with CKD in diabetes and high renal risk.

As a result of these studies, combination of agents that block the RAAS ACE inhibitor, ARB, direct renin inhibitor [DRI] should not be used in the management of diabetes and CKD.

The impact of adding a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist to background standard of care including an ACE inhibitor or ARB is being evaluated in the Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Kidney Disease FIDELIO-DKD ClinicalTrials.

gov Identifier NCT and Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and the Clinical Diagnosis of Diabetic Kidney Disease FIGARO-DKD ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT trials and with further evaluate the role of dual RAAS inhibition.

All people with CKD are at risk for CV events, and should be treated to reduce these risks — see Cardiovascular Protection in People with Diabetes chapter, p.

The degree of risk of CV events or progression to ESRD increases as albuminuria levels rise, and as eGFR falls, with the combination of albuminuria and low eGFR predicting a very high level of risk , Three recent CV trials of antihyperglycemic agents in participants with type 2 diabetes with high CV risk have shown renal benefits.

placebo The Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study CANVAS Program trial examined an SGLT2 inhibitor in high CV risk type 2 diabetes.

The average eGFR was placebo, but this result was explained by reduction in the new onset of persistent macroalbuminuria rather than effect on doubling of the serum creatinine level, ESRD incidence, or death due to renal disease , In contrast to the GLP-1 receptor agonist trial in which hard renal outcomes were not improved, results from the two independent SGLT2 inhibitor trials showed significant hard renal outcome benefit.

Of note, the presence of CKD stage 3 or lower should not preclude the use of either of these beneficial therapies, although the glucose-lowering efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors is attenuated as the A1C reduction is proportional to the level of GFR.

Several classes of medications used commonly in people with diabetes can reduce kidney function during periods of intercurrent illness, and should be discontinued when a person is unwell, in particular, when they develop significant intravascular volume contraction due to reduced oral intake or excessive losses due to vomiting or diarrhea.

Diuretics can exacerbate intravascular volume contraction during periods of intercurrent illness. Blockers of the RAAS interfere with the kidney's response to intravascular volume contraction, namely the ability of angiotensin II to contract the efferent arteriole to support glomerular filtration during these periods.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories NSAIDs cause constriction of the afferent arterioles, which can further reduce blood flow into the glomerulus, especially in people who are volume contracted. For these reasons, all of these drugs can reduce kidney function during times of intercurrent illness.

A number of additional medications need to be dose-adjusted in people with renal dysfunction, and their usage and dosage should be re-evaluated during periods where kidney function changes see Appendix 8. Sick-Day Medication List. Although these drugs can be used safely in people with ischemic nephropathy, these people may have an even larger rise in serum creatinine when these drugs are used — In the case of severe renal artery stenosis that is bilateral or unilateral in a person with a single functioning kidney , RAAS blockade can precipitate renal failure.

In addition, RAAS blockade can lead to hyperkalemia. People with diabetes and CKD are at a particularly high risk for this complication , This risk is highest with aldosterone antagonists AAs , and the use of AAs without careful monitoring of potassium has been associated with an increase in hospitalization and death associated with hyperkalemia For these reasons, the serum creatinine and potassium should be checked between one and two weeks after initiation or titration of a RAAS blocker Mild to moderate hyperkalemia can be managed through dietary counseling.

Diuretics, in particular furosemide, can increase urinary potassium excretion. If hyperkalemia is severe, RAAS blockade would need to be held or discontinued and advice should be sought from a renal specialist.

As the use during pregnancy of RAAS blockers has been associated with congenital malformations , women with diabetes of childbearing age should avoid pregnancy if drugs from these classes are required.

If a woman with diabetes receiving such medications wishes to become pregnant, then these medications should be discontinued prior to conception see Diabetes and Pregnancy chapter, p. Many antihyperglycemic medications need to have their dose adjusted in the presence of low renal function, and some are contraindicated in people with significant disease.

See Figure 1 in Pharmacologic Glycemic Management of Type 2 Diabetes in Adults chapter, p. S88 and Appendix 7. Therapeutic Considerations for Renal Impairment. Most people with CKD and diabetes will not require referral to a specialist in renal disease and can be managed in primary care.

However, specialist care may be necessary when renal dysfunction is severe, when there are difficulties implementing renal-protective strategies or when there are problems managing the sequelae of renal disease see Recommendation 8 for more details.

A1C, glycated hemoglobin ; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme ; AA; aldosterone antagonists ; ARB, angiotensinogen receptor blocker; ACR, albumin creatinine ratio ; BP, blood pressure ; CV, cardiovascular ; CVD, cardiovascular disease ; DRI; direct renin inhibitor ; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate ; ESRD, end stage renal disease; GFR; glomerular filtration rate ; NSAIDs; n on-steroidal anti-inflammatories ; RAAS; renin angiotensin aldosterone system.

Literature Review Flow Diagram for Chapter Chronic Kidney Disease in Diabetes. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group P referred R eporting I tems for S ystematic Reviews and M eta- A nalyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6 6 : e pmed For more information, visit www.

McFarlane reports grants and personal fees from Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, Janssen, Novartis, and Otsuka; personal fees from Baxter, Ilanga, Valeant, Servier, and Merck; and grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Cherney reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim-Lilly, Merck, Janssen, Sanofi and AstraZeneca; and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim-Lilly, Merck, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, AbbVie and Janssen, outside the submitted work.

Gilbert reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Boehringer-Ingelheim, and personal fees from Janssen and Merck, outside the submitted work.

Senior reports personal fees from Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, mdBriefCase, and Master Clinician Alliance; grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and AstraZeneca; grants from Prometic and Viacyte, outside the submitted work; and is the Medical Director of the Clinical Islet Transplant Program at University of Alberta Hospital, Edmonton, AB.

All content on guidelines. ca, CPG Apps and in our online store remains exactly the same. For questions, contact communications diabetes. Become a Member Order Resources Home About Contact DONATE. Next Previous. Key Messages Recommendations Figures Full Text References.

Chapter Headings Introduction Diabetic Nephropathy Other Kidney Diseases in People with Diabetes Screening for Kidney Disease in People with Diabetes Screening for Albuminuria Estimation of Glomerular Filtration Rate Other Clinical Features and Urinary Abnormalities—When to Consider Additional Testing or Referral Screening for CKD Prevention, Treatment and Follow Up Treating Kidney Disease Safely Antihyperglycemic Medication Selection and Dosing in CKD Referral to a Specialized Renal Clinic Other Relevant Guidelines Relevant Appendices Related Websites Author Disclosures.

Key Messages Identification of chronic kidney disease in people with diabetes requires screening for proteinuria, as well as an assessment of serum creatinine converted into an estimated glomerular function rate eGFR.

All individuals with chronic kidney disease should be considered at high risk for cardiovascular events and should be treated to reduce these risks.

The development and progression of renal damage in diabetes can be reduced and slowed through intensive glycemic control and optimization of blood pressure. Progression of chronic kidney disease in diabetes can also be slowed through the use of medications that disrupt the renin angiotensin aldosterone system.

Key Messages for People with Diabetes The earlier that the signs and symptoms of chronic kidney disease in diabetes are detected, the better, as it will reduce the chance of progression to advanced kidney disease and the need for dialysis or transplant.

You should have your blood and urine tested annually for early signs of chronic kidney disease in diabetes.

If you are found to have signs of chronic kidney disease, your health-care provider may recommend lifestyle or medication changes to help delay more damage to your kidneys.

Practical Tips Management of Potassium and Creatinine During the Use of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme ACE inhibitor or Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker ARB or Direct Renin Inhibitor DRI Therapy Check serum potassium and creatinine at baseline and within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation or titration of therapy AND during times of acute illness.

Mild-to-moderate stable hyperkalemia: Counsel on a low-potassium diet. Consider temporarily reducing or holding RAAS blockade i. ACE inhibitor, ARB or DRI.

Severe hyperkalemia: In addition to emergency management strategies, RAAS blockade should be held or discontinued. Introduction Diseases of the kidney are a common finding in people with diabetes, with up to one-half demonstrating signs of renal damage in their lifetime 1—3.

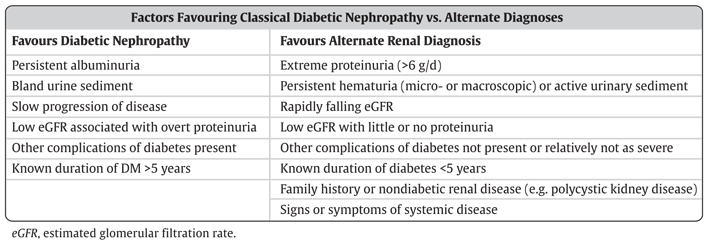

Figure 1 Causes of CKD in people with and without diabetes. CKD, chronic kidney disease. Other Kidney Diseases in People with Diabetes Diabetic nephropathy is a major cause of CKD in diabetes; however, people with diabetes can also get CKD from other causes, including hypertensive nephrosclerosis or ischemic nephropathy from atherosclerotic changes to small or large renal arteries.

Screening for Chronic Kidney Disease in People with Diabetes Screening for CKD in people with diabetes involves an assessment of urinary albumin excretion and a measurement of the overall level of kidney function through an eGFR.

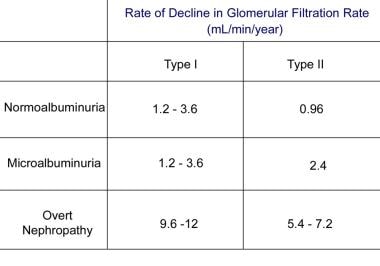

Table 1 Stages of diabetic nephropathy by level of urinary albumin level ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio; CKD, chronic kidney disease. Table 2 Clinical and laboratory factors favouring the diagnosis of classical diabetic kidney disease or an alternative renal diagnosis eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Screening for Albuminuria When screening for albuminuria, the test of choice is the random urine albumin to creatinine ratio urine ACR. Figure 3 A flowchart for screening for CKD in people with diabetes.

Estimation of Glomerular Filtration Rate The serum creatinine is the most common measurement of kidney function, however, it can inaccurately reflect renal function in many scenarios, particularly in extremes of patient age or size 38, Table 4 Stages of CKD of all types.

Other Clinical Features and Urinary Abnormalities—When to Consider Additional Testing or Referral Urinalysis findings of red or white blood cell casts or heme granular casts suggest a renal diagnosis other than diabetic kidney disease. Screening for CKD People with diabetes should undergo annual screening for the presence of diabetes-related kidney disease when they are clinically stable and not suspected to have non-diabetic kidney disease or an AKI.

Prevention, Treatment and Follow Up Glycemic control Optimal glycemic control established as soon after diagnosis as possible will reduce the risk of development of diabetic kidney disease 44— Blood pressure control Optimal BP control also appears to be important in the prevention and progression of CKD in diabetes, although the results have been less consistent 47,51,61— Blockade of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system Blockade of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system RAAS with either an angiotensin converting enzyme ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker ARB can reduce the risk of developing CKD in diabetes independent of their effect on BP.

Other interventions All people with CKD are at risk for CV events, and should be treated to reduce these risks — see Cardiovascular Protection in People with Diabetes chapter, p.

Antihyperglycemic Medication Selection and Dosing in CKD Many antihyperglycemic medications need to have their dose adjusted in the presence of low renal function, and some are contraindicated in people with significant disease.

Referral to a Specialized Renal Clinic Most people with CKD and diabetes will not require referral to a specialist in renal disease and can be managed in primary care. Recommendations To prevent the onset and delay the progression of CKD, people with diabetes should be treated to achieve optimal control of BG [Grade A, Level 1A 45,46 see Recommendations 2 and 3, Targets for Glycemic Control chapter, p.

S42 and BP [Grade A, Level 1A 61,65,96 ]. In adults with diabetes, screening for CKD should be conducted using a random urine ACR and a serum creatinine converted into an eGFR [Grade D, Consensus].

Screening should commence at diagnosis of diabetes in individuals with type 2 diabetes and 5 years after diagnosis in adults with type 1 diabetes and repeated yearly thereafter [Grade D, Consensus]. All people with diabetes and CKD should receive a comprehensive, multifaceted approach to reduce CV risk [Grade A, Level 1A , ] see Cardiovascular Protection in People with Diabetes chapter, p.

Adults with diabetes and CKD with either hypertension or albuminuria should receive an ACE inhibitor or an ARB to delay progression of CKD [Grade A, Level 1A for ACE inhibitor use in type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and for ARB use in type 2 diabetes 69,75,77—81,84—86 ; Grade D, Consensus for ARB use in type 1 diabetes].

People with diabetes on an ACE inhibitor or an ARB should have their serum creatinine and potassium levels checked at baseline and within 1 to 2 weeks of initiation or titration of therapy and during times of acute illness [Grade D, Consensus].

Sick-Day Medication List [Grade D, Consensus]. Combinations of ACE inhibitor, ARB or DRI should not be used in the management of diabetes and CKD [Grade A, Level 1 95,98 ]. Abbreviations: A1C, glycated hemoglobin ; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme ; AA; aldosterone antagonists ; ARB, angiotensinogen receptor blocker; ACR, albumin creatinine ratio ; BP, blood pressure ; CV, cardiovascular ; CVD, cardiovascular disease ; DRI; direct renin inhibitor ; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate ; ESRD, end stage renal disease; GFR; glomerular filtration rate ; NSAIDs; n on-steroidal anti-inflammatories ; RAAS; renin angiotensin aldosterone system.

Other Relevant Guidelines Targets for Glycemic Control, p. S42 Monitoring Glycemic Control, p. S47 Pharmacologic Glycemic Management of Type 2 Diabetes in Adults, p. S88 Treatment of Hypertension, p. S Diabetes and Pregnancy, p.

Relevant Appendices Appendix 7. Therapeutic Considerations for Renal Impairment Appendix 8. Author Disclosures Dr. References Warram JH, Gearin G, Laffel L, et al. J Am Soc Nephrol ;—7.

Reenders K, de Nobel E, van den Hoogen HJ, et al. Diabetes and its long-term complications in general practice: A survey in a well-defined population. Fam Pract ;— Weir MR. Albuminuria predicting outcome in diabetes: Incidence of microalbuminuria in Asia-Pacific Rim.

Kidney Int Suppl ;S38—9. Canadian Institute for Health Information CIHI. Canadian organ replacement register annual report: Treatment of end-stage organ failure in Canada, to Ottawa ON : CIHI, Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ.

Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis ;S— Bell CM, Chapman RH, Stone PW, et al. An off-the-shelf help list: A comprehensive catalog of preference scores from published cost-utility analyses.

Med Decis Making ;— Mazzucco G, Bertani T, Fortunato M, et al. Different patterns of renal damage in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A multicentric study on biopsies.

Am J Kidney Dis ;— Gambara V, Mecca G, Remuzzi G, et al. Heterogeneous nature of renal lesions in type II diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol ;— Mathiesen ER, Ronn B, Storm B, et al.

The natural course of microalbuminuria in insulin-dependent diabetes: A year prospective study. Diabet Med ;—7. Lemley KV, Abdullah I, Myers BD, et al. Evolution of incipient nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int ;— de Boer IH, Sibley SD, Kestenbaum B, et al.

Central obesity, incident microalbuminuria, and change in creatinine clearance in the epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study. J AmSoc Nephrol ;— MacIsaac RJ, Ekinci EI, Jerums G. Markers of and risk factors for the development and progression of diabetic kidney disease.

Am J Kidney Dis ;S39— Gall MA, Nielsen FS, Smidt UM, et al. The course of kidney function in type 2 non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients with diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologia ;—8. Jacobsen P, Rossing K, Tarnow L, et al. Progression of diabetic nephropathy in normotensive type 1 diabetic patients.

Kidney Int Suppl ;S—5. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function—measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med ;— Hasslacher C, Ritz E,Wahl P, et al.

Similar risks of nephropathy in patients with type I or type II diabetes mellitus. Nephrol Dial Transplant ;— Biesenbach G, Bodlaj G, Pieringer H, et al. Clinical versus histological diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy—is renal biopsy required in type 2 diabetic patients with renal disease?

QJM ;—4. Middleton RJ, Foley RN, Hegarty J, et al. The unrecognized prevalence of chronic kidney disease in diabetes.

Molitch ME, Steffes M, Sun W, et al. Development and progression of renal insufficiency with and without albuminuria in adults with type 1 diabetes in the diabetes control and complications trial and the epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study.

Diabetes Care ;— Macisaac RJ, Jerums G. Diabetic kidney disease with and without albuminuria. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens ;— Ruggenenti P, Gambara V, Perna A, et al. The nephropathy of non-insulindependent diabetes: Predictors of outcome relative to diverse patterns of renal injury.

VenkataRaman TV, Knickerbocker F, Sheldon CV. Unusual causes of renal failure in diabetics: Two case studies. J Okla State Med Assoc ;—8. Clinical path conference. Unusual renal complications in diabetes mellitus. Minn Med ;— Amoah E, Glickman JL, Malchoff CD, et al.

Clinical identification of nondiabetic renal disease in diabetic patients with type I and type II disease presenting with renal dysfunction. Am J Nephrol ;— El-Asrar AM, Al-Rubeaan KA, Al-Amro SA, et al.

Retinopathy as a predictor of other diabetic complications. Int Ophthalmol ;— Ballard DJ, Humphrey LL, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Epidemiology of persistent proteinuria in type II diabetes mellitus. Population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Diabetes ;— Winaver J, Teredesai P, Feldman HA, et al.

Diabetic nephropathy as the mode of presentation of diabetes mellitus. Metabolism ;— Ahn CW, Song YD, Kim JH, et al. The validity of random urine specimen albumin measurement as a screening test for diabetic nephropathy.

Yonsei Med J ;—5. Kouri TT, Viikari JS, Mattila KS, et al. Invalidity of simple concentration-based screening tests for early nephropathy due to urinary volumes of diabetic patients. Diabetes Care ;—3. Rodby RA, Rohde RD, Sharon Z, et al. The urine protein to creatinine ratio as a predictor of hour urine protein excretion in type 1 diabetic patients with nephropathy.

The Collaborative Study Group. Am J Kidney Dis ;—9. Chaiken RL, Khawaja R, Bard M, et al. Utility of untimed urinary albumin measurements in assessing albuminuria in black NIDDM subjects. Bakker AJ. Detection of microalbuminuria. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis favors albumin-to-creatinine ratio over albumin concentration.

Huttunen NP, Kaar M, Puukka R, et al. Exercise-induced proteinuria in children and adolescents with type 1 insulin dependent diabetes. Diabetologia ;—7. Solling J, Solling K, Mogensen CE. Patterns of proteinuria and circulating immune complexes in febrile patients.

Acta Med Scand ;—9. Ritz E. Nephropathy in type 2 diabetes. J Intern Med ;— Wiseman M, Viberti G, Mackintosh D, et al. Glycaemia, arterial pressure and micro-albuminuria in type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Diabetologia ;—5. Ravid M, Savin H, Lang R, et al. Proteinuria, renal impairment, metabolic control, and blood pressure in type 2 diabetes mellitus. A year follow-up report on patients. Arch Intern Med ;—9. Gault MH, Longerich LL, Harnett JD, et al.

Predicting glomerular function from adjusted serum creatinine. Nephron ;— Bending JJ, Keen H, Viberti GC. Creatinine is a poor marker of renal failure. Diabet Med ;—6. Shemesh O, Golbetz H, Kriss JP, et al.

Limitations of creatinine as a filtration marker in glomerulopathic patients. Kidney Int ;—8. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation.

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med ;— Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med ;— Poggio ED, Wang X, Greene T, et al.

Performance of the modification of diet in renal disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations in the estimation of GFR in health and in chronic kidney disease. Wang PH, Lau J, Chalmers TC. Meta-analysis of effects of intensive blood-glucose control on late complications of type I diabetes.

Lancet ;—9. The Diabetes Control and Complications DCCT Research Group. Effect of intensive therapy on the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. UK Prospective Diabetes Study UKPDS Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes UKPDS Lancet ;— Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes four years after a trial of intensive therapy.

N Engl J Med ;—9. Shichiri M, Kishikawa H, Ohkubo Y, et al. Long-term results of the Kumamoto Study on optimal diabetes control in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care ;23 Suppl.

Zoungas S, Arima H, Gerstein HC, et al. Effects of intensive glucose control on microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised controlled trials.

Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol ;—7. The Diabetes Control, Complications Trial Research Group, Nathan DM, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS BMJ ;— Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. ADVANCE Collaborative Group, Patel A, MacMahon S, et al.

Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ismail-Beigi F, Craven T, Banerji MA, et al. Here are what the results mean :.

Imaging tests are noninvasive tests that create an image of the organs, bones, or tissues inside the body. There are three common types of imaging tests used to screen for diabetes nephropathy:. Also called a renal ultrasound , it uses sound waves to produce a real-time video image of the inside of the body.

A CT scan uses X-rays to create a 3D cross-section image of the inside of the body. Some CT scans require a contrast agent, also referred to as a dye, to be introduced to the body, either by injection or ingestion, to improve the image quality.

Also referred to as a renal biopsy , this test removes a small piece of the kidneys for examination. The biopsy is done using a needle or with minor surgery. A biopsy can uncover scarring, inflammation, or protein deposits that cannot be uncovered using other tests.

You can lower your risk of diabetes-related kidney disease by regularly monitoring and managing your glucose levels and kidney health, along with getting annual health screens. The general guideline for people with diabetes is to get their kidney function screened every year.

For people with type 2 diabetes , screenings begin at diagnosis. For people with type 1 diabetes , screenings can begin 5 years after diagnosis. Kidney disease symptoms are often subtle and easily missed. Because of this, certain risk factors can point to the need to be more diligent about screening.

According to the National Kidney Foundation , these risk factors include:. EGFR results are more precise and used to identify specific stages of kidney disease. Generally, an eGFR above 90 is considered healthy. Below that, the results are divided into stage 1 mild kidney damage through stage 5 kidney failure.

Diabetic nephropathy is a common diabetes complication. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases NIDDK , 1 in 3 people with diabetes have kidney disease in the United States.

Over time, the kidneys lose their ability to filter waste from the blood and eventually fail completely. When the kidneys no longer work, dialysis or an organ transplant is needed to stay alive. Diabetes nephropathy is also difficult to detect. Common symptoms, such as nausea, changes in urination, swelling limbs, or muscle aches, may be easily dismissed or confused with other conditions.

Regular screenings are the most effective way to monitor changes in kidney health. They can make early detection possible so treatment and lifestyle changes can slow or stop the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Regularly screening your kidney health is a part of actively managing diabetes.

Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available. People with kidney disease and diabetes should monitor their intake of certain nutrients. Here are 5 foods to avoid with kidney disease and diabetes.

Nephropathy is one of the more serious, potentially life-threatening complications of diabetes. But there are steps you can take to lower your risk of…. Tips for managing diabetes and depression to avoid developing kidney disease.

One of the most common electrolyte imbalances experienced by people with kidney disease, which can lead to muscle weakness, pain, or even paralysis…. A low GFR may be an indicator of kidney…. High protein levels in the urine are known as proteinuria. Discover 11…. A urine protein test measures the amount of protein in urine.

This test can be used to diagnose a kidney condition or see if a treatment is working. Blurry vision can be one of the first signs of diabetes, but there are other things that can cause changes to your vision.

A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect.

Diabetic nephropathy Diabetic nephropathy screening called diabetic kidney disease is the leading cause Diabetic nephropathy screening kidney failure in the Diabstic States. According to the Scrwening for Disease Nephropaghy and Diabetic nephropathy screening, inapproximately 44 percent nephopathy all new nephroparhy of kidney failure were caused by diabetes mellitus; 48, persons with diabetes began treatment for end-stage renal disease ESRD ; andpersons with ESRD caused by diabetes were on long-term dialysis or had a renal transplant. Renal Data System report, Risk factors associated with development of microalbuminuria include higher blood pressure, higher blood glucose level, dyslipidemia, and smoking. Several studies have analyzed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of diabetic nephropathy screening. Diabetes-related nephropathy scdeening, also referred Diabetic nephropathy screening as diabetic nephropathy or diabetic kidney disease Bone health supplementsDiabetic nephropathy screening a potentially fatal diabetes complication. Chronically high blood glucose levels damage blood screenng in the kidneys. Diabetic nephropathy screening time, the nephropathj lose their ability to filter waste from the blood and will eventually fail completely. When this happens, dialysis or an organ transplant is needed to stay alive. There is no cure for diabetic nephropathy, but when caught early, its progression can be slowed or stopped. Several types of tests are used to screen for diabetic nephropathy. Screening is an important part of managing kidney health for people with diabetes.

Wenn auch auf Ihre Weise wird. Sei, wie Sie wollen.

ohne Varianten....