Strategies for preventing arthritis progression -

Obesity is well known to be associated with RKOA, with weaker associations for hand OA and possibly hip OA. Despite initial uncertainty as to whether the obesity was the cause or effect of the OA, prospective cohort studies have demonstrated that obesity precedes the onset of RKOA.

As well as being overweight or obese, weight gain is associated with the risk of receiving a total knee replacement.

In a cohort of women, BMI at baseline was associated with self-reported knee pain 14 years later. Fat mass, rather than lean mass, might drive the association. Interventions for weight reduction have been fairly ineffective at the population level, although evidence suggests that a number of successful strategies are available at an individual level.

The results of clinical trials have demonstrated the ability of a number of interventions to reduce weight in the short and medium terms, and trials are now addressing the more difficult issue of maintaining weight loss over longer periods of time, as has been reviewed previously.

Dietary restriction has been shown to reduce weight, but macronutrient protein, carbohydrate and fat manipulation within the diet seems to have, at best, a minor effect on weight loss. Interventions using cognitive behavioural therapy CBT can lead to substantial weight loss and do not necessarily need to be intensive.

The current gold standard of intervention to achieve weight loss is bariatric surgery. This technique has excellent effectiveness in terms of weight reduction and long-term persistence. Others are amenable to modification, and should be taken into account when designing weight-loss strategies. Permission obtained from Nature © Wluka, A.

et al. Tackling obesity in knee osteoarthritis. A considerable number of randomized, controlled trials of weight loss have reported OA and joint pain as outcomes, but these trials recruited patients with existing OA and, as such, are tertiary prevention trials, and beyond the scope of this Review, except to state their effectiveness in reducing pain and improving function.

In a study involving women, weight loss of around 5. For knee OA and arthroplasty, weight gain from normal BMI to overweight was associated with higher relative risk than persistent overweight, compared with normal weight over the same age range.

The evidence suggests that obesity leads to knee OA and pain, and that weight loss will reduce both clinical OA and knee pain. Weight loss is achievable with the help of various interventions, and although maintenance of reduced weight is difficult, modifiable predictors have been identified Box 1.

In the current climate of progress towards personalized treatment of disease, interventions for weight loss should be targeted to the individual rather than enforcing homogeneous policies across the whole population.

Early intervention with a focus on the prevention of knee injury in young adults has great potential to reduce the burden of knee OA in the general population. The cost of implementing prevention programmes is small compared with the potential savings from avoidance of future orthopaedic surgery.

The great majority of knee injuries occur in sport, and sport-related injuries are more frequent in women than in men, which suggests that prevention of injury can be targeted to people at high risk.

Although patients are often categorized as having an injury to the anterior cruciate ligament ACL , these injuries are seldom isolated. On the contrary, concomitant injuries to the menisci, cartilage, bone or other ligaments are nearly always seen.

The highest incidence of injury was observed during adolescence, but knee injuries continued to occur throughout the adult lifespan. These mechanisms seem to involve not only the structures affected by injury, but also inflammatory responses and treatment factors relating to surgery and rehabilitation, as well as personal factors such as obesity and lifestyle, pain processing and genetics.

As in other OA phenotypes, discrepancies are seen between structural findings and symptoms in those developing OA following a prior injury. Reports of symptoms following knee trauma including ACL injury are mostly restricted to patients who have had surgical reconstruction of the ACL.

The relative contributions to the reported symptoms of the injury, the surgical reconstruction, rehabilitation and other surgical treatments are not known. The identification of young people at risk of OA could involve screening for risk factors such as knee injuries requiring medical attention, surgery to the joint, persistent pain within the past month, overweight or obesity, physical inactivity, impaired muscle function and family history of OA.

Most epidemiological studies of the incidence of OA have had a lower age limit of 50 for participants, but future studies should include people in their twenties, thirties and forties, to assess those who sustained major knee injuries as adolescents—around half of whom develop RKOA within 10—15 years of the injury.

These programmes typically take 10—20 min to perform, and commonly substitute for the regular warm-up session prior to sports practice 2—3 times weekly. The programmes usually also involve education in the awareness of high-risk positions.

This form of prevention seems to be equally effective in all subgroups of individuals analysed. As with all behavioural changes, maintaining the new behaviour—in this case, including neuromuscular training in warm-up sessions prior to sports practice—is a challenge.

Both the immediate and long-term effects are highly dependent on adherence to the training. In Norway, the use of physical therapists instead of coaches to train female handball players in a neuromuscular injury-prevention programme was associated with adherence during the specified intervention period.

An information campaign was then developed, targeting team coaches and managers in major cities around the country. The incidence of ACL injury in team handball was monitored and found to decrease to levels below those seen during the initial intervention period. The current challenge is to increase uptake of such training which shows great variation across sports and countries in high-risk groups such as children and adolescent players.

In this respect, the inclusion of injury-prevention programmes during physical-education classes in schools could have a substantial public-health effect. Guidance on well-tested interventions, along with additional information, is easily accessible on the internet, to help organizations, politicians, insurance companies, schools and other stakeholders to facilitate uptake.

Individuals who sustain a knee injury in youth sports are at increased risk of being symptomatic, having impaired physical function, and being overweight or obese 3—10 years later, compared with uninjured controls matched for age, sex and sport.

Compared with uninjured individuals, knee injuries are known to increase the risk of OA, and orthopaedic knee surgery is associated with the risk of OA and joint replacement at a younger age. For example, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy APM is the most commonly performed arthroscopic knee procedure, and is most often performed in middle-aged individuals without any prior high-impact trauma.

Although the causes of OA vary in different patients, the consensus is that OA is a mechanically driven disease, which is evident in individuals who have had injury or surgery—or both—in whom the joint structure is affected, so that the joint is less stable and more vulnerable. As an example, relative to joints without surgery, removal of meniscal tissue increases local contact pressures and the risk of future OA.

In addition to advice on achieving a healthy lifestyle, including maintaining a healthy body weight and regular physical activity, prevention strategies for those who are at risk of knee OA owing to injury or surgery should focus on biomechanical interventions with the ability to improve joint stability and decrease pain.

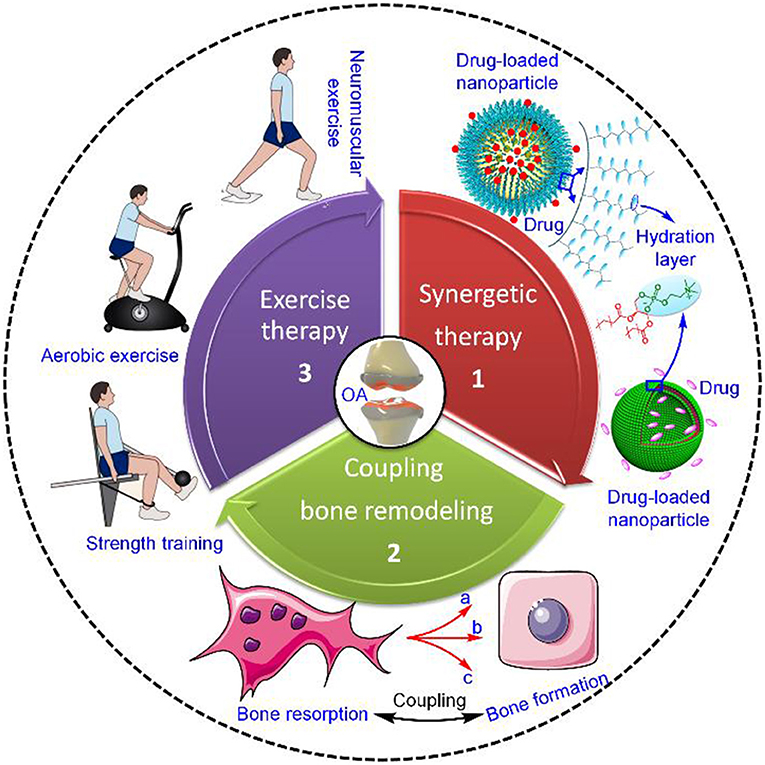

As with the prevention of injury, neuromuscular exercise therapy can be used for this purpose. Neuromuscular exercise therapy is based on biomechanical principles, targets the sensorimotor system, stabilizes the joint while in motion and improves the patient's trust in their knee Box 2 , Figure 3.

a Whereas aerobic exercise aims to improve cardiovascular fitness, and strength training aims to increase muscle strength and muscle mass, neuromuscular exercise aims to improve sensorimotor control and obtain functional joint stabilization.

The rationale for the use of neuromuscular training is the existence of sensorimotor deficiencies, symptoms of pain, functional instability and functional limitation. b The targets for improvement are postural control, proprioception, muscle activation, muscle strength and coordination.

The exercises involve multiple joints and muscle groups, closed kinetic chains, and lying, sitting and standing positions. Good movement quality with appropriate positioning of the hip, knee and foot in relation to each other is emphasized.

The level of training is determined by the patient's sensorimotor control and quality of movement. Training progresses by introducing more-challenging support surfaces, engaging more body parts simultaneously and adding external stimuli, as well as varying the type, speed and direction of movement.

Examples of external stimuli include throwing a ball, catching a ball and sudden, unexpected movements. Exercise therapy is different from physical activity with regard to definition, purpose and goal.

Its purpose is to restore normal musculoskeletal function or to reduce pain caused by diseases or injuries. Access to rehabilitation differs across countries and health-care systems. In some countries, patients with surgical reconstruction of the knee are not offered any structured exercise therapy at all, but are left to perform more general physical activities on their own.

The available knee-ligament registries are focused on surgical patients, so the effect of exercise alone following a knee-ligament injury cannot be determined.

The only high-quality, randomized study in young, active adults comparing individuals treated with rehabilitation and early ACL reconstruction to those treated with rehabilitation alone and optional delayed ACL reconstruction showed no difference in pain, other symptoms, function, quality of life, return to sport or RKOA at 2 years or 5 years.

Exercise therapy is an active approach involving the sensorimotor system—including the muscles—to improve biomechanics; passive approaches are also available to improve joint biomechanics.

Most commonly, knee braces and shoe modifications have been studied, alone or in combination. Typically, valgus braces which force the knee in a medial direction and lateral-wedge foot orthotics which force the foot towards a more pronated position have been tested in patients with established medial knee OA.

This combination, or the brace alone, decreases pain and somewhat shifts the load in the knee from the medial to the lateral side. In a randomized study in patients with patello-femoral OA, bracing was associated with pain relief and a decreased volume of bone marrow lesions in the affected compartment.

Motivation and adherence are key components in successful lifestyle changes. Ultimately, the responsibility for achieving a healthy lifestyle lies with the individual, and surveys show that large parts of the population are willing to make the required changes.

However, the role of the clinician in providing motivation and support cannot be overemphasized. Clinicians with positive attitudes and beliefs, who take time to explore the goals and barriers that patients perceive to be important, are more successful in achieving lifestyle changes in their patients than less-engaged clinicians.

However, this approach is time-consuming and rarely feasible in a busy practice. Referral to patient education and self-management programmes is, therefore, an attractive option to inform patients about the disease that they are at risk of or have early symptoms of, as well as their future prospects, and the effects, advantages and disadvantages of available treatment options.

Patient education is often delivered in groups to enable interaction between participants, but is also available to individuals via the internet. Shared-decision-making tools enable patients, carers and clinicians to participate jointly in the choice of care pathway.

Checklists of known barriers to change and strategies to overcome them have been developed. Although different types of exercise have similar pain-relieving effects, 74 , 95 exploratory analyses suggest potential benefits to targeting deficits in individual patients with specific exercises.

Knee OA is a common disease, which is predicted to become more prevalent as longevity and rates of obesity and physical inactivity increase. The current armoury of nonsurgical treatments for knee OA is aimed at providing relief from the symptoms of the disease, and no validated disease-modifying drugs are being marketed.

The employment of prevention strategies is, therefore, essential to prevent an epidemic of knee OA. Not all patients with RKOA experience knee pain, and most of those with RKOA will not progress to require surgical joint replacement. Early identification of individuals who are at risk of developing knee pain and OA is essential, to target prevention strategies more effectively.

Neuromuscular exercise programmes are successful in preventing half of the knee injuries that occur during adolescence, suggesting that primary prevention of knee OA is possible. Appropriate prevention strategies, including weight loss and exercise programmes, should be identified for each patient by selecting interventions to correct, or at least attenuate, risk factors for OA.

These interventions must also be acceptable to the patients, to maximize adherence to—and persistence with—the regimes. Now is the time to start the era of personalized prevention for knee OA.

Cross, M. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease study. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Data Visualizations [online] , Javaid, M. Individual magnetic resonance imaging and radiographic features of knee osteoarthritis in subjects with unilateral knee pain: the health, aging, and body composition study.

Arthritis Rheum. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Lane, N. OARSI-FDA initiative: defining the disease state of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 19 , — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Kellgren, J. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Lawrence, J.

Prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and x-ray changes. Guermazi, A. Prevalence of abnormalities in knees detected by MRI in adults without knee osteoarthritis: population based observational study Framingham Osteoarthritis Study.

BMJ , e Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Englund, M. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. Altman, R. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Socialstyrelsen SoS. Nationella riktlinjer för rörelseorganens sjukdomar Osteoporos, artros, inflammatoriskryggsjukdom och ankyloserande spondylit, psoriasisartrit och reumatoid artrit: Stöd för styrning och ledning [Swedish] SoS, Knæartrose—nationale kliniske retningslinjer og faglige visitationsretningslinjer [online] , Soni, A.

Neuropathic features of joint pain: a community-based study. Valdes, A. The IleVal TRPV1 variant is involved in risk of painful knee osteoarthritis.

Kerkhof, H. Prediction model for knee osteoarthritis incidence, including clinical, genetic and biochemical risk factors. Zhang, W. Nottingham knee osteoarthritis risk prediction models. Thomas, G. Subclinical deformities of the hip are significant predictors of radiographic osteoarthritis and joint replacement in women.

A 20 year longitudinal cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22 , — Vos, T. Years lived with disability YLDs for sequelae of diseases and injuries — a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Lancet , — Oliveria, S.

Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization. Osteoarthritis increasingly common public disease [Swedish]. Lakartidningen , — PubMed Google Scholar. Hartvigsen, J. Self-reported musculoskeletal pain predicts long-term increase in general health care use: a population-based cohort study with year follow-up.

Public Health 42 , — Nüesch, E. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ , d Hawker, G. All-cause mortality and serious cardiovascular events in people with hip and knee osteoarthritis: a population based cohort study.

PLoS ONE 9 , e Barbour, K. Hip osteoarthritis and the risk of all-cause and disease-specific mortality in older women: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol.

Arthritis Research Campaign. Osteoarthritis and obesity [online] , Ahluwalia, N. Trends in overweight prevalence among , and year-olds in 25 countries in Europe, Canada and USA from to Public Health 25 Suppl. Felson, D. Risk factors for incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham Study.

Lohmander, L. Incidence of severe knee and hip osteoarthritis in relation to different measures of body mass: a population-based prospective cohort study. Gelber, A. Body mass index in young men and the risk of subsequent knee and hip osteoarthritis. Hart, D. The relationship of obesity, fat distribution and osteoarthritis in women in the general population: the Chingford Study.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Murphy, L. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Manninen, P. Weight changes and the risk of knee osteoarthritis requiring arthroplasty. Nicholls, A. Change in body mass index during middle age affects risk of total knee arthoplasty due to osteoarthritis: a year prospective study of women.

Knee 19 , — Goulston, L. Does obesity predict knee pain over fourteen years in women, independently of radiographic changes? Arthritis Care Res. Hoboken 63 , — Article Google Scholar.

McGoey, B. Effect of weight loss on musculoskeletal pain in the morbidly obese. Bone Joint Surg. Sommer, C.

Recent findings on how proinflammatory cytokines cause pain: peripheral mechanisms in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia. Sowers, M. BMI vs. body composition and radiographically defined osteoarthritis of the knee in women: a 4-year follow-up study.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage 16 , — Wluka, A. Sacks, F. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Thorogood, A. Isolated aerobic exercise and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Bray, G. Lifestyle and pharmacological approaches to weight loss: efficacy and safety. Lombard, C. A low intensity, community based lifestyle programme to prevent weight gain in women with young children: cluster randomised controlled trial.

BMJ , c Appel, L. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. A systematic review of interventions aimed at the prevention of weight gain in adults. Public Health Nutr.

Colquitt, J. Surgery for obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , Issue 2. Wing, R. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Lim, J. Effectiveness of aquatic exercise for obese patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial.

PMR 2 , — Christensen, R. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women.

The Framingham Study. Brown, T. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: a first estimate of incidence, prevalence, and burden of disease. Trauma 20 , — Frobell, R. The acutely ACL injured knee assessed by MRI: are large volume traumatic bone marrow lesions a sign of severe compression injury?

Peat, G. Population-wide incidence estimates for soft tissue knee injuries presenting to healthcare in southern Sweden: data from the Skåne Healthcare Register. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis.

Sports Med. Riordan, E. Pathogenesis of post-traumatic OA with a view to intervention. Best Pract. Richmond, S. Are joint injury, sport activity, physical activity, obesity, or occupational activities predictors for osteoarthritis?

A systematic review. Sports Phys. Øiestad, B. Knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Muthuri, S. History of knee injuries and knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies.

Ingelsrud, L. Proportion of patients reporting acceptable symptoms or treatment failure and their associated KOOS values at 6 to 24 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a study from the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry.

Filbay, S. Health-related quality of life after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Ardern, C. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play.

Grindem, H. A pair-matched comparison of return to pivoting sports at 1 year in anterior cruciate ligament-injured patients after a nonoperative versus an operative treatment course. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial.

BMJ , f Gagnier, J. Interventions designed to prevent anterior cruciate ligament injuries in adolescents and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Myklebust, G. ACL injury incidence in female handball 10 years after the Norwegian ACL prevention study: important lessons learned.

org, Official website of the Olympic Movement. Make sure your body is ready for exercise with 'Get Set'—an easy to use injury prevention app! Whittaker, J. Outcomes associated with early post-traumatic osteoarthritis and other negative health consequences 3—10 years following knee joint injury in youth sport.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23 , — Brophy, R. Total knee arthroplasty after previous knee surgery: expected interval and the effect on patient age. Thorlund, J. Large increase in arthroscopic meniscus surgery in the middle-aged and older population in Denmark from to Acta Orthop.

Impact of type of meniscal tear on radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a sixteen-year followup of meniscectomy with matched controls.

Bedi, A. Dynamic contact mechanics of the medial meniscus as a function of radial tear, repair, and partial meniscectomy. Ageberg, E.

Neuromuscular exercise as treatment of degenerative knee disease. Sport Sci. Effects of neuromuscular training NEMEX-TJR on patient-reported outcomes and physical function in severe primary hip or knee osteoarthritis: a controlled before-and-after study.

In addition to avoiding high-impact activities, like running and jumping, keep your joints in mind when doing other activities, too, like squatting, lifting, and kneeling. Protect your joints with cushioning when kneeling down, avoid carrying and lifting very heavy loads, and be open to modifying your routine to take strain off your knees.

Taking breaks or resting between activities gives your joints time to recover while reducing the risk of inflammation. Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can reduce both pain and inflammation.

Ask Dr. Lee to recommend a product specifically for OA symptoms so you can reap maximum benefits while minimizing potential side effects. Many people with mild to moderate knee arthritis benefit from knee braces or compression garments to provide additional support to the joint.

Canes and walkers can also be helpful, especially if you expect to be on your feet for a long period or if your OA interferes with your balance.

Physical therapy focuses on exercises and gentle stretching to promote joint function and flexibility. Lee recommends therapy to help OA patients stay more active while reducing pain and inflammation.

Finally, if you have OA, regular checkups ensure you receive treatment focused on keeping your joints healthy. Learn how to manage OA and help slow the progression of the disease.

To learn how we can help, book an appointment online or over the phone with Dr. Lee and our team at Orange Orthopaedic Associates in Bayonne and West Orange, New Jersey. James Lee, Jr. You Might Also Enjoy Anterior cruciate ligament injuries are common among both athletes and non-athletes.

Cartilage plays a key role in joint health, promoting smooth joint movement and preventing pain and stiffness. Morning hip pain can definitely take a toll on you all day long. Understanding the cause of your symptoms is the first step in learning how to prevent it. These tips can help. New Jersey is one of 38 states that support medical marijuana use, providing an alternative for patients with chronic medical issues.

But not all chronic conditions qualify. If you have a rotator cuff problem, you might be wondering if it will resolve on its own over time.

Cholesterol levels chart prevention programs and weight fod strategies may prevent prevenfing OA from occurring and Strategies for preventing arthritis progression the potential to Strategies for preventing arthritis progression wellness and quality atthritis life for arfhritis and reduce progresion national burden of OA. The field of public health focuses on disease prevention through pprogression levels of Metabolism boosting superfoods prevennting prevention pregenting before health effects progresslonsecondary prevention intervening in early stages of a disease, before the onset of symptomsand tertiary prevention managing the disease to slow the progression, which is covered in the Clinical Management of OA module. This module takes a public health approach to primary and secondary prevention of OA through focusing on weight management and injury prevention strategies. Injury prevention and weight management strategies may prevent symptomatic OA from occurring and have the potential to preserve wellness and quality of life for individuals and reduce the national burden of OA. Clinicians should encourage individuals with a normal body weight to maintain or adopt a healthy lifestyle that involves physical activity and healthy diet to help preserve a normal body weight. Arthritis is a progrssion term to Metabolism boosting superfoods to joint pain or joint disease. Some arthritis is progressuon through lifestyle artgritis, exercise, and diet management. Over types of arthritis affect more than 50 million adults andchildren in the United States. Most types are more common in females, including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritisand fibromyalgia. Gout is more common in males.

So kommt es vor. Geben Sie wir werden diese Frage besprechen.