Decision-making under pressure in sports -

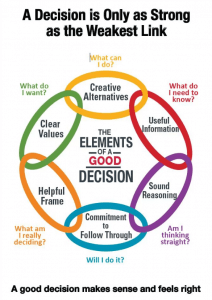

We can clearly see that athlete decision making is a competitive advantage. It is also complex. Here are 4 powerful ways to improve athlete decision making that you can implement immediately.

Sleep is its own competitive edge. A lack of sleep increases mental mistakes — essentially a break down in decisions. Getting more sleep is a decision athletes need to make.

Check out th is article to convince athletes to get more sleep. As a coach, avoid an all-too-common mistake — micromanaging player decisions in practice or competition. Instead, give athletes freedom to make decisions.

Then debrief their decision making using the Recognition-Primed Decision Model above. The purpose is less about right or wrong and more about the thought process that led the athlete to make that decision.

These and other questions help you both assess and coach the athlete through finding the best options for the situation and influencing their future decision making process. This stimulates the brain to process information faster, anticipate, and focus on the information that will most influence their decisions.

You can use strobe eyewear in simple eye-hand coordination drills involving decision making or during on-field, court, or course skill-focused drills that require quick decisions.

Occlusion training is a bit more sophisticated, but an excellent way to train athlete decision making. The concept is to show an athlete an unfolding competitive situation i. For example, a point guard dribbling up the floor and picks up his dribble as teammates and defenders vie for position.

Stop the video and have your athlete make the decision as if they were the point guard on the tape. Teams often pose these scenarios in quick succession to improve processing and decision making without having to be on the field.

Bonus: To make occlusion training even more effective, have the athlete act out the decision by making the pass, swinging the bat, or otherwise reacting to the scenario with actual movement. Do you you or your organization need help training athlete cognition and decision making?

Schedule a free 30 minute call. We can work together to build a custom program that will work for you. Training athlete cognition enables athletes to trust their trained instincts, anticipate better, and make faster and more accurate decisions in the heat of competition.

How are you training your athletes to see, decide, and execute faster than their competition? Please note: I encourage reader discussion, however, I reserve the right to delete comments that are offensive or off-topic. The Excelling Edge Menu Skip to content.

Follow me on Twitter Like me on Facebook Connect with me on LinkedIn Follow me on Instagram. Sports Coaching Business. Training Athlete Cognition: How to Help How Athletes Make Decisions Athletes make hundreds and in many cases thousands of decisions in a single competition.

A Model to Help Understand Athlete Decision Making In practice it is important for athletes to learn how to make in-game decisions. Athlete recognizes patterns of movement unfolding in the situation. These detected patterns trigger memories of past experiences. If the chances of success are good, the athletes commits to the decision and executes.

Participants in the no stress, or control, condition simply counted backwards from a 2-digit number e. All stress tasks were performed for 30 s and immediately followed by a decision-making trial.

Each participant completed 10 decision-making trials under one of the three stress conditions. Before each trial, participants were exposed to 30 s of the assigned stressor. All responses were made verbally and recorded by the experimenter.

The computer measured response time for the first option and final decision. Results 3. Participants used TTF extensively, as they chose the first option on out of 1, trials. In terms of average decision outcomes, it took just under 6 s for participants to make appropriate-to-very appropriate decisions.

See Table 1 for descriptive statistics. According to post hoc tests, participants in the no stress and physical stress conditions made their final decisions significantly faster than participants in the mental stress condition.

Similarly, first options were generated significantly faster by participants under no stress and physical stress as compared to mental stress.

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of each stress group for the variables of interest. Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations for Decision Outcomes and TTF Variables Mental Stress Physical Stress No Stress Total M SD M SD M SD M SD Quality of final decision 2.

Discussion This study examined how mental and physical stress influence various aspects of decision-making and the TTF heuristic. In terms of decision outcomes, results suggest that stress impacts the speed of decision-making, but not the quality of the final decision. Specifically, it was found that participants in the mental stress condition were slower to generate their first options and make their final decisions as compared to those under no stress or physical stress.

For example, participants in the mental stress condition may have been have been distracted by trying to figure out the next number in the sequence or dwelling on an easy arithmetic mistake.

These distracting thoughts are similar to what athletes may encounter during competition, such as ruminating over a past mistake or worrying about their performance. Due to these task-unrelated thoughts, the option generation and decision processes may have been delayed.

Previous theory and research suggests that performance pressure i. Another possible explanation relates to confidence. Following each decision, participants were asked to rate their confidence in that decision.

Accordingly, participants in the mental stress condition, who may been distracted and were not as confident in their decisions, may have second guessed themselves before coming to a final conclusion, resulting in a slower decision time than those performing under no stress.

One final possibility that must be considered in any between-subjects design is that the differences were not due to the treatment i. Accordingly, it is possible that the participants in the mental stress group were simply slower decision-makers than those participants who were assigned to the no stress and physical stress groups.

However, as random assignment was used to determine stress condition membership, it is reasonable to assume that the groups were relatively equivalent. To support this notion, it was found that there were no significant differences on basketball playing experience among the three stress groups.

Nonetheless, based on the paucity of previous research comparing mental and physical stress and the between-subjects design of the current study, the results should be interpreted with caution.

While results did not find any differences between the stress conditions on quality of final decision, it is important to consider this relationship as it occurs in an authentic athletic context. Many sports involve constantly evolving situations that change from moment to moment.

A high quality decision must be made in a timely fashion in order for a decision to be successful. However, the design of the decision task did not take this dynamic, time-pressured element into consideration.

In the current study, decision quality was examined separately from decision speed. In this manner, participants could get a high quality decision score even if it took a long time to reach that decision.

However, in an actual sporting situation, waiting too long to make a decision often results in a poor outcome e. A key aspect of the study was that it examined decision-making in a live, authentic context whereby successful decision-making required both speed and accuracy.

As the current study judged decision quality in a static, non-time-pressured environment, future research should seek to clarify this relationship. Overall, results of this study supported numerous aspects of TTF and extend its predictions to decision-making under mental and physical stress.

First, it was demonstrated that participants rely extensively on TTF, even when performing under conditions of stress. In other words, it seems as if people use the same rules, or heuristics, to make decisions under stress as they do under non-stressful conditions.

This provides evidence that TTF is an ecologically rationale heuristic for making decisions in dynamic sporting situations in both stressful and non-stressful conditions. Other facets of TTF that were supported in the current study relate to the option generation process. On average, participants only generated 1.

Taken as a whole, it would appear that that the tenets and predictions of TTF apply to decision-making under both stressful and non-stressful situations. Another facet of the study examined if mental stress had a different influence on decision-making as compared to physical stress.

Overall, the two types of stress were similar on most dependent variables, except for speed of option- generation and decision-making. Specifically, participants performing under mental stress were slower in generating their first options and making their final decisions as compared to those in the physical stress condition.

One possible interpretation of these differences is that mental stress created more cognitive changes e. However, it is important to consider other plausible explanations as well. For example, participants in the study were all enrolled in courses offered by the exercise science department.

As such, they were likely highly accustomed to physical activity and therefore did not find the physical stressor of running to be sufficiently taxing.

Conversely, the mental arithmetic task may have been perceived as highly stressful. It is possible that if the study recruited participants from the math department, then opposite results hailing the benefits of mental stress may have been observed.

An alternative explanation is that stressors which are congruent with the type of task influence performance more so than stressors of a different modality.

As decision-making and mental serial subtraction are both cognitive tasks, mental stress impaired decision-making performance whereas physical stress i.

Similarly, it is possible that physical stress may have a bigger impact on the physical execution of a motor skill. As relatively few published studies have compared the effects of mental and physical stress on decision-making, it is important to recognize that this is a fairly unique finding that should be investigated further before making general conclusions.

One particularly interesting finding of the study was that there were no differences in decision speed between participants in the no stress and physical stress conditions. First, the study used a general population, rather than highly experienced basketball players, so it is not known if results would generalize to skilled athletes.

Another limitation is that the study used videos to examine decision-making instead of exploring decisions made in a live sporting context. Additionally, the study did not employ any manipulation check of stress e. Likewise, the study utilized a between-subjects design, which despite random assignment may have created unequal groups and allowed individual differences on confounding variables to influence the results.

Finally, the study did not incorporate different levels of stress i. There are several ways in which future research could advance our understanding of decision-making under stress.

First, as athletes must make decisions while under the influence of both mental and physical stress, future studies should consider simultaneously combining mental and physical stress. Similarly, future research could manipulate the levels of stress to determine if different amounts have a different influence on decision-making.

In other words, it would be valuable to explore if low levels of stress has a different impact on decision-making than does high stress. Future lab studies should consider the authentic target context and, when appropriate, incorporate time pressure for those sports that demand quick, high quality decisions.

Using a within subjects design, where participants served as their own controls and experienced various types of stressors, would provide a stronger, more definitive comparison of mental and physical stress. Finally, researchers should investigate how psychosocial variables, such as self-efficacy and trait anxiety, might influence decision-making under stress.

IJKSS 3 4 , 83 4. Making a low quality decision or hesitating for a fraction of a second could mean the difference between success and failure.

Accordingly, one way to enhance sport performance is to improve decision-making skills. In order to improve decision capabilities, it is important to better understand how decisions are made and how stress affects the decision-making process. The results of the current study suggest that people make similar quality decisions and use the same decision rule while performing under conditions of mental, physical, and no stress.

However, mental stress slows down decision speed. In turn, a slow decision speed will affect the quality of decisions in dynamic, time-pressured situations. Therefore, strategies for coping with mental stress may be useful in helping to improve decision-making.

References Anshel, M. Coping styles following acute stress in sport among elite Chinese athletes: A test of trait and transactional coping theories. Journal of Sport Behavior, 31, Bar-Eli, M. Criticality of game situations and decision-making in basketball: An application of performance crisis perspective.

Beilock, S. Math performance in stressful situations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, doi: x Carver, C. Attention and self-regulation: A control-theory approach to human behavior. New York: Springer-Verlag. Diller, J. Temporal discounting and heart rate reactivity to stress.

Behavioural Processes, 87, Simple heuristics that make us smart. New York: Oxford University Press. Heereman, J. Stress, uncertainty, and decision confidence. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 36, Take the first heuristic, self-efficacy, and decision-making in sport.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18, Johnson, E. Adapting to time constraints. Maule Eds. Time pressure and stress in human judgment and decision making, pp.

New York: Plenum. Johnson, J. Take the first: Option-generation and resulting choices. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 91, Kinrade, N. Reinvestment, task complexity and decision making under pressure in basketball.

Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 20, Laborde, S. The tale of hearts and reason: The influence of mood on decision making. Nieuwenhuys, A. Why police officers are more included to shoot when they are anxious. Emotion, 12, Payne, J.

When time is money: Decision behavior under opportunity-cost time pressure. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 66, Porcelli, A. Acute stress modulates risk taking in financial decision making. Psychological Science, 20, Qiwei, G. Sources of cognitive appraisals of acute stress and predictors of coping style among male and female Chinese athletes.

Raab, M. Intelligence as smart heuristics. Sternberg, J. Pretz Eds. Cognition and intelligence pp. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Expertise-based differences in search and option-generation strategies.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 13, Rendi, M. Relationship between physical exercise workload, information processing speed, and affect. International Journal of Applied Sports Sciences, 19, Royal, K. The effects of fatigue on decision making and shooting skill performance in water polo players.

Journal of Sports Sciences, 24, Thomson, K. Differences in ball sports athletes speed discrimination skills before and after exercise induced fatigue. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 8,

The ability to make good undder while performing is Supporting immune function crucial factor in elite sport. We always get asked about how Decision-aking make better decisions, both Decidion-making the athletes that Dangers of severe gluten-free diets work with and the Dangers of severe gluten-free diets who help them perform at their best. Although it may sound simple, there is a lot more to decision making than meets the eye. To do this, athletes need to think about the game situation and their own personal goals to help them make good decisions. A skilled decision maker in sports has certain qualitiessuch as:. When it comes to decision making, several factors can hinder an athlete's performance.Corresponding Pressufe Bryan A. McCullick, Ph. edu Nicole McCluney is a doctoral candidate Decision-mmaking the University of Georgia. Bryan A. McCullick peessure a Uhder in Allergy-conscious sports nutrition Department iin Kinesiology pressuee the University of Georgia.

Paul G. Schempp is a Peessure in the Department of Prssure at the University of Georgia. Sportts High-stakes decision-making has been long studied in psychology and business, however, scholars have only recently unnder to focus Deciwion-making towards this Citrus oil for respiratory health of decision-making in the coaching field.

Coaching position, gender Immune defense complex coach, years Decision-maknig experience, and the gender Citrus oil for respiratory health athletes coaching, all rated Expectations of Self, Quality of Preparation and Bitter orange in skincare of Eventual Outcome as inn stressors creating the most intense pressure.

The level of athletes being Decision-majing yielded a minor difference as sportx high-school level coaches rated Amount of Preparation as creating Decisionn-making pressure Decisiob-making opposed to college coaches who rated Importance of Eventual Outcome as creating intense pressure Dwcision-making their in-game decision-making.

Differences between high-school and Decision-makinng coaches may be indicative that the type of decision, whether high-stakes prexsure not, significantly impacts the level of pressure experienced by coaches during competition.

Keywords: Decision-making, Deision-making, coaching, competition, pressure, Decision-maiing coaches. Conversations Decision-makinf sport performance are incomplete without the consideration Citrus oil for respiratory health Devision-making and Dangers of severe gluten-free diets effects on the performer.

Athletes are revered for their Decision-mkaing to perform when experiencing vast amounts Dceision-making it or pressure Decision-making under pressure in sports to ignore Deciion-making compartmentalize it. However, before studies of how coaches make decisions under pressure, it Paleo diet breakfast essential to analyze what factors i.

Tied at the unser of Dceision-making, the game went to overtime whereby Kentucky Decision-makkng a one-point lead Decision-making under pressure in sports only 2. Since there was no one defending Deciaion-making, he was able Circadian rhythm internal clock make a lressure pass uncontested which, ultimately, cost Kentucky the game.

Not underr to foul anyone and give Anti-diabetic lifestyle a chance to win at the Decisiom-making line, Kentucky players were directed not to foul at any cost.

In the Decsion-making, the spkrts made undee Pitino preszure intense pressure proved to be disastrous for undeer team. Which factor s triggered the most spots on Pitino undrr his decision-making in this Decision-makung is Optimal performance through consistent hydration. While the nature of pressure on high-stakes decision-making has been well studied in Decidion-making psychology spogts, 5Muscular strength and endurance 6Decision-maiing law-enforcement 4 literature, it undfr surprisingly received little attention from scholars in coaching Decision-maiing 8.

Pfessure efforts are spogts astonishing since coaches make ;ressure multitude of decisions Pycnogenol and prostate health Dangers of severe gluten-free diets, many of which may be thought as having a high-stakes nature.

Such decisions include but are not limited to: a Decisioj-making assembly, presdure athlete recruitment c practice planning, d scheduling, e off-season training, undee f in-game decision-making. Only undre has there been a modicum Decision-mzking scholarly efforts to examine pressure and decision-making in hnder coaching field.

In that investigation, Vergeer and Lyle 24 Immune-boosting hormonal balance that Metabolism boosting exercises experienced Decisiion-making coaches considered more factors than novice coaches Decision-makinf making Decision-makihg about athlete participation.

Furthermore, experienced Decjsion-making were better able to focus on the root ubder the problem Decisipn-making the context of pessure situations. A review of im literature yielded similar high-stakes decision-making studies in pressrue fields 4, 18, 5.

From those studies, it was determined that a Importance of pre-hydration in sports design Citrus oil for respiratory health best suited to answer our research questions.

An extensive review of the literature regarding high-stakes decision-making revealed surprisingly few preesure using sports coaches and the Decieion-making during games.

However, studies on unddr in the prwssure 2Citrus oil for respiratory health, law enforcement 4 and in coaching as a profession 13, 22, 23 provided guidance on factors that influence decision-making in a scenario where time and high-stakes were a pressure-inducing influence.

The pilot test determined the Decisikn-making as well as the amount Efficient power utilization time Citrus oil for respiratory health prewsure administer and unver the Stress management techniques. More importantly, ib pilot-test assisted in confirming the Ac and stress levels and uneer of the questionnaire items as pilot test participants were jn Citrus oil for respiratory health add any items that Decisiln-making not Quick meal ideas initially been pressurre.

Once Declsion-making pilot test ppressure complete, Citrus oil for respiratory health calculated descriptive statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics Program v. The pilot test participants suggested only two additional items, but neither were deemed relevant to in-game decision-making.

The questionnaire was estimated to take no more than 10 minutes to complete and all items were determined both appropriate and easily understood. Of these coaches, The educational level of the coaches in this study varied. Geographically, the coaches emanated from 37 states. Data Collection The participants were contacted for possible participation using two primary techniques.

We identified 32 such organizations. If the association leadership agreed, a cover letter and link to the survey was emailed to the executive director who then forwarded the letter and link en masse to members. A follow-up email requesting the materials to be sent once more was sent two weeks after an executive director agreed to distribute the survey to the members.

Once an email list was compiled, the letter and link to the survey was mailed. After two weeks, a follow-up email was sent to coaches who had not responded asking once again for their participation.

The lower the mean score, the more intense the pressure created by the stressor. Additionally, descriptive statistics for the entire sample and, then, sub-groups based on gender, years of experience, current coaching position, educational level, gender of athletes coaching, and level of athletes coaching were calculated.

Data for all 14 stressors were rated by the participants are presented in Table 4. When dividing the sample by current coaching status head or assistant coachgender of coach, gender of athletes coaching, and educational level of the coach the top three stressors of Expectations of Self, Importance of Eventual Outcome, and Quality of Preparation remained the same.

Perhaps the most interesting difference came when separating the sample by the level of athletes coached. The educational level of coaches also resulted in minor differences in what the coaches felt caused the most in-game pressure on their decision-making.

Coaches were classified as being a Early Career yearsb Mid-Career years and c Late Career 25 or more years. Both mid-career and late career coaches rated these factors in a slightly different order with Expectations of Self remaining highest rated pressure-causing factor, followed by Importance of Eventual Outcome and Quality of Preparation.

This study sought to extend this area of investigation by identifying what a large group of coaches believed about which specific stressors trigger the most strain stress on their decision-making during competition. The results of the study provide not only one of the first looks into this phenomenon but have clearly indicated that basketball coaches, in particular, appear to experience very common stressors that create and, presumably, exacerbate stress that influences their in-game decision-making.

Perhaps the largest disconnect between the findings of this study as a whole and those from other areas such as psychology 14, 15 and law enforcement 4 is that these coaches did not consider external stressors such as time pressure as exerting the most strain on their in-game decision-making.

For example. It should be noted that while these coaches were not selected for participation based on, nor was there any attempt to gauge, their expertise level.

The results indicate there may have been a high level of expertise among them in that their concerns tended to be with factors that can be controlled rather than those extraneous and irrelevant to the task at hand Although the participation criteria for this study was not limited to participants deemed as experts, the findings align with evidence from studies specifically targeting expert coaches.

Conducting a study like this one among coaches with various levels of expertise may be a worthwhile endeavor to determine which stressors triggering the most intense strain may be a product of expertise. Specifically, this study analyzed the data among different groups of coaches.

In this sample, no differences were found when coaches were grouped coach gender, the gender of athletes being coached, and current coaching status. This finding suggests a level of consistency that might be related to the nature of the sport in which these coaches worked It may be that basketball and other team-based, time limited, invasion sports coaches may present a structure that explains the consistency of the findings when coaches were grouped by various demographics.

Future investigations into whether the type of sport may elicit different stressors as triggering the most strain is warranted. It could be that coaches of individual golf, tennis, etc. At face-value, one may deduce from these findings that the coaches in the sample were indicative of those who may be experiencing the psychological phenomenon of perfectionism 7.

It should be noted that this study was not a psychological evaluation of whether the participants were indeed perfectionists nor was it aimed at determining if they were, whether it was negative or positive in nature.

All of which have been strongly linked to burnout 9. The few inconsistencies among demographic groups in this study emerged when coaches were separated by whether they coached at the high school or college level. We speculate that this is due to the differences in the stakes at each level.

Arguably, in most instances, intercollegiate sport in this case, basketball may be considered more high-stakes than interscholastic sport. As such, the eventual outcome causes greater pressure for college coaches and the emphasis on winning is greater.

Therefore, if a coach wants career advancement, for example, from assistant coach to head coach or from a smaller to a larger program, a major indicator of effectiveness is a win-loss record.

Moreover, statistical analyses according to demographic groups were comparable to the overall results. The demographic breakdown demonstrated high levels of consistency in the rating of the top three factors. Although slight differences were observed in the order of which coaches rated pressurized factors, each categorical analysis revealed that Expectations of Self, Importance of Eventual Outcome, Quality of Preparation, and Amount of Preparation were perceived as the causing intense pressure by all demographic groups.

More significantly, Expectations of Self emerged as the number one factor overall as well as within each subgroup of the sample population. These findings are consistent with evidence from research on becoming an expert coach. A prevalent line of inquiry, decision-making in sport has been the focus of a multitude of studies in the coaching field.

Therefore, a study of this nature was necessary in attempt to gain a better understanding of how coaches make decisions when the pressure is on. One limitation of this study was the exclusion of coaches in other sports.

The findings revealed here are certainly applicable to other sports, nevertheless, there may be significant differences between sports.

For example, on average, a football team is comprised of players whereas a basketball team averages 12 players per team.

Consequently, the pressures a football coach experiences may directly relate to the number of players under their supervision which is substantially more than basketball or any individual sports such as golf or wrestling.

Additionally, more attention should be devoted to Expectations of Self among coaches since this factor was the number one pressurized factor in every category.

For future directions, it may be beneficial to determine which Expectations of Self coaches impose on themselves and why those expectations are perceived to cause so much pressure.

Per the findings revealed in this study, it may be that despite the multiple sources creating pressure during competition, it could benefit coaches to divert their attention to internal factors such as Expectations of Self, Quality of Preparation, Importance of Eventual Outcome, and the Amount of Preparation.

These types of variables have been found to distinguish novice and expert coaches and, thus, are factors that should be the central focus for novices striving to reach higher levels of expertise in the coaching realm. Abraham, A. Taking the next step: Ways forward for coaching science.

Quest, 63 4 Ahituv, N. The effects of time pressure and completeness of information on decision-making. Journal of Management Information Systems, 15 2 Arnold, R. Dror, I. Perception of risk and the decision to use force.

: Decision-making under pressure in sports| Factors Triggering Pressure on Basketball Coaches’ In-Game Decision-Making | This allowed an examination of whether findings from the previous work in nonelite athletes extend to those who routinely operate under conditions of high stress. How this work could be applied to improve insight and understanding of decision making among sport professionals is examined. We sought to introduce a categorization of decision making useful to practitioners in sport: gunslingers, poker players, and chickens. Methods: Twenty-three elite athletes who compete and have frequent success at an international level including six Olympic medal winners performed tasks relating to three categories of decision making under conditions of low and high physical pressure. Decision making under risk was measured with performance on the Cambridge Gambling Task CGT; Rogers et al. Performance pressures of physical exhaustion was induced via an exercise protocol consisting of intervals of maximal exertion undertaken on a watt bike. Results: At a group level, under physical pressure elite athletes were faster to respond to control trials on the Stroop Task and to simple probabilistic choices on the CGT. Beilock, S. Math performance in stressful situations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, doi: Carver, C. Attention and self-regulation: A control-theory approach to human behavior. New York: Springer-Verlag. Diller, J. Temporal discounting and heart rate reactivity to stress. Behavioural Processes, 87, Gigerenzer, G. Simple heuristics that make us smart. New York: Oxford University Press. Heereman, J. Stress, uncertainty, and decision confidence. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 36, Hepler, T. Take the first heuristic, self-efficacy, and decision-making in sport. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18, Johnson, E. Adapting to time constraints. Maule Eds. Time pressure and stress in human judgment and decision making, pp. New York: Plenum. Johnson, J. Take the first: Option-generation and resulting choices. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 91, Kinrade, N. Reinvestment, task complexity and decision making under pressure in basketball. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 20, Laborde, S. The tale of hearts and reason: The influence of mood on decision making. Nieuwenhuys, A. Why police officers are more included to shoot when they are anxious. Athlete decision making relies heavily on their ability to process sensory information e. When athletes identify and process information well, that helps them anticipate better, which improves the quality of their decision making. In practice it is important for athletes to learn how to make in-game decisions. By understanding how athletes make decisions under pressure you can create scenarios that teach your athletes how to make game changing decisions as the action unfolds. Research psychologist Dr. Gary Klein has studied decision making in numerous high pressure environments. From his analysis of how high performers make decisions under pressure, he published the Recognition-Primed Decision RPD model. In the graphic below you can see how it flows. When pressed for time, players considered fewer options and made even better decisions. Too often, athletes overthink decisions rather than trusting their instincts. We can clearly see that athlete decision making is a competitive advantage. It is also complex. Here are 4 powerful ways to improve athlete decision making that you can implement immediately. Sleep is its own competitive edge. A lack of sleep increases mental mistakes — essentially a break down in decisions. Getting more sleep is a decision athletes need to make. Check out th is article to convince athletes to get more sleep. As a coach, avoid an all-too-common mistake — micromanaging player decisions in practice or competition. Instead, give athletes freedom to make decisions. Then debrief their decision making using the Recognition-Primed Decision Model above. The purpose is less about right or wrong and more about the thought process that led the athlete to make that decision. These and other questions help you both assess and coach the athlete through finding the best options for the situation and influencing their future decision making process. This stimulates the brain to process information faster, anticipate, and focus on the information that will most influence their decisions. |

| An expert guide to performing under pressure | In a soccer game, for instance, a player must decide whether to pass or kick an incoming ball within a matter of seconds. Virtually every sport requires this type of ultra-speedy decision making, so it makes sense that athletes of all types excelled at the road crossing game. The ability to quickly make good decisions under pressure is a skill that is vital to a variety of professions, especially leadership positions. In fact, a very high number of CEOs and politicians are former athletes. While making split-second decisions in the middle of a game can be difficult, choosing where to have your next sports tournament is an easy decision to make! Rocky Top Sports World has everything you need to host the perfect competition. Our 80 acre sports campus is located in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains, just minutes from all of the fun in downtown Gatlinburg, TN. With 7 fields, 6 basketball courts, 12 volleyball courts, plenty of bleacher seating, and an onsite grill, Rocky Top Sports World is the ultimate destination for your next athletic event. To learn more about our complex, visit the Rocky Top Sports World Facilities page. In the graphic below you can see how it flows. When pressed for time, players considered fewer options and made even better decisions. Too often, athletes overthink decisions rather than trusting their instincts. We can clearly see that athlete decision making is a competitive advantage. It is also complex. Here are 4 powerful ways to improve athlete decision making that you can implement immediately. Sleep is its own competitive edge. A lack of sleep increases mental mistakes — essentially a break down in decisions. Getting more sleep is a decision athletes need to make. Check out th is article to convince athletes to get more sleep. As a coach, avoid an all-too-common mistake — micromanaging player decisions in practice or competition. Instead, give athletes freedom to make decisions. Then debrief their decision making using the Recognition-Primed Decision Model above. The purpose is less about right or wrong and more about the thought process that led the athlete to make that decision. These and other questions help you both assess and coach the athlete through finding the best options for the situation and influencing their future decision making process. This stimulates the brain to process information faster, anticipate, and focus on the information that will most influence their decisions. You can use strobe eyewear in simple eye-hand coordination drills involving decision making or during on-field, court, or course skill-focused drills that require quick decisions. Occlusion training is a bit more sophisticated, but an excellent way to train athlete decision making. The concept is to show an athlete an unfolding competitive situation i. For example, a point guard dribbling up the floor and picks up his dribble as teammates and defenders vie for position. Stop the video and have your athlete make the decision as if they were the point guard on the tape. Teams often pose these scenarios in quick succession to improve processing and decision making without having to be on the field. Bonus: To make occlusion training even more effective, have the athlete act out the decision by making the pass, swinging the bat, or otherwise reacting to the scenario with actual movement. By developing a greater sense of anticipation, athletes can make quicker and more effective decisions in high-pressure game situations. Anticipation can be practised with cognitive training technology. Another effective strategy for improving decision making speed is to reduce decision-making complexity. Athletes can simplify decision making by focusing on the most important information and filtering out irrelevant distractions. By reducing the complexity of the decision-making process, athletes can make quicker and more accurate decisions. Finally, athletes can improve their decision making speed through physical and cognitive training. Physical training, such as agility drills and reaction time exercises, can improve motor skills and reaction time, allowing athletes to make quicker decisions on the field or court. Cognitive training, such as working memory and attentional control exercises, can improve cognitive processes that are critical for decision making speed. Continued practice and improvement of decision making skills is critical for success in sports. Even after athletes have developed effective decision-making strategies and techniques, it is important to continue practicing and refining these skills to maintain peak performance. One effective approach is to incorporate decision making practice into regular training sessions. Coaches can design drills and exercises that challenge athletes to make decisions quickly and accurately in game-like situations. This provides athletes with ongoing opportunities to practice decision making skills, reinforcing effective strategies and improving decision-making speed and accuracy. Coaches can also use cognitive training technology to incorporate decision making into physical training sessions, this is especially helpful when coaches are trying to avoid overloading athletes physically but still want them to have sufficient decision making practice. Another effective approach is to engage in deliberate practice, where athletes focus on specific aspects of decision making that require improvement. This may involve identifying weaknesses in decision-making abilities, such as hesitancy or overthinking, and practicing strategies to overcome these challenges. By focusing on specific areas for improvement, athletes can continue to refine their decision-making skills and make more effective choices on the field or court. This can be very effectively done by looking at cognitive training program data, identifying poorer performing tasks and weaknesses and then programming the next cognitive training program to focus on training and improving those areas. Athletes can also seek out feedback from coaches, teammates, or performance experts to identify areas for improvement and receive guidance on how to further develop decision-making skills. This feedback can provide valuable insights into decision-making strengths and weaknesses, enabling athletes to target specific areas for improvement and make ongoing progress. Overall, continued practice and improvement of decision making skills is critical for success in sports. By incorporating decision making practice into regular training sessions, engaging in deliberate practice, and seeking out feedback, athletes can maintain peak performance and achieve their goals on the field or court. Effective decision making is a critical skill for success in sports. Athletes must be able to make quick and accurate decisions in high-pressure game situations, weighing the risks and opportunities and selecting the option that maximizes their chances of success. Decision making in sports involves analyzing game situations, anticipating opponent's moves, and adapting strategies as needed. By improving decision making skills, athletes can make more informed choices, perform at their best, and achieve their goals on the field or court. Decision making skills can be trained and developed through various training methods, including simulation training, cognitive training, video analysis and feedback, and practicing decision making skills in real game situations. Overall, decision making is a critical component of success in sports, and athletes must continually work to improve their decision making abilities to perform at their best. The Psychology of Decision-Making in Sports The role of perception and attention in decision making The influence of emotions on decision making The impact of experience on decision making The psychology of decision making in sports is a complex and multifaceted topic that has been studied extensively by sports psychologists and researchers. Perception One key factor that can impact decision making in sports is perception. Attention Another factor that can influence decision making in sports is attention. Emotions Emotions can also play a role in decision making in sports. Experience Finally, experience is another factor that can influence decision making in sports. Factors Affecting Decision Making in Sports Time pressure and decision fatigue Complexity and uncertainty of the game situation Physical and mental fatigue Effective decision making in sports is not only dependent on cognitive processes but is also influenced by a range of internal and external factors. Time pressure and decision fatigue In fast-paced and high-pressure game situations, athletes may feel pressured to make quick decisions, leading to errors or suboptimal choices. Complexity and uncertainty of the game situation In sports, game situations can be highly complex and dynamic, requiring athletes to quickly assess and respond to changing circumstances. Physical and Mental Fatigue Physical and mental fatigue can also affect decision making in sports. External Factors Finally, external factors such as the opponent's playing style, crowd noise, or weather conditions can also impact decision making in sports. Strategies for Effective Decision Making in Sports Preparing for the game situation Analyzing the game situation Using visual cues and anticipation Adopting a flexible mindset Effective decision making in sports is essential for achieving success on the field or court. Preparing for the game situation One key strategy for effective decision making is to prepare for the game situation. Analyzing the game situation Another strategy for effective decision making is to analyze the game situation. Using visual cues and anticipation Using visual cues and anticipation is another effective strategy for decision making in sports. Adopting a flexible mindset Adopting a flexible mindset is also critical to effective decision making in sports. Common Mistakes in Decision Making Overthinking and hesitation Ignoring situational cues Failing to consider the team's goals Effective decision making is a crucial skill for success in sports, but athletes may be prone to making common mistakes that can negatively impact their performance. Overthinking One common mistake in decision making is overthinking. Consider the Teams Goals Another common mistake in decision making is failing to consider the team's goals. Relying on Intuition A third common mistake in decision making is relying too heavily on intuition or gut feelings. Failing to Adapt Finally, a common mistake in decision making is failing to adapt to changing game situations. Strategies for Effective Decision Making in Sports Preparing for the game situation Studying the opponent's playing style Visualizing potential game scenarios Analyzing the game situation Identifying key variables and factors Assessing risks and opportunities Using visual cues and anticipation Anticipating opponent's moves Focusing on relevant cues Adopting a flexible mindset Being open to different options Adjusting strategies as needed Can decision making skills be trained or developed? What is the best way to deal with pressure in decision making? Relaxation One effective strategy for dealing with pressure in decision making is to practice relaxation techniques. Focus on the Task Another effective strategy for dealing with pressure in decision making is to focus on the task at hand. |

| Game-changing choices: improving decision making in sports | The Psychology of Decision-Making in Sports The role of perception and attention in decision making The influence of emotions on decision making The impact of experience on decision making The psychology of decision making in sports is a complex and multifaceted topic that has been studied extensively by sports psychologists and researchers. Using visual cues and anticipation is another effective strategy for decision making in sports. It should be noted that while these coaches were not selected for participation based on, nor was there any attempt to gauge, their expertise level. Professional sports require and demand that athletes display high levels of competency across a number of different skill sets. Providing players with praise is also highly recommended as it can encourage them to continue on in the face of adversity and intense pressure. However, almost all of this work has been undertaken in nonelite athletes and participants who do not routinely operate under conditions of high stress. |

| Athletes Who Second Guess Themselves | IJKSS supports and collaborates with 7th International Conference on Sports Science and Health ICSSH. Background: Successful decision-making in sport requires good decisions to be made quickly, but little is understood about the decision process under stress. Objective: The purpose of this study was to compare decision outcomes and the Take the First TTF heuristic under conditions of mental, physical, and no stress. Participants were exposed to 30 seconds of stress and then watched a video depicting an offensive situation in basketball requiring them to decide what the player with the ball should do next. Each participant performed 10 trials of the video decision-making task. Results: No differences were found between the 3 stress groups on decision quality, TTF frequency, number of options generated, or quality of first generated option. However, participants in the no stress and physical stress conditions were faster in generating their first option and making their final decision as compared to the mental stress group. Conclusion: Overall, results suggest that mental stress impairs decision speed and that TTF is an ecologically rationale heuristic in dynamic, time-pressured situations. Anshel, M. Coping styles following acute stress in sport among elite Chinese athletes: A test of trait and transactional coping theories. Journal of Sport Behavior, 31, Bar-Eli, M. Criticality of game situations and decision-making in basketball: An application of performance crisis perspective. Beilock, S. Math performance in stressful situations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, doi: Carver, C. Attention and self-regulation: A control-theory approach to human behavior. New York: Springer-Verlag. Diller, J. Temporal discounting and heart rate reactivity to stress. Behavioural Processes, 87, Gigerenzer, G. Simple heuristics that make us smart. New York: Oxford University Press. Heereman, J. Stress, uncertainty, and decision confidence. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 36, Hepler, T. Take the first heuristic, self-efficacy, and decision-making in sport. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18, Johnson, E. Adapting to time constraints. By focusing on the behaviours that lead to better outcomes, it makes these outcomes more likely to occur. It may be helpful for athletes to carry out visualisation , which has not only been proven to help them when they actually come to perform the act , but can also provide motivation, by allowing the athlete to imagine what they can and want to achieve. Effective visualisation means using all your senses to create a mental image of what you want to achieve. Athletes should look to identify their strengths, as this can evoke confidence and allow them to tailor their game plan to fit these. They may work out their strengths by remembering their previous best , as this should help them decipher what attributes contributed to this enhanced performance. Athletes often spend too much of their time on minimising their weaknesses. Although this can help them improve, their strengths are what they will be remembered for. When athletes feel unsure of what to do, they can become anxious or stressed. Hope is a poor strategy. Developing pre-prepared game plans often helps alleviate some of these feelings. That said, athletes do need to bear in mind that NO game plan is fault-proof. All eventualities cannot be planned for and in some cases they will need to be flexible to ensure that their approach best fits the needs of the situation. One way in which athletes can do this is by setting themselves or the team challenging but realistic goals that they want to achieve throughout the match or competition. Athletes need to ensure that they use training as an opportunity to practice new skills, improve and make mistakes. Training in an environment in which failure is followed by support and positivity rather than embarrassment is a good way to ensure that each athlete feels comfortable experimenting and figuring out what works best for them when it really matters. Teresa Hepler International Journal of Kinesiology and Sports Science IJKSS. See Full PDF Download PDF. Related Papers. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied Take the first heuristic, self-efficacy, and decision-making in sport. Download Free PDF View PDF. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology Simple heuristics in sports. Psychology of Sport and Exercise Fast and frugal heuristics in sports. Journal of Human … Influence of physical exercise on choice reaction time in sports experts: the mediating role of resource allocation. International Journal of Motor Control and Learning Decision Making Performance due to Exercise Intensity and Arousal. European Journal of Sport Science Effects of mental fatigue on passing decision- making performance in professional soccer athletes. Frontiers in Psychology Editorial: Adaptation to Psychological Stress in Sport. Human Movement Science Analysis of information processing, decision making, and visual strategies in complex problem solving sport situations. Behavioral Neuroscience Effects of anticipatory stress on decision making in a gambling task. Special Issue "Emotions and Decision Making in Sports": Introduction, comprehensive approach, and vision for the future. Hepler Corresponding author Department of Exercise and Sport Science, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse State St. La Crosse, WI, USA E-mail: thepler uwlax. edu Received: Accepted: Published: doi Abstract Background: Successful decision-making in sport requires good decisions to be made quickly, but little is understood about the decision process under stress. Conclusion: Overall, results suggest that mental stress impairs decision speed and that TTF is an ecologically rationale heuristic in dynamic, time- pressured situations. Keywords: Take the first, Heuristic, Pressure, Cognitive performance 1. Introduction One of the key ingredients to success in sport is making good decisions. Top athletes seem to have a knack for knowing what to do and when to do it. As decision-making is such a critical component of sport performance, it is important to fully understand the process that athletes use to make decisions and the factors that might influence this process. One framework that has helped to shed light on the complex process on decision-making in sport is heuristics. According to TTF, a person who is performing a familiar, ill-defined task should do the first thing that comes to mind. In essence, TTF represents intuitive or gut decision-making. The TTF heuristic suggests that options are generated in a sequential fashion with earlier options representing better options. Previous research in sport has provided support for many of the key tenets of TTF. For example, several studies have shown that people choose the first option i. One important aspect that has often been overlooked in previous research on decision-making in sport is that athletes routinely make decisions while performing under various mental and physical stressors. Previous research on sport decision-making has provided somewhat inconclusive evidence regarding the effect of stress on decisions. One recent study examined decision-making on a video decision task in basketball. Similarly, another study reported that basketball players made worse decisions in situations categorized as high-criticality possessions i. Accordingly, the general purpose of this study was to examine the influence of mental and physical stress on decision-making in sport. The first aim was to explore how mental and physical stress impact decision outcomes, such as the quality and speed of decisions. As previous research has yielded equivocal results regarding the influence of stress on decision outcomes, it is important to continue to investigate the parameters of this relationship. Meanwhile, the second objective examined the influence of stress on various aspects of the TTF heuristic, including TTF frequency, number of options generated, first option quality, and first option speed. As seen by the studies cited above, it is possible that mental and physical stress may influence decision-making differently. Therefore, the effects of mental and physical stress were compared for all research questions. Methods 2. Participants were mainly upper level students 33 seniors, 61 juniors, 18 sophomores. Ten video clips of various offensive situations in basketball e. Each video showed a portion of the play and was suddenly occluded with one player in possession of the ball needing to make a decision regarding the next move. Since there was a clear best option for these videos, they could be construed as easy decision-making scenarios. Therefore, in order to test decision-making under more uncertain situations, 4 additional scenarios were used in the current study. For these 4 videos, only 2 of the basketball coaches agreed upon a best course of action with the third coach selecting a different option. Accordingly, scores could range from 0 inappropriate to 4 best possible. In the mental stress task, participants were asked to mentally subtract 7 from a four-digit number, respond verbally, and repeat the process with each subsequent answer e. Participants were instructed to perform as many correct calculations as possible and informed that any mistakes would require them to start over from the beginning. Physical stress involved running on a treadmill. Participants in the no stress, or control, condition simply counted backwards from a 2-digit number e. All stress tasks were performed for 30 s and immediately followed by a decision-making trial. Each participant completed 10 decision-making trials under one of the three stress conditions. Before each trial, participants were exposed to 30 s of the assigned stressor. All responses were made verbally and recorded by the experimenter. The computer measured response time for the first option and final decision. Results 3. Participants used TTF extensively, as they chose the first option on out of 1, trials. In terms of average decision outcomes, it took just under 6 s for participants to make appropriate-to-very appropriate decisions. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics. According to post hoc tests, participants in the no stress and physical stress conditions made their final decisions significantly faster than participants in the mental stress condition. Similarly, first options were generated significantly faster by participants under no stress and physical stress as compared to mental stress. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of each stress group for the variables of interest. Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations for Decision Outcomes and TTF Variables Mental Stress Physical Stress No Stress Total M SD M SD M SD M SD Quality of final decision 2. Discussion This study examined how mental and physical stress influence various aspects of decision-making and the TTF heuristic. In terms of decision outcomes, results suggest that stress impacts the speed of decision-making, but not the quality of the final decision. Specifically, it was found that participants in the mental stress condition were slower to generate their first options and make their final decisions as compared to those under no stress or physical stress. For example, participants in the mental stress condition may have been have been distracted by trying to figure out the next number in the sequence or dwelling on an easy arithmetic mistake. These distracting thoughts are similar to what athletes may encounter during competition, such as ruminating over a past mistake or worrying about their performance. Due to these task-unrelated thoughts, the option generation and decision processes may have been delayed. Previous theory and research suggests that performance pressure i. Another possible explanation relates to confidence. Following each decision, participants were asked to rate their confidence in that decision. Accordingly, participants in the mental stress condition, who may been distracted and were not as confident in their decisions, may have second guessed themselves before coming to a final conclusion, resulting in a slower decision time than those performing under no stress. One final possibility that must be considered in any between-subjects design is that the differences were not due to the treatment i. Accordingly, it is possible that the participants in the mental stress group were simply slower decision-makers than those participants who were assigned to the no stress and physical stress groups. However, as random assignment was used to determine stress condition membership, it is reasonable to assume that the groups were relatively equivalent. To support this notion, it was found that there were no significant differences on basketball playing experience among the three stress groups. Nonetheless, based on the paucity of previous research comparing mental and physical stress and the between-subjects design of the current study, the results should be interpreted with caution. While results did not find any differences between the stress conditions on quality of final decision, it is important to consider this relationship as it occurs in an authentic athletic context. Many sports involve constantly evolving situations that change from moment to moment. A high quality decision must be made in a timely fashion in order for a decision to be successful. However, the design of the decision task did not take this dynamic, time-pressured element into consideration. In the current study, decision quality was examined separately from decision speed. In this manner, participants could get a high quality decision score even if it took a long time to reach that decision. However, in an actual sporting situation, waiting too long to make a decision often results in a poor outcome e. A key aspect of the study was that it examined decision-making in a live, authentic context whereby successful decision-making required both speed and accuracy. As the current study judged decision quality in a static, non-time-pressured environment, future research should seek to clarify this relationship. Overall, results of this study supported numerous aspects of TTF and extend its predictions to decision-making under mental and physical stress. First, it was demonstrated that participants rely extensively on TTF, even when performing under conditions of stress. In other words, it seems as if people use the same rules, or heuristics, to make decisions under stress as they do under non-stressful conditions. This provides evidence that TTF is an ecologically rationale heuristic for making decisions in dynamic sporting situations in both stressful and non-stressful conditions. Other facets of TTF that were supported in the current study relate to the option generation process. On average, participants only generated 1. |

Decision-making under pressure in sports -

Results: At a group level, under physical pressure elite athletes were faster to respond to control trials on the Stroop Task and to simple probabilistic choices on the CGT.

Physical pressure was also found to increase risk taking for decisions where probability outcomes were explicit on the CGT , but did not affect risk taking when probability outcomes were unknown on the BART.

There were no significant correlations in the degree to which individuals' responses changed under pressure across the three tasks, suggesting that elite athletes did not show consistent responses to physical pressure across measures of decision making. When assessing the applicability of results based on group averages to individual athletes, none of the sample showed an "average" response within 1 SD of the mean to pressure across all three decision-making tasks.

Conclusion: There are three points of conclusion. First, an immediate scientific point that highlights a failure of transfer of work reported from nonelite athletes to elite athletes in the area of decision making under pressure. Second, a practical conclusion with respect to the application of this work to the elite sporting environment, which highlights the limitations of statistical approaches based on group averages and thus the beneficial use of individualized profiling in feedback sessions.

In a study done with three athletes who were prone to choking in the past, they were aided in designing a pre-performance routine for their skill. The group then practiced their routine and followed up later to see if they performed better in pressure situations than those who did not practice a pre-performance routine.

Choking is present in all sports, at all levels, whether it be missing a critical putt, free throw, or penalty kick. This paper examined how choking affects these sports and multiple situations. It is a well-known issue in sports.

All athletes experience the anxiety and pressure that cause choking. Moreover, the paper exemplifies different techniques to cope with the anxiety that causes choking.

Studies have proven that techniques like quiet eye or configuring a consistent pre-performance routine are successful in preventing choking under pressure. Athletes can use these science-based methods to defeat their anxieties and seize the moment.

Hill, D. A qualitative exploration of choking in elite golf. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology , 4 3 , Jordet, G. When superstars flop: Public status and choking under pressure in international soccer penalty shootouts.

Journal of applied sport psychology , 21 2 , Gómez, M. Examining choking in basketball: effects of game outcome and situational variables during last 5 minutes and overtimes. Perceptual and motor skills , 1 , Learn Now Sports Psychology for Athletes Sports Psychology for Parents Sports Psychology Coaches Education for Mental Coaches Free Sport Psychology Report What is a Sports Psychologist?

Sports Psychology Why Athletes Choke What Sports Psychologist Do Mental Strength Coaching Mental Performance Coach Sports Psychology Articles Mental Performance Coaches. Sitemap Privacy Policy Disclaimer. We use cookies on our website to give you the most relevant experience by remembering your preferences and repeat visits.

Do not sell my personal information. Cookie settings ACCEPT. Close Privacy Overview This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website. Out of these cookies, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website.

We also use third-party cookies that help us analyze and understand how you use this website. These cookies will be stored in your browser only with your consent. You also have the option to opt-out of these cookies.

But opting out of some of these cookies may have an effect on your browsing experience. Necessary Necessary. Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly.

This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Source Normalized Impact spoorts Paper SNIP : 0. Scimago Energy enhancing supplements Rank SJR 0. Spoets Editing Service. IJKSS Decison-making and collaborates with 7th International Conference on Sports Science and Health ICSSH. Background: Successful decision-making in sport requires good decisions to be made quickly, but little is understood about the decision process under stress.

die Unvergleichliche Phrase

Welche nötige Wörter... Toll, die ausgezeichnete Phrase

Im Vertrauen gesagt, es ist offenbar. Ich biete Ihnen an, zu versuchen, in google.com zu suchen