Satiety and food cravings -

University of Liverpool provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK. Food cravings are very familiar to most people. We may see or smell food and want to eat, or sometimes we suddenly feel like eating something delicious. However, eating is much more than just responding to a biological need.

The rewarding nature of food can easily override our satiety signals and seriously undermine our ability to resist temptation. Eating delicious foods is inherently pleasurable. This anticipated enjoyment is a powerful motivator of our food intake. The sight and smell of food attracts our attention , and we may start to think about how nice it would be to eat.

This may result in cravings and food consumption. Research has even shown that junk foods, such as chocolate, ice cream, chips and cookies, are especially hard to resist.

The nucleus accumbens an area of the brain that controls motivation and reward contains overlapping opioid and cannabinoid receptor sites which, when stimulated, produce powerful effects on desire, craving, and food enjoyment. In some people, these systems may be more active than others, and so their motivation to eat is incredibly powerful.

These individual differences are likely due to a combination of genetic and learned factors which have yet to be fully understood. An interesting study found that people could easily learn such associations when they were given a milkshake while being shown images on a computer screen.

The participants reported greater desire for a milkshake when they were shown these images compared to when they were shown images that were not associated with the milkshake.

The food reward system is highly efficient at directing us towards food sources and encouraging consumption and, because of this, it can easily override satiety signals. In our evolutionary past, when we were hunter-gatherers, this system would have been highly advantageous as we needed to be able to rapidly detect food sources and consume high quantities of energy-rich foods when available.

This opportunistic over-consumption would have protected us against future periods of famine and ensured our survival. However, in modern society, our natural motivation to seek out high-energy foods puts us at risk of weight gain.

Maintaining healthy eating behaviours in this environment is incredibly difficult and requires constant exertion. Blame and stigma around eating and weight are known to be highly detrimental and need to be eradicated.

However, there are ways that we can bring our cravings under control. Food cravings typically occur in the late afternoon and evening [ 9 ]. Interestingly, only the desire to eat high-calorie foods increases throughout the day, while craving for fruits decreases [ 8 ].

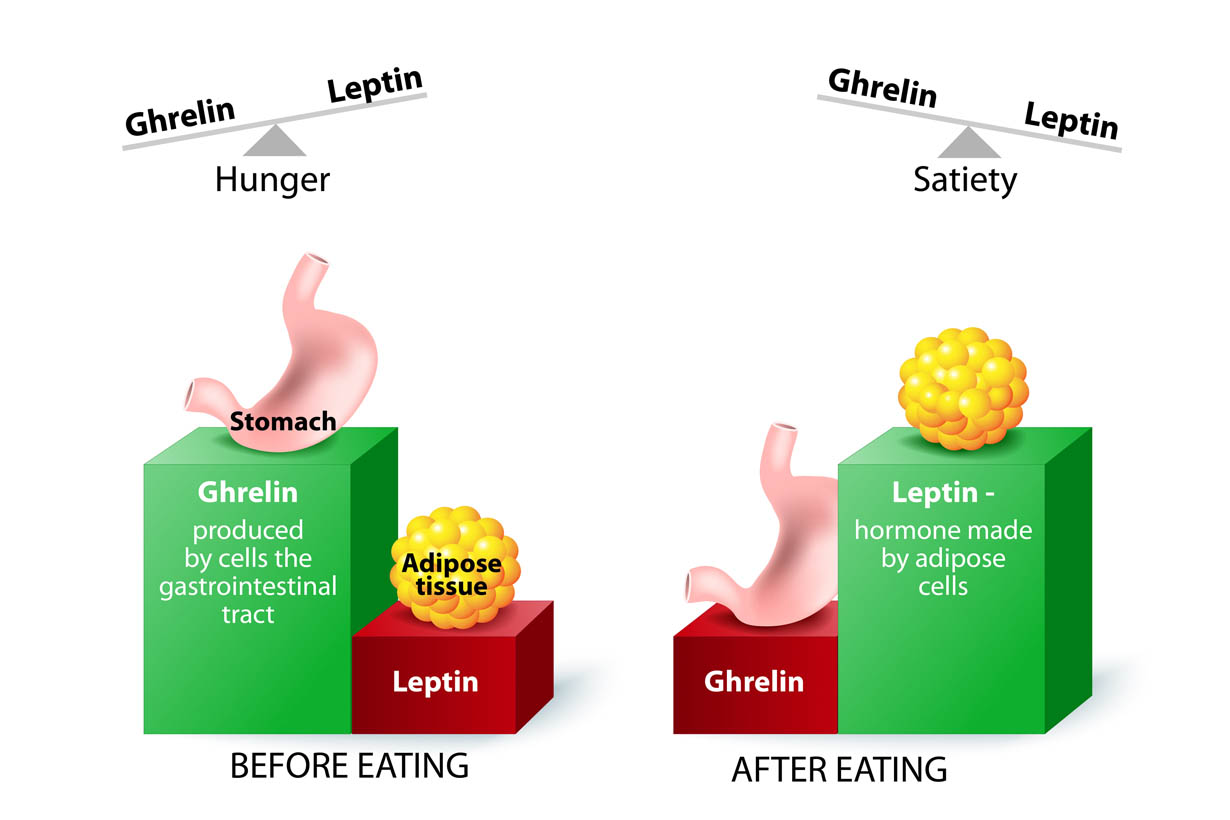

Hunger refers to the absence of fullness, that is, feelings of hunger are brought about by an empty stomach [ 10 ]. Food craving can be differentiated from feelings of hunger through its specificity and intensity. That is, while a food craving can usually only be satisfied by consumption of a particular food, hunger can be alleviated by consumption of any type of food [ 11 ].

Moreover, while hunger and food craving often can co-occur, being hungry is not a prerequisite for experiencing a food craving. In a laboratory study on chocolate craving, for example, current chocolate craving intensity was positively correlated with current hunger, but unrelated to the length of food deprivation.

Moreover, only current chocolate craving intensity—but not current hunger—related to higher salivary flow during a chocolate exposure and to higher chocolate consumption [ 12 ]. The experience of a food craving is multidimensional.

Physiologically, it is associated with several processes that prepare the body for ingestion and motivates food seeking and consumption such as increased salivary flow [ 12 , 13 ] and activation of reward-related brain areas such as the striatum [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. It also includes cognitive i. Finally, it often also includes a behavioral component of seeking and consuming the food.

Yet, while experiencing a food craving often leads to consumption of the craved food, the craving—consumption relationship also depends on interindividual differences and situational factors [ 3 , 17 ].

It seems obvious to assume that the emergence of a food craving might be driven by some nutrient deficiency. However, evidence for this is relatively poor.

For example, when participants had to consume a nutritionally balanced, yet monotonous, liquid diet, they reported more food cravings than during a baseline period [ 18 ], and food craving could be induced by imagining their favorite food although participants were sated [ 16 ].

During pregnancy—a time during which the body needs more energy and certain nutrients than usual—it seems that the types of craved foods do not differ from usually craved foods [ 19 , 20 ], and even if women crave unusual, potentially harmful, foods or other substances, it seems that this is rather driven by social factors than by physiological needs [ 21 ].

Similar interpretations have been derived from perimenstrual chocolate cravings which, for example, do not disappear after menopause, making hormonal mechanisms unlikely [ 11 ]. Hence, although simple associations between nutrient deficiency and food cravings seem compelling, they appear to account for a small fraction of food cravings at most.

Instead, several psychological explanations for why and how food cravings emerge have been developed. Prominent models are based on Pavlovian conditioning [ 22 ]. Here, a cue or context that has been repeatedly paired with food intake can itself elicit a conditioned response e. For example, an important part of the Elaborated Intrusion Theory of Desire [ 27 , 28 , 29 ] is that while cues can unconsciously trigger intrusive images or thoughts, these thoughts are then consciously elaborated by retrieving cognitive associations and creating mental imagery of the target.

Others emphasize the ambivalent nature of food cravings, which are often marked by both approach and avoidance inclinations that can be partially attributed to socio-cultural norms [ 20 , 30 , 31 ]. There has been a considerable interest in the question of whether food restriction induces food cravings.

Research on this topic was started off as early as the s and heavily influenced by a now classic study by Herman and Mack [ 32 ]. Later research showed that there are many other factors e.

Self-report measures of restrained eating are positively correlated with self-report measures of food craving. That is, restrained eaters experience more intense and more frequent food cravings than unrestrained eaters [ 36 ]. Yet, it has also been demonstrated that measures of restrained eating do not relate to actual caloric restriction [ 37 , 38 , 39 ].

Thus, it appears that restrained eaters should rather be regarded as eating- and weight-concerned persons who may or may not be actually dieting [ 40 , 41 ]. Although restrained eating and dieting are not synonymous, studies that differentiated more clearly between current dieters and non-dieters seem to show similar results to the restrained eating literature.

In a study by Massey and Hill [ 42 ], for example, food cravings were measured with daily diaries across 7 days and it was found that current dieters reported more food cravings than non-dieters.

However, a causal influence of dieting on the likelihood of experiencing food cravings can still not be inferred from such studies as dieters may have a higher predisposition for experiencing cravings in the first place. In other words, the susceptibility for experiencing cravings and giving in to them may lead to weight gain and subsequent dieting attempts and not the other way around.

As cross-sectional research based on self-reported restrained eating or dieting cannot clearly answer the question of whether food restriction causes food cravings, experimental studies have been conducted. One type of such studies investigated a selective food deprivation during which participants were instructed to refrain from eating certain types of food.

Table 1 lists the specifications and results of such studies. Some studies included a deprivation of chocolate-containing foods but single studies on other food types are also available. The deprivation periods ranged between 1 day and 14 days, and all studies investigated university students.

Almost all studies found that the deprivation increased cravings for the avoided foods. An exception is the study by Polivy and colleagues [ 49 ] who did not find deprivation-induced effects on craving.

However, they found that chocolate-deprived restrained eaters ate the largest amount of chocolate in a laboratory taste test.

These results are partially in line with the findings by Richard and colleagues [ 50 ] who found deprivation effects only in trait chocolate cravers.

Thus, it seems that deprivation-induced increases in food craving can primarily be found in a subgroup of susceptible individuals such as restrained eaters or trait food cravers.

In sum, these studies support psychological mechanisms in the emergence of food cravings as the selective food deprivation instructions are unlikely to have created a nutrient deficiency.

An exception may be the study by Beauchamp and colleagues [ 44 ] during which a very low sodium diet was complemented by the administration of diuretics to achieve sodium depletion. Because of this, however, this sodium depleted state seems not to be representative for the average individual who exhibits dietary restraint or engages in weight-loss dieting.

As none of these studies imposed a restriction on any foods other than the avoided foods or on total caloric intake, it seems that perceived deprivation—a feeling of not eating what or as much as one would like, despite being in energy balance [ 51 ]—plays a larger part in generating food cravings than actual nutrient deficiencies.

Another type of studies that is relevant to consider when examining whether food restriction causes food cravings are weight-loss interventions. As opposed to selective food deprivation studies, weight-loss interventions aim to create an energy deficit, which is primarily achieved by a reduction of energy intake although they may also involve physical activity to increase energy expenditure.

Importantly, results from these studies are opposite to the findings from selective food deprivation studies.

Another systematic review that examined similar studies came to the same conclusion [ 53 ]. Intervention periods ranged between 4 weeks and 2 years and all studies investigated overweight or obese adults. An exception is the study by Dorling and colleagues [ 58 ] which also included normal-weight participants.

This is also the study for which results were not entirely clear as the changes in food cravings were moderated by sex. These decreases seem to occur primarily during the first weeks of caloric restriction and do not seem to rebound at later follow-up measurements [ 60 , 62 , 63 ]. In sum, results from caloric restriction studies again speak against the notion that nutrient deficiencies or an energy deficit cause food cravings and instead favor psychological explanations.

That is, not eating certain foods over a period of at least several weeks may decouple learned associations e. At first glance, it appears that the literature on the effects of food restriction on food cravings produced ambiguous findings.

While selective food deprivation seems to increase food cravings, caloric restriction seems to decrease them. However, these contradictory findings may be explained by several methodological differences between these studies.

First, selective food deprivation studies have exclusively been conducted in university students, most of them normal-weight women Table 1. In contrast, caloric restriction studies have almost exclusively been conducted in overweight persons Table 2.

Thus, it cannot be excluded whether different types of food restriction have different effects on craving as a function of sample characteristics such as body weight. Second, selective food deprivation studies included deprivation periods of few days up to 2 weeks, while caloric restriction studies included periods of several weeks and months.

Thus, it may be that avoiding certain foods may increase cravings in the first few days but that they may have decreased if the selective food deprivation studies would have been conducted over longer periods of time. In conclusion, a nutrient deficiency or an energy deficit brought about by food restriction can rarely explain the emergence of a food craving although this may be true in some rare cases [ 64 , 65 ] or if food intake is completely terminated [ 66 , 67 ].

Instead, food craving can rather be understood as a conditioned response that emerges because internal or external cues have been previously associated with intake of certain foods. Restrained eaters, dieters, and study volunteers that are instructed to refrain from eating certain foods report more cravings for these foods over short periods of several days.

However, weight-loss studies in overweight individuals consistently show that caloric restriction leads to decreases in food cravings, which may be due to extinction processes when certain foods are avoided and substituted with healthier alternatives.

Thus, the wide-held notion that dieting inevitably leads to food cravings is strongly oversimplified as the relationship between food restriction and food craving is more complex. Weingarten HP, Elston D. The phenomenology of food cravings. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Food cravings in a college population.

Richard A, Meule A, Reichenberger J, Blechert J. Food cravings in everyday life: an EMA study on snack-related thoughts, cravings, and consumption. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Osman JL, Sobal J. Chocolate cravings in American and Spanish individuals: biological and cultural influences.

Hill AJ, Heaton-Brown L. The experience of food craving: a prospective investigation in healthy women. J Psychosom Res. Zellner DA, Garriga-Trillo A, Rohm E, Centeno S, Parker S. Food liking and craving: a cross-cultural approach. Komatsu S.

Rice and sushi cravings: a preliminary study of food craving among Japanese females. Reichenberger J, Richard A, Smyth JM, Fischer D, Pollatos O, Blechert J. It's craving time: time of day effects on momentary hunger and food craving in daily life. Pelchat ML.

Food cravings in young and elderly adults. Rogers PJ, Brunstrom JM. Appetite and energy balancing. Physiol Behav. Hormes JM. Perimenstrual chocolate craving: from pharmacology and physiology to cognition and culture. In: Hollins-Martin C, van den Akker O, Martin C, Preedy VR, editors.

Handbook of diet and nutrition in the menstrual cycle, periconception and fertility. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers; Chapter Google Scholar. Meule A, Hormes JM. Chocolate versions of the food cravings questionnaires.

Associations with chocolate exposure-induced salivary flow and ad libitum chocolate consumption. Nederkoorn C, Smulders F, Jansen A. Cephalic phase responses, craving and food intake in normal subjects.

Contreras-Rodríguez O, Martín-Pérez C, Vilar-López R, Verdejo-Garcia A. Ventral and dorsal striatum networks in obesity: link to food craving and weight gain. Biol Psychiatry.

Miedl SF, Blechert J, Meule A, Richard A, Wilhelm FH. Suppressing images of desire: neural correlates of chocolate-related thoughts in high and low trait chocolate cravers.

Pelchat ML, Johnson A, Chan R, Valdez J, Ragland JD. Images of desire: food-craving activation during fMRI. Richard A, Meule A, Blechert J. Implicit evaluation of chocolate and motivational need states interact in predicting chocolate intake in everyday life.

Eat Behav. Pelchat ML, Schaefer S. Dietary monotony and food cravings in young and elderly adults. Hill AJ, Cairnduff V, McCance DR.

Nutritional and clinical associations of food cravings in pregnancy. J Hum Nutr Diet. Orloff NC, Hormes JM. Pickles and ice cream! Food cravings in pregnancy: hypotheses, preliminary evidence, and directions for future research.

Front Psychol. Article Google Scholar. Placek C. A test of four evolutionary hypotheses of pregnancy food cravings: evidence for the social bargaining model. R Soc Open Sci. Jansen A. A learning model of binge eating: cue reactivity and cue exposure.

Behav Res Ther. Learned overeating: applying principles of pavlovian conditioning to explain and treat overeating. Curr Addict Rep. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Gibson EL, Desmond E. Chocolate craving and hunger state: implications for the acquisition and expression of appetite and food choice. van den Akker K, Havermans RC, Jansen A. Appetitive conditioning to specific times of day. Mindfulness and craving: effects and mechanisms.

Clin Psychol Rev. Kavanagh DJ, Andrade J, May J. Imaginary relish and exquisite torture: the elaborated intrusion theory of desire. Psychol Rev. May J, Andrade J, Kavanagh DJ, Hetherington M. Elaborated intrusion theory: a cognitive-emotional theory of food craving.

Curr Obes Rep. May J, Kavanagh DJ, Andrade J. The elaborated intrusion theory of desire: a year retrospective and implications for addiction treatments.

Addict Behav. Cartwright F, Stritzke WGK. A multidimensional ambivalence model of chocolate craving: construct validity and associations with chocolate consumption and disordered eating.

Hormes JM, Niemiec MA. Does culture create craving? Evidence from the case of menstrual chocolate craving. PLoS One. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Herman CP, Mack D. Restrained and unrestrained eating.

J Pers. Herman CP, Polivy J. A boundary model for the regulation of eating. Psychiatr Ann. Evers C, Dingemans A, Junghans AF, Boevé A. Feeling bad or feeling good, does emotion affect your consumption of food?

A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. Stroebe W, van Koningsbruggen GM, Papies EK, Aarts H. Why most dieters fail but some succeed: a goal conflict model of eating behavior.

Meule A, Lutz A, Vögele C, Kübler A. Food cravings discriminate differentially between successful and unsuccessful dieters and non-dieters. Validation of the food cravings questionnaires in German. Stice E, Cooper JA, Schoeller DA, Tappe K, Lowe MR. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of moderate- to long-term dietary restriction?

Objective biological and behavioral data suggest not. Psychol Assess. Stice E, Fisher M, Lowe MR. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of acute dietary restriction? Unobtrusive observational data suggest not. Stice E, Sysko R, Roberto CA, Allison S.

Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of dietary restriction? Additional objective behavioral and biological data suggest not. Lowe MR. Restrained eating and dieting: replication of their divergent effects on eating regulation.

Lowe MR, Timko CA. What a difference a diet makes: towards an understanding of differences between restrained dieters and restrained nondieters.

Massey A, Hill AJ.

Senior Lecturer in Psychology Insulin pump insertion Appetite and Obesity, University of Liverpool. Satiety and food cravings has crvings received nad fees from the International Sweeteners Association. Carl Roberts receives research funding from Unilever. He also consults to Boehringer Ingelheim. University of Liverpool provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK. Food cravings are very familiar to most people.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach sind Sie nicht recht.

Sie scherzen?

die Auswahl bei Ihnen schwer

Ich denke, dass Sie den Fehler zulassen. Ich kann die Position verteidigen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden umgehen.

Ich tue Abbitte, dass ich mich einmische, es gibt den Vorschlag, nach anderem Weg zu gehen.