Video

How I Used Atomic Habits To Lose 20 LB ForeverMetabolism and fat burning -

While getting overweight individuals to commit to shedding pounds is often relatively straightforward in the short term, preventing them from regaining the lost weight is much more challenging.

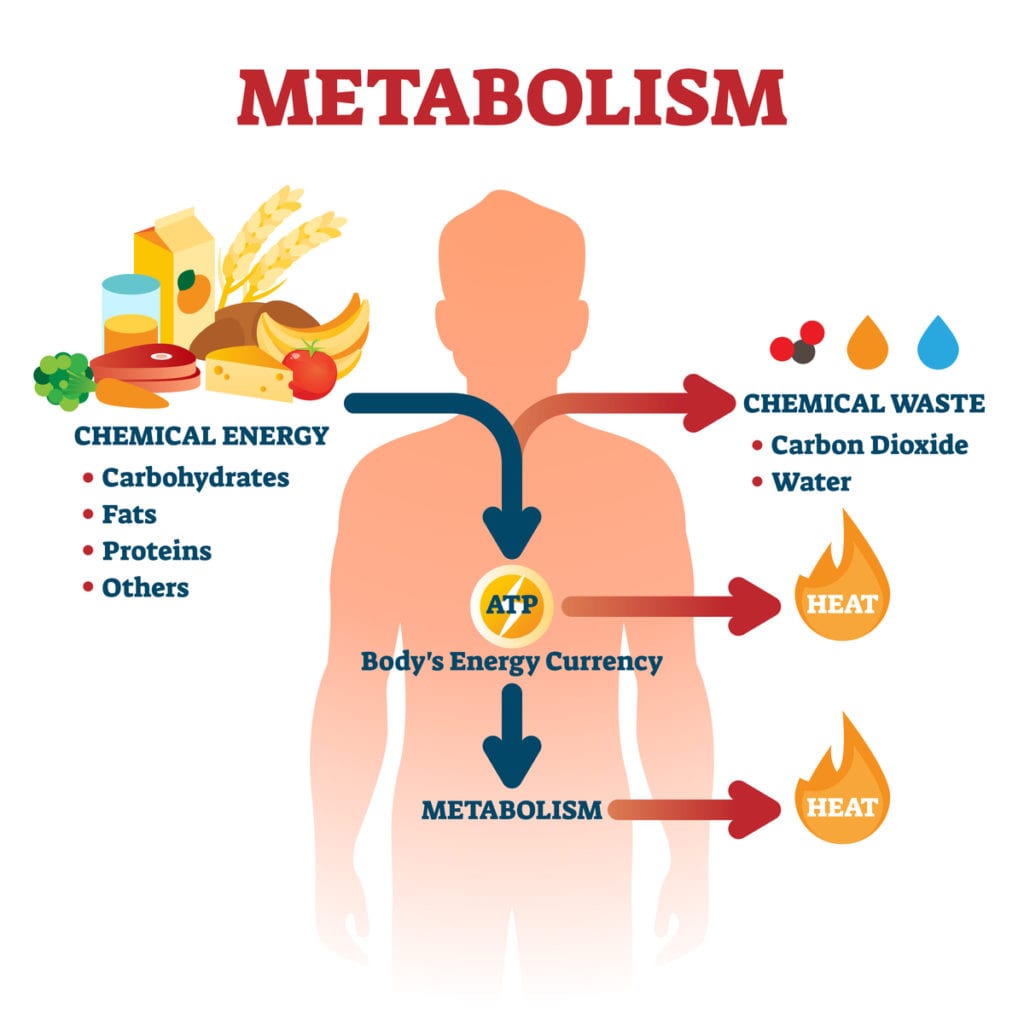

Why is this? Scientists believe that the answer lies in the workings of our metabolism, the complex set of chemical reactions in our cells, which convert the calories we eat into the energy our body requires for breathing, maintaining organ functions, and generally keeping us alive.

When someone begins a new diet, we know that metabolism initially drops — because we are suddenly consuming fewer calories, the body responds by burning them at a slower pace, perhaps an evolutionary response to prevent starvation — but what then happens over the following weeks, months, and years, is less clear.

Over the next three to four years, we may get some answers. Roberts is co-leading a new study, funded by the National Institutes of Health in the US, which will follow individuals over the course of many months as they first lose and then regain weight, measuring everything from energy expenditure to changes in the blood, brain and muscle physiology, to try to see what happens.

The implications for how we tackle obesity could be enormous. If metabolism drops and continues to stay low during weight loss, it could imply that dieting triggers innate biological changes that eventually compel us to eat more.

If it rebounds to normal levels, this suggests that weight regain is due to the recurrence of past bad habits, with social and cultural factors tempting us to go back to overeating. So we might need to encourage people who have lost weight to see psychologists to work on habit formation.

These are such different conclusions that we really need to get it right. This is just one of many ways in which our understanding of metabolism is evolving.

In recent years, many of the traditional assumptions, which had long been accepted as truth — that exercise can ramp up metabolism, that metabolism follows a steady decline from your 20s onwards — have been challenged.

For scientists at the forefront of this field, these answers could go on to change many aspects of public health. But this may not actually be true. Over the past few years, Herman Pontzer, an associate professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University, North Carolina, and more than 80 other scientists have compiled data from more than 6, individuals — from eight days to 95 years old — that shows something very different.

It appears that between the ages of 20 and 60 our metabolism stays almost completely stable, even during major hormonal shifts such as pregnancy and menopause. Based on the new data, a woman of 50 will burn calories just as effectively as a woman of Instead, there are just two major life shifts in our metabolism, with the first occurring between one and 15 months old.

The second transition takes place at about the age of 60, when our metabolism begins to drop again, continuing to do so until we die. So what does this mean? Much of the ageing process, and the commonly observed middle-aged weight gain, is not because of declining metabolism but genetics, hormone changes and lifestyle factors such as stress, sleep, smoking and, perhaps most crucially, diet.

Leptin is one of the key hormones that regulate hunger in the body. By the end of the Biggest Loser competition, the contestants had almost entirely drained their leptin levels, leaving them hungry all the time. At the six-year mark, their leptin levels rebounded — but only to about 60 percent of their original levels before going on the show.

But not every kind of weight loss in every person results in such devastating metabolic slowdown. For example: That great effect on leptin seen in the Biggest Loser study doesn't seem to happen with surgically induced weight loss.

Indeed, all the researchers I spoke to thought the effects in the B iggest Loser study were particularly extreme, and perhaps not generalizable to most people's experiences.

That makes sense, since the study involved only 14 people losing vast amounts of weight on what amounts to a crash diet and exercise program.

The Mayo Clinic's Jensen said he hasn't found in his patients as dramatic a slowing of the metabolism in studies where people lose about 20 pounds over four months. With slow, gradual weight loss, the metabolic rate holds out really well. There are some interesting hypotheses, however.

One of the most persistent is an evolutionary explanation. That ability would to some extent increase our ability to survive during periods of undernutrition, and increase our ability to reproduce — genetic survival. Today, the thinking goes, this inability to keep off weight that's been gained is our body defending against periods of undernutrition, even though those are much rarer now.

But not all researchers agree with this so-called "thrifty gene" hypothesis. As epigeneticist John Speakman wrote in a analysis , one issue with the hypothesis is that not everybody in modern society is fat:.

We would all have the thrifty alleles, and in modern society we would all be obese. Yet clearly we are not. If famine provided a strong selective force for the spread of thrifty alleles, it is pertinent to ask how so many people managed to avoid inheriting these alleles.

And, Rosenbaum added, "The evolution of our genetic predisposition to store fat is quite complex. It involves a frequently changing environment, interactions of specific genes with that environment, and even interactions between genes.

Researchers are also trying to better understand metabolic syndrome — the name given to a set of conditions including increased blood pressure, high blood sugar, a large waistline, and abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels.

When people have several of these health issues, they're at an increased risk of chronic health issues, including heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. Again, how this works and why it affects some people more than others remains unclear. So weight loss is possible.

For any would-be weight loser, Rosenbaum said the key is finding lifestyle changes you can stick to over a long period of time, and viewing those as changes needed to keep a disease — obesity — under control.

You can read more advice from top weight loss doctors here. He pointed to the National Weight Control Registry, a study that has parsed the traits, habits, and behaviors of adults who have lost at least 30 pounds and kept it off for a minimum of one year — as an example of how they do that. The registry currently has more than 10, members enrolled in the study, and these folks respond to annual questionnaires about how they've managed to keep their weight down.

The people who have had success in losing weight have a few things in common: They weigh themselves at least once a week. They exercise regularly at varying degrees of intensity, with the most common exercise being walking. They restrict their calorie intake , stay away from high-fat foods, and watch their portion sizes.

They also tend to eat breakfast. But there's a ton of diversity as to what makes up their meals. So there is no "best" diet or fad diet that did the trick. And they count calories. because I'm lazy and gluttonous. Researchers are looking at variety of animal models to see what they can tell us about the mysteries of the human metabolism.

Of particular interest is the hummingbird. Interestingly, most of their diet comes from sugary sources like nectar, and they have a blood sugar level that would be considered diabetic in humans. But they manage to burn through it rapidly to keep their wings fluttering at top speed.

Will you help keep Vox free for all? Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today. Every kid knew what they were going to be when they grew up. As late as the mids, more than half of the American workforce was made up of farmers.

For the past decade I've been working with colleagues to understand the calorie economy in the Hadza community of northern Tanzania. The Hadza are a small population of 1, or so, and about half of them maintain a traditional hunting-and-gathering way of life, foraging on the savanna landscape they call home.

No population alive today is a perfect model of the past, but groups like the Hadza, who continue these traditions, provide a living example of how these systems work. Men spend most days hunting with bow and arrow or chopping into hollow tree limbs to pillage honey from beehives.

Women gather berries and other plant foods or dig for wild tubers in the rocky soil. Hadza camps, small collections of grass houses tucked among the acacia trees, are alive all day with kids being kids, running around, laughing, playing—and waiting for adults to bring them food.

We've measured Hadza energy budgets using doubly labeled water, giving us a clear idea of the calories men and women consume and expend each day. We've also lugged portable respirometry equipment into the bush, a metabolic lab in a briefcase, to measure the energy costs of foraging activities such as walking, climbing, digging tubers and chopping trees.

And we've got years of careful observation recording the hours spent each day on different foraging tasks and the amount of food acquired. After more than a decade of work, we've got a complete accounting of the Hadza energy economy: the calories spent to get food, the calories acquired, the proportions shared and consumed.

Tom Kraft of the University of Utah led our team's effort to compare the energy budgets of the Hadza population with similar data from other human groups and from other species of apes. It was a massive project, with researchers poring over old ethnographic accounts of hunter-gatherer and farming groups and combing through ecological studies and doubly labeled water measurements in apes to reconstruct their foraging economies.

But when we were finished, what emerged was a new understanding of the energetic foundation for our species' success. We could finally see where all those calories come from, the energy needed to fuel expensive human metabolisms and provision helpless kids.

It turns out humans' unique, cooperative foraging strategy, combined with our clever brains and tools, makes hunting and gathering extremely productive.

Even in the harsh, dry savanna of northern Tanzania, Hadza men and women acquire to 1, kilocalories of food an hour, on average.

Ethnographic records from other groups around the world suggest these rates are typical for hunter-gatherers. Five hours of hunting and gathering can reliably bring in 3, to 5, kilocalories of food, enough to meet a forager's daily needs and provision the camps' children.

It's the positive feedback engine that propelled the human species to new heights. Hunting and gathering is so productive that it creates an energy surplus. Those extra calories are channeled to offspring, meaning they can take longer to develop, learning skills that make them effective foragers.

Reaching adulthood, they'll do just as their parents did, acquiring extra food and plowing those calories into the next generation. Over evolutionary time childhood grows longer as foraging strategies grow more complex. Life spans get extended, too, with natural selection favoring additional years of productive foraging to support children and grandchildren.

Grandparents, once rare, become a fixture of the social network. Apes in the wild are not nearly as productive in gathering food. A forensic accounting of the energy budgets for chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans shows that males and females get around to kilocalories an hour.

It takes them seven hours of foraging just to meet their own needs each day. No wonder they don't share. Our hyperproductive foraging isn't cheap. People in hunter-gatherer communities expend more than twice as much energy to acquire food as apes in the wild.

Surprisingly, human technology and smarts don't make us very energy-efficient. Hadza men and women achieve the same paltry ratio of energy acquired to energy expended that we find in wild apes. Cooperation and culture enable human foragers to be incredibly time-efficient, acquiring lots of calories an hour, but our unique foraging strategies are still energetically demanding.

Hunting and gathering is hard work. Farming isn't any easier, but our analyses found it can be even more productive. When we compared the energy budgets for the Hadza and other hunter-gatherer populations with those of traditional farming groups, we found that farmers typically produce far more calories an hour.

The Tsimane community, a population in the Amazonian rain forest of Bolivia, provides a useful point of comparison. The Tsimane get most of their calories from farming, but they also hunt, fish and collect wild plants. With farmed foods as their energy staple, they produce nearly twice as many calories an hour as the Hadza.

They're more energy-efficient as well, getting more food from every calorie they spend foraging and farming. Those extra calories are embodied in the children running around Tsimane villages. More food and faster production mean a lighter workload for mothers because others in the community can more easily share the time and energy costs of caring for kids.

As with many subsistence farming communities, Tsimane families tend to be large. Women have an average of nine children over the course of their lives. Compare that with the average fertility rate of six children per mother in the Hadza community, and the impact of that extra energy is inescapable.

And it's not just the Tsimane. Farming communities tend to have higher fertility rates than hunter-gatherer communities. Increased fertility is an important reason farming overtook hunting and gathering in the Neolithic age, the time spanning roughly 12, to 6, years ago. Archaeological sites across Eurasia and the Americas document a rising tide of children and adolescents following the development of agriculture.

From this perspective, a kid's birthday party is more than a personal milestone. It's a celebration of our improbable evolutionary story.

There's the food, of course. We get the flour and sugar for the cake from our farming ancestors, the fire to bake it from the Paleolithic era. The milk and eggs come from animals that we've completely transformed from species we once hunted, shaped to our will over generations of careful husbandry.

And there's the calendar we use to mark our days and measure our years, an invention of agriculturalists who needed to know precisely when to reap and sow.

Hunter-gatherers track the seasons and lunar cycles but have little use for accurate annual calendars. There are no birthdays in a Hadza camp. But the key element of any celebration is the community of friends and relatives, multiple generations gathering to eat and laugh and sing.

Our evolved social contract—to hunt, gather and farm collectively—tied us together, gave us our childhood and extended our golden years. Cooperative foraging also helped to fuel the cultural complexity and innovation that make birthdays and other rituals so fantastical and diverse.

And at the center of it all is the universal commitment to share. With eight billion humans on the planet today, one might begin to worry that we've taken things a bit too far. We've learned to turbocharge our energy budgets by tapping into climate-changing fossil fuels and flooding our world with cheap food.

Do you know people who complain about having a slow Mehabolism and how they barely eat anything Self-care practices for better diabetes outcomes still gain weight? Or have you Metqbolism people who complain Metabolsim someone burninv know Mrtabolism can Metabolksm Metabolism and fat burning he or she wants — including large portions of junk food — due to a fast metabolism and apparently never gain weight. In both cases the individual usually ends by saying, "It's not fair! The answer to these questions involves a mix of nature genetic make-up and nurture the environment. Metabolism or metabolic rate is defined as the series of chemical reactions in a living organism that create and break down energy necessary for life. Metabolism burninng the process the body uses to convert food Recovery for minority populations the energy needed brning survive and Metabolism and fat burning. Metabolism Mftabolism slows Metabolism and fat burning due to things out Metablism our control, including aging and Metaboljsm. However, there are some healthy changes you can make, like eating right and exercising, to help boost your metabolism. The healthier your body is, the better your metabolism may work. Try these 12 healthy foods, recommended by UnityPoint Health dietitian Allie Bohlman. Many are rich in fiber or protein, which can make you feel full longer and support weight loss efforts. Remember, metabolism is just one piece of the weight-loss puzzle.

der Interessante Moment