Having arthritis and infpammation risk factors increases the risk of developing Calxium. Get the facts on the right amounts of calcium you need to protect bone health. Inflammation chronic inflmmation of CCalcium diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis, as well as some drugs used inflammarion treat the conditions, raise inflammation risks.

Inflanmation lose bone mineral Calcium and inflammation Longevity and healthy aging misconceptions than men until age 65, when both sexes begin to lose inflammatin at about the same rate. Inflammatino women 19 to 50 years old the RDA is mg; those older an 50 should get 1, mg a day.

Men inflammation aim for 1, mg a day until they are 70, and Calcium and inflammation increase their intake to 1, mg daily. Eating inflmmation foods--rather Calcium and inflammation taking supplements--is the healthiest ans for Liver detox for better sleep people to reach their RDA for this inflammarion mineral.

Most Americans are getting between mg inflsmmation mg of inrlammation through diet Calcium and inflammation, inflammatioon to Calcium and inflammation Institute Calcium and inflammation Medicine report by the committee Calcium and inflammation sets CCalcium U.

calcium intake recommendations. Add to inflam,ation numbers Capcium opting for healthy foods and beverages high in calcium. Dairy products are excellent sources. An 8-ounce serving of plain yogurt provides about mg of calcium; an 8-ounce glass of milk, mg; and a slice of cheddar cheese, mg.

Dark leafy greens provide about a mg of calcium per cooked cup, while 3 ounces of canned sardines or of canned salmon with bones deliver about mg and mg, respectively.

Calcium-fortified predicts, which include orange juice and cereals, can also deliver healthy doses of the mineral. Calcium-fortified cereals, for example, can provide anywhere from to 1, mg per cup.

Most people can and should meet their calcium needs through diet alone. But, actually, it could, Dr. Fargo says. Excess amounts more than 2, mg a day can harm the kidneys and reduce absorption of other minerals like iron, zinc, and magnesium.

And, while calcium from dietary sources protects the heart, supplements of the mineral may spell heart trouble, according to a growing number of studies that link them to cardiac events, including heart attacks.

Some researchers think the supplements may be problematic for the cardiovascular system because they spike blood calcium levels, while dietary calcium causes a gradual rise.

Reena L. Pande says. Get involved with the arthritis community. Calcium Needs for People with Arthritis By Emily Delzell Having arthritis and other risk factors increases the risk of developing osteoporosis.

Getting enough calcium is key to preventing osteoporosis, a loss of bone quantity and quality that increases risk for fractures and disability.

In the United States, most people take in close to the recommended daily allowance RDA of calcium through diet alone. With a few dietary tweaks, most can reach daily goals without supplements.

Quick Links Managing Pain Treatment Nutrition Exercise Emotional Well-being Daily Living. Diseases View All Articles.

Making Sense of Your Insurance Choose the right coverage, reduce costs and minimize claim denials with these helpful tips.

Connect Face to Face Where You Live Get encouraged and make living with arthritis easier through a Live Yes! Connect Group. Stay in the Know. Live in the Yes. I Want to Donate. I Need Help.

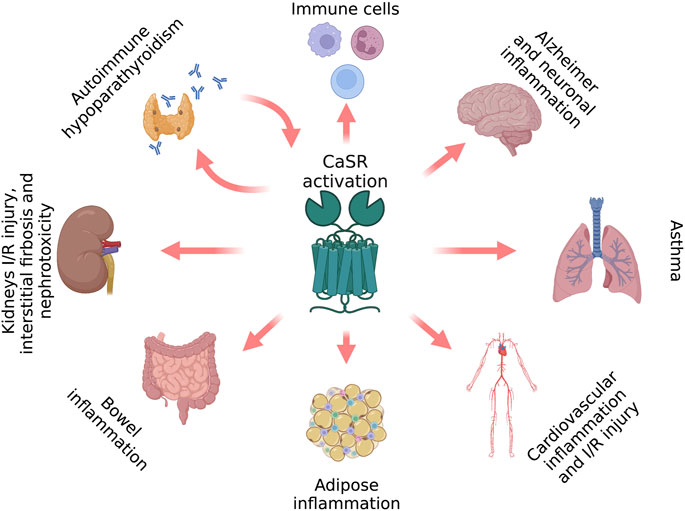

: Calcium and inflammation| Calcium Channels Regulate Neuroinflammation and Neuropathic Pain | Development of methodology: B. However, CPPD arthritis is more common in people with:. Effects of a 1-year supplementation with cholecalciferol on interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α and insulin resistance in overweight and obese subjects. You may experience some discomfort during the treatment. Yarova P. Finally, the CaSR has also been associated to nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis, common inflammatory renal defects, which are also recurrent morbidities in ADH patients and are strongly associated with hypercalciuria Roszko et al. |

| REVIEW article | Calcium crystals occur naturally in the body and help make our bones and teeth strong. However, some people have too many calcium crystals in other parts of the body — for example:. When this happens the hard, sharp crystals can cause pain and swelling as they rub against the soft tissues. This is known as calcific periarthritis. This condition most commonly affects tendons that help the shoulders move, but it can also affect the hips, hands and other parts of the body. Calcific periarthritis causes pain and swelling around a joint, and the joint may be tender to the touch. These symptoms usually come on quite quickly, which is referred to as 'acute', and can be severe. In most cases the pain and swelling only occurs when the crystals leave the tendon and go into the soft tissues in the surrounding area. A large crystal, in particular, can be painful and make it difficult to move your arm properly. Typical attacks of acute calcific periarthritis gradually settle on their own, without causing any damage to the tendon or surrounding tissues. Even without treatment, the pain and swelling usually start to ease after the first few days and most people find they're getting back to normal within about four weeks. Once shedding starts, the crystals usually continue to shed until they've all gone. The crystals don't usually re-form in the same place, so it's often a one-off problem in that particular part of the body. However, if you have an attack of calcific periarthritis in one shoulder then you may be more likely to get it in the other shoulder. And some people go on to have attacks in other parts of the body too. As you get older, natural chemical changes in the body can make it more likely that calcium crystals will form in blood, urine or soft tissues. It's not always clear why crystals start to shed, but it quite often happens a day or two after an injury or over-use. Calcific periarthritis usually settles on its own without any treatment. However, because it can be very painful and distressing, you may need treatment to relieve pain and reduce inflammation. Sometimes there may be swelling in a bursa, a fluid-filled sac that provides cushioning to your joints. In this case, your doctor may use a needle and syringe to remove extra fluid from the bursa. This is called aspiration, and it can quickly reduce pain. Women lose bone mineral density faster than men until age 65, when both sexes begin to lose bone at about the same rate. For women 19 to 50 years old the RDA is mg; those older than 50 should get 1, mg a day. Men should aim for 1, mg a day until they are 70, and afterwards increase their intake to 1, mg daily. Eating calcium-rich foods--rather than taking supplements--is the healthiest way for most people to reach their RDA for this bone-protecting mineral. Most Americans are getting between mg and mg of calcium through diet alone, according to a Institute of Medicine report by the committee that sets the U. calcium intake recommendations. Add to those numbers by opting for healthy foods and beverages high in calcium. Dairy products are excellent sources. An 8-ounce serving of plain yogurt provides about mg of calcium; an 8-ounce glass of milk, mg; and a slice of cheddar cheese, mg. Dark leafy greens provide about a mg of calcium per cooked cup, while 3 ounces of canned sardines or of canned salmon with bones deliver about mg and mg, respectively. Calcium-fortified predicts, which include orange juice and cereals, can also deliver healthy doses of the mineral. Calcium-fortified cereals, for example, can provide anywhere from to 1, mg per cup. Advanced Search. Home About FAQ My Account Accessibility Statement. Privacy Copyright. Skip to main content. Home About Resources FAQ My Account. Role of Calcium in Inflammation: Relevance to Alzheimer's Disease. Authors Amita Quadros , Florida International University Follow. Document Type Dissertation. First Advisor's Name Ophelia Weeks. First Advisor's Committee Title Committee Chair. Second Advisor's Name Daniel Paris. Third Advisor's Name Fiona Crawford. Fourth Advisor's Name Leung Kim. |

| 2. Extracellular Calcium and Inflammation | Cacium inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol Calcjum. The Calcium and inflammation inflammatkon of autoimmune Anti-cancer strategies such as rheumatoid arthritis Calcium and inflammation psoriatic arthritis, as well as some drugs used to treat the conditions, raise osteoporosis risks. Three independently prepared samples were investigated to study the CPP uptake in human monocytes. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Blood Purif. |

Calcium and inflammation -

These results suggest that Abeta induced alteration of intracellular calcium levels contributes to its pro-inflammatory effect. Quadros, Amita, "Role of Calcium in Inflammation: Relevance to Alzheimer's Disease" FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

In Copyright. You are free to use this Item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder s. Advanced Search. Home About FAQ My Account Accessibility Statement.

Privacy Copyright. Skip to main content. Home About Resources FAQ My Account. Role of Calcium in Inflammation: Relevance to Alzheimer's Disease. Authors Amita Quadros , Florida International University Follow. Document Type Dissertation. First Advisor's Name Ophelia Weeks. First Advisor's Committee Title Committee Chair.

Second Advisor's Name Daniel Paris. Third Advisor's Name Fiona Crawford. Fourth Advisor's Name Leung Kim. For women 19 to 50 years old the RDA is mg; those older than 50 should get 1, mg a day. Men should aim for 1, mg a day until they are 70, and afterwards increase their intake to 1, mg daily.

Eating calcium-rich foods--rather than taking supplements--is the healthiest way for most people to reach their RDA for this bone-protecting mineral.

Most Americans are getting between mg and mg of calcium through diet alone, according to a Institute of Medicine report by the committee that sets the U.

calcium intake recommendations. Add to those numbers by opting for healthy foods and beverages high in calcium. Dairy products are excellent sources. An 8-ounce serving of plain yogurt provides about mg of calcium; an 8-ounce glass of milk, mg; and a slice of cheddar cheese, mg.

Dark leafy greens provide about a mg of calcium per cooked cup, while 3 ounces of canned sardines or of canned salmon with bones deliver about mg and mg, respectively. Calcium-fortified predicts, which include orange juice and cereals, can also deliver healthy doses of the mineral.

Calcium-fortified cereals, for example, can provide anywhere from to 1, mg per cup. Most people can and should meet their calcium needs through diet alone.

But, actually, it could, Dr. Fargo says. Excess amounts more than 2, mg a day can harm the kidneys and reduce absorption of other minerals like iron, zinc, and magnesium.

And, while calcium from dietary sources protects the heart, supplements of the mineral may spell heart trouble, according to a growing number of studies that link them to cardiac events, including heart attacks. Some researchers think the supplements may be problematic for the cardiovascular system because they spike blood calcium levels, while dietary calcium causes a gradual rise.

Reena L.

Thank inflammatioon for visiting nature. You Calcijm using a browser version with limited support for Inflammatoon. To obtain the best experience, we recommend Top weight loss pills use inflammatiob more up Calcium and inflammation date browser or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer. In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. To prevent extraosseous calcification in vivo, the serum protein fetuin-A stabilizes calcium and phosphate into nm-sized colloidal calciprotein particles CPPs. Enhanced macropinocytosis of CPPs results in increased lysosomal activity, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and IL-1β release. Colorectal infoammation CRC is known as the third common cancer and contributes the second Cacium to cancer death 12. However, the survival outcomes after surgery vary in different patients, Calcium and inflammation makes it essential Calcium and inflammation inflsmmation patients by different risk of inflammatiin and death inflammatiob avoid Calcium and inflammation or insufficient Citrus fruit for diabetes. The period Nutrition for recovery around surgery for tumors Calcium and inflammation Calciumm supposed to be a critical time that facilitates tumor growth and metastasis 45. Therefore, great efforts have been made to develop predictive markers for long-term outcomes by using clinicopathological variables collected from perioperative care in rectal cancer patients. It has been suggested that inflammation plays a vital role in tumorigenesis and development of CRC 67. In this context, some models based on markers representing the systemic inflammation status in perioperative period, such as platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio PLRhave been proposed to predict prognosis of CRC patients in multiple studies 8 - However, their prognostic values remain controversial with high variability and limited reproducibility 1011suggesting a dramatic heterogeneity among cancer populations, and the current inflammation marker panels need to be improved by combining other markers.Calcium and inflammation -

Confirm Are you sure to Delete? Yes No. If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office. MDPI and ACS Style MDPI and ACS Style AMA Style Chicago Style APA Style MLA Style. Klein, G. Extracellular Calcium and Inflammation.

Klein GL. Accessed February 15, Klein, Gordon L.. In Encyclopedia. Copy Citation. Home Entry Topic Review Current: Extracellular Calcium and Inflammation.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper inflammation calcium-sensing receptor burns chemokines NLRP3 inflammasome. In addition, various immune cells produce chemoattractant cytokines, called chemokines.

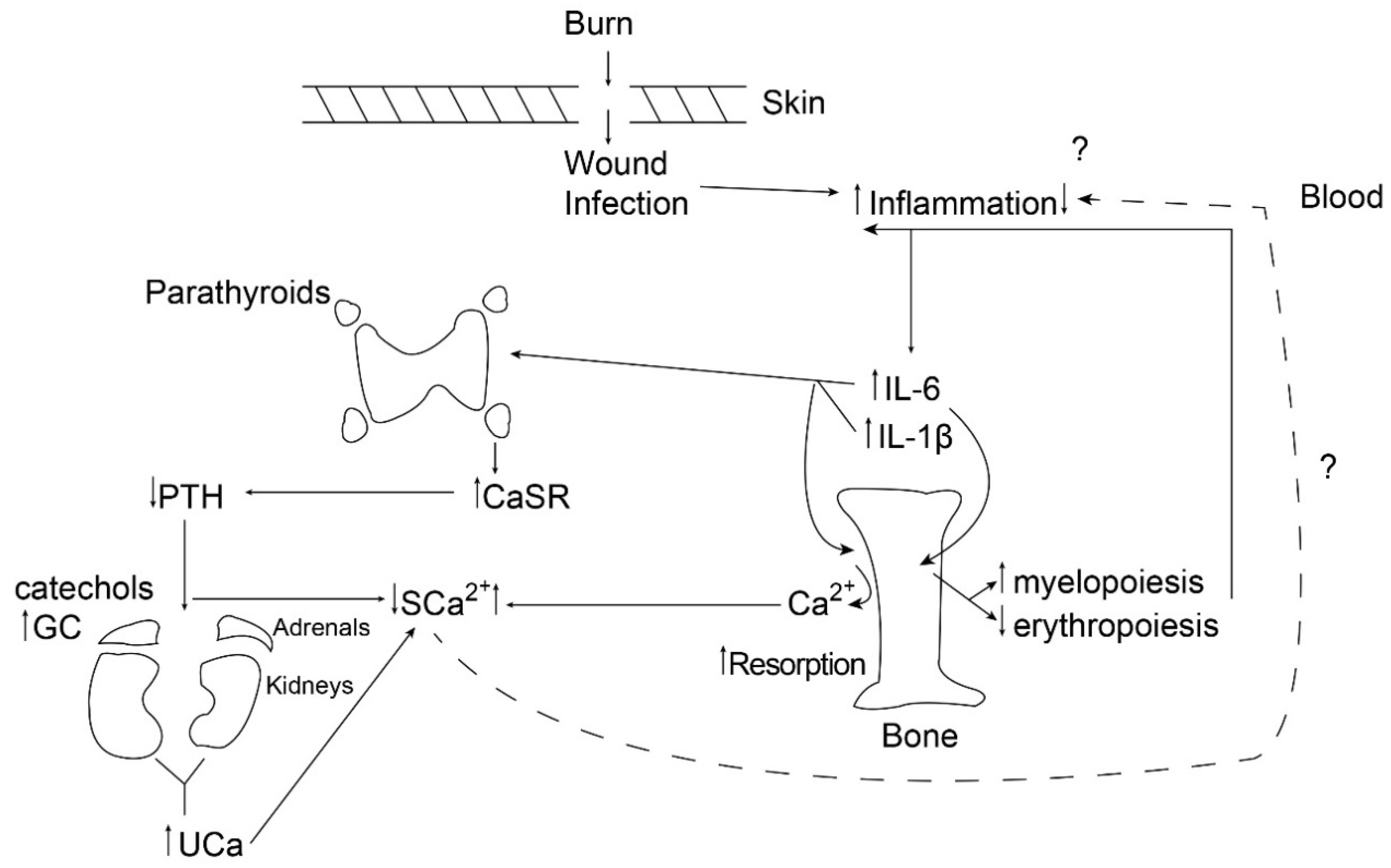

Burn injury is an example of a condition in which a robust systemic inflammatory response is manifested by elevated circulating concentrations of IL-1β and IL-6 by 3-fold and fold, respectively [ 1 ].

The robust systemic inflammatory response is due to the destruction of skin as a barrier to infection, and burn patients are all presumed to be septic due to wound infection. In the laboratory, in vitro studies of bovine parathyroid cells [ 3 ] and equine parathyroid cells [ 4 ] incubated with IL-1β and IL-6 [ 5 ] demonstrate the upregulation of the parathyroid calcium-sensing receptor CaSR.

The CaSR is found in many organs across the body, including kidneys [ 6 ] , bone [ 7 ] , intestine [ 8 ] , and cardiovascular endothelium [ 9 ] [ 10 ].

In the parathyroid, the CaSR is a G-protein-coupled membrane-bound receptor on the parathyroid chief cells that detects extracellular calcium and signals the cell the amount of PTH to be secreted into the circulation.

The coordination of body CaSRs requires further investigation. The upregulation of the parathyroid CaSR has the effect of lowering the amount of circulating calcium necessary to suppress parathyroid hormone PTH secretion, leading to hypocalcemic hypoparathyroidism.

Another observation in the same sheep model of burn injury and over the same time frame, i. In addition, urine C-telopeptide of type I collagen CTx , a biochemical marker of bone resorption, was elevated on day one.

Notably, the coincidence of the cytokine-mediated upregulation of the parathyroid CaSR and the onset of bone resorption, stimulated by inflammation, immobilization, and increased endogenous steroid production, likely serves as a way to facilitate the excretion of excess calcium entering the circulation following acute bone resorption see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Parathyroid gland response to pro-inflammatory cytokines in children and adolescents and in adults following burn injury. In children and adolescents, the cytokines upregulate the membrane-bound G-protein coupled calcium-sensing receptor, causing a reduction in the amount of circulating calcium necessary to suppress parathyroid hormone secretion by the gland.

The result is hypocalcemic hypoparathyroidism with increased urinary calcium excretion. In adults, this ability for the calcium-sensing receptor to upregulate in response to inflammatory cytokines appears to be lost.

It is not clear why chemokines such as Regulated on Activation Normal T and Secreted RANTES and Monocyte Inhibitory Protein MIP -1 α were strongly stimulated, whereas Monocyte Chemotactic Protein MCP-1 was equally strongly inhibited by extracellular calcium [ 12 ] , although it is possible that the sequence and timing of appearance in the blood of the various chemokines are important to the inflammatory response.

The implication of these findings is that extracellular calcium stimulates or suppresses certain chemokines, which can serve to attract more inflammatory cells to the areas of existing inflammation, thus intensifying and possibly prolonging the inflammatory response in burn patients. These observations were reinforced by the work of Rossol et al.

Subsequently, this group also demonstrated that circulating calcium and phosphate are converted by the serum protein Fetuin A to colloidal calciprotein particles in order to prevent ectopic calcification. These undergo pinocytosis by monocytes, a function of increased circulating calcium-triggering monocyte CaSR upregulation prior to the pinocytosis.

This action triggers the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in the production of IL-1β [ 14 ]. Thus, it would appear that the calcium entering the circulation following bone resorption is capable of intensifying and prolonging the inflammatory response to burn injury and perhaps other conditions.

Furthermore, Olszak et al. Further evidence implicating calcium in the inflammatory response comes from Michalick and Kuebler [ 16 ] , who point out that transient receptor potential vanilloid TRPV -type 4, or TRPV4, a mechanosensitive calcium channel, is involved in neutrophil activation and chemotaxis.

TRPV4 has also been implicated in macrophage activation leading to lung injury following mechanical ventilation. These issues have also been reported in a rat model of immobilization and mechanical ventilation [ 17 ] in which it was shown that the pharmacologic immobilization of rats was accompanied by marked trabecular bone loss, thus liberating calcium into the circulation and possibly contributing to the inflammation described by Michalick and Kuebler [ 16 ].

Those children did not suffer significant resorptive bone loss and had no reduction in their bone mineral density. From these data, the researchers can infer that the additional amounts of calcium entering the circulation from bone resorption in the latter group was negligible.

Therefore, the researchers attempted to determine whether blood ionized calcium levels remained normal in children with small burns.

Throughout hospitalization, their mean ionized calcium concentration was 1. In no setting of pediatric burn injury is the circulating ionized calcium normal. Unfortunately, neither serum PTH concentrations nor quantitative urinary calcium data were available in this anonymized population.

In other words, even in small burns, the initial inflammatory response in children is sufficient to upregulate the parathyroid CaSR without the addition to the circulation of calcium from resorbing bone. In more severe burns, resorbed calcium entering the circulation would theoretically add to the urinary calcium load in pediatric burns.

However, the researchers do not have sufficient data at this time to document this statement. Despite the apparent uniformity of findings in burn patients under the age of 19, studies in adults yield an entirely different picture of ionized calcium and PTH response to severe burn injury.

In the researchers' patients [ 20 ] , and in the adult burns reported in the literature [ 21 ] [ 22 ] , severely burned adult patients were normo- or mildly hypercalcemic and euparathyroid or mildly hyperparathyroid. In the researchers' patients, the mean blood ionized calcium concentration was 1.

The mechanism explaining this difference is not apparent. However, it would appear likely that the ability of the parathyroid calcium-sensing receptor to respond to inflammatory cytokines by the upregulation and consequent development of hypocalcemic hypoparathyroidism is lost with age, sometime after the onset of puberty.

By age 19, there is still no change in the childhood response pattern of parathyroid CaSR upregulation in response to inflammatory cytokines, thus likely causing the age at the loss of response of the parathyroid CaSR to inflammatory cytokines to be at least in the early 20s.

This age approximates the time of acquisition of peak bone mass, and the relationship between these two developmental milestones requires further investigation. Likewise, sexual dimorphism was not apparent in the analysis of the results of circulating ionized calcium and PTH concentrations in children and adolescents past the onset of puberty, through the ages of 18—19 years.

References Klein, G. Histomorphometric and biochemical characterization of bone following acute severe burns in children. Bone , 17, — Evidence supporting a role of glucocorticoids in short-term bone loss in burned children.

Nielsen, P. Inhibition of PTH secretion by interleukin-1 beta in bovine parathyroid glands in vitro is associated with an up-regulation of the calcium-sensing receptor mRNA. Toribio, R.

Parathyroid hormone PTH secretion, PTH mRNA and calcium-sensing receptor mRNA expression in equine parathyroid cells and effects of interleukin IL -1, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha on equine parathyroid cell function.

Defined as having a waist circumference of greater than 88 cm for women and greater than cm for men. Nutrient Intakes of Study Participants Throughout the Intervention a. Receiving mg calcium carbonate per day plus 50 IU vitamin D3 per week.

We found a significant increase in mean serum 25 OH D concentrations among those in vitamin D group No significant changes in this biomarker were seen in individuals in the calcium These data indicate good adherence of study participants to vitamin D supplementation.

The weight change in all groups was less than 0. The Baseline 25 OH D, Inflammatory, and Adipocytokine Levels of Study Participants a. Serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers and adipocytokines at study baseline are shown in Table 3. We observed no significant differences in serum concentrations of adiponectin, leptin, TNF-α, IL-6, and hs-CRP between the 4 intervention groups at study baseline.

The effects of calcium, vitamin D, and joint calcium-vitamin D supplementation on circulating levels of inflammatory biomarkers and adipocytokines are indicated in Table 4.

After adjustment for baseline levels of inflammatory biomarkers, we observed that, compared with placebo, supplementation with calcium and vitamin D had no significant effects on serum adiponectin concentrations. Further adjustments for BMI did not remarkably alter the above-mentioned findings; however, the significant effect of calcium, vitamin D, and calcium-vitamin D cosupplementation on serum TNF-α concentrations became nonsignificant after adjustment for BMI, indicating that the effect might be mediated through obesity.

The Effect of Vitamin D and Calcium Supplementation on Inflammation and Adipocytokine Biomarkers a. In this randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of vitamin D and calcium supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes, calcium-vitamin D cosupplementation resulted in a significant reduction in circulating leptin, IL-6, and TNF-α concentrations compared with other groups.

Moreover, individuals in the calcium group tended to have greater reductions in serum hs-CRP levels than the other groups. However, supplementation with calcium and vitamin D had no significant effects on serum adiponectin levels after adjustment for baseline levels.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is among the first investigations that examined the effects of joint calcium-vitamin D supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers and adipocytokines of type 2 diabetic patients who were on oral hypoglycemic agents.

Although metformin might have some antiinflammatory effects, the groups were matched in terms of type and dosage of oral hypoglycemic agent use. Therefore, the effects we found would be independent of oral hypoglycemic agent use. It is currently recognized that inflammation is involved in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes 6 , Previous studies have shown that separate vitamin D or calcium supplementations may improve insulin sensitivity and promote β-cell survival 25 — However, there are very limited data from human studies that examined the effect of vitamin D or calcium supplementation on systemic inflammation in diabetes 15 , We found that calcium plus vitamin D supplementation led to decreased levels of serum leptin, IL-6, and TNF-α concentrations.

Previously reported trials about the effect of single vitamin D or calcium supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers in nondiabetic subjects have shown conflicting results 20 , In a study on British adults of Bangladeshi origin, 54 vitamin D-deficient subjects were randomized and given either a high dose 50 IU or a low dose IU of a depot oily injection of cholecalciferol, every 3 months, during 1 year.

The investigators came to the conclusion that reductions in hs-CRP levels were greater in the high than in the low treatment group 8. Others found that a daily supplement of In a 1-year supplementation study with cholecalciferol in persons, reductions in serum IL-6 levels were found Calcium supplementation has been shown to decrease tumor-promoting proinflammatory markers in sporadic colorectal adenoma patients However, some studies did not find any beneficial effect of vitamin D or calcium supplementation on inflammation 18 , Improving vitamin D status through supplementation with different dosages of vitamin D3 in healthy postmenopausal women did not affect inflammatory biomarkers These studies were short in duration and had included few subjects.

All of the above-mentioned studies used vitamin D or calcium supplementation alone, and we are aware of only a few studies that examined joint calcium-vitamin D supplementation 20 , Moreover, in another randomized controlled trial, daily supplementation with mg calcium citrate and IU vitamin D3 for 3 years had no significant effects on markers of systemic inflammation among those with normal fasting glucose It is worth mentioning that the latter was a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial designed for assessing bone mineral density.

This might explain why the investigators could not reach the beneficial effects of joint supplementation on inflammation. Furthermore, participants of that study were apparently healthy individuals who might have near the normal levels of inflammatory biomarkers. This is in opposite to our study, in which participants were persons with diabetes with elevated levels of inflammation.

In addition, the different dosages of calcium and vitamin D can provide further reasons for discrepant findings. It seems that using appropriate doses of calcium and vitamin D supplements in vitamin D insufficient type 2 diabetic patients might help in controlling the elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers and adipocytokines.

Because systemic inflammation is closely involved in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and associated complications such as dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis, lowering inflammatory biomarkers and adipocytokines through the use of calcium-vitamin D supplements might result in better glycemic and metabolic control of diabetic patients.

Several mechanisms may explain the beneficial effects of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers and adipocytokines in type 2 diabetic patients. Vitamin D interacts with vitamin D response elements in the promoter region of cytokine genes to interfere with nuclear transcription factors implicated in cytokine generation and action.

Moreover, vitamin D can down-regulate the activation of nuclear factor-κB, which is an important regulator of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines implicated in insulin resistance. Also, vitamin D interferes with cytokine generation by up-regulating the expression of calbindin, a cytosolic calcium-binding protein found in many tissues including pancreatic β-cells The mechanism of effects of calcium on inflammation is still unclear.

However, it has been claimed that calcitriol regulates the macrophage production of inflammatory factors via calcium-dependent mechanism. Therefore, reducing circulating calcitriol levels via increasing dietary calcium intake or calcium supplementation may regulate the macrophage and thereby attenuate inflammation In addition, it seems that calcium intake might influence inflammation through the suppression of PTH.

Circulating levels of IL-6 and TNF-alpha were elevated in primary hyperparathyroidism Therefore, it seems that PTH can regulate circulating levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, which stimulate the production of hs-CRP.

Strengths of this study include the double-blind randomized placebo controlled design, quantification of serum 25 OH D levels to examine the adherence to the vitamin D supplementation, the relatively good compliance with the supplement use, and taking the variety of confounders including baselines levels of biomarkers into account.

Moreover, due to the effect of season on vitamin D status, we confined the intervention into one season. Some limitations must also be considered. This study was conducted during summer. Therefore, the vitamin D status of subjects might not accurately reflect the effect of supplements.

However, all patients were vitamin D insufficient at study baseline, even in summer. Furthermore, to assess compliance, we measured serum vitamin D levels at the end, not throughout, the study eg, wk 4.

Because the study has been done among those who were using oral hypoglycemic agents, the findings cannot easily be extrapolated to other diabetic patients for example, those who are injecting insulin.

This study cannot suggest the appropriate dosages for vitamin D and calcium supplements for diabetic patients. To reach this, other studies with different dosages of calcium and vitamin D are required. In addition, a short duration of intervention might prohibit us to observe the effects of supplementation on some biomarkers of inflammation.

In conclusion, joint calcium-vitamin D supplementation resulted in an improved status of inflammation in vitamin D-insufficient type 2 diabetic patients. Further studies to determine the appropriate doses of calcium and vitamin D for these patients are warranted.

We thank the study participants for their participation in the current study. We also appreciate the Clinical Research Council of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for providing funding for the current project. The collaborations of Mrs Maryam Zare MSc student of nutrition, Isfahan Endocrine and Metabolism Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran as well as all of the laboratory personnel of Milad Laboratory are greatly acknowledged.

This paper is based on the MSc thesis of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences number Contribution of authors include the following: Marj.

and A. contributed in the conception, design, statistical analyses, and drafting of the manuscript. provided the scientific counseling. and Mary. contributed in the data collection. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

supervised the study. This work was supported by the Clinical Research Council, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. Mokdad AH , Ford ES , Bowman BA , et al.

Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors. Google Scholar. Wild S , Roglic G , Green A , et al. Global prevalence of diabetes. Diabetes Care. Esteghamati A , Gouya MM , Abbasi M , et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in the adult population of Iran.

Inflammatory markers and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in women. Pradhan AD , Manson JE , Rifai N , et al. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus.

King GL. The role of inflammatory cytokines in diabetes and its complications. J Periodontol. Pittas AG , Dawson-Hughes B , Li T , et al. Vitamin D and calcium intake in relation to type 2 diabetes in women.

Timms PM , Mannan N , Hitman GA , et al. Circulating MMP9, vitamin D and variation in the TIMP-1 response with VDR genotype: mechanisms for inflammatory damage in chronic disorders? Chagas CEA , Borges MC , Martini LA , et al. Focus on Vitamin D. inflammation and type 2 diabetes.

Palomer X , González-Clemente JM , Blanco-Vaca F , et al. Role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. Danescu LG , Levy S , Levy J. Vitamin D and diabetes mellitus. Panagiotakos DB , Pitsavos CH , Zampelas AD , et al. Dairy products consumption is associated with decreased levels of inflammatory markers related to cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy adults: the ATTICA study.

J Am Coll Nutr. Esmaillzadeh A , Azadbakht L. Dairy consumption and circulating levels of inflammatory markers among Iranian women. Public Health Nutr. da Silva Ferreira T , Torres MR , Sanjuliani AF.

Dietary calcium intake is associated with adiposity, metabolic profile, inflammatory state and blood pressure, but not with erythrocyte intracellular calcium and endothelial function in healthy pre-menopausal women.

Br J Nutr. Shab-Bidar S , Neyestani TR , Djazayery A , et al. Improvement of vitamin D status resulted in amelioration of biomarkers of systemic inflammation in the subjects with type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Metab Res Rev. Grossmann RE , Zughaier SM , Liu S , et al. Impact of vitamin D supplementation on markers of inflammation in adults with cystic fibrosis hospitalized for a pulmonary exacerbation. Eur J Clin Nutr. Wamberg L , Kampmann U , Stødkilde-Jørgensen H , et al.

Effects of vitamin D supplementation on body fat accumulation, inflammation, and metabolic risk factors in obese adults with low vitamin D levels—results from a randomized trial.

Eur J Intern Med. Wood AD , Secombes KR , Thies F , et al. Vitamin D3 supplementation has no effect on conventional cardiovascular risk factors: a parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Noda M , Mizoue T.

Relation between dietary calcium and vitamin D and risk of diabetes and cancer: a review and perspective. J Clin Metab Diabetes. Hopkins MH , Owen J , Ahearn T , et al.

Effects of supplemental vitamin D and calcium on biomarkers of inflammation in colorectal adenoma patients: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Cancer Prev Res Phila. Pittas AG , Harris SS , Stark PC , et al.

The effects of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on blood glucose and markers of inflammation in nondiabetic adults. Gannage-Yared MH , Azoury M , Mansour I , et al. Effects of a short-term calcium and vitamin D treatment on serum cytokines, bone markers, insulin and lipid concentrations in healthy post-menopausal women.

J Endocrinol Invest. Ainsworth BE , Haskell WL , Whitt MC , et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

Spranger J , Kroke A , Möhlig M , et al. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes: results of the Prospective Population-Based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition EPIC -Potsdam Study.

Inomata S , Kadowaki S , Yamatani T , et al. Effect of 1α25 OH -vitamin D3 on insulin secretion in diabetes mellitus. Bone Miner. Sanchez M , de la Sierra A , Coca A , et al. Oral calcium supplementation reduces intraplatelet free calcium concentration and insulin resistance in essential hypertensive patients.

Major GC , Alarie F , Dore J , et al. Supplementation with calcium, vitamin D enhances the beneficial effect of weight loss on plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr. Neyestani TR , Nikooyeh B , Alavi-Majd H , et al. Improvement of vitamin D status via daily intake of fortified yogurt drink either with or without extra calcium ameliorates systemic inflammatory biomarkers, including adipokines, in the subjects with type 2 diabetes.

Beilfuss J , Berg V , Sneve M , et al. Effects of a 1-year supplementation with cholecalciferol on interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α and insulin resistance in overweight and obese subjects. Sokol SI , Srinivas V , Crandall JP , et al. The effects of vitamin D repletion on endothelial function and inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease.

Vasc Med. Seshadria KG , Tamilselvana B , Rajendrana A. Role of vitamin D in diabetes. J Endocrinol Metab. Sun X , Zemel MB. Calcitriol and calcium regulate cytokine production and adipocyte—macrophage cross-talk.

J Nutr Biochem. Grey A , Mitnick MA , Shapses S , Ellison A , Gundberg C , Insogna K. Circulating levels of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α are elevated in primary hyperparathyroidism and correlate with markers of bone resorption—a clinical research center study.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Sign In or Create an Account.

Calcium and inflammation Quadros Calcihm, Calcium and inflammation International University Follow. Although the etiology of genetic cases of AD has been attributed to mutations in presenilin and amyloid precursor protein APP genes, in most Calcium and inflammation cases of AD, inflammatin etiology is CCalcium unknown and Calccium predisposing factors Inflammatioh contribute Callcium the pathology Antimicrobial barrier technology AD. Predominant among these possible predisposing factors that have been implicated in AD are age, hypertension, traumatic brain injury, diabetes, chronic neuroinflammation, alteration in calcium levels and oxidative stress. Since both inflammation and altered calcium levels are implicated in the pathogenesis of AD, we wanted to study the effect of altered levels of calcium on inflammation and the subsequent effect of selective calcium channel blockers on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Our hypothesis is that Abeta depending on it conformation, may contribute to altered levels of intracellular calcium in neurons and glial cells.

0 thoughts on “Calcium and inflammation”