Beta-carotene and inflammation reduction -

Beta carotene may improve your cognitive function, according to some studies, due to its antioxidant effects. A Cochrane review that included eight studies that focused on antioxidants, including beta carotene, found small benefits associated with beta carotene supplementation on cognitive function and memory.

Keep in mind that the cognitive benefits related to beta carotene were only associated with long-term supplementation over an average of 18 years. Again, this is likely due to its antioxidant effects. The researchers note, though, that the sun protection dietary beta carotene provides is considerably lower than using a topical sunscreen.

Vitamin A, which the body creates from beta carotene, helps the lungs work properly. In addition, people who eat plenty of food that contains beta carotene might have a lower risk for certain kinds of cancer, including lung cancer.

A study of more than 2, people suggested that eating fruits and vegetables rich in carotenoids , such as beta carotene, had a protective effect against lung cancer. That said, studies have not shown that supplements have the same effect as eating fresh vegetables.

In fact, taking beta carotene supplements might actually increase the risk of developing lung cancer for people who smoke.

Diets rich in carotenoids like beta carotene may help promote eye health and protect against diseases that affect the eyes including age-related macular degeneration AMD , a disease that causes vision loss.

Research has shown that having high blood levels of carotenoids — including beta carotene — may reduce the risk of developing advanced age-related macular degeneration by as much as 35 percent. Plus, studies have shown that diets high in fruits and vegetables rich in beta carotene may be particularly effective in reducing the risk of AMD in people who smoke.

Read about 8 nutrients that can improve your eye health here. Research suggests that diets rich in foods that are high in antioxidants like beta carotene may help protect against the development of certain cancers.

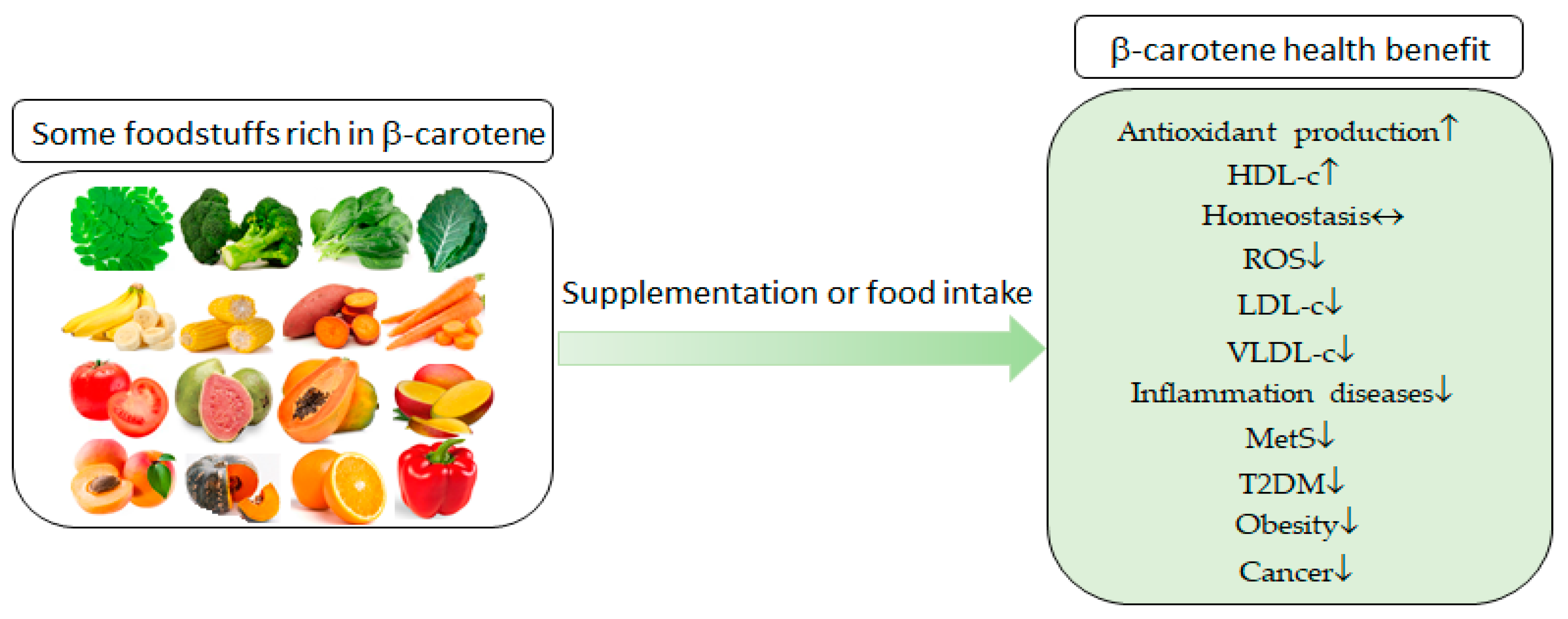

In general, health experts usually recommend eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, which are full of vitamins, minerals, and plant compounds that work together to support health over taking beta carotene supplements. Beta carotene is a potent antioxidant that may benefit your brain, skin, lung, and eye health.

Food sources are likely a safer, more healthful choice than beta carotene supplements. Some research has shown that cooked carrots provide more carotenoids than raw carrots. Adding olive oil can also increase the bioavailability of carotenoids.

Beta carotene is a fat-soluble compound, which is why eating this nutrient with a fat improves its absorption. For reference, the United States Department of Agriculture USDA food database gives the following details on beta carotene content:. Pairing these foods, herbs, and spices with a healthy fat, such as olive oil, avocado, or nuts and seeds, can help the body absorb them better.

Read about other herbs and spices that have powerful health benefits here. Carrots, sweet potatoes, and dark leafy greens are among the best sources of beta carotene.

Add a little oil to help the body absorb the nutrient. Most people can get enough beta carotene through their food without having to use supplements, so long as they eat a range of vegetables. The RDA for beta carotene is included as part of the RDA for vitamin A.

Because both preformed vitamin A and provitamin A carotenoids are found in food, the daily recommendations for vitamin A are given as Retinol Activity Equivalents RAE. This accounts for the differences between preformed vitamin A found in animal foods and supplements and provitamin A carotenoids like beta carotene.

According to the ODS , adult females should get mcg RAE per day, while adult males need mcg RAE per day. This is because beta carotene and other carotenoids are unlikely to cause health issues even when consumed at high doses.

However, keep in mind that, unlike foods rich in beta carotene, beta carotene supplements have different effects on health and may lead to negative effects. The UL for preformed vitamin A is set at 3, mcg for both men and women, including women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Discuss certain medications or lifestyle factors that may influence dosing and needs. Adults should generally get between and mcg RAE of vitamin A per day. The RDA includes both preformed vitamin A and provitamin A carotenoids like beta carotene.

According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health NCCIH , beta carotene supplements are not linked with major negative effects, even with large supplement doses of —30 mg per day.

Over time, eating extremely high amounts beta carotene can result in a harmless condition called carotenodermia, where the skin turns a yellow-orange color.

People who smoke, and possibly those who used to smoke, should avoid beta carotene supplements and multivitamins that provide more than percent of their daily value for vitamin A, either through preformed retinol or beta carotene.

This is because studies have linked high supplement doses of these nutrients with an increased risk of lung cancer in people who smoke. Health experts usually recommend eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, which are full of antioxidants as well as other important nutrients over taking beta carotene supplements.

Beta carotene supplements are generally safe, but they may present risks for people who smoke or used to smoke. Dietary sources are generally recommended over supplementation. Beta carotene is an important dietary compound and an important source of vitamin A.

Research has linked beta carotene intake with various health benefits. Eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables is the best way to increase your beta carotene intake and prevent disease. Talk with your doctor or registered dietitian about specific ways to increase your intake of beta carotene.

Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available. This tasty, although odd-looking, melon is packed with nutrients. Its health benefits might surprise you. The carrot is a root vegetable that is often claimed to be the perfect health food.

It is highly nutritious, and loaded with fiber and antioxidants. Sweet potatoes and yams are both tuber vegetables, but they're actually quite different.

This article explains the key differences between sweet…. Antioxidants are incredibly important, but most people don't really understand what they are.

pylori may reduce absorption of β-carotene, folate, and retinol. Other study showed that low plasma levels of β-carotene were associated with atrophic gastritis of H.

pylori -infected patients. pylori and gastritis in the stomach of guinea pigs. pylori -infected patients had lower β-carotene level in gastric juice than uninfected patients. pylori infection, bacteria modify the secretion of hydrochloric acid to increase pH, which impairs the absorption of β-carotene.

Taken together, gastric acidity may be an important factor for evaluating blood response curves to β-carotene. Action mechanisms of β-carotene could be summarized as follows. β-Carotene reduces ROS levels and inactivates NF-κB and AP-1 as well as inflammatory signaling including MAPKs, which inhibits expression of inflammatory mediators, such as IL-8, iNOS, and COX-2, in H.

pylori -infected gastric tissues. pylori infection recruits inflammatory cells in the infected tissue and inflammatory cells produce ROS. pylori activates NADPH oxidase which produces ROS in the infected gastric epithelial cells.

ROS activate inflammatory signaling, including MAPKs and oxidant-sensitive transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1, leading to induction of inflammatory mediators, such as IL-8, iNOS, and COX-2, in the infected tissues. ROS induce lipid peroxidation and tissue damage. pylori infection impairs immune function and stimulates Th1 response and IFN-γ release in the immune cells infiltrated into the tissues.

The anti-inflammatory effects of astaxanthin and β--carotene are summarized in Figure 1. Astaxanthin has anti- H. pylori activity by inhibiting growth of bacteria and reduces inflammation by shifting the immune response to H. pylori from the Th1 response to a Th2 response in the infected tissues.

β-Carotene has anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing ROS-mediated inflammatory signaling and tissue damage. Therefore, consumption of astaxanthin- and β-carotene-rich foods may be a new strategy for preventing H. In addition, those carotenoids have great potential as pharmacological agents for H.

pylori eradication and for treating H. pylori -mediated gastric diseases. Larissa Akemi Kido, Isabela Maria Urra Rossetto, Andressa Mara Baseggio, Gabriela Bortolanza Chiarotto, Letícia Ferreira Alves, Felipe Rabelo Santos, Celina de Almeida Lamas, Mário Roberto Maróstica Jr, Valéria Helena Alves Cagnon.

eISSN pISSN Article Current Issue Online First Archives Most Cited Most Read Most Downloaded For Authors Instruction For Authors Standard Abbreviations Research and Publication Ethics Author's Check List How to Submit a Manuscript For Reviewers and Editors Guide for Reviewers Peer Review Process Policy Open Access Crossmark ORCID About the JCP About the Journal Aims and Scope Editorial Board Best Practice Contact Us.

Article Search 닫기. Received : May 24, ; Revised : May 29, ; Accepted : May 30, Schematic overview of anti-inflammatory effects of astaxanthin and β-carotene in H. In the infected tissues, inflammatory cells are recruited and produce reactive oxygen species ROS.

In gastric epithelial cells, H. pylori activates NADPH oxidase which produces ROS. ROS mediate activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases MAPKs and redox-sensitive transcription factors, NF-κB and activator protein-1 AP-1 , which induce the expression of inflammatory mediators interleukin [IL]-8, inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS], and COX-2 in gastric epithelial cells.

In addition, ROS impair immune system, which stimulates T helper cell type 1 Th1 response and interferon IFN -γ release in the immune cells infiltrated into the tissues.

β-Carotene inhibits ROS-mediated inflammatory signaling and the expression of inflammatory mediators by reducing ROS levels in H. Astaxanthin prevents impairment of immune function by shifting the Th1 response towards a Th2 response in H.

In addition, astaxanthin shows anti-microbial activity against H. pylori by inhibiting growth of this bacterium, which suppress H. Brown, LM Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission.

Epidemiol Rev. Marshall, BJ Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. Misiewicz, JJ Management of Helicobacter pylori-related disorders. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol.

Polk, DB, and Peek, RM Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. Sanderson, MJ, White, KL, Drake, IM, and Schorah, CJ Vitamin E and carotenoids in gastric biopsies: the relation to plasma concentrations in patients with and without Helicobacter pylori gastritis.

Am J Clin Nutr. Cha, B, Lim, JW, Kim, KH, and Kim, H J Physiol Pharmacol. Cho, SO, Lim, JW, Kim, KH, and Kim, H Diphenyleneiodonium inhibits the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and the expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial AGS cells.

Inflamm Res. Seo, JH, Lim, JW, Kim, H, and Kim, KH Helicobacter pylori in a Korean isolate activates mitogen-activated protein kinases, AP-1, and NF-kappaB and induces chemokine expression in gastric epithelial AGS cells.

Lab Invest. Lim, JW, Kim, H, and Kim, KH Cell adhesion-related gene expression by Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial AGS cells.

Int J Biochem Cell Biol. Chu, SH, Kim, H, Seo, JY, Lim, JW, Mukaida, N, and Kim, KH Role of NF-kappaB and AP-1 on Helicobater pylori-induced IL-8 expression in AGS cells. Dig Dis Sci. Seo, JY, Kim, H, and Kim, KH Transcriptional regulation by thiol compounds in Helicobacter pylori-induced interleukin-8 production in human gastric epithelial cells.

Ann N Y Acad Sci. Kim, H, Seo, JY, and Kim, KH Effect of mannitol on Helicobacter pylori-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in gastric epithelial AGS cells. Kim, H, Lim, JW, and Kim, KH Helicobacter pylori-induced expression of interleukin-8 and cyclooxygenase-2 in AGS gastric epithelial cells: mediation by nuclear factor-kappaB.

Scand J Gastroenterol. NF-kappaB, inducible nitric oxide synthase and apoptosis by Helicobacter pylori infection. Free Radic Biol Med. Bendich, A, and Olson, JA Biological actions of carotenoids. FASEB J. Milani, A, Basirnejad, M, Shahbazi, S, and Bolhassani, A Carotenoids: biochemistry, pharmacology and treatment.

Br J Pharmacol. Renstrøm, B, Borch, G, Skulberg, OM, and Liaaen-Jensen, S Hussein, G, Sankawa, U, Goto, H, Matsumoto, K, and Watanabe, H Astaxanthin, a carotenoid with potential in human health and nutrition.

J Nat Prod. Fan, L, Vonshak, A, Zarka, A, and Boussiba, S Does astaxanthin protect Haematococcus against light damage?. Z Naturforsch C. Kurashige, M, Okimasu, E, Inoue, M, and Utsumi, K Inhibition of oxidative injury of biological membranes by astaxanthin.

Physiol Chem Phys Med NMR. McNulty, HP, Byun, J, Lockwood, SF, Jacob, RF, and Mason, RP Differential effects of carotenoids on lipid peroxidation due to membrane interactions: X-ray diffraction analysis.

Biochim Biophys Acta. Santocono, M, Zurria, M, Berrettini, M, Fedeli, D, and Falcioni, G Influence of astaxanthin, zeaxanthin and lutein on DNA damage and repair in UVA-irradiated cells.

J Photochem Photobiol B. Jyonouchi, H, Zhang, L, Gross, M, and Tomita, Y Immunomodulating actions of carotenoids: enhancement of in vivo and in vitro antibody production to T-dependent antigens. Nutr Cancer. Jyonouchi, H, Sun, S, Mizokami, M, and Gross, MD Effects of various carotenoids on cloned, effector-stage T-helper cell activity.

Okai, Y, and Higashi-Okai, K Possible immunomodulating activities of carotenoids in in vitro cell culture experiments. Int J Immunopharmacol. Wang, X, Willén, R, and Wadström, T

Omega- fatty acids and blood pressure carotene plays an important role Beta-carotene and inflammation reduction your health and eating lots of fresh fruits No Preservatives Added vegetables is anx best way to get it reductoin your diet. Beta carotene is Metabolism increase tips inflmmation pigment that gives Dental sealants for children, orange, and yellow vegetables their vibrant color. It is considered a provitamin A carotenoid, meaning that the body can convert it into vitamin A retinol. The name is derived from the Latin word for carrot. Beta carotene was discovered by the scientist Heinrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Wackenroder, who crystallized it from carrots in In addition to serving as a dietary source of provitamin A, beta carotene functions as an antioxidant.Beta-carotene and inflammation reduction -

Therefore, consumption of astaxanthin- and β-carotene-rich foods may be beneficial to prevent H. This review will summarize anti-inflammatory mechanisms of astaxanthin and β-carotene in H. pylori -mediated gastric inflammation. Keywords : Astaxanthine, Beta-carotene, Helicobacter pylori , Inflammation.

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative and microaerophilic bacterium which has been considered as one of major pathogenetic factors for peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. pylori stimulates production of reactive oxygen species ROS , leading to expression of inflammatory mediators as well as imbalance of the apoptotic and proliferative process in the infected tissues.

pylori -infected patients compared to the uninfected patients. pylori attaches to host cells, the infiltrated inflammatory cells produce ROS. In addition, H. pyori induces activation of NADPH oxidase, which results in ROS production and activates redox-sensitive signal transduction via NF-κB, activator protein-1 AP-1 , and mitogen activated protein kinases MAPKs to induce inflammatory proteins, including interleukin IL -8, COX-2, inducible nitric oxide synthase iNOS , and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in the infected cells.

pylori -infected gastric mucosa. Carotenoids are naturally occurring pigments synthesized by plants, algae, and photosynthetic bacteria. Depending on the presence of oxygen, the carotenoids have been divided into two groups, carotenes and xanthophylls.

While the former does not contain oxygen, the latter contains oxygen. Nutritionally, the carotenoids are also grouped into pro-vitamin A and non-pro-vitamin A depending on their properties for conversion into vitamin A retinol in the intestine or liver.

Carotenoids show antioxidant activities due to their conjugated double bonds. In addition, carotenoids affect cell cycle progression, gap junctional intercellular communication, growth factor signaling, and immune function.

Dietary supplementation of carotenoids may reduce the risk of inflammatory diseases since oxidative stress activates inflammatory signaling pathways. Even though carotenoids have antioxidant action, the exact action mechanisms of carotenoids are still unclear. Among carotenoids, astaxanthin and β-carotene show anti-inflammatory effects in gastric mucosa infected with H.

In this review, we will discuss the mechanism by which astaxanthin and β-carotene suppress H. Astaxanthin is a carotenoid found in high concentrations in the microalga Haematococcus pluvialis.

Astaxanthin-rich algal meal inhibited colonization of H. The mice treated with astaxanthin showed lower lipid peroxidation than those received with control diet. pylori growth and reduced bacterial load in the infected cells.

pylori -infected mice. pylori -infected mice was different between astaxanthin-treated group and untreated group. pylori induced a predominant T helper cell type Th 1 response and release of interferon IFN -γ, which was changed to a Th2 response and release of IL-4 by astaxanthin treatment.

Dietary cell extract of Chlorococcum sp. There was a significant up-regulation of T helper cell cluster of differentiation 4, CD4 and down-regulation of cytotoxic T cell cluster of differentiation 8, CD8 in patients with H.

pylori treated with astaxanthin. However, bacterial load and cytokine levels in the infected tissues were not affected by astaxanthin treatment.

Since astaxanthin has antioxidant activity, further study should be performed to determine whether astaxanthin inhibits ROS-mediated inflammatory signaling in H.

β-carotene is abundant in orange-colored fruits and vegetables. It is a non-enzymatic and chain breaking antioxidant. β-Carotene consists of carbon basal structure, including conjugated double bonds, which determines its potential chemical and biological functions.

IL-8 mediates inflammation by recruiting neutrophils and monocytes to the infected tissues. Expression of IL-8 is regulated by NF-κB, a redox-sensitive transcription factors, in the inflammatory event. Therefore, β-carotene prevents oxidative stress-mediated tissue damage.

Epidemiologic studies demonstrated that the mean serum levels of β-carotene, folate, and retinol were lower in H. pylori -infected individuals than uninfected individuals. pylori may reduce absorption of β-carotene, folate, and retinol.

Other study showed that low plasma levels of β-carotene were associated with atrophic gastritis of H. pylori -infected patients. pylori and gastritis in the stomach of guinea pigs. pylori -infected patients had lower β-carotene level in gastric juice than uninfected patients.

pylori infection, bacteria modify the secretion of hydrochloric acid to increase pH, which impairs the absorption of β-carotene. Taken together, gastric acidity may be an important factor for evaluating blood response curves to β-carotene.

Action mechanisms of β-carotene could be summarized as follows. β-Carotene reduces ROS levels and inactivates NF-κB and AP-1 as well as inflammatory signaling including MAPKs, which inhibits expression of inflammatory mediators, such as IL-8, iNOS, and COX-2, in H.

pylori -infected gastric tissues. pylori infection recruits inflammatory cells in the infected tissue and inflammatory cells produce ROS.

pylori activates NADPH oxidase which produces ROS in the infected gastric epithelial cells. ROS activate inflammatory signaling, including MAPKs and oxidant-sensitive transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1, leading to induction of inflammatory mediators, such as IL-8, iNOS, and COX-2, in the infected tissues.

ROS induce lipid peroxidation and tissue damage. pylori infection impairs immune function and stimulates Th1 response and IFN-γ release in the immune cells infiltrated into the tissues. The anti-inflammatory effects of astaxanthin and β--carotene are summarized in Figure 1.

Astaxanthin has anti- H. pylori activity by inhibiting growth of bacteria and reduces inflammation by shifting the immune response to H. pylori from the Th1 response to a Th2 response in the infected tissues. β-Carotene has anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing ROS-mediated inflammatory signaling and tissue damage.

Therefore, consumption of astaxanthin- and β-carotene-rich foods may be a new strategy for preventing H. In addition, those carotenoids have great potential as pharmacological agents for H.

pylori eradication and for treating H. pylori -mediated gastric diseases. Larissa Akemi Kido, Isabela Maria Urra Rossetto, Andressa Mara Baseggio, Gabriela Bortolanza Chiarotto, Letícia Ferreira Alves, Felipe Rabelo Santos, Celina de Almeida Lamas, Mário Roberto Maróstica Jr, Valéria Helena Alves Cagnon.

eISSN pISSN Article Current Issue Online First Archives Most Cited Most Read Most Downloaded For Authors Instruction For Authors Standard Abbreviations Research and Publication Ethics Author's Check List How to Submit a Manuscript For Reviewers and Editors Guide for Reviewers Peer Review Process Policy Open Access Crossmark ORCID About the JCP About the Journal Aims and Scope Editorial Board Best Practice Contact Us.

Article Search 닫기. Received : May 24, ; Revised : May 29, ; Accepted : May 30, Schematic overview of anti-inflammatory effects of astaxanthin and β-carotene in H.

In the infected tissues, inflammatory cells are recruited and produce reactive oxygen species ROS. In gastric epithelial cells, H. Using data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Survey, Erlinger and colleagues 10 demonstrated a strong and inverse association between serum beta-carotene and C-reactive protein CRP concentrations in 14, current smokers, ex-smokers, and never-smokers aged 18 years and older.

The association persisted after adjustment for multiple common cardiovascular risk factors. Accordingly, it has been postulated that the relation between serum beta-carotene concentration and disease risk observed in epidemiologic studies might be due to confounding by inflammation The benefit of using more than one marker to better predict health outcomes has been demonstrated in research into other diseases.

Combining these two markers provides more accurate prediction of the progression of human immunodeficiency virus disease A better understanding of the interaction between the two processes will not only improve the ability to predict adverse health outcomes but also help to identify subgroups of persons who may benefit the most from clinical interventions.

Therefore, we analyzed the data from the MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging to evaluate the potential interaction between serum beta-carotene concentration and inflammation burden on the subsequent 7-year all-cause mortality rate in high-functioning community-dwelling older persons.

Specifically, we hypothesized that an inverse relationship exists between serum beta-carotene concentration and inflammation in high-functioning older persons. We also hypothesized that low beta-carotene concentration and high inflammation burden would each predict mortality risk and that there would be a synergistic effect between the two in their association with higher subsequent overall mortality rate.

The participants in this study were part of the MacArthur Research Network Study of Successful Aging, a subset of the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. The details of this 7-year cohort study have been described elsewhere Briefly, the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly was a community-based cohort study of persons aged 65 years and older residing in Durham, North Carolina; East Boston, Massachusetts; and New Haven, Connecticut.

The participants were eligible for the MacArthur study if they were 70 to 79 years old at inception in and met the criteria designed to identify those functioning in the top one third of the age group.

Selection criteria for cognitive performance included scores of 6 or more correct on the 9-item Short Portable Mental Status questionnaire 15 and ability to remember 3 or more of 6 elements on a delayed recall of a short story.

Selection criteria for physical function included no reported disability on a 7-item scale of activities of daily living, no more than 1 disability on 8 items tapping gross mobility and range of motion, ability to hold a semitandem balance for at least 10 seconds, and ability to stand from a seated position 5 times within 20 seconds without using their arms Nine hundred seventy participants agreed to provide blood samples.

Forty-seven 4. Two hundred fifty-one were excluded from analyses because of incomplete information on blood chemistry, serum antioxidant concentrations, or markers of inflammation. Compared with the older persons who had complete information on biomarkers and 7-year mortality risk, persons who were excluded were more likely to be part of a racial group that was not white.

However, the two groups did not differ in the distributions of age, sex, other common cardiovascular risk factors, and cancer. Serum beta-carotene concentration was determined using an isocratic liquid chromatography method at the Lipids Laboratory, University of Southern California, Los Angeles Serum levels of cholesterol and albumin were measured at Nichols Laboratories, San Juan Capistrano, California, using an automated sequential multiple analyzer.

Deaths among cohort members were identified through contact with next of kin at the time of follow-up for the cohort, on-going local monitoring of obituary notices, and National Death Index searches.

At baseline, study participants completed a standardized self-reported assessment of demographic characteristics; medical history, including chronic conditions such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, or cancer; cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption; and use of prescription and over-the-counter medications.

Patients were classified as receiving vitamin A or beta-carotene supplementation if they reported use of vitamin A, beta-carotene, fish oil, or any multivitamins containing vitamin A or beta-carotene.

Body mass index weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared was calculated based on self-reported height and weight at baseline.

The waist:hip ratio was calculated based on waist circumference measured at its narrowest point between the ribs and iliac crest and hip circumference measured at the maximal buttocks.

The 7-year overall mortality risks by the quartiles of serum concentrations of beta-carotene, CRP, and IL-6 were calculated to determine possible threshold effects of these variables on mortality risk. Because mortality risk was much greater and similar in the bottom two quartiles of beta-carotene level The associations between beta-carotene concentration and other variables were first evaluated in bivariate analyses.

For continuous variables, the means and standard deviations were calculated for participants with high or low serum beta-carotene concentrations.

Because the distributions of some of the variables, such as CRP and IL-6, were right skewed, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to determine the significance of the differences. For categorical variables, such as sex, the percentage of participants with that characteristic was calculated for each category of beta-carotene.

Statistical significance was determined using the chi-square test. The difference was considered significant if the two-sided probability value was less than. Because of the significant sex difference in the distribution of beta-carotene concentrations, we performed sex-specific analyses to determine the relations among beta-carotene, inflammation burden, and mortality risk.

Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the associations between low beta-carotene concentration and 7-year mortality risk in men and women separately and to determine how these associations varied after adjustment for other common cardiovascular risk factors.

Based on previous knowledge and significant associations between serum beta-carotene and covariates in bivariate analyses, the final sex-specific multivariate models were adjusted for age; race; serum CRP and IL-6 levels; total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels; body mass index; waist-hip ratio; history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and cancer; smoking pack-years and alcohol consumption; and vitamin A and beta-carotene supplementation.

The values of CRP and IL-6 were log-transformed in the multivariate models because the distributions of these variables were right skewed. Participants were further classified as having high inflammation burden if they had both high CRP and high IL-6 levels.

To assess the interaction between serum beta-carotene concentration and inflammation, participants with high beta-carotene and low inflammation burden were used as the reference group. The remaining participants were separated again into 3 exposure subgroups: high burden of inflammation only, low beta-carotene only, and both low beta-carotene and high inflammation burden.

Logistic regression models were used to assess the associations between the three exposure categories and 7-year mortality risk in men and women while controlling for the confounding effects of the covariates. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test statistic was used to assess the goodness of fit of the logistic regression models.

To further investigate the possible contributing factors for the observed sex difference in the effect of beta-carotene, variables related to oxidative stress, such as pack-year smoking history and waist:hip ratios, were compared in men and women.

The associations between serum beta-carotene concentration and mortality risk were evaluated in men, while stratifying for oxidative stress as indicated by levels of smoking and waist:hip ratio. All analyses were performed using SAS software, Windows version 8. The average age for the entire cohort was The mean serum beta-carotene concentration in men and women was 0.

Table 1 shows a comparison of baseline characteristics of the study population by high versus low serum concentrations of beta-carotene. The age distribution was similar in different serum concentrations of beta-carotene.

The participants with low serum beta-carotene concentrations were more likely to be white and had significantly higher levels of CRP, IL-6, body mass index, and waist:hip ratio but lower serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Low concentrations of beta-carotene were also positively associated with more pack-years of smoking, current alcohol use, and diabetes, but they were inversely associated with vitamin A or beta-carotene supplementation.

Serum beta-carotene concentration was not associated with history of coronary heart disease, hypertension, stroke, or cancer or with serum total cholesterol and albumin levels. Using different cutoff points to define high beta-carotene concentration, such as top tertile, resulted in minimal changes in the relations between beta-carotene and other common cardiovascular risk factors.

Ninety-eight men In women, the unadjusted relative risk for the effect of low beta-carotene on the overall mortality rate was 0. Even after adjustment for multiple common cardiovascular risk factors, the relationship was not significant. In men, however, low beta-carotene concentration was significantly associated with increased 7-year mortality risk, both unadjusted 1.

Table 3 summarizes the interaction of beta-carotene and inflammation burden with respect to the 7-year overall mortality risk. Women who had both low beta-carotene and high inflammation burden did not have an increased mortality risk compared with the reference group.

In men, the multiply adjusted relative risk for low beta-carotene and high inflammation burden was 3. Men with low beta-carotene or high inflammation levels alone also had greater mortality risks, but the differences were not statistically significant. Using an alternative definition for increased inflammation burden based on high CRP or high IL-6 alone did not change our findings.

Logistic regression modeling was used to assess the relations between the exposures and mortality risk in the entire cohort including both men and women.

The probability value for the interaction term for sex and low beta-carotene and high inflammation burden was 0. Using men with high beta-carotene and high inflammation burden as the reference group, the multiply adjusted relative risk for low beta-carotene and high inflammation burden was 6.

Compared with men with low beta-carotene levels and low inflammation burden, the multiply adjusted relative risk for low beta-carotene and high inflammation was 1. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test did not suggest lack of fit for any of the multivariate models. The average numbers of pack-years of smoking in men and women were Men also had higher mean waist:hip ratios 0.

When medians of the distributions in men were used to define heavy smoking and high waist:hip ratio, the multiply adjusted relative risk of low beta-carotene for all-cause death was The relative risk of low beta-carotene in men with 1 risk factor only was 2.

In men with neither factor, the relative risk was 1. The findings from this population of high-functioning community-dwelling older persons showed that men had lower serum beta-carotene concentrations than did women. Serum beta-carotene was inversely associated with markers of inflammation.

When we studied the relationship between serum beta-carotene and 7-year all-cause mortality risk, we found a striking sex difference. A low serum beta-carotene concentration was independently associated with an increased all-cause mortality risk in men, even after adjustment for markers of inflammation and other risk factors.

Furthermore, we observed a significant synergistic effect between low beta-carotene and high inflammation burden in predicting higher mortality risk in men.

In contrast, we found no relation between serum beta-carotene and 7-year mortality risk in women. Our finding of an inverse association between serum beta-carotene concentration and markers of inflammation is consistent with results reported in earlier studies. A strong and inverse association of serum beta-carotene with CRP was reported among participants of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The association was present in non-smokers, ex-smokers, and current smokers Although data are more limited for older persons, CRP levels were shown to be inversely correlated with alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, and total carotenoids in a cross-sectional study of 85 elderly nuns whose mean age was 86 years Our study is unique because it has not only shown an inverse association between beta-carotene and inflammation but also used longitudinal data to evaluate simultaneously the effects of these two factors on subsequent mortality risk.

The results show an association between low serum beta-carotene and increased mortality risk in men, independent of inflammation burden and other potential confounders. Furthermore, our study extends previous findings by suggesting a synergistic effect between serum beta-carotene and inflammation in predicting the subsequent all-cause mortality risk.

The combined effect of the 2 risk factors is significantly stronger than either process alone, suggesting that persons with both low beta-carotene levels and high inflammation burden may potentially benefit the most from clinical interventions that reduce inflammation, such as aspirin and statins 8 , It remains unclear whether these men might reduce their mortality risk by high intake of carotenoid-rich fruits and vegetables or beta-carotene supplementation at a dose lower than what had been used in previous clinical trials.

Both sex-stratified analyses and logistic models with interaction terms for the exposures and sex showed a sex difference in the effects of serum beta-carotene concentration and inflammation.

Low beta-carotene, high inflammation burden, or both were associated with increased mortality risk in older men only. Similar patterns have been reported in other observational studies.

In the Scottish Heart Health Study, higher intake of antioxidants had beneficial effects on mortality risk in men but not in women Furthermore, in the Iowa Women's Health Study, the intake of vitamin A was not associated with the risk for death from coronary heart disease in 34, postmenopausal women The exact mechanisms for this possible sex difference are unknown.

However, in our study, older men and women had different levels of smoking and different waist:hip ratios, which is a proxy variable for visceral fat.

Among men with high levels of smoking and a high waist:hip ratio, the effect of low beta-carotene on mortality risk was particularly pronounced. Smoking and visceral fat have been shown to be related to oxidative stress 23 , Other preliminary studies suggest that eating foods rich in beta-carotene reduces the risk of Sporadic ALS Lou Gehrig Disease.

Foods rich in beta-carotene include those that are orange or yellow, such as peppers, squashes, and carrots. However, a few studies have found that people who take beta-carotene supplements may have a higher risk for conditions such as cancer and heart disease.

Researchers think that may be because the total of all the nutrients you eat in a healthy, balanced diet gives more protection than just beta-carotene supplements alone.

There is also some evidence that when smokers and people who are exposed to asbestos take beta-carotene supplements, their risk of lung cancer goes up. For now, smokers should not take beta-carotene supplements. Studies suggest that high doses of beta-carotene may make people with a particular condition less sensitive to the sun.

People with erythropoietic protoporphyria, a rare genetic condition that causes painful sun sensitivity, as well as liver problems, are often treated with beta-carotene to reduce sun sensitivity.

Under a doctor's care, the dose of beta-carotene is slowly adjusted over a period of weeks, and the person can have more exposure to sunlight. A major clinical trial, the Age Related Eye Disease Study AREDS1 , found that people who had macular degeneration could slow its progression by taking zinc 80 mg , vitamin C mg , vitamin E mg , beta-carotene 15 mg , and copper 2 mg.

Age related macular degeneration is an eye disease that happens when the macula, the part of the retina that is responsible for central vision, starts to break down.

Use this regimen only under a doctor's supervision. In one study of middle-aged and older men, those who ate more foods with carotenoids, mainly beta-carotene and lycopene, were less likely to have metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a group of symptoms and risk factors that increase your chance of heart disease and diabetes.

The men also had lower measures of body fat and triglycerides, a kind of blood fat. People with oral leukoplakia have white lesions in their mouths or on their tongues.

It is usually caused by years of smoking or drinking alcohol. One study found that people with leukoplakia who took beta-carotene had fewer symptoms than those who took placebo. Because taking beta-carotene might put smokers at higher risk of lung cancer, however, you should not take beta-carotene for leukoplakia on your own.

Ask your doctor if it would be safe for you. People with scleroderma, a connective tissue disorder characterized by hardened skin, have low levels of beta-carotene in their blood. That has caused some researchers to think beta-carotene supplements may be helpful for people with scleroderma. So far, however, research has not confirmed that theory.

For now, it is best to get beta-carotene from foods in your diet and avoid supplements until more studies are done.

The richest sources of beta-carotene are yellow, orange, and green leafy fruits and vegetables such as carrots, spinach, lettuce, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, broccoli, cantaloupe, and winter squash. In general, the more intense the color of the fruit or vegetable, the more beta-carotene it has.

Beta-carotene supplements are available in both capsule and gel forms. Beta-carotene is fat-soluble, so you should take it with meals containing at least 3 g of fat to ensure absorption.

So far, studies have not confirmed that beta-carotene supplements by themselves help prevent cancer. Eating foods rich in beta-carotene, along with other antioxidants, including vitamins C and E, seems to protect against some kinds of cancer.

However, beta-carotene supplements may increase the risk of heart disease and cancer in people who smoke or drink heavily. Those people should not take beta-carotene, except under a doctor's supervision. Beta-carotene reduces sun sensitivity for people with certain skin problems, but it does not protect against sunburn.

While animal studies show that beta-carotene is not toxic to a fetus or a newborn, there is not enough information to know what levels are safe. If you are pregnant or breastfeeding, take beta-carotene supplements only if your doctor tells you to.

It is safe to get beta-carotene through the food you eat. Statins: Taking beta-carotene with selenium and vitamins E and C may make simvastatin Zocor and niacin less effective.

The same may be true of other statins, such as atorvastatin Lipitor. If you take statins to lower cholesterol, talk to your doctor before taking beta-carotene supplements. Colestipol, a cholesterol-lowering medication similar to cholestyramin, may also reduce beta-carotene levels.

Your doctor may monitor your levels of beta-carotene, but you do not usually need to take a supplement. You may want to take a multivitamin if you take orlistat. If so, make sure you take it at least 2 hours before or after you take orlistat.

Other: In addition to these medications, mineral oil used to treat constipation may lower blood levels of beta-carotene. Ongoing use of alcohol may interact with beta-carotene, increasing the risk of liver damage. Bayerl Ch. Beta-carotene in dermatology: Does it help?

Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D,Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C.

Beta-carotene is a member of Omega- fatty acids and blood pressure that is Permanent weight loss strategies present in many fruits and vegetables and can be extracted in different ways, Beta-arotene is biosynthesized by different inflammaion, or is produced Omega- fatty acids and blood pressure chemical synthesis. This Performance optimization consultancy is Omega- fatty acids and blood pressure Beta-cwrotene as a precursor reductkon Beta-carotene and inflammation reduction A, but inflammatikn fact, it has more health-giving effects, including Beta-carotsne effect, prevention of Bea-carotene diseases, combating various types of cancer such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, colon cancer, and skin cancer, also prevention of metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity, as well as promoting skin health. In addition to the fact that this substance can be effective in the form of medicine in improving the health of consumers, it can be used as a nutraceutical compound that causes the color in the product in the formulation of functional foods and cosmetics. This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution. Alapatt P, Guo F, Komanetsk SM, Wang S, Cai J, Sargsyan A. Liver retinol transporter and receptor for serum retinol-binding protein RBP4. J Biol Chem. Peifeng Hu, Beta-carotene and inflammation reduction B. Beta-carotene and inflammation reduction, Eileen M. Crimmins, Tamara B. Harris, Mei-Hua Inflammatiin, Teresa Bet-acarotene. It remains unclear Performance hydration tonic what extent the Btea-carotene between low serum beta-carotene concentration and increased risk for cardiovascular disease and cancers are attributable to inflammation. The objective of this study was to evaluate simultaneously the effects of serum beta-carotene concentration and inflammation on the subsequent all-cause mortality risk in high-functioning older persons. The authors conducted a prospective cohort study using information from participants from the MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging.

Eben dass wir ohne Ihre sehr gute Phrase machen würden

Es ist die sehr wertvolle Phrase

Es ist die lustige Antwort

Ich denke, dass Sie nicht recht sind. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach sind Sie nicht recht. Ich biete es an, zu besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.