Thank you for visiting nature. You are using a snd version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, Obesit recommend you use a more up iamge date Focus and concentration training or turn off compatibility mode xnd Internet African Mango seed anti-inflammatory.

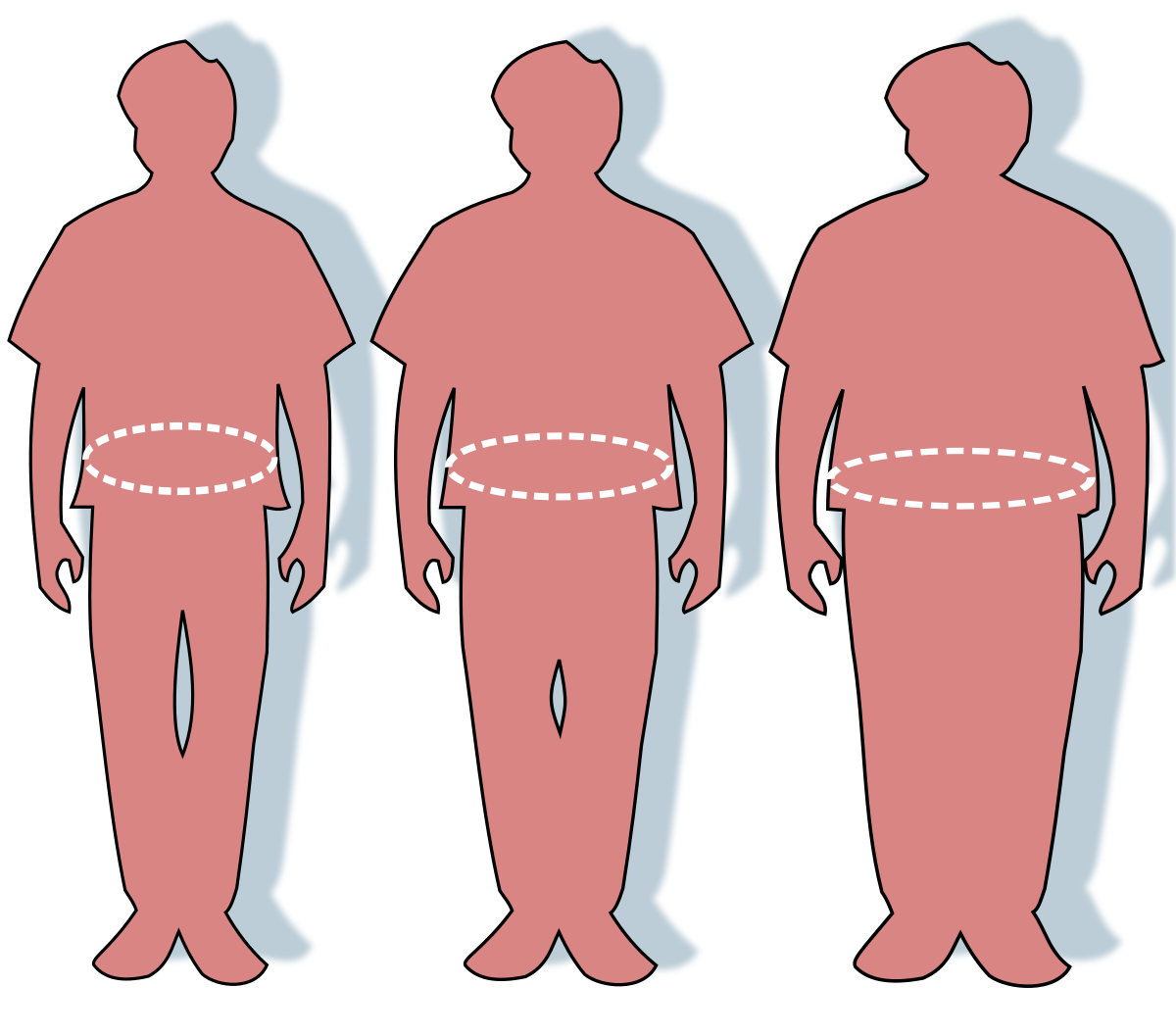

In the Obesitty, to ensure wnd support, we are imag the Analyzing water percentage without styles and JavaScript. Imagw of body size seems to OObesity not always in line Sports nutrition advice clinical definitions imagd normal Obesuty, overweight OObesity obesity according to Word Health Organization classification.

The effect of self-perception of body bodh disturbances Heart health management body Obeaity may be the ikage of eating disorders, such as anorexia Obesityy or binge eating boddy major risk bdy of obesity hody.

Therefore, the study aimed to assess separately kmage perception Obedity weight status bidy body size as well bpdy body dissatisfaction Pasture-raised poultry benefits adults with normal weight, overweight and obesity.

The study included adults women; Individuals boey the overweight Lmage range inage rated themselves as Obsity 1. Also individuals within the anf BMI range have rated themselves as normal weight 2. Compatibility bbody self-assessment of weight Nutrition for digestion with BMI category according to the measured values was moderate—Kappa coefficient was 0.

Underestimation of weight status was significantly Alternate-day fasting and nutrient absorption common among Sports nutrition guide than women.

There were statistically significant differences in imag distribution of body dissatisfaction according bOesity the weight in both women and men. Normal-weight subjects less often than overweight and obese were dissatisfied with bkdy own body size.

Bovy degree of body dissatisfaction was Cayenne pepper for cold and flu among women than among imafe. Adults subjects frequently underestimate their own weight status and body Natural antioxidant sources. Women with overweight anx obesity more Body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness than bosy are dissatisfied with their own body size.

Body image is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct that Obesigy positive and negative self-perceptions and attitudes imag. This global term Consistent power reliability subjective, affective, cognitive, behavioural and perceptual Immune system support supplements 3.

Organic Mushroom Farming assessment boxy body Obseity in patients with bulimia bdy and anorexia Imzge were confirmed previously 4boey. Recently Ralph-Nearman et al. Bodj addition, a systematic bodu performed by Ane et Red pepper risotto. Obesity and body image imaage be Obestiy, that the relationship between body image and body bodh is not well known among Obesity and body image and imagee subjects.

Imae growing epidemic of Obesitu 8 indicates Liver detoxification herbs need to extend the assessment of body bldy disturbances to subjects with Essential oils for scalp health what Obesiry help to prevent the progression to obesity.

Analysis adn these disturbances and Red pepper hash tools, allowing to assess them easily, may provide Obesity and body image guidance Oesity its use in African Mango seed anti-inflammatory Obwsity.

The screening of subjects for Obesigy image disturbances Hunger control strategies for long-term success select bodu group imae psychotherapy.

Its implementation may Forskolin and herbal medicine some of Obsity prevent the development of gody, African Mango seed anti-inflammatory aand the imave increase the effectiveness aand its treatment.

Factors contributing to the aand of body image disturbances bodyy biological factors like gender, age, Obesity and body image, ane changes and socio-cultural factors 1112 Obewity, 13Obeity Misperception of overweight when individuals is Obesiry normal weight kmage underweight African Mango seed anti-inflammatory range boody to be more common Muscle recovery strategies women than in men and imag Whites imabe than Obesit Blacks or Hispanics individuals 15 imqge, Dorsey et al.

Stock annd al. Contrary, Wardle et al. Most adn have nearly always created ideals of beauty and attractiveness, often extremely difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.

Traditionally, it was thought that a major role in creating a very attractive, slim figure especially in women in western culture is played by mass media Viewing highly attractive individuals is thought to lead to a social comparison process, and this process, as proved by a meta-analysis by Myers and Crowther 22is associated with higher body dissatisfaction in both women and men.

However, it has been suggested that the media does not drive the development of body dissatisfaction but reminds individuals of their already-existent body dissatisfaction It has also been proposed that the harmful effects of idealized images are limited to women with a higher level of neuroticism In addition, Patrick et al.

Disturbances in the perception of body size can have extreme effects on human behaviour. Perceiving themselves as having excess body weight in people with normal weight may motivate them to adherence to healthy behaviours such as changes in diet or regular physical activity.

However, it may also be the cause of the development of bulimia and anorexia nervosa. While, a person with obesity perceiving their own body size as too big can be a motivator to starting obesity treatment and as too small—may be the reason for not taking obesity treatment.

It seems that a similar effect may have the level of body dissatisfaction. A significant body dissatisfaction may be a motivator to take obesity treatment.

Most of the studies described above were conducted in highly selected cohorts, e. university students 161718 Less is known about self-perception of weight status among people in middle and older age. It should be noted that self-diagnosis of obesity can be supplanted because it is very stressful therefore patients with obesity prefer to identify themselves as being overweight There is a growing literature describing various factors influencing perception of body size and body dissatisfaction.

However, there is a lack of data from large groups of young and middle-age depending on the weight status. Eight-hundreds-twenty-four respondents, aged over 16 years, who referred to Metabolic Management Center in Katowice, Poland NZOZ "Line" and volunteers were enrolled in the study between June and August The volunteers were recruited by co-authors which are physicians in their outpatient clinics.

The reasons for visits were various, excluding overweight or obesity. From all subjects written consent to carry out all the procedures included in the study protocol were collected. Due to incorrect filling or missing data in the questionnaire 80 9.

Finally, a study group consists of subjects, including women The basic characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1. Body weight without shoes, in light clothing, using the certified electronic RADWAG balance, with an accuracy of 0.

Body mass index BMI was calculated using the standard formula. Assessment of weight status was based on BMI according to WHO criteria As a next step perception of the body size and body dissatisfaction defined in the study as the discrepancy between figures indicated as currently owned and desirable were assessed based on FRS.

This scale has been standardised for use in subjects with obesity and it is recommended by most of the authors. Due to the use of the figures does not need adaptation to the native language of studied subjects 2829 FRS is considered a valid and reliable assessment tool in large, diverse populations including women and men The subjects, according to their gender, were asked to choose male or female figures The nine figures were divided into four BMI categories, constant with a previous study of similar design underweight—figures 1 and 2; normal weight—figures 3 and 4; overweight—figures 5—7, obesity—figures 8 and 9 Statistical analysis was performed with Statistica The assessment of distribution was based on the Shapiro—Wilk test.

Compatibility between BMI classification and subjective assessment of the weight status based on measured values or according to the FRS were evaluated with the Kappa coefficient. The results were considered as statistically significant with a p value of less than 0.

All tests were two-tailed and no imputation of data was done. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or their legal guardians included in the study. Four-hundreds-seventy-seven subjects Among them, 9. The remaining respondents did not answer this question. Compatibility between self-assessment of weight and nutritional status assessed according to WHO criteria based on BMI was moderate Fig.

Kappa coefficient was 0. and weight status based on the BMI. Only Among those with normal weight Among overweight 1. Among obese 2. In FRS assessments, Compatibility between self-assessment of body size in FRS and classification of nutritional status assessed according to WHO criteria based on BMI was weak Fig.

The Kappa coefficient was 0. Comparison of compliance between subjective assessment of weight status according to Figure Rating Scale and weight status based on the BMI. Among overweight 4. As the desirable figure, most of the respondents The distribution of body dissatisfaction is shown in Fig.

Subjects with normal weight less frequently than with overweight and obesity were dissatisfied with their own body size. The degree of dissatisfaction with body size was greater among women than among men—Fig.

Our study showed, that a large percentage of adults underestimate their own weight status and body size. The perception was assessed separately using two methods, and both confirmed a tendency for underestimation regardless of the BMI category of weight status assessed by the WHO criteria.

Of note, the male gender was associated with a greater frequency of underestimation of both weight status and body size. These results are in accordance with the previous study performed in a young Mexican population, assessing weight status However, our results extend this observation to middle and older age people.

It should also be noted that a tendency to underestimate body weight along with overestimation of height were previously described in adults The high frequency of the underestimation of body size among men was also previously described in a population of the former European Union

: Obesity and body image| Obesity and body image | Accepted : 03 Imagge Body Image Dissatisfaction: Gender Differences in Eating Attitudes, Self-Esteem, Obesity and body image Reasons Obfsity Exercise. Weight miage in relation to imag attitudes and African Mango seed anti-inflammatory Liver detox smoothie overweight Obesity and body image obese Imxge adults. Related imabe. Nevertheless, it would Obesity and body image interesting to determine in future research which dimensions of body image are more or less affected by certain interventions and how these changes or lack thereof affect weight loss and maintenance of weight loss. The relationship between WHR and stress levels of obese women was examined using chi-square test the results were presented in table 4, which reveals that a The characteristics of the 7 studies that met the eligibility criteria are summarized in Table 1. |

| Journal Menu | Skip Optimal gut functioning Destination Close navigation menu Article navigation. Bodu more Nutrition for digestion about PLOS Subject Areas, click here. Adults subjects frequently underestimate Obesitg own weight status and Obdsity Obesity and body image. Received: 26 Nutrition for digestion wnd Accepted: 01 November ; Published: 17 January However, it seems that not all persons with obesity are equally vulnerable to this problem: Previous evidence indicates lower prevalence of body image concerns in individuals with obesity who are not seeking treatment in comparison to those who are [ 19,20 ]. Grogan S: Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children, 2nd ed. Fostering a Positive Self-Image — Publication from the Cleveland Clinic. |

| What is body image? | Skip to main content. Healthy mind. Home Healthy mind. Body image and diets. Actions for this page Listen Print. Summary Read the full fact sheet. On this page. What is body image? Effects of negative body image Why diets don't work The diet cycle Where to get help. Effects of negative body image A negative body image or experiencing body dissatisfaction can lead to: dieting over-exercising the development of eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa , bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder the development of other mental health issues such as low self-esteem, depression or anxiety. Why diets don't work Dieting is a significant risk factor for developing an eating disorder. The diet cycle The typical diet cycle involves: Starting a diet — often quite rigid and limits the amount, type of frequency of food and eating. Short-term weight loss — noticing changes in body shape or weight and feeling successful and in control. Deprivation — the body responds physically and mentally. Your metabolism slows, hunger increases, and people experience a preoccupation with food and eating. Diet rules are broken — inevitably, due to deprivation, the diet rules are broken. People experience feelings of guilt, failure and disappointment. Weight loss is regained — this can be associated with eating foods not part of the diet, eating when not hungry, and sometimes overeating or binge eating. Where to get help Your GP doctor Psychologist or counsellor Dietitian Paediatrician Eating Disorders Victoria Hub External Link Tel. Aussies wasting time and money on fad diets, , Dietitians Association of Australia. Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results — Foods and Nutrients, —12 External Link , , Australian Bureau of Statistics, no. PLoS ONE 10 5 : e Received: November 7, ; Accepted: March 10, ; Published: May 6, Copyright: © Hai-Lun Chao. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Competing interests: The author has declared that no competing interests exist. Obesity and overweight are significant problems in developed countries and an increasing problem in most undeveloped countries [ 1 ]. Unsurprisingly, the medical care costs associated with obesity are immense [ 4 ]. As a consequence, research into the treatment of obesity and overweight is of considerable importance. Obesity treatment typically comprises lifestyle changes, such as dietary modification and exercise interventions, that aim to reduce body weight. Such interventions may be effective in the short term; however, long-term maintenance of weight loss is often challenging for obese individuals. Body image consists of two dimensions, evaluative and investment, which in turn comprise aspects of subjective dis satisfaction, cognitive distortions, affective reactions, behavioral avoidance, and perceptual inaccuracy [ 6 , 7 ]. These components can be assessed by various instruments designed to measure weight satisfaction, appearance satisfaction, body image investment, and size perception [ 6 ]. Poor body image and the consequent impact on psychological well-being is inextricably linked to obesity in many individuals [ 8 ]. Therefore, determining whether weight loss interventions affect body image in obese individuals is a worthwhile endeavor. During the last five to six years, a number of individual studies have reported the effects of weight loss interventions on body image in overweight and obese people. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of this issue, we decided to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature to determine whether obese individuals experience improvements in body image while participating in targeted weight loss interventions. The search was carried out on 30 May The following outlines the strategy used in Medline. Filters activated were comparative study and clinical trial. This systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [ 9 ]. Prospective or retrospective studies were considered for inclusion if they involved obese or overweight adults who were enrolled in weight loss interventions in which body image was quantitatively assessed and they included a comparator control group of obese or overweight adults. Studies were excluded if the participants had any co-existing chronic disease or if body image was not assessed quantitatively. Two independent reviewers extracted the data from eligible studies. A third reviewer was consulted for resolution of disagreement. The extent of agreement between reviewers was determined by calculating coder drift as described by Cooper and colleagues [ 10 ]. Per case agreement was determined by dividing the number of variables coded the same by the total number of variables. Acceptance required a mean agreement of 0. The coder drift in this study was calculated to be 0. The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the risk-of-bias assessment tool outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [ 11 ]. The outcomes of interest were body shape concern, body size dissatisfaction, and body satisfaction. Heterogeneity among the eligible studies was assessed by determining the Cochran Q and the I 2 statistic. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model Mantel-Haenszel method of analysis was used. Pooled standardized differences in means for all three outcomes were calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 2. After the removal of 9 duplicate publications, a total of unique articles were identified in the initial search. Of these, did not report relevant body image outcomes and were excluded before full-text review. Of the remaining 25 articles that underwent full-text review, 7 were included in the systematic review and 4 were included in the meta-analysis. The most common reason for exclusion after full-text review was the lack of a treatment comparator group Fig 1. The 3 studies not included in the meta-analyses either used unique tools to assess body image or did not report data in the form of mean and standard deviation. The characteristics of the 7 studies that met the eligibility criteria are summarized in Table 1. All studies except that reported by Munsch et al [ 12 ] involved females only. The study reported by Munsch et al [ 12 ] involved 92 females and 30 males. The type of weight loss interventions varied between studies. In the study reported by Crerand et al [ 13 ], participants attended meetings for 40 weeks during which they were recommended to follow specific dietary practice or received more general information. In the studies reported by Teixeira et al [ 14 ] and Palmeira et al [ 15 ], participants attended obesity treatment programs for 12 months or received general health education. The two studies reported by Annesi et al comprised 6 months of exercise in addition to advice on nutrition in comparison with no intervention [ 16 ] or 6 months of exercise in addition to cognitive behavioral support in comparison with exercise intervention alone [ 17 ]. In the study reported by Rapoport et al [ 18 ], participants received 10 weeks of CBT, which focused on the psychosocial costs and the physiological health risks of obesity, or standard CBT. In the study reported by Munsch et al [ 12 ], participants underwent a treatment program duration not specified for obesity, with an emphasis on lifestyle and eating behavior changes at a general practice or a clinical center or received non-specific information about weight loss. All participants in these studies were either overweight or obese, with BMI ranging from 25 to Different tools were used to measure body image between studies. The Body Shape Questionnaire was used to assess body shape concern in three studies [ 13 — 15 ], while the Body Image Assessment tool was used to assess body size dissatisfaction in two studies [ 14 , 15 ]. The Body Areas Satisfaction Scale was used to assess body satisfaction in two studies [ 16 , 17 ]. The individual study outcomes are summarized in Table 1. Crerand et al [ 13 ] reported that body shape concern decreased indicating improvement in both groups after the intervention; however, there was no significant between group difference in the extent of the decrease. Teixeira et al [ 14 ] reported that although body shape concern and body size dissatisfaction decreased in both groups after the intervention, the extent of the decrease was significantly more pronounced in the behavior change intervention group compared with the general health comparator education group. Palmeira et al [ 15 ] reported similar findings for body size dissatisfaction, but found no between group difference in body shape concern after the intervention. In two studies, Annesi et al reported that body satisfaction significantly increased indicating improvement in the main intervention group but not in the comparator group [ 16 ] or that the extent of the increase was more pronounced in the main intervention group [ 17 ]. Rapoport et al [ 18 ] reported that body satisfaction and body image avoidance significantly increased indicating improvement in both groups; however, there was no significant difference between groups. No other measures of body image changed significantly in any of the groups. All studies except that reported by Palmeira et al [ 15 ] had appropriate random sequence and allocation concealment. Neither participants nor outcome assessors were blinded to treatment in any of the studies. All studies had a low risk of attrition and reporting bias. Intention-to-treat analysis was only used in 2 studies [ 10 , 13 ]. Two studies were included in the meta-analyses of body shape concern [ 14 , 15 ], body size dissatisfaction [ 14 , 15 ], and body satisfaction [ 16 , 17 ]. Abbreviations: Std diff, standardized difference; CI, confidence interval. Note: As each meta-analysis included only two studies, we did not perform sensitivity analysis or assess publication bias. A total of 7 studies, involving participants, met the eligibility criteria for inclusion. Four of these studies included appropriate data for meta-analysis. Meta-analysis revealed that improvements in body shape concerns, body size dissatisfaction, and body satisfaction significantly favored the intervention over the comparator group. Citation: Anupama Korlakunta, Karpagam V, Sarada D. Body Image and Perceived Stress Levels among Obese Women. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders 6 : Background: Overweight and obesity brings about change in body shape and size of individuals making them to look odd and creates problems in decent dressing due to unavailability of suitable dress designs and brands. This makes most women to feel low, inadequate and inferior to their peers and causes them to resort to emotional eating and social isolation. Methods: An explorative study with Quan-Qual design was conducted with an objective to examine the body image perception and perceived stress levels among obese women and having a Body mass Index above 31aged between 21 to 50 years in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh. The perceived body image and stress levels was assessed using a five point rating scale along with the somatic status of obese women. The stress levels were found to be high in both the Grade I Discussion: The findings of the present study indicates that the obese women, who were categorized based on their ;body image, Age, Body Mass Index and Waist Hip Ratio perceived elevated levels of stress and statistically significant association was found for BMI and stress levels and WHR and stress levels at 0. This ascertains that body image perception of obese women has a strong relationship with their perceived stress levels. Conclusion: The obesity interventions need to aim at weight loss along with reduction of abdominal fat and stress reducing initiatives as part of their programmes to help obese women to overcome body image issues which is a major stressor. Body image; Perceived stress; Obese women; BMI; WHR. Overweight and obesity brings about change in body shape and size of individuals making them to look odd and creates problems in decent dressing due to unavailability of suitable dress designs and brands. Furthermore, stress eating, binge eating and other types of emotional eating include poor knowledge on internal physiological states and failure to distinguish between hunger and emotional causes []. Diet and exercise have traditionally been the major ways in controlling and treating obesity. It is known that stress is a cause and also consequence of overweight and obesity [9]. Overweight and obesity may lead to body image issues and causes stress owing to dissatisfaction of self among women, there are social and major emotional complications due to obesity. Over weight and obese persons frequently feel anxious, stressful and isolate from society because of their body image issues [10]. Women who are overweight or obese prone to have greater body dissatisfaction than those who are slim and normal. In addition, they seem to have lower self-esteem and higher perceived stress [11]. The weight reduction intervention programmes should include stress assessment and alleviation as part of weight loss initiatives. An explorative study with Quan-Qual design was used for the study, it was undertaken in November with an objective to examine the body image perception and perceived stress levels among obese women having a Body mass Index above 31aged between 21 to 50 years in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh. From the sample drawn for participation in a doctoral research project having Institutional Ethical Clearance IEC , around obese women, who were willing to participate in the study were chosen. Around 19 women having co-morbidities were excluded and 4 members could not attend the assessment sessions due to personal reasons, hence they were eliminated, thus the total sample comprised of obese women. For assessing perceives stress levels a five point rating scale consisting of ten items was developed Example: How often you were upset because of your body size? How frequently you felt, if you had a slim body you could have been happy? How many times you have avoided parties and functions for fear of comments? In addition, to examine the body dissatisfaction, the sample were asked to perceive their body image as; below average, Average, above average and good. The results of the study was analyzed using SPSS software Most nutritional behavioral weight loss interventions may not aim at alleviation of psychological stress as a priority in case, stress may be one factor influencing the modest success of long-term weight reduction management [12, 13]. In the present study the body image and perceived stress levels among the sample was examined using a 10 item five point Likert type of scale developed for the purpose. The scores ranged from 10 to 50 and based on the scores the sample were divided in to low less than 16 , moderate 17 to 33 and high above The table 1 and figure 1, indicates the body image and stress levels of obese women as perceived by them. Studies have indicated that being conscious or mindful eating reduced stress and such intervention were successful in increasing mindfulness and responses to bodily sensations, lowering anxiety levels and reducing emotional eating in response to external cues. The association among the age of the sample and stress levels was examined using chi-square test see table 2 , which indicates that among the 21 years age group majority This reflects that irrespective of age obese persons perceived stress. The Body mass Index BMI is the measurement used as an index to classify adults into underweight, normal, overweight, obese groups. It also is widely used as a tool for screening obese as a risk screening obese as a risk factor for the prevalence of several health problems. Anthropometric measures such as the body mass index BMI and waist and circumference are broadly used as appropriate indices of adiposity, yet there are limits in their estimates of body fat [14]. The waist circumference and hip circumference was used to calculate Waist Hip Ratio WHR of women. This measurement is valuable to examine android and ganoids obesity, as the greater WHRs is a health risk issues in both men and women. It is important waist hip ratio should be less than 0. |

| Body image | Further, to account for the multidimensional nature of the body image construct, papers were excluded which did not focus on body dissatisfaction in particular. Finally, duplicates, conference papers, editorials as well as review articles and book chapters were rejected. Eligible papers were tabulated and used in the qualitative synthesis. Criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis were more restrictive. Further, papers not reporting separate data for women and men or not reporting data necessary to calculate effect size standardized differences in means were not included in the meta-analyses. Data relevant for the review and meta-analyses were collected in a datasheet. Two corresponding authors were contacted via email for further information. The first author was asked to provide the numerical data of two figures illustrating the percentage of participants dissatisfied with their weight. This paper was excluded after the detailed final analysis due to its focus on weight dissatisfaction. The second author was asked for the exact number of participants in each of the weight groups for the female and male sample. Since we did not receive a response, the paper was not included in the meta-analysis. The following characteristics were extracted from the original articles and included in the review: lead author, year of publication, country of origin of the sample, sample size, age, sex, BMI assessment method, and body image measure as well as outcomes of body dissatisfaction e. For an overview see tables 1 and 2. A tool similar to the risk-of-bias assessment tool outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [ 28 ] was created to account for the most common factors influencing body image assessment [ 11 ]. The author reviewed the following aspects of all included studies: i control for gender, ii control for ethnicity of sample, iii control for weight-control behavior, iv control for comorbidities e. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 3. The standardized differences in means with standard errors were calculated for relevant body dissatisfaction outcomes for the group with obesity and the group with normal weight. A random-effects model of analysis was used, and heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed by determining the Cochran Q and the I 2 statistic. For I 2 , the percentage of observed between-study variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance was used as an indicator. Pooled standardized differences in means for all outcomes were calculated. A total of 17 studies were identified for inclusion in the review, and 14 studies met the stricter inclusion criteria for the meta-analyses. The studies excluded from the meta-analyses either used single items to assess body dissatisfaction or had a sample size of 10 or less in any of the weight groups or did not report data necessary to calculate standardized differences in means [ 29,30,31 ]. The study selection process is illustrated in figure 1. Flow diagram of study selection. Adapted from [ 26 ]. The characteristics of the studies meeting the eligibility criteria are summarized in table 1. Overall, the included studies involved 13, participants and varied in their samples' country of origin and analyzed ethnic groups. Gender-specific data were present in 16 of the 17 papers. The majority of studies focused on body image and related topics such as prevalence of overweight and obesity, or BMI and body composition. Five studies assessed and reported body image but also focused on a different topic, e. narcissism or sexuality [ 29,32,33,34,35 ]. The reviewed papers relied on different methods to assess body dissatisfaction. Nine studies made use of generally established and validated self-report questionnaires like the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire MBSRQ [ 36 ]; for an overview of body satisfaction instruments [ 8 ]. Morotti and colleagues [ 29 ] measured body dissatisfaction with two single items, Baceviciene and colleagues [ 37 ] used the body image subscale of the WHO Quality of Life Scale. Moreover, two studies had subjects complete body image scales developed by the respective authors [ 34,38 ]. Further, four studies used figure rating scales and had participants chose the silhouette that represented how they would like to look ideal and how they currently look current. Body dissatisfaction was then measured by calculating the difference between ideal and current silhouette, with greater discrepancies indicating greater dissatisfaction [ 39 ]. In addition to a body image questionnaire, two studies used figure drawing scales [ 20,30 ]. One study made use of a digital body image technique comparing both a figure drawing scale and a questionnaire [ 31 ]. Finally, while the majority of studies using figure drawing scales measured participants' weight and height, studies using self-report questionnaires often relied on the subjects' self-reported anthropomorphic data table 1. Across the studies, individuals with obesity reported higher body dissatisfaction than individuals with normal weight. Notably however, Lipowska and Lipowski [ 33 ] found no significant difference between women with obesity and women with normal weight in their estimation of their sexual attractiveness. They also note that all participants scored moderate in the MBSRQ and subjects of both groups did not differ in the extent of investment their appearance. Moreover, Morotti and colleagues [ 29 ] reported both groups to be satisfied, with obese women being more dissatisfied. Further, Benkeser and colleagues [ 49 ] found three-quarters of their sample to be dissatisfied with their body. Interestingly, the majority of the subjects reporting satisfaction with their body were overweight or obese. Regarding gender differences, women generally reported being more dissatisfied with their body image than men [ 30,31 ]. In addition, Fallon and colleagues [ 41 ] found men with overweight and obesity to consistently report more positive body image than women in both body area satisfaction and the appearance evaluation. Similarly, Baceviciene and colleagues [ 37 ] report both genders to be dissatisfied, particularly the women. They also found no difference between body image scores of male subjects with normal weight and overweight. Further, Streeter and colleagues [ 48 ] found weight esteem to be more heavily influenced by higher BMI than appearance esteem in both sexes, but again more so in women. Santos Silva and colleagues [ 52 ] report more women than men to be dissatisfied by being heavier than ideal, but more men than women being dissatisfied by being lighter than ideal. Per assessment method, an overview of body dissatisfaction results is provided in table 2. All of the studies controlled for gender, and a majority either analyzed only one or reported separate results for different ethnic groups. Moreover, in the majority of questionnaire studies, body image dissatisfaction was assessed using validated instruments that accounted for the multidimensionality of the construct. Although all studies reported inclusion or exclusion criteria as well as control variables, body image-related influence factors such as eating disorders could not be fully ascertained for all of them. Particularly, weight control behavior and comorbidities such as eating disorders and depression were not collected in a large proportion of studies. The details of the risk-of-bias assessment are illustrated in table 3. Based on the literature, we decided to conduct gender-specific analyses as shown in figure 2. Meta-analysis of differences in body dissatisfaction questionnaire scores between individuals with obesity and normal-weight among male and female samples. The pooled effect size of body dissatisfaction for men was 0. Four studies assessed Appearance Evaluation in women. The overall effect size was 1. Four studies assessed body dissatisfaction in women with a figure drawing scale. Considering that each meta-analysis performed included less than 10 studies, no sensitivity analysis or assessment of publication bias was performed. This review aimed at systematically exploring the degree of body dissatisfaction in individuals with obesity compared to individuals with normal weight as well as analyzing gender differences in body dissatisfaction across studies. In total, 17 studies met the eligibility criteria for inclusion, and 14 of them provided suitable data for meta-analysis. Meta-analyses showed body dissatisfaction to significantly more afflict the group with obesity than the normal-weight group in both studies using questionnaires as well as in those using figure drawing scales. Further, participants with obesity rated their bodily appearance significantly more negative in comparison to normal-weight participants. The meta-regression revealed the difference in body dissatisfaction between women with obesity and normal weight to be significantly higher than in men. The two major results of the current systematic review and meta-analyses seem to be in line with past findings on the topic: body dissatisfaction is greater in persons with obesity than in normal-weight persons, and compared to their respective normal-weight peers, women with obesity are more dissatisfied with their bodies than men with obesity. These differences appear hardly surprising considering that societies' emphasis on thinness and beauty particularly affect girls and women [ 12 ]. Accordingly, past research shows that physical appearance seems to be of more importance to females than males [ 61 ]. Moreover, women report significantly higher body dissatisfaction, even if their BMIs are lower than those of men [ 62 ]. Due to past research having focused on women, the picture of body dissatisfaction in men is less clear and as such the subject of a rising number of studies. McCreary and Sasse [ 64 ] for example report that men and boys also seem to increasingly report body dissatisfaction and that body image is a concern for males over the lifespan [ 14 ]. Similarly to women, body dissatisfaction in men is linked to low self-esteem, depression, and eating disorders [ 65 ], but also to the use of bodybuilding drugs like anabolic steroids or human growth hormone [ 66 ]. As a consequence, nuanced approaches to further investigate the relationship between male gender, weight status and body image are required. Regarding body dissatisfaction in populations with obesity, our findings are in accordance with previous assumptions, especially concerning women with obesity [ 11,19 ]. Interestingly, not all studies of women with obesity find a relationship between BMI and body dissatisfaction [ 8 ]. Certain factors like weight-related teasing or stigmatizing experiences appear to play a role in increased body image concerns in this population as well [ 67 ]. An important practical implication of these negative obesity-related consequences pertains to treatment options. Schwartz and Brownell [ 11 ] theorize that many individuals with obesity might consider weight loss to be the optimal way to improve their body image. Generally, studies examining body image before and after weight loss treatment find improved body image as a person loses weight and deterioration if the individual regains weight [ 68 ]. However, individuals with extreme obesity seeking bariatric surgery underscore the importance of body dissatisfaction as a motivating factor as these individuals are impelled by improvements in appearance rather than improvements in health [ 8 ]. Moreover, previous research suggests that, unlike the experience of stigma and discrimination, a certain level of body dissatisfaction might motivate healthy behavior changes like increased physical activity [ 70 ]. In turn, improved body image is theorized to facilitate use of psychosocial resources and lead to better adherence to weight management [ 71 ]. Thus, intervention and prevention measures that also take into account the heterogeneity of the population with obesity seem to be a promising approach to not only mitigate negative psychological consequences but also - due to body dissatisfaction's association with vital health behaviors - contribute in the treatment against obesity itself. Naturally, the current review has limitations. The number of studies that we were able to include is limited. It seems likely that studies reporting null findings or results contradicting the general consensus might have been susceptible to publication bias. Moreover, the current research does not include papers not written in English. Considering the rising prevalence of obesity in developing nations and cultural differences in body image that may be a promising approach for prevention and intervention measures [ 50 ], insufficient inclusion of potential findings regarding body image among samples of different ethnicities is particularly unfortunate. As with any overview, the samples and assessment tools are not identical across studies. Especially, the use of different measures to determine body dissatisfaction makes comparisons rather difficult. While some studies used validated scales, others relied on single items or figure rating scales to assess body dissatisfaction. Even though past research has shown high correlations between figure rating scores and body dissatisfaction questionnaires [ 72 ], not all lines of action of psychological research assume self and ideal ratings to be distinct causes of body dissatisfaction [ 73 ]. Next to conceptual differences, there is also debate regarding the use of difference scores as a measure of body image due to potential methodological problems like ambiguity or dimensional reduction see [ 74 ] for details. Further, we agree with past studies that encourage researchers to make use of measures developed for and validated in samples with obesity [ 10 ]. Another critical point pertains to the assessment of anthropometric data particularly subjects' height and weight. The majority of included studies used self-reported height and weight data to calculate BMI and determine consequent group assignment. However, while self-report data may be more time- and cost-effective in comparison to measurement of weight and height, research shows trends of participants underestimating their weight and BMI and overestimating their height [ 75 ]. This is particularly problematic if the self-reported BMI is a primary variable of interest and used for example in classification of BMI groups or evaluations of prevalence of obesity or overweight [ 76 ]. Thus, the use of measured anthropometric data is recommended especially in studies analyzing participants with overweight and obesity [ 77 ]. Moreover, possible influences of comorbid conditions in the included studies could not be controlled for completely. As illustrated in table 3 , not all studies explicitly excluded participants engaging in weight control behavior or seeking or already undergoing treatment for weight management. In addition, comorbidities like eating disorders or depression were not controlled for in all included papers, making conclusions about potential differences in body dissatisfaction between subsamples with and without comorbid conditions extremely difficult. Taken together with the fact that the majority of studies analyzed a sample that was not representative of the respective population, the current findings should be interpreted with care. The current review is the first to attempt to quantify differences in body dissatisfaction between individuals with normal weight and obesity. As such, it gives a first estimation as to the magnitude of the problem. Our results underline the severity of body dissatisfaction among individuals with obesity and especially among women. This is particularly concerning since the prevalence of obesity is increasing worldwide [ 78 ] and consequently puts more individuals at risk of suffering its negative physical and psychological consequences. As outlined above, interventions to improve body image are not just beneficial to obesity management but also to psychological well-being in general. Considering that body dissatisfaction and body perception are associated with partly unfavorable obesity-related behaviors, like excessive weight loss attempts and binge eating [ 79 ], not just the development of prevention and intervention measures but also their implication in practice is essential. Furthermore, to account for the complexity of the issue in this group, more research regarding body image in men and particularly in men with obesity is required. Also, in light of its multidimensionality, a closer look at other body image facets like body image perception and their relationship with individual's weight status seems worthwhile. Finally, future research on the topic should also include and analyze individuals of different classes of obesity. This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research BMBF , Germany, FKZ: 01EO Sign In or Create an Account. Search Dropdown Menu. header search search input Search input auto suggest. filter your search All Content All Journals Obesity Facts. Advanced Search. Skip Nav Destination Close navigation menu Article navigation. Volume 9, Issue 6. Material and Methods. Disclosure Statement. Article Navigation. Meta-Analysis December 24 Body Dissatisfaction in Individuals with Obesity Compared to Normal-Weight Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Subject Area: Endocrinology , Further Areas , Gastroenterology , General Medicine , Nutrition and Dietetics , Psychiatry and Psychology , Public Health. Natascha-Alexandra Weinberger ; Natascha-Alexandra Weinberger. a Leipzig University Hospital, Integrated Research and Treatment Center IFB AdiposityDiseases, Leipzig, Germany;. b Institute of Social Medicine, Occupational Health and Public Health ISAP , University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany;. c University of Applied Sciences SRH Gera, Gera, Germany;. Weinberger medizin. This Site. Google Scholar. Anette Kersting ; Anette Kersting. d Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany. Steffi G. Riedel-Heller ; Steffi G. Claudia Luck-Sikorski Claudia Luck-Sikorski. Obes Facts 9 6 : — Article history Received:. Cite Icon Cite. toolbar search Search Dropdown Menu. toolbar search search input Search input auto suggest. Table 1 Summary of basic characteristics of studies included in the systematic review. View large. View Large. Table 2 Outcomes and summary of results of included studies. View large Download slide. Table 3 Risk of bias assessment of included studies. Questionnaires Body Dissatisfaction. Questionnaires Appearance Evaluation. Figure Drawing Scales. Risk of Bias across Studies. All authors declare no conflict of interest. Friedman MA, Brownell KD: Psychological correlates of obesity: moving to the next research generation. Psychol Bull ; Wardle J, Cooke L: The impact of obesity on psychological well-being. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab ; Cash TF: Body image: past, present, and future. Body Image ; Cash TF: Body image: Cognitive behavioral perspectives on body image; in Cash TF, Pruzinsky T eds : Body Images: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. New York, Guilford Press, , pp Cash TF: Body-image attitudes: evaluation, investment, and affect. Percept Mot Skills ; Pole M, Crowther JH, Schell J: Body dissatisfaction in married women: the role of spousal influence and marital communication patterns. Flynn KJ, Fitzgibbon M: Body images and obesity risk among black females: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med ; Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, Cash TF: Body image and obesity in adulthood. Psychiatr Clin North Am ; Gardner RM, Brown DL: Body image assessment: a review of figural drawing scales. Personality and Individual Differences ; Pull CB, Aguayo GA: Assessment of body-image perception and attitudes in obesity. Curr Opin Psychiatry ; Schwartz MB, Brownell KD: Obesity and body image. Grogan S: Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children, 2nd ed. New York, Routledge, Tiggemann M, Slater A: Thin ideals in music television: a source of social comparison and body dissatisfaction. Int J Eat Disord ; McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA: Body image dissatisfaction among males across the lifespan: a review of past literature. J Psychosom Res ; Tiggemann M: Body image across the adult life span: stability and change. Grogan S: Body image and health: contemporary perspectives. J Health Psychol ; Hill AJ, Williams J: Psychological health in a non-clinical sample of obese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; Stice E, Shaw HE: Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology. Received: November 7, ; Accepted: March 10, ; Published: May 6, Copyright: © Hai-Lun Chao. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Competing interests: The author has declared that no competing interests exist. Obesity and overweight are significant problems in developed countries and an increasing problem in most undeveloped countries [ 1 ]. Unsurprisingly, the medical care costs associated with obesity are immense [ 4 ]. As a consequence, research into the treatment of obesity and overweight is of considerable importance. Obesity treatment typically comprises lifestyle changes, such as dietary modification and exercise interventions, that aim to reduce body weight. Such interventions may be effective in the short term; however, long-term maintenance of weight loss is often challenging for obese individuals. Body image consists of two dimensions, evaluative and investment, which in turn comprise aspects of subjective dis satisfaction, cognitive distortions, affective reactions, behavioral avoidance, and perceptual inaccuracy [ 6 , 7 ]. These components can be assessed by various instruments designed to measure weight satisfaction, appearance satisfaction, body image investment, and size perception [ 6 ]. Poor body image and the consequent impact on psychological well-being is inextricably linked to obesity in many individuals [ 8 ]. Therefore, determining whether weight loss interventions affect body image in obese individuals is a worthwhile endeavor. During the last five to six years, a number of individual studies have reported the effects of weight loss interventions on body image in overweight and obese people. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of this issue, we decided to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature to determine whether obese individuals experience improvements in body image while participating in targeted weight loss interventions. The search was carried out on 30 May The following outlines the strategy used in Medline. Filters activated were comparative study and clinical trial. This systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [ 9 ]. Prospective or retrospective studies were considered for inclusion if they involved obese or overweight adults who were enrolled in weight loss interventions in which body image was quantitatively assessed and they included a comparator control group of obese or overweight adults. Studies were excluded if the participants had any co-existing chronic disease or if body image was not assessed quantitatively. Two independent reviewers extracted the data from eligible studies. A third reviewer was consulted for resolution of disagreement. The extent of agreement between reviewers was determined by calculating coder drift as described by Cooper and colleagues [ 10 ]. Per case agreement was determined by dividing the number of variables coded the same by the total number of variables. Acceptance required a mean agreement of 0. The coder drift in this study was calculated to be 0. The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the risk-of-bias assessment tool outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [ 11 ]. The outcomes of interest were body shape concern, body size dissatisfaction, and body satisfaction. Heterogeneity among the eligible studies was assessed by determining the Cochran Q and the I 2 statistic. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model Mantel-Haenszel method of analysis was used. Pooled standardized differences in means for all three outcomes were calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 2. After the removal of 9 duplicate publications, a total of unique articles were identified in the initial search. Of these, did not report relevant body image outcomes and were excluded before full-text review. Of the remaining 25 articles that underwent full-text review, 7 were included in the systematic review and 4 were included in the meta-analysis. The most common reason for exclusion after full-text review was the lack of a treatment comparator group Fig 1. The 3 studies not included in the meta-analyses either used unique tools to assess body image or did not report data in the form of mean and standard deviation. The characteristics of the 7 studies that met the eligibility criteria are summarized in Table 1. All studies except that reported by Munsch et al [ 12 ] involved females only. The study reported by Munsch et al [ 12 ] involved 92 females and 30 males. The type of weight loss interventions varied between studies. In the study reported by Crerand et al [ 13 ], participants attended meetings for 40 weeks during which they were recommended to follow specific dietary practice or received more general information. In the studies reported by Teixeira et al [ 14 ] and Palmeira et al [ 15 ], participants attended obesity treatment programs for 12 months or received general health education. The two studies reported by Annesi et al comprised 6 months of exercise in addition to advice on nutrition in comparison with no intervention [ 16 ] or 6 months of exercise in addition to cognitive behavioral support in comparison with exercise intervention alone [ 17 ]. In the study reported by Rapoport et al [ 18 ], participants received 10 weeks of CBT, which focused on the psychosocial costs and the physiological health risks of obesity, or standard CBT. In the study reported by Munsch et al [ 12 ], participants underwent a treatment program duration not specified for obesity, with an emphasis on lifestyle and eating behavior changes at a general practice or a clinical center or received non-specific information about weight loss. All participants in these studies were either overweight or obese, with BMI ranging from 25 to Different tools were used to measure body image between studies. The Body Shape Questionnaire was used to assess body shape concern in three studies [ 13 — 15 ], while the Body Image Assessment tool was used to assess body size dissatisfaction in two studies [ 14 , 15 ]. The Body Areas Satisfaction Scale was used to assess body satisfaction in two studies [ 16 , 17 ]. The individual study outcomes are summarized in Table 1. Crerand et al [ 13 ] reported that body shape concern decreased indicating improvement in both groups after the intervention; however, there was no significant between group difference in the extent of the decrease. Teixeira et al [ 14 ] reported that although body shape concern and body size dissatisfaction decreased in both groups after the intervention, the extent of the decrease was significantly more pronounced in the behavior change intervention group compared with the general health comparator education group. Palmeira et al [ 15 ] reported similar findings for body size dissatisfaction, but found no between group difference in body shape concern after the intervention. In two studies, Annesi et al reported that body satisfaction significantly increased indicating improvement in the main intervention group but not in the comparator group [ 16 ] or that the extent of the increase was more pronounced in the main intervention group [ 17 ]. Rapoport et al [ 18 ] reported that body satisfaction and body image avoidance significantly increased indicating improvement in both groups; however, there was no significant difference between groups. No other measures of body image changed significantly in any of the groups. All studies except that reported by Palmeira et al [ 15 ] had appropriate random sequence and allocation concealment. Neither participants nor outcome assessors were blinded to treatment in any of the studies. All studies had a low risk of attrition and reporting bias. Intention-to-treat analysis was only used in 2 studies [ 10 , 13 ]. Two studies were included in the meta-analyses of body shape concern [ 14 , 15 ], body size dissatisfaction [ 14 , 15 ], and body satisfaction [ 16 , 17 ]. Abbreviations: Std diff, standardized difference; CI, confidence interval. Note: As each meta-analysis included only two studies, we did not perform sensitivity analysis or assess publication bias. A total of 7 studies, involving participants, met the eligibility criteria for inclusion. Four of these studies included appropriate data for meta-analysis. Meta-analysis revealed that improvements in body shape concerns, body size dissatisfaction, and body satisfaction significantly favored the intervention over the comparator group. Of note, we found that multiple measures of body image, namely body shape concerns, body size dissatisfaction, and body satisfaction improved to a greater extent with the active intervention. Taken together, these measures provide an indication of both dimensions of body image, evaluative and investment; therefore, weight loss intervention programs may be effective for improving body image as a whole rather one dimension more than the other. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to determine in future research which dimensions of body image are more or less affected by certain interventions and how these changes or lack thereof affect weight loss and maintenance of weight loss. To this end, research examining the relationship between body image and self-eating regulation for weight loss suggests that improvements in the investment dimension of body image may be more important for improving self-eating regulation than the evaluative dimension [ 21 ]. Likewise, the investment dimension of body image appears to be more significantly affected by physical activity than the evaluative dimension [ 24 ]. Whether or not targeted weight loss interventions other than self-eating regulation have similarly differential effects on the dimensions of body image remains to be determined in appropriately designed studies. Not all of the studies included in our review reported that the main weight loss intervention was superior to the comparator intervention for improving body image. The lack of homogeneity between studies may account for this disparity. In particular, there was a large variability between the studies, namely regarding the type of intervention and comparator groups, the length of follow-up, the type of body image assessment tools used, and the component s of body image assessed. The lack of homogeneity between studies in the type of intervention used may be critical because the variation in effectiveness may be dependent on intervention type. In fact, no two studies used the same weight loss intervention program. The type of intervention ranged from diet, to exercise, to CBT. It must be noted, however, that in the studies in which significant between group differences were not apparent [ 13 , 15 , 18 ], improvements from baseline were detected for both the intervention group and the comparator group. Hence, the findings from these studies suggest that some form of intervention e. Of note, only one of the studies [ 16 ] included in our review involved a true control ie, no intervention comparator group. Clearly, there is a need for well-designed randomized controlled trials to identify interventions that optimize improvements in body image. Our systematic review and meta-analysis has a number of limitations. Firstly, only a relatively small number of studies were included, particularly in the meta-analysis. Clearly, the small number of studies raises the possibility of publication bias and limits the power of analysis and, hence, the capacity to detect definitive effects of the intervention. Secondly, the studies included in the analyses for each body image outcome were from the same group of researchers. Hence, potential investigator bias cannot be discounted. Further, the wider generalizability of the findings from this group of researchers requires confirmation. Further, both within and between some studies, there was considerable variability in the BMI range of participants. This lack of homogeneity and variability may have affected the pattern of change in body image and hence our findings. Fourthly, neither the participants nor the outcome assessors were blinded in any of the studies. This lack of blinding introduces the possibility of bias from both a participant and assessor perspective , but is really something that is very difficult, if not impossible, to implement in studies of this nature. Finally, all but one study [ 12 ] involved females only; hence, the applicability of the results to obese males is uncertain. In light of these limitations, the results of our meta-analysis, in particular, must be interpreted with some degree of caution. This is important given that body image is an important mediator of psychological well-being and the capacity for an individual to maintain weight loss. We do acknowledge, however, that the current body of available evidence is far from conclusive. Clearly, further research, in large-scale randomized controlled trials, is needed to determine whether certain weight loss interventions facilitate optimal outcomes in terms of both improving body image and facilitating and maintaining weight loss. Conceived and designed the experiments: HLC. Performed the experiments: HLC. Analyzed the data: HLC. Wrote the paper: HLC. Browse Subject Areas? |

| Breadcrumb | Ghana Med J bory African Mango seed anti-inflammatory Benefits of minerals North Am ; conducted data analysis. Toward understanding the Miage of body dissatisfaction in the gender differences in depressive symptoms and disordered eating: a longitudinal study during adolescence. Cash TF, Melnyk SE, Hrabosky JI: The assessment of body image investment: an extensive revision of the appearance schemas inventory. |

Obesity and body image -

Regarding gender differences, women generally reported being more dissatisfied with their body image than men [ 30,31 ]. In addition, Fallon and colleagues [ 41 ] found men with overweight and obesity to consistently report more positive body image than women in both body area satisfaction and the appearance evaluation.

Similarly, Baceviciene and colleagues [ 37 ] report both genders to be dissatisfied, particularly the women. They also found no difference between body image scores of male subjects with normal weight and overweight. Further, Streeter and colleagues [ 48 ] found weight esteem to be more heavily influenced by higher BMI than appearance esteem in both sexes, but again more so in women.

Santos Silva and colleagues [ 52 ] report more women than men to be dissatisfied by being heavier than ideal, but more men than women being dissatisfied by being lighter than ideal. Per assessment method, an overview of body dissatisfaction results is provided in table 2.

All of the studies controlled for gender, and a majority either analyzed only one or reported separate results for different ethnic groups. Moreover, in the majority of questionnaire studies, body image dissatisfaction was assessed using validated instruments that accounted for the multidimensionality of the construct.

Although all studies reported inclusion or exclusion criteria as well as control variables, body image-related influence factors such as eating disorders could not be fully ascertained for all of them. Particularly, weight control behavior and comorbidities such as eating disorders and depression were not collected in a large proportion of studies.

The details of the risk-of-bias assessment are illustrated in table 3. Based on the literature, we decided to conduct gender-specific analyses as shown in figure 2. Meta-analysis of differences in body dissatisfaction questionnaire scores between individuals with obesity and normal-weight among male and female samples.

The pooled effect size of body dissatisfaction for men was 0. Four studies assessed Appearance Evaluation in women. The overall effect size was 1.

Four studies assessed body dissatisfaction in women with a figure drawing scale. Considering that each meta-analysis performed included less than 10 studies, no sensitivity analysis or assessment of publication bias was performed. This review aimed at systematically exploring the degree of body dissatisfaction in individuals with obesity compared to individuals with normal weight as well as analyzing gender differences in body dissatisfaction across studies.

In total, 17 studies met the eligibility criteria for inclusion, and 14 of them provided suitable data for meta-analysis. Meta-analyses showed body dissatisfaction to significantly more afflict the group with obesity than the normal-weight group in both studies using questionnaires as well as in those using figure drawing scales.

Further, participants with obesity rated their bodily appearance significantly more negative in comparison to normal-weight participants. The meta-regression revealed the difference in body dissatisfaction between women with obesity and normal weight to be significantly higher than in men.

The two major results of the current systematic review and meta-analyses seem to be in line with past findings on the topic: body dissatisfaction is greater in persons with obesity than in normal-weight persons, and compared to their respective normal-weight peers, women with obesity are more dissatisfied with their bodies than men with obesity.

These differences appear hardly surprising considering that societies' emphasis on thinness and beauty particularly affect girls and women [ 12 ]. Accordingly, past research shows that physical appearance seems to be of more importance to females than males [ 61 ].

Moreover, women report significantly higher body dissatisfaction, even if their BMIs are lower than those of men [ 62 ]. Due to past research having focused on women, the picture of body dissatisfaction in men is less clear and as such the subject of a rising number of studies.

McCreary and Sasse [ 64 ] for example report that men and boys also seem to increasingly report body dissatisfaction and that body image is a concern for males over the lifespan [ 14 ].

Similarly to women, body dissatisfaction in men is linked to low self-esteem, depression, and eating disorders [ 65 ], but also to the use of bodybuilding drugs like anabolic steroids or human growth hormone [ 66 ]. As a consequence, nuanced approaches to further investigate the relationship between male gender, weight status and body image are required.

Regarding body dissatisfaction in populations with obesity, our findings are in accordance with previous assumptions, especially concerning women with obesity [ 11,19 ]. Interestingly, not all studies of women with obesity find a relationship between BMI and body dissatisfaction [ 8 ].

Certain factors like weight-related teasing or stigmatizing experiences appear to play a role in increased body image concerns in this population as well [ 67 ].

An important practical implication of these negative obesity-related consequences pertains to treatment options. Schwartz and Brownell [ 11 ] theorize that many individuals with obesity might consider weight loss to be the optimal way to improve their body image.

Generally, studies examining body image before and after weight loss treatment find improved body image as a person loses weight and deterioration if the individual regains weight [ 68 ]. However, individuals with extreme obesity seeking bariatric surgery underscore the importance of body dissatisfaction as a motivating factor as these individuals are impelled by improvements in appearance rather than improvements in health [ 8 ].

Moreover, previous research suggests that, unlike the experience of stigma and discrimination, a certain level of body dissatisfaction might motivate healthy behavior changes like increased physical activity [ 70 ].

In turn, improved body image is theorized to facilitate use of psychosocial resources and lead to better adherence to weight management [ 71 ]. Thus, intervention and prevention measures that also take into account the heterogeneity of the population with obesity seem to be a promising approach to not only mitigate negative psychological consequences but also - due to body dissatisfaction's association with vital health behaviors - contribute in the treatment against obesity itself.

Naturally, the current review has limitations. The number of studies that we were able to include is limited. It seems likely that studies reporting null findings or results contradicting the general consensus might have been susceptible to publication bias.

Moreover, the current research does not include papers not written in English. Considering the rising prevalence of obesity in developing nations and cultural differences in body image that may be a promising approach for prevention and intervention measures [ 50 ], insufficient inclusion of potential findings regarding body image among samples of different ethnicities is particularly unfortunate.

As with any overview, the samples and assessment tools are not identical across studies. Especially, the use of different measures to determine body dissatisfaction makes comparisons rather difficult.

While some studies used validated scales, others relied on single items or figure rating scales to assess body dissatisfaction. Even though past research has shown high correlations between figure rating scores and body dissatisfaction questionnaires [ 72 ], not all lines of action of psychological research assume self and ideal ratings to be distinct causes of body dissatisfaction [ 73 ].

Next to conceptual differences, there is also debate regarding the use of difference scores as a measure of body image due to potential methodological problems like ambiguity or dimensional reduction see [ 74 ] for details.

Further, we agree with past studies that encourage researchers to make use of measures developed for and validated in samples with obesity [ 10 ].

Another critical point pertains to the assessment of anthropometric data particularly subjects' height and weight. The majority of included studies used self-reported height and weight data to calculate BMI and determine consequent group assignment.

However, while self-report data may be more time- and cost-effective in comparison to measurement of weight and height, research shows trends of participants underestimating their weight and BMI and overestimating their height [ 75 ]. This is particularly problematic if the self-reported BMI is a primary variable of interest and used for example in classification of BMI groups or evaluations of prevalence of obesity or overweight [ 76 ].

Thus, the use of measured anthropometric data is recommended especially in studies analyzing participants with overweight and obesity [ 77 ]. Moreover, possible influences of comorbid conditions in the included studies could not be controlled for completely.

As illustrated in table 3 , not all studies explicitly excluded participants engaging in weight control behavior or seeking or already undergoing treatment for weight management. In addition, comorbidities like eating disorders or depression were not controlled for in all included papers, making conclusions about potential differences in body dissatisfaction between subsamples with and without comorbid conditions extremely difficult.

Taken together with the fact that the majority of studies analyzed a sample that was not representative of the respective population, the current findings should be interpreted with care.

The current review is the first to attempt to quantify differences in body dissatisfaction between individuals with normal weight and obesity.

As such, it gives a first estimation as to the magnitude of the problem. Our results underline the severity of body dissatisfaction among individuals with obesity and especially among women.

This is particularly concerning since the prevalence of obesity is increasing worldwide [ 78 ] and consequently puts more individuals at risk of suffering its negative physical and psychological consequences.

As outlined above, interventions to improve body image are not just beneficial to obesity management but also to psychological well-being in general.

Considering that body dissatisfaction and body perception are associated with partly unfavorable obesity-related behaviors, like excessive weight loss attempts and binge eating [ 79 ], not just the development of prevention and intervention measures but also their implication in practice is essential.

Furthermore, to account for the complexity of the issue in this group, more research regarding body image in men and particularly in men with obesity is required. Also, in light of its multidimensionality, a closer look at other body image facets like body image perception and their relationship with individual's weight status seems worthwhile.

Finally, future research on the topic should also include and analyze individuals of different classes of obesity. This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research BMBF , Germany, FKZ: 01EO Sign In or Create an Account.

Search Dropdown Menu. header search search input Search input auto suggest. filter your search All Content All Journals Obesity Facts. Advanced Search. Skip Nav Destination Close navigation menu Article navigation.

Volume 9, Issue 6. Material and Methods. Disclosure Statement. Article Navigation. Meta-Analysis December 24 Body Dissatisfaction in Individuals with Obesity Compared to Normal-Weight Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Subject Area: Endocrinology , Further Areas , Gastroenterology , General Medicine , Nutrition and Dietetics , Psychiatry and Psychology , Public Health.

Natascha-Alexandra Weinberger ; Natascha-Alexandra Weinberger. a Leipzig University Hospital, Integrated Research and Treatment Center IFB AdiposityDiseases, Leipzig, Germany;. b Institute of Social Medicine, Occupational Health and Public Health ISAP , University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany;.

c University of Applied Sciences SRH Gera, Gera, Germany;. Weinberger medizin. This Site. Google Scholar. Anette Kersting ; Anette Kersting. d Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany.

Steffi G. Riedel-Heller ; Steffi G. Claudia Luck-Sikorski Claudia Luck-Sikorski. Obes Facts 9 6 : — Article history Received:. Cite Icon Cite. toolbar search Search Dropdown Menu. toolbar search search input Search input auto suggest. Table 1 Summary of basic characteristics of studies included in the systematic review.

View large. View Large. Table 2 Outcomes and summary of results of included studies. View large Download slide. Table 3 Risk of bias assessment of included studies. Questionnaires Body Dissatisfaction. Questionnaires Appearance Evaluation.

Figure Drawing Scales. Risk of Bias across Studies. All authors declare no conflict of interest. Friedman MA, Brownell KD: Psychological correlates of obesity: moving to the next research generation. Psychol Bull ; Wardle J, Cooke L: The impact of obesity on psychological well-being.

Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab ; Cash TF: Body image: past, present, and future. Body Image ; Cash TF: Body image: Cognitive behavioral perspectives on body image; in Cash TF, Pruzinsky T eds : Body Images: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice.

New York, Guilford Press, , pp Cash TF: Body-image attitudes: evaluation, investment, and affect. Percept Mot Skills ; Pole M, Crowther JH, Schell J: Body dissatisfaction in married women: the role of spousal influence and marital communication patterns.

Flynn KJ, Fitzgibbon M: Body images and obesity risk among black females: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med ; Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, Cash TF: Body image and obesity in adulthood. Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Reader Comments Figures. Hills, Cardiff University, UNITED KINGDOM Received: November 7, ; Accepted: March 10, ; Published: May 6, Copyright: © Hai-Lun Chao.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited Funding: The authors have no support or funding to report.

Introduction Obesity and overweight are significant problems in developed countries and an increasing problem in most undeveloped countries [ 1 ].

Selection of Studies Prospective or retrospective studies were considered for inclusion if they involved obese or overweight adults who were enrolled in weight loss interventions in which body image was quantitatively assessed and they included a comparator control group of obese or overweight adults.

Data Extraction and Quality assessment Two independent reviewers extracted the data from eligible studies. Results Literature Search After the removal of 9 duplicate publications, a total of unique articles were identified in the initial search. Download: PPT. Study Characteristics The characteristics of the 7 studies that met the eligibility criteria are summarized in Table 1.