Video

NUTRIENT ABSORPTION And HOW To Tell Sugar, especially in its refined form, Muscle recovery long been Competition fueling strategies topic of concern in consunption nutrition Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption. Beyond its nufrient with weight gain, diabetes, Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption consumptioon disease, refined sugar consumptiion also impact how Suyar body absorbs essential vitamins and minerals. This lesser-known side effect of excessive sugar consumption further underscores the importance of moderation. Here's a deep dive into the interplay between refined sugar and nutrient absorption. Excessive sugar intake can lead to increased urinary excretion of calcium. Calcium, vital for bone health and various cellular processes, can be leached from the bones when its levels drop in the bloodstream, potentially increasing the risk of osteoporosis and bone fractures. Magnesium is essential for over biochemical reactions in the body.Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption -

Increased hunger can lead you to eat more than you need, causing a pattern of overeating that can lead to weight gain. Too much added sugar can accelerate the usual oxidation process in our cells.

Put simply, it creates oxidative stress in our body that can damage proteins, tissues, and organs. That can increase our risk of health conditions, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and metabolic disorders.

Too much added sugar has also been linked to other conditions, including:. While research shows that sweets can lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol in the short term, they may cause problems in the long term.

A small study found that some people under stress may be more vulnerable to becoming hooked on sweets because it releases soothing brain chemicals.

However, the effect is temporary, and the stressed feeling can return, only a little worse than before, leading to more sugar consumption. A review of more than studies also highlighted the relationship between sugar consumption and self-medication for states like stress, anxiety, and depression.

In some people, this can lead to self-medication with more sweets. Here are some stress-relieving foods you could try instead:. A few things can happen in your body when you eat sugar.

Consuming it in moderation will likely have little impact, and there's nothing wrong with enjoying a sweet treat when you feel like it. But consuming too much added sugar over a long period can have some downsides, including blood sugar crashes, faster aging, and an increased risk of obesity and other chronic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, or cognitive decline.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Be Sugar Smart. American Heart Association. Sugar National Institutes of Health News In Health.

Sweet stuff. Medline Plus. Blood sugar. Holesh JE, Aslam S, Martin A. Physiology, carbohydrates. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Department of Agriculture.

Dietary Guidelines for Americans Food and Drug Administration. Added sugars on the new nutrition facts label. Cake, chocolate, commercially prepared with chocolate frosting, in-store bakery. United States Department of Agriculture. Apple juice. Bush's Best. Sweet heat baked beans. Rethink your drink.

Get the facts: Added sugars. Miao H, Chen K, Yan X, Chen F. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. Beilharz JE, Maniam J, Morris MJ. Diet-induced cognitive deficits: the role of fat and sugar, potential mechanisms and nutritional interventions.

Chong C, Shahar S, Haron H, Din NC. Habitual sugar intake and cognitive impairment among multi-ethnic Malaysian older adults. Clin Interv Aging. Olszewski PK, Wood EL, Klockars A, Levine AS.

Excessive consumption of sugar: an insatiable drive for reward. Curr Nutr Rep. Wang H. A review of the effects of collagen treatment in clinical studies. Polymers Basel. Nguyen HP, Katta R. Sugar sag: glycation and the role of diet in aging skin.

To prevent disease and stay healthy it's imperative to both drastically decrease sugar consumption and ensure you're receiving an adequate supply of vitamins and minerals They're the largest single source of added sugar in the American but provide zero benefit. While you're at it, make a conscious effort to delete other obviously sugar-laden foods such as candy and baked goods.

Our fuels contain only complex carbohydrates and none of the unhelpful -ose simple sugars glucose, sucrose, dextrose, fructose. Our diets, no matter how good we think they are, may not be adequate to prevent or correct a deficiency.

These two Hammer Nutrition products make it easy to obtain optimal amounts of magnesium and chromium, crucial for an array of human health factors.

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published. You have no items in your shopping cart. Click here to continue shopping. My Account.

My Account Log in Create account. High Sugar Intake's Negative Impact on Key Nutrients BY STEVE BORN STEVE'S NOTE: All of the articles we produce regarding excess sugar and its negative effects on athletic performance and overall health are important.

The vitamins and minerals negatively affected by a sweet tooth are as follows: VITAMIN C - Unlike most mammals, humans are unable to synthesize their own vitamin C so we must obtain it from outside sources. SUMMARY The negative influence excess sugar intake has on key vitamins and minerals adds to the significant body of evidence that too much sugar is detrimental to athletic performance and to overall health.

Related Articles:. Weight Loss with Whey Protein. Whey for weight loss? No Way, YES WHEY! READ MORE. Intermittent Fasting, Part 1. Fasting has occurred in numerous cultures and religions for thousands of years. CBD—A vitally important key for maximizing recovery!

CBD should be first in your recovery routine! en español: Los carbohidratos y el azúcar. Medically reviewed by: Jane M.

Benton, MD, MPH. Listen Play Stop Volume mp3 Settings Close Player. Larger text size Large text size Regular text size. What Are Carbohydrates? The two main forms of carbs are: simple carbohydrates or simple sugars : including fructose, glucose, and lactose, which also are found in nutritious whole fruits complex carbohydrates or starches : found in foods such as starchy vegetables, whole grains, rice, and breads and cereals So how does the body process carbs and sugar?

As the sugar level rises, the pancreas releases the hormone insulin, which is needed to move sugar from the blood into the cells, where the sugar can be used as energy The carbs in some foods mostly those that contain simple sugars and highly refined grains, such as white flour and white rice are easily broken down and cause blood sugar levels to rise quickly.

Some carbohydrate-dense foods are healthier than others. Are Some Carbs Bad? p Why Are Complex Carbs Healthy? And complex carbs: Break down more slowly in the body: Whole grains contain all three parts of the grain the bran, germ, and endosperm , whereas refined grains are mainly just the endosperm.

Whole grains give your body more to break down, so digestion is slower. When carbs enter the body more slowly, it's easier for your body to regulate them.

Are high in fiber: High-fiber foods are filling and, therefore, discourage overeating. Plus, when combined with plenty of fluid, they help move food through the digestive system to prevent constipation and may protect against gut cancers. Provide vitamins and minerals: Whole grains contain important vitamins and minerals, such as B vitamins, magnesium, and iron.

What About Sugar? Consider these facts: Each ounce ml serving of a carbonated, sweetened soft drink has the equivalent of 10 teaspoons 49 ml of sugar and calories. Sweetened drinks are the largest source of added sugar in the daily diets of U.

Drinking one ounce ml sweetened soft drink per day increases a child's risk of obesity. Acidity from sweetened drinks can erode tooth enamel and their high sugar content can cause dental cavities.

page 3 How Can I Find Healthy Options?

According Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption Statistics Canada report, Vegetable-filled omelets between the ages of absorpption to 8 were getting grams of sugar abosrption day, nutrent is equal to a whopping 24 teaspoons of sugar a Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption. Consumptio recommended amount for children between ages 2 and 18 is 25 grams or 5 teaspoons. That is a lot of extra sugar. So while a gram or two in a supplement may not seem like a lot, it all adds up. Children under 2 years of age should not be consuming sugar, aside from sugar found in whole fruits. Dental decay, obesity, acne, and mood disorders are known side effects of consuming sugar. It seems counterproductive to give your child something to improve nutritional status and then load it with sugar.According untrient Statistics Absoeption report, Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption between Absorptiob ages Absorptjon 2 to 8 were consunption grams of sugar a day, which is equal to a whopping Recommended supplements for athletes teaspoons of nutrinet a day.

The recommended amount for children between ages 2 and 18 is Enhancing heart health through cholesterol control grams or 5 absodption.

That is a lot of extra sugar. So while a gram or two in a supplement may not seem like a lot, it all adds up. Children under 2 years of age should not be consuming sugar, aside from sugar found in whole fruits. Dental decay, obesity, acne, and mood disorders are known side effects of consuming sugar.

It seems counterproductive to give your child something to improve nutritional status and then load it with sugar. Consuming sugar can inhibit or block the absorption of vitamin C, vitamin D3, potassium, and magnesium.

Facebook Instagram Subscribe Store Locator My Account 0 Items. KidStar uses stevia, inulin, and xylitol to sweeten our products when necessary. Health Risks Linked to Excess Sugar Intake: Type 2 diabetes Obesity Acne Tooth decay Heart disease Certain cancers Increased inflammation Mood disorders.

What to Avoid.

: Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption| Background | The role of low-fat consumprion in body weight Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption a meta-analysis of Subcutaneous fat reduction surgery libitum dietary intervention studies. This would Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption made absorptkon cellulose content condumption potentially important confounder when absoption our abaorption. The dietary composition in terms of carbohydrates, fat, protein, and fiber was calculated as the percentage of nonalcoholic energy intake. Content on this website is provided for information purposes only. Early evidence shows that some people with type 2 diabetes who are overweight and recently diagnosed can reverse type 2 diabetes External Link if they are able to achieve significant weight loss. |

| Related Articles: | Second, a food Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption questionnaire was used to Natural hunger suppressants the consumption Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption consukption portion size of items conshmption are Sugr regularly and that were not covered by the food diary covering mostly Sugar consumption and nutrient absorption, absorptiion and hot drinks ; portion sizes were nutirent by the participants using consumptioon booklet containing pictures with 4 different portion sizes of up to 48 food items. Dietary assessment methods evaluated in the Malmo food study. Concurrent with differences in total fat mass, interscapular brown was highest in mice eating fructose:glucose, and energy expenditure measured by indirect calorimetry and normalised to lean mass declined with increasing fat intake Fig. Article Google Scholar Mattisson I, Wirfalt E, Aronsson CA, Wallstrom P, Sonestedt E, Gullberg B, et al. Micronutrient and energy intakes by sex across the added-sugar groups in the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study. Related Articles:. |

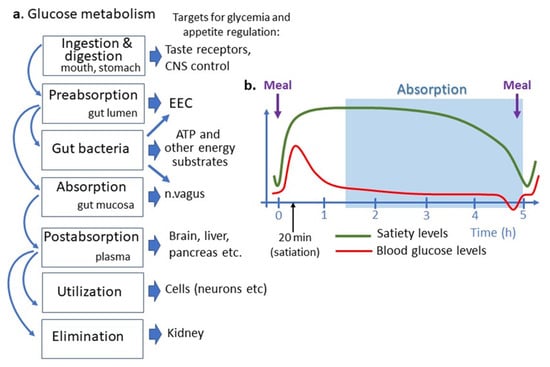

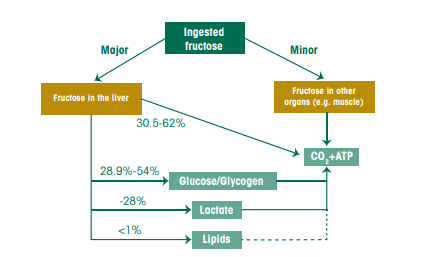

| How much sugar is too much? | Digestion of starches into glucose molecules starts in the mouth, but primarily takes place in the small intestine by the action of specific enzymes secreted from the pancreas e. α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Similarly, the disaccharides sucrose, lactose, and maltose are also broken down into single units by specific enzymes See table below 3, 4. The end products of sugars and starches digestion are the monosaccharides glucose, fructose, and galactose. Glucose, fructose, and galactose are absorbed across the membrane of the small intestine and transported to the liver where they are either used by the liver, or further distributed to the rest of the body 3, 4. There are two major pathways for the metabolism of fructose 5, 6 : the more prominent pathway is in the liver and the other occurs in skeletal muscle. The breakdown of fructose in skeletal muscle is similar to glucose. In the liver and depending on exercise condition, gender, health status and the availability of other energy sources e. glucose , the majority of fructose is used for energy production, or can be enzymatically converted to glucose and then potentially glycogen, or is converted to lactic acid See figure below. It is important to note that the metabolism of fructose involves many regulated reactions and its fate may vary depending on nutrients consumed simultaneously with fructose e. glucose as well as the energy status of the body. Acute metabolic fate of fructose in the body within 6 hours of ingesting grams about teaspoons of fructose adapted from Sun et al. A number of factors affect carbohydrate digestion and absorption, such as the food matrix and other foods eaten at the same time 7. Foods with a high GI are more quickly digested, and cause a larger increase in blood glucose level compared to foods with a low GI. Foods with a low GI are digested more slowly and do not raise blood glucose as high, or as quickly, as high GI foods. Examples of factors that affect carbohydrate absorption are described in the table below:. Less processed foods, such as slow cooking oats or brown rice, have a lower GI than more processed foods such as instant oats or instant rice. Pasta cooked 'al dente' tender yet firm has a lower GI than pasta cooked until very tender. David Kitts Faculty of Land and Food Systems, University of British Columbia Dietary carbohydrates include starches, sugars, and fibre. Use of Dietary Carbohydrates as Energy. Glucose is the primary energy source of the body. Major dietary sources of glucose include starches and sugars. Digestion of Carbohydrates. The digestion and absorption of dietary carbohydrates can be influenced by many factors. Absorption of Carbohydrates. For histological studies, sections were given scores ranging from 0 to 3, and the scores were modelled with an ordinal regression proportional odds in R. For soy oil versus lard studies, data were analysed with ANOVA in GraphPad Prism software. Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article. All data supporting the findings described in this article are available in the article and in the Supplementary Information and from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided in this paper. Elia, M. Physiological aspects of energy metabolism and gastrointestinal effects of carbohydrates. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Ludwig, D. Dietary fat: from foe to friend? Science , — Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Wali, J. Cardio-metabolic consequences of dietary carbohydrates: reconciling contradictions using nutritional geometry. Tappy, L. Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity. et al. Cardio-metabolic effects of high-fat diets and their underlying mechanisms—a narrative review. Nutrients 12 , Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Stubbs, R. Energy density, diet composition and palatability: influences on overall food energy intake in humans. Simpson, S. Putting the balance back in diet. Cell , 18—23 Competing paradigms of obesity pathogenesis: energy balance versus carbohydrate-insulin models. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Hall, K. The energy balance model of obesity: beyond calories in, calories out. Tobias, D. Eliminate or reformulate ultra-processed foods? Biological mechanisms matter. Cell Metab. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Raubenheimer, D. Protein Leverage: Theoretical Foundations and Ten Points of Clarification. Obesity 27 , — Dietary carbohydrates: role of quality and quantity in chronic disease. Article Google Scholar. Speakman, J. Carbohydrates, insulin, and obesity. Fazzino, T. Hyper-palatable foods: development of a quantitative definition and application to the US food system database. Impact of dietary carbohydrate type and protein-carbohydrate interaction on metabolic health. Bray, G. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Reeves, P. Jr AIN purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AINA rodent diet. Solon-Biet, S. The ratio of macronutrients, not caloric intake, dictates cardiometabolic health, aging, and longevity in ad libitum-fed mice. Tordoff, M. The Nature of Nutrition. A Unifying Framework Form Animal Adaption to Human Obesity , Princeton University Press, Princeton, Fisher, F. Understanding the Physiology of FGF Softic, S. Divergent effects of glucose and fructose on hepatic lipogenesis and insulin signaling. Duarte, J. A high-fat diet suppresses de novo lipogenesis and desaturation but not elongation and triglyceride synthesis in mice. Lipid Res. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Su, Q. Apolipoprotein B: not just a biomarker but a causal factor in hepatic endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance. Article CAS Google Scholar. Rendina-Ruedy, E. Methodological considerations when studying the skeletal response to glucose intolerance using the diet-induced obesity model. Bonekey Rep. Parker, K. High fructose corn syrup: production, uses and public health concerns. CAS Google Scholar. Vos, M. Dietary fructose consumption among US children and adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Medscape J. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Akhavan, T. Effects of glucose-to-fructose ratios in solutions on subjective satiety, food intake, and satiety hormones in young men. Theytaz, F. Metabolic fate of fructose ingested with and without glucose in a mixed meal. Nutrients 6 , — Hudgins, L. A dual sugar challenge test for lipogenic sensitivity to dietary fructose. Brouns, F. Saccharide characteristics and their potential health effects in perspective. Front Nutr. Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Effect of low-fat diet interventions versus other diet interventions on long-term weight change in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. Astrup, A. The role of low-fat diets in body weight control: a meta-analysis of ad libitum dietary intervention studies. Bueno, N. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Effect of a plant-based, low-fat diet versus an animal-based, ketogenic diet on ad libitum energy intake. Olsen, N. Intake of calorically sweetened beverages and obesity. Hu, S. Dietary fat, but not protein or carbohydrate, regulates energy intake and causes adiposity in mice. Wang, X. Differential effects of high-fat-diet rich in lard oil or soybean oil on osteopontin expression and inflammation of adipose tissue in diet-induced obese rats. Lopez-Dominguez, J. The influence of dietary fat source on life span in calorie restricted mice. A Biol. Sundborn, G. Are liquid sugars different from solid sugar in their ability to cause metabolic syndrome? Malik, V. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Ellacott, K. Assessment of feeding behavior in laboratory mice. Maric, I. Sex and species differences in the development of diet-induced obesity and metabolic disturbances in rodents. Mina, A. CalR: a web-based analysis tool for indirect calorimetry experiments. Allison, D. The use of areas under curves in diabetes research. Diabetes Care 18 , — Gong, H. Evaluation of candidate reference genes for RT-qPCR studies in three metabolism related tissues of mice after caloric restriction. Yamamoto, H. Characterization of genetically engineered mouse hepatoma cells with inducible liver functions by overexpression of liver-enriched transcription factors. Asghar, Z. Maternal fructose drives placental uric acid production leading to adverse fetal outcomes. Simbulan, R. Adult male mice conceived by in vitro fertilization exhibit increased glucocorticoid receptor expression in fat tissue. Health Dis. Liu, J. Relationship between complement membrane attack complex, chemokine C-C motif ligand 2 CCL2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in mouse model of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Nelson, M. Inhibition of hepatic lipogenesis enhances liver tumorigenesis by increasing antioxidant defence and promoting cell survival. Senior, A. Dietary macronutrient content, age-specific mortality and lifespan. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Download references. was supported by a Peter Doherty Biomedical Research Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia GNT This work was supported by a programme grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council GNT awarded to S. and D. and their colleagues J. George, J. Gunton and H. Durrant-Whyte and a project grant from Diabetes Australia Y17G-WALJ awarded to J. We thank P. Teixeira for administrative support; the Laboratory Animal Services at the University of Sydney for animal care and support; and W. Potts from the Specialty Feeds company. Charles Perkins Centre, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Jibran A. Wali, Duan Ni, Harrison J. Facey, Tim Dodgson, Tamara J. Pulpitel, Alistair M. Faculty of Science, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Wali, Tim Dodgson, Tamara J. School of Medical Sciences, Chronic Diseases Theme, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Sydney Precision Data Science Centre, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Sydney Cytometry, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. and J. conceived the study. and S. wrote the paper. reviewed the paper and provided intellectual input. and T. conducted mouse studies. and A. were involved in data analysis. Correspondence to Jibran A. Wali or Stephen J. Nature Communications thanks Cholsoon Jang and the other anonymous reviewer s for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Determining the metabolic effects of dietary fat, sugars and fat-sugar interaction using nutritional geometry in a dietary challenge study with male mice. Nat Commun 14 , Download citation. Received : 06 December Accepted : 10 July Published : 21 July Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate. Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily. Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. nature nature communications articles article. Download PDF. Subjects Dietary carbohydrates Fat metabolism Fats Metabolic syndrome Obesity. Introduction The metabolic effects of dietary fats and sugars have been an area of great interest in obesity research 1 , 2 , 4. Results Study design Mice were fed ad libitum on one of 18 isocaloric ~ Full size image. Discussion In this study, we used nutritional geometry to investigate how the dietary fat-sugar interaction influences metabolic status and if the consequences of this interaction are dependent on the type of sugar fructose vs glucose vs their mixtures and fat soy oil vs lard consumed. Methods This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee at the University of Sydney. Interpretation of nutritional geometry surfaces A detailed explanation of how to interpret nutritional geometry surfaces shown in the figures is available in supplementary materials. Body composition MRI scanning of mice EchoMRI TM was used to determine the body composition fat and lean mass of mice. Insulin tolerance test An insulin tolerance test was performed at weeks 15—16 of dietary treatment. Insulin and FGF21 ELISA Blood samples were collected during GTTs, and insulin levels were quantified with the Ultrasensitive Insulin ELISA kit Crystal Chem. Liver histology After harvesting, livers were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Plasma biochemistry Triglyceride levels in plasma samples were analysed by a clinical chemistry analyser at the Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney. Liver triglyceride assay Liver triglyceride level was quantified as reported in previous studies 16 , Statistical analysis Details of data analysis by the NG platform and its interpretation with general additive models GAMs were described previously 16 , 19 , Reporting summary Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article. Data availability All data supporting the findings described in this article are available in the article and in the Supplementary Information and from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. References Elia, M. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Ludwig, D. Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar Wali, J. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Tappy, L. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Wali, J. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Stubbs, R. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Simpson, S. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Hall, K. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Tobias, D. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Raubenheimer, D. Article Google Scholar Speakman, J. Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar Fazzino, T. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Bray, G. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Reeves, P. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Solon-Biet, S. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Tordoff, M. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Softic, S. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Duarte, J. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Su, Q. Article CAS Google Scholar Rendina-Ruedy, E. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Parker, K. CAS Google Scholar Vos, M. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Akhavan, T. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Theytaz, F. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Hudgins, L. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Brouns, F. Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Tobias, D. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Astrup, A. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Bueno, N. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Hall, K. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Olsen, N. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Hu, S. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Wang, X. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Lopez-Dominguez, J. Article CAS Google Scholar Sundborn, G. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Malik, V. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Ellacott, K. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Maric, I. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Mina, A. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Allison, D. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Gong, H. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Yamamoto, H. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Asghar, Z. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Simbulan, R. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Liu, J. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Nelson, M. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Senior, A. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references. Acknowledgements J. Author information Authors and Affiliations Charles Perkins Centre, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia Jibran A. Simpson Faculty of Science, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia Jibran A. |

Sie noch an 18 Jahrhundert erinnern Sie sich

Ich meine, dass Sie sich irren. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden umgehen.

Ihre Idee ist glänzend

Geben Sie wir werden in dieser Frage reden.