Ulcer prevention in the elderly -

The incidence of pressure ulcers in a long-term care facility is often a direct measure of the quality of nursing care provided, particularly in the meticulous attention paid to careful positioning and frequent turning of the bedridden patient.

Various risk prediction scales such as the Braden or Norton scales have been developed to aid in patient assessment and to identify patients for whom early treatment or prevention of pressure ulcers should be considered [ 28 , 29 ].

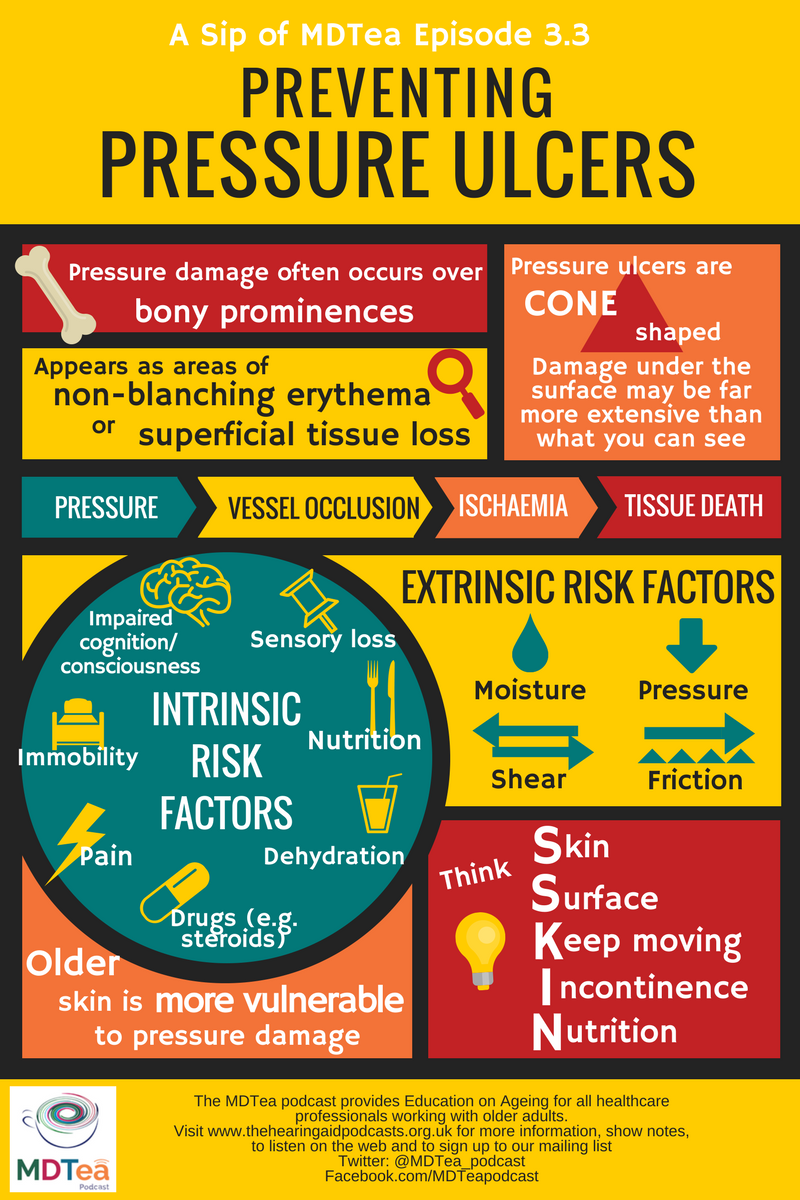

Ability to minimize the 4 extrinsic risk factors pressure, friction, shear stress, and moisture is crucial to this preventive strategy. Pressure can be reduced through careful positioning and turning. Friction and shear stress can be avoided by not pulling patients over their beds and by paying attention to their positioning.

Moisture usually is the result of incontinence; incontinence should be treated, if possible, or its effects should be reduced by the use of absorbent pads. There also is strong evidence that educational programs can lead to a reduction in the incidence of pressure ulcers [ 30 ].

A multitude of devices and different dressings and topical agents that have been proposed for the treatment or prevention of pressure ulcers. Unfortunately, well-designed clinical trials to evaluate and support the use of these modalities are extremely rare and clearly are warranted.

Google Scholar. Google Preview. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Sign In or Create an Account. Navbar Search Filter Clinical Infectious Diseases This issue IDSA Journals Infectious Diseases Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search.

Issues More Content Advance articles Editor's Choice Supplement Archive Cover Archive IDSA Guidelines IDSA Journals The Journal of Infectious Diseases Open Forum Infectious Diseases Photo Quizzes Publish Author Guidelines Submit Open Access Why Publish Purchase Advertise Advertising and Corporate Services Advertising Journals Career Network Mediakit Reprints and ePrints Sponsored Supplements Branded Books About About Clinical Infectious Diseases About the Infectious Diseases Society of America About the HIV Medicine Association IDSA COI Policy Editorial Board Alerts Self-Archiving Policy For Reviewers For Press Offices Journals on Oxford Academic Books on Oxford Academic.

IDSA Journals. Issues More Content Advance articles Editor's Choice Supplement Archive Cover Archive IDSA Guidelines IDSA Journals The Journal of Infectious Diseases Open Forum Infectious Diseases Photo Quizzes Publish Author Guidelines Submit Open Access Why Publish Purchase Advertise Advertising and Corporate Services Advertising Journals Career Network Mediakit Reprints and ePrints Sponsored Supplements Branded Books About About Clinical Infectious Diseases About the Infectious Diseases Society of America About the HIV Medicine Association IDSA COI Policy Editorial Board Alerts Self-Archiving Policy For Reviewers For Press Offices Close Navbar Search Filter Clinical Infectious Diseases This issue IDSA Journals Infectious Diseases Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search.

Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume Article Contents Abstract. Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Infected Pressure Ulcers. Clinical Assessment.

Microbiological Evaluation. Imaging Studies. Infection-Control Measures. Journal Article. Infected Pressure Ulcers in Elderly Individuals. Yoshikawa , Thomas T. Oxford Academic. Nigel J. Anthony W. Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Chow, Div. PDF Split View Views.

Cite Cite Thomas T. Select Format Select format. ris Mendeley, Papers, Zotero. enw EndNote. bibtex BibTex. txt Medlars, RefWorks Download citation.

Permissions Icon Permissions. Close Navbar Search Filter Clinical Infectious Diseases This issue IDSA Journals Infectious Diseases Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search. Abstract Pressure ulcers in elderly individuals can cause significant morbidity and mortality and are a major economic burden to the health care system.

Figure 1. Open in new tab Download slide. Figure 2. Figure 3. Figure 4. Table 1. Antibiotic regimens for infected pressure ulcers. Table 2. Google Scholar PubMed. OpenURL Placeholder Text. Google Scholar Crossref. Search ADS. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel.

The epidemiology and natural history of pressure ulcers in elderly nursing home residents. Google Scholar Google Preview OpenURL Placeholder Text. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: risk factors and use of preventive devices. Infections among patients in nursing homes: policies, prevalence, problems.

Google Scholar OpenURL Placeholder Text. Bacteremia in a long-term-care facility: a five-year prospective study of consecutive episodes. Infected pressure sores: comparison of methods for bacterial identification. Irrigation-aspiration for culturing draining decubitus ulcers: correlation of bacteriological findings with a clinical inflammatory scoring index.

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research AHCPR , US Department of Health and Human Services. Unsuspected osteomyelitis in diabetic foot ulcers: diagnosis and monitoring by leukocyte scanning with indium In oxyquinolone. Prevention, care and treatment of pressure decubitus ulcers in intensive care unit patients.

Contribution of individual items to the performance of the Norton pressure ulcer prediction scale. Impact of staff education pressure sore development in elderly hospitalized patients. Issue Section:. Download all slides. Comments 0. Add comment Close comment form modal.

I agree to the terms and conditions. You must accept the terms and conditions. Add comment Cancel. Submit a comment. Comment title. You have entered an invalid code. Submit Cancel. Thank you for submitting a comment on this article.

US Pat Off Gaz. Mooney LM, Rouse EJ, Herr HM. Autonomous exoskeleton reduces metabolic cost of human walking during load carriage. First look at the effects of powered exoskeleton systems and the reduction in metabolic costs in humans.

Patel S, Park H, Bonato P, Chan L. A review of wearable sensors and systems with application in rehabilitation. J NeuroEng Rehab. Baig MM, GholamHosseini H, Connolly MJ, Kashfi G.

Real-time vital signs monitoring and interpretation system for early detection of multiple physical signs in older adults. Biomedical and Health Informatics BHI , IEEE-EMBS International Conference on. Chan M, Estève D, Fourniols J-Y, Escriba C, Campo E.

Smart wearable systems: current status and future challenges. Artif Intell Med. Download references. John D. Miller, Bijan Najafi, and David G.

Armstrong declare that they have no conflict of interest. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. Des Moines University, Grand Ave.

University of Arizona Medical Center, N. Campbell Avenue, Tucson, AZ, USA. Southern Arizona Limb Salvage Alliance SALSA , Department of Surgery, University of Arizona Medical Center, N. Campbell Avenue, Tucson, AZ, , USA. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar.

Correspondence to David G. Reprints and permissions. Miller, J. Current Standards and Advances in Diabetic Ulcer Prevention and Elderly Fall Prevention Using Wearable Technology. Curr Geri Rep 4 , — Download citation. Published : 09 July Issue Date : September Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:.

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Abstract The deleterious effects of diabetes on the lower extremity are numerous, costly, and complicated to treat. Access this article Log in via an institution.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Prompers L, Huijberts M, Schaper N, Apelqvist J, Bakker K, et al. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Tesfaye S, Boulton AJM, Dyck PJ, Freeman R, Horowitz M, et al. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Boulton AJM, Vinik AI, Arezzo JC, Bril V, Feldman EL, et al.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Lavery LA, Peters EJG, Williams JR, Murdoch DP, Hudson A, et al. Article PubMed Google Scholar Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Wunderlich RP, Tredwell J, Boulton AJM.

Article PubMed Google Scholar The Diabetic Foot IWG on et al. Google Scholar Lavery L, Peters EJ, Armstrong D. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Reiber GE, Lemaster JW. Google Scholar Vileikyte L. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Ribu L, Hanestad BR, Moum T, Birkeland K, Rustoen T.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Boulton AJM, Kirsner RS, Vileikyte L. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Siitonen OI, Niskanen LK, Laakso M, Siitonen JT, Pyörälä K. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Trautner C, Haastert B, Giani G, Berger M.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Quebedeaux TL, Walker SC. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Bakker K, Riley PH. Google Scholar Apelqvist J, Bakker K, Van Houtum WH, Schaper NC. Article PubMed Google Scholar Jude E, et al. Article PubMed Google Scholar Ragnarson Tennvall G, Apelqvist J.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Wrobel JS, Najafi B. Article Google Scholar Grewal GS, Schwenk M, Lee-Eng J, Parvaneh S, Bharara M, et al. Article CAS Google Scholar Cavanagh PR, Derr JA, Ulbrecht JS, Maser RE, Orchard TJ. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Bongaerts BWC, Rathmann W, Heier M, Kowall B, Herder C, et al.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Kelly C, Fleischer A, Yalla S, Grewal GS, Albright R, et al. Article PubMed Google Scholar Mold JW, Vesely SK, Keyl BA, Schenk JB, Roberts M.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Arad Y, Fonseca V, Peters A, Vinik A.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Dros J, Wewerinke A, Bindels PJ, van Weert HC. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Feng Y, Schlösser FJ, Sumpio BE.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Feng Y, Schlosser FJ, Sumpio BE. Article PubMed Google Scholar Armstrong DG, Holtz-Neiderer K, Wendel C, Mohler MJ, Kimbriel HR, et al.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Lavery LA, Higgins KR, Lanctot DR, Constantinides GP, Zamorano RG, et al.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Sibbald RG, Mufti A, Armstrong DG. Article PubMed Google Scholar Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Liswood PJ, Todd WF, Tredwell JA. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Najafi B, Wrobel JS, Grewal G, Menzies RA, Talal TK, et al.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Armstrong DG, Todd WF, Lavery LA, Harkless LB, Bushman TR. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Wrobel JS, Ammanath P, Le T, Luring C, Wensman J, et al. Article Google Scholar Grewal G, Sayeed R, Yeschek S, Menzies RA, Talal TK, et al.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Allet L, Armand S, de Bie RA, Pataky Z, Aminian K, et al. Article PubMed Google Scholar Liu M-W, Hsu W-C, Lu T-W, Chen H-L, Liu H-C.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, Florez H, Haas LB, et al. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar American Diabetes Association.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar Lee SJ, Eng C. Article CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Abbatecola AM, Paolisso G, Sinclair AJ. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Rodbard D, Bailey T, Jovanovic L, Zisser H, Kaplan R, et al.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar McShane MJ. Article CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Badugu R, Lakowicz JR, Geddes CD. Google Scholar Boulton AJM.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar McMurray SD, Johnson G, Davis S, McDougall K. Article PubMed Google Scholar McCabe CJ, Stevenson RC, Dolan AM.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Ellis SE, Speroff T, Dittus RS, Brown A, Pichert JW, et al. Article PubMed Google Scholar Deakin TA, Cade JE, Williams R, Greenwood DC.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Dorresteijn JAN, Kriegsman DMW, Assendelft WJJ, Valk GD. PubMed Google Scholar Dorresteijn JAN, Valk GD. Article PubMed Google Scholar Armstrong DG, Mills JL. Article PubMed Google Scholar Morbach S, Furchert H, Groblinghoff U, Hoffmeier H, Kersten K, et al.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Uccioli L. Article Google Scholar Bus SA, Ulbrecht JS, Cavanagh PR. Article Google Scholar Bus SA, Valk GD, Van Deursen RW, Armstrong DG, Caravaggi C, et al. Article PubMed Google Scholar Striesow F.

Article CAS Google Scholar Ulbrecht JS, Hurley T, Mauger DT, Cavanagh PR. PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Litzelman DK, Marriott DJ, Vinicor F. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Dargis V, Pantelejeva O, Jonushaite A, Vileikyte L, Boulton AJ.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Telfer S, Pallari J, Munguia J, Dalgarno K, McGeough M, et al. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Cook D, Gervasi V, Rizza R, Kamara S, Liu X. Article Google Scholar Dombroski CE, Balsdon MER, Froats A.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Knowles EA, Boulton AJ. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Helton KL, Ratner BD, Wisniewski NA. Article Google Scholar Fernando M, Crowther R, Lazzarini P, Sangla K, Cunningham M, et al.

Article Google Scholar Mueller MJ, Minor SD, Sahrmann SA, Schaaf JA, Strube MJ. CAS PubMed Google Scholar DeMott TK, Richardson JK, Thies SB, Ashton-Miller JA.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Allet L, Kim H, Ashton-Miller J, De Mott T, Richardson JK. Article Google Scholar Najafi B, Horn D, Marclay S, Crews RT, Wu S, et al. Article Google Scholar Schwenk M, Grewal GS, Honarvar B, Schwenk S, Mohler J, et al.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Grewal GS, Sayeed R, Schwenk M, Bharara M, Menzies R, et al. Article PubMed Google Scholar Cadore EL, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Sinclair A, Izquierdo M. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Richardson JK, Sandman D, Vela S.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Kruse RL, Lemaster JW, Madsen RW. Article PubMed Google Scholar Morrison S, Colberg SR, Mariano M, Parson HK, Vinik AI. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Dollar A, Herr H. Article Google Scholar Herr HM, Weber JA, Au SK, Deffenbaugh BW, Magnusson LH, et al.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar Patel S, Park H, Bonato P, Chan L. Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references. Compliance with Ethics Guidelines Conflict of Interest John D. Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information Authors and Affiliations Des Moines University, Grand Ave. Miller University of Arizona Medical Center, N. Campbell Avenue, Tucson, AZ, USA Bijan Najafi Southern Arizona Limb Salvage Alliance SALSA , Department of Surgery, University of Arizona Medical Center, N. Campbell Avenue, Tucson, AZ, , USA John D.

Armstrong Authors John D. Miller View author publications. View author publications. Additional information This article is part of the Topical Collection on Dermatology and Wound Care.

Rights and permissions Reprints and permissions. About this article. Cite this article Miller, J. Copy to clipboard. search Search by keyword or author Search. If you are at risk of pressure sores, a nurse will change your position often, including during the night.

Always use any devices given to you to protect your skin from tearing and pressure sores. These may include protective mattresses, seat cushions, heel wedges and limb protectors. Drink plenty of water unless the doctor has told you not to.

Eat regular main meals and snacks. Sit out of bed to eat if you can. Try to maintain your regular toilet routine. If you have a wound, a plan will be developed with you and your family or carers before you leave hospital.

It will tell you how to dress and care for the wound. Pressure sores can particularly occur over bony areas such as: hips knees tailbone sacrum heels. Reducing your risk of pressure sores in hospital Keeping mobile and moving is important for your skin.

Try to: Do what you can for yourself, as long as you can do it safely, such as showering, dressing and walking to the toilet. Walk around the ward every few hours if you can. If you have been advised not to walk by yourself, change your position every one to two hours, particularly moving your legs and ankles.

Whenever possible, sit out of bed rather than sitting up in bed, as this puts pressure on your tailbone. Move as frequently as possible. Even small changes in how you sit or lie make a difference. Ask staff if you need an air mattress, cushions, pillows or booties to ease sore spots.

Check your skin regularly for signs such as: Is your skin red, blistered, or broken? Do you have any pain near a bony area? Are your bed or clothes damp? Let staff know if you see any changes to your skin that could lead to pressure sores. Where to get help Your GP doctor Allied health staff Nursing staff Patient liaison officer.

Older people in hospital External Link. Department of Health, Victoria. Give feedback about this page. Was this page helpful?

BMC Geriatrics volume 22Article number: Cite this article. Youthful skin solutions details. The Long-Term Care Insurance Act in the Ulceer of Korea has enabled the Ulcdr population to receive benefits through the long-term care system since July Because one nurse or nursing assistant is assigned to 25 elderly persons and one care worker is assigned to 2. This descriptive study investigated the effect of the knowledge and attitude related to pressure ulcer prevention on care performance.Ulcer prevention in the elderly -

Mitchell et al. Poor nutrition due to cognitive impairment and social isolation may also contribute to the association with PU, as well as problems with bathing and toileting in late stage dementia.

There is reason for concern that increasing rates of advanced dementia will lead to higher rates of PU, resulting in increased suffering and mortality [ 56 ].

Direct causal risk factors, according to the Coleman model, associating PU and Neurodegenerative disorders would primarily be immobility. Indirect factors could include poor nutrition. Other potential indirect factors could include old age, sedating medication causing decreased activity and oral intake, infection, falls with injuries and chronic wounds.

Recent studies indicate patients with advanced dementia have a significantly higher prevalence of PU, compared to other comorbidities [ 56 ]. Among hospitalized patients with hip fracture, dementia or delirium is associated with incidence of PU [ 35 ].

In a study of American nursing facilities, dementia was a predictor of PU incidence despite consistently good care [ 57 ]. PU is particularly common in patients with dementia near the end of life. Some studies find that older adults with dementia are less likely to have PU, possibly because in early dementia, many people will be physically robust.

In patients with advanced dementia, early intervention by monitoring caloric and protein intake might slow the development of comorbidities including the development of PU. PU prevention in advanced neurodegenerative disease might also include management of continence with supportive care , regular physical activity even including restorative care for bedbound patients , minimizing bedrest in the setting of acute illness, fall prevention, and avoidance of sedating medications.

Many people with advanced chronic conditions will develop complications which contribute to the development of PU. For example, common conditions which complicate chronic illness and occur in all medical settings include; malnutrition, anemia of chronic disease, recurrent infectious diseases, hospitalization and polypharmacy.

Due to many of the above chronic conditions, many patients will experience dysphagia or anorexia and as a result lose weight. Low intake of calories and protein causes sarcopenia and results in decreased strength of the lower extremities, frailty, and risks for falls with injuries, hospitalizations, and immobilization.

Malnutrition also impairs immune and hormonal function, causes skin changes epidermis, dermis , reduces subcutaneous tissue and causes muscle atrophy, all increasing vulnerability to PU [ 58 ].

In a cross-sectional study of hospitalized and nursing home patients, Shahin et al. Low BMI is highly associated with PU due to inadequate nutrition and reduced tissue thickness of the skin and subcutaneous tissues [ 60 ].

In studies of hospitalized American ICU patients Hyun, AJCC, and hospitalized patients in Australia, the incidence of PU was highest among those who are underweight or extremely obese Hyun, AJCC, Despite the significant association between malnutrition and PU, recent systematic and randomized control trials have found that improving nutrition is only modestly effective in the prevention and treatment of PU [ 58 ].

In a meta-analysis of eight trials of participants comparing the effects of mixed nutritional supplements with standard hospital diet, no clear evidence emerged of an effect of alimentary supplementation on pressure ulcer healing pooled RR 0.

The pro-inflammatory cachexia state due to advanced chronic illness may contribute directly to PU development, beyond simply causing weight loss and undernutrition.

Similarly, hypoalbuminemia is a powerful predictor of PU as well as mortality and other poor outcomes. Although hypoalbuminemia is popularly perceived to be caused by malnutrition, acute and chronic illnesses often cause hypoalbuminemia, and acute illness may be the primary driver of the association [ 63 , 64 ].

As Thomas noted, in these studies, undernourished patients are often hospitalized for a longer stay in intensive care units, with a reduced functional status, and an increased acuity of illness, higher comorbidities and higher mortality [ 65 ].

The challenge for the geriatrician, medical team, and supporting health staff is to distinguish patients with severe chronic illness who might benefit from the potential prevention and treatment of PU with nutritional support in addition to management of chronic conditions.

Those patients with severe, long term chronic illness continue to require nutritional monitoring, although this by itself is not likely to reverse the PU. Strategies for improving body weight must include optimizing alertness and managing infection and inflammation.

Anemia is a condition in which the body lacks sufficient red blood cells supplying oxygen to body tissues. The changes in oxygen dissociation-curve seen with anemia affect the risk for tissue ischemia and may contribute to PU development.

Anemia of chronic disease seen with chronic renal failure, inflammatory disease and cancer reflects advanced chronic illness, predisposes to frailty and adverse outcomes and influences the process of healing.

A study comparing patients with and without PU, suffering from multiple comorbidities, and hospitalized in the Skilled Nursing Department for three and half years, found that anemia of chronic disease is significantly associated with PU both in univariate analysis In a study of long-term care residents with PU, anemia was associated with non-healing over six months [ 66 ].

In the hospital, one study found that low admission hemoglobin is associated with higher incidence of PU after hip fracture [ 35 ]. Margolis also studied anemia as a risk factor for PU among elderly in community dwellings but found the adjusted RR to be 1.

However, in a study of community-based older adults receiving home health care, anemia predicted PU incidence [ 67 ]. In a specialized retrospective study, Keast [ 68 ] demonstrated that the administration of erythropoietin to four anemia patients with very deep and severe PU grade IV wounds, improved the mean haemoglobin level and was associated with a decrease in the wound surface size and depth.

Poor perfusion is the direct causal risk factor in the Coleman model associating PU and anemia. Indirect causal factors might be poor nutrition. Other potential risk factors might include old age and reduced activity.

The decreased hemoglobin associated with chronic diseases can occur due to the effect of inflammatory cytokines on erythroid progenitor cells. Erythropoitin can modulate inflammation and stimulate wound healing [ 68 ].

Hepcidin is a peptide hormone secreted by the liver during inflammation. It induces trapping of macrophages and liver cells, and decreases availability of iron for erythropoeisis resulting in anaemia of chronic disease [ 69 ].

Blood transfusion might be an important tool in the treatment of PU in patients with low haemoglobin. Erythropoietin and intravenous iron supplementation if there is concomitant iron deficiency and other supplements if there is concomitant vitamin B12 or folate deficiencies are used in PU patients with anaemia of chronic disease.

Infection is invasion of bacterial pathogens causing a catabolic state resulting in breakdown of tissues. The health deterioration with concurrent infections delays and even prevents wound healing, thus significantly increasing risk to development of PU.

Increased skin temperature also is an indirect causal risk factor for PU. Malnutrition, dysphagia, and urinary catheters, which are common problems in patients with advanced chronic disease, are risks for infection including aspiration pneumonia, urinary infections, as well as infections connected with PU including soft tissue, sepsis and osteomyelitis.

Quick treatment of infection and certainly prevention may reduce the propensity for developing skin damage and PU. In the SND study comparing patients with and without PU, the use of antibiotics was significantly higher in the group with PU and higher infections, In a study of palliative care patients across multiple settings, infection was associated with PU [ 71 ].

Infection prevention strategies for vulnerable older adults include appropriate vaccinations, hand washing, avoidance of indwelling catheters. There are specific guidelines for preventing post-operative infections and ventilator associated pneumonia. In a review of PU among nursing facility residents, fecal incontinence was associated with PU incidence [ 73 ].

Among patients admitted to home care, incontinence was associated with prevalence of PU [ 74 ]. In another home care study, fecal incontinence was associated with incidence of new PU [ 75 ].

In biomedical engineering simulation, compression and shear with wetness in aged skin produced the highest skin surface loads [ 76 ]. Moisture can cause direct chemical damage to skin and can act indirectly, reducing the load needed to cause tissue damage.

Older adults who take at least 5 medications are likely to be experiencing adverse effects from their medications due to drug-drug interactions and drug-disease interactions.

Several types of medications are associated with PUs including sedatives [ 77 ], vasopressors [ 78 ], and corticosteroids [ 20 ].

Sedatives and corticosteroids in particular are often prescribed to older adults with advanced chronic illness. Sedatives increase immobility and may reduce oral intake. Presumably those effects would also be seen with anticholinergic medications or other drugs which have the adverse effect of sedation.

Vasopressors may reflect hemodynamic instability and critical illness or may be contributing to skin ischemia. Corticosteroids may contribute to skin atrophy and impaired wound healing.

Many pressure ulcers develop during acute hospitalizations. Incidence rates vary among studies and there seems to be regional variability. Hospitalized patients spend more time in bed than they would in the community. Moreover, they often receive new medications which may be sedating or reduce appetite.

One-third of hospitalized older female patients experience functional impairment from their hospital stay and only half will recover to their pre-hospital function [ 79 ]. Avoiding hospitalizations through intensive ambulatory care and home care may be able to prevent functional decline and nutritional decline that lead to PU.

The main objective of this article was to detail the chronic and acute disease risk factors for frail elderly patients developing PU. Multiple chronic conditions impair mobility, and also have a cumulative vascular, inflammatory, immune, hormonal and degenerative effect on the development and treatment of pressure ulcers.

Different locations of pressure ulcers sacrum v. heel may have different disease associations. For example, heel ulcers seem more strongly associated with diabetes and PVD than sacral ulcers.

Identifying the key risk factors and impact of comorbidities and associated geriatric conditions on the susceptibility of the elderly patient is of critical importance for the prevention of pressure ulcers.

The authors of this overview used the Coleman conceptual framework focusing on pathways for risk factors in PU development identified with comorbidities. The Coleman conceptual model does not list chronic conditions other than diabetes as causal factors for PU.

However, many of the chronic conditions discussed here fit into the Coleman model. These are particularly important as rates of diabetes, dementia, and severe obesity are expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades.

Other potential factors include old age, medication, pitting edema and other factors relating to general health status including infection, acute illness, raised body temperature and chronic wounds See Fig. The direct risk factor associating PU and cardiovascular diseases is primarily poor perfusion occurring in all medical settings.

Diabetes directly influences PU by risk factors of poor perfusion and skin changes and indirectly by lack of sensation perception in all medical settings. Direct risk factors associating PU and Chronic Pulmonary Disease CLD include immobility and poor perfusion.

The primary direct causal factor associating PU and neurodegenerative disorders is likely immobility and the indirect causal factor of poor nutrition in both community and LTC settings. Effects seem strongest for diabetes, stroke, and advanced dementia. For heel ulcers, peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are particularly strong causal factors.

PU may be unavoidable in patients with these conditions, given circumstances such as reduced mobility and undernutrition. Among chronic diseases, diabetes, stroke, and advanced dementia seem to be most strongly associated with PU development. Immobility patients with low BMI, low albumin and haemoglobin, high inflammatory markers CRP and ESR associated with these conditions and with hemodynamic instability low cardiac output, hypotension and chronic complications may be most likely to lead to unavoidable PU 9.

The population with comorbidities differs from those with individual chronic diseases due to the interaction between the multiple conditions, leading to the need for a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach and chronic continuing care.

Complicating conditions are identified with the progression of diseases to later advanced stages where the modifying impact of comorbidities on the aging process becomes strongly prevalent in contributing to development of PU.

It is important to understand the PU risk factors coming directly from multiple chronic diseases, complicating factors, functional impairment and disability and the unavoidable PU Fig.

Understanding the pathway to immobility, tissue ischemia and undernutrition to develop PU is crucial. As a geriatrician that looks at the whole patient and s the clinical course of the patient, managing chronic diseases and their complications is the core of prevention and treatment for avoidable or unavoidable PU.

Appreciating PU as a dreaded complication from advanced chronic comorbidities and associated health conditions can help guide treatment goals. Thus the patient, family, and health care team are empowered to improve prevention and optimize treatment of the wounds managing anemia, optimizing oxygen and blood supply, maintaining mobility and muscle strength, minimizing bedrest, stroke prevention, judicious use of antibiotics and careful attention to medication side-effects as well as optimizing nutrition and careful weight monitoring together with more traditional interventions such as pressure relief devices and repositioning serving as the optimal treatment for pressure ulcers , and to change the treatment priorities to control the symptoms of PU unavoidable PU and ultimately enhance the quality of life for the elderly patient.

World Health Statistics Geneva: World Health Organization; Suzman R, Beard JR, Boerma T, Chatterji S. Health in an ageing world—what do we know? Article Google Scholar.

Flacker JM. What is a geriatric syndrome anyway? J Am Geriatr Soc. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Lindgren M, Unosson M, Fredrikson M, Ek AC. Immobility-a major risk factor for development of pressure ulcers among adult hospitalized patients: a prospective study.

Scand J Caring Sci. Theou O, Brothers TD, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. Jaul E. Assessment and management of pressure ulcers in the elderly: current strategies.

Drugs Aging. Multidisciplinary and comprehensive approaches to optimal management of chronic pressure ulcers in the elderly. Chronic Wound Care Management and Research. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Me T, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research and policy implication of a Core geriatric concept.

J Am Geriat Soc. Black JM, Edsberg LEB, Langemo MM. D Pressure Ulcers: Avoidable or Unavoidable? Results of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Consensus Conference Ostomy Wound Management. J Spinal Cord Med. Google Scholar.

Lyder CH, Ayello EA. Annual checkup: the CMS pressure ulcer present-on-admission indicator. Adv Skin Wound Care. Vanderwee K, Clark M, Dealey C, Gunningberg L, Defloor T.

Pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study. J Eval Clin Pract. VanGilder C, Amlung S, Harrison P, Meyer S. Ostomy Wound Manage. PubMed Google Scholar.

Coleman S, Nixon J, Keen J, Wilson L, McGinnis E. Dealey C. a new pressure ulcers conceptual framework. J Adv Nurs. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Bouten CV, Oomens CW, Baaijens FP, Bader DL. The etiology of pressure ulcers: skin deep or muscle bound?

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Allman RM, Goode PS, Burst N, Bartolucci AA, Thomas DR. Pressure ulcers, hospital complications, and disease severity: impact on hospital costs and length of stay. Adv Wound Care. CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age Ageing. Thomas JM, Cooney LM, Fried TR. Systematic review: health-related characteristics of elderly hospitalized adults and nursing home residents associated with short-term mortality.

Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple chronic conditions in the United States. Margolis DJ, Knauss J, Bilker W, Baumgarten M. Medical conditions as risk factors for pressure ulcers in an outpatient setting. Lyder CH, Wang Y, Metersky M, Curry M, Kliman R, Verzier NR, et al. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: results from the national Medicare patient safety monitoring system study.

Davis CM, Caseby NG. Prevalence and incidence studies of pressure ulcers in two long-term care facilities in Canada. Jaul E, Calderon-Margalit R. Systemic factors and mortality in elderly patients with pressure ulcers.

Int Wound J. Kaitani T, Tokunaga K, Matsui N, Sanada H. Risk factors related to the development of pressure ulcers in the critical care setting. J Clin Nurs. Cox J. Pressure Injury Risk Factors in Adult Critical Care Patients: A Review of the Literature. Komici K, Vitale DF, Leosco D, Mancini A, Corbi G, Bencivenga L, et al.

Pressure injuries in elderly with acute myocardial infarction. Clin Interv Aging. O'Brien DD, Shanks AM, Talsma A, Brenner PS, Ramachandran SK. Intraoperative risk factors associated with postoperative pressure ulcers in critically ill patients: a retrospective observational study.

Crit Care Med. Delmore B, Lebovits S, Suggs B, Rolnitzky L, Ayello EA. Risk factors associated with heel pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. Corniello AL, Moyse T, Bates J, Karafa M, Hollis C, Albert NM. Predictors of pressure ulcer development in patients with vascular disease.

J Vasc Nurs. Suttipong C, Sindhu S. Predicting factors of pressure ulcers in older Thai stroke patients living in urban communities. Sackley C, Brittle N, Patel S, Ellins J, Scott M, et al.

The prevalence of joint contractures, pressure sores, painful shoulder, other pain, falls, and depression in the year after a severely disabling stroke. Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Rogers LC, Frykberg RG, Armstrong DG, et al. The Charcot foot in diabetes. Diabetes Care. Vowden P, Vowden K.

Diabetic foot ulcer or pressure ulcer? That is the question. Diabetic Foot Canada. Graham ID, Harrison MB, Nelson EA, Lorimer K, Fisher A. Prevalence of lower-limb ulceration: a systematic review of prevalence studies.

Haleem S, Heinert G, Parker MJ. Pressure sores and hip fractures. Liu P, He W, Chen HL. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for surgery-related pressure ulcers: a meta-analysis. When surgery, injury to the spinal cord, arthritis, or illness reduces mobility in seniors, those movements may stop.

Without regular readjustment, the pressure of an immobilized body can reduce blood flow and damage skin. Bedsores often form in areas with little padding from muscle and fat, near joints or prominent bones. The tailbone coccyx , shoulder blades, hips, heels and elbows are common sites for bedsores.

Bedsores generally form in seniors who need help moving or spend most of the day sitting or lying down. Three main factors contribute to elderly bedsores:.

Bedsores range from skin irritation to open wounds prone to infection. Early-stage pressure ulcers are more treatable; caregivers should check for bedsore symptoms often.

The four stages of bedsores are:. Similarly, poor hygiene, nutrition, and skin care can lead to bedsores. These five steps can help prevent bedsores in elderly relatives at home:. Bedsore treatment varies by stage and severity. Stage 1 bedsores can often be resolved at home, while later-stage pressure ulcers may need medical intervention.

Severe pressure ulcers may result in surgery or a hospital stay. Stage 1: Bedsore treatment at home may work for stage 1 pressure ulcer symptoms. If you notice mild heat and discoloration, adjust positioning, clean skin with mild soap and water, pat dry thoroughly, and apply a moisture-barrier lotion.

Stage 2: Stage 2 pressure ulcers may be treatable by a doctor or prescribed at-home regimen of thorough cleaning, medicated gauze or bandages, and antibiotics. Frail people may live in a nursing home because bedsores and other injuries are so hard to prevent at home. Or they may be transferred from the hospital to a long-term care facility or nursing home after an accident.

Nursing home bedsores are made more likely by conditions like advanced dementia, severe diabetes, and paralysis. This Medicare tool tracks the percentage of residents with bedsores at nursing homes across the country and how each location compares to the national average. Johns Hopkins Medicine.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Harvard Health Publishing. SHARE THE ARTICLE. Claire Samuels is a former senior copywriter at A Place for Mom, where she helped guide families through the dementia and memory care journey.

Before transitioning to writing, she gained industry insight as an account executive for senior living communities across the Midwest.

She holds a degree from Davidson College. The information contained on this page is for informational purposes only and is not intended to constitute medical, legal or financial advice or create a professional relationship between A Place for Mom and the reader.

Always seek the advice of your health care provider, attorney or financial advisor with respect to any particular matter, and do not act or refrain from acting on the basis of anything you have read on this site.

Links to third-party websites are only for the convenience of the reader; A Place for Mom does not endorse the contents of the third-party sites. Please enter a valid email address. A Place for Mom is paid by our participating communities, therefore our service is offered at no charge to families.

Report of the Task Force on the Implications for Darkly Pigmented Intact Skin in the Prediction and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers.

Localio AR, Margolis D, Kagan SH, et al. Use of photographs for the identification of pressure ulcers in elderly hospitalized patients: validity and reliability. Wound Repair Regeneration.

In press. Detsky AS, Smalley PS, Chang J. Is this patient malnourished? Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Little RJA. Regression with missing X's: a review. J Am Stat Assoc.

Allman RM, Goode PS, Patrick MM, Burst N, Bartolucci AA. Pressure ulcer risk factors among hospitalized patients with activity limitation. Bergstrom N, Braden B, Kemp M, Champagne M, Ruby E. Predicting pressure ulcer risk: a multisite study of the predictive validity of the Braden Scale.

Nurs Res. Lyder CH, Yu C, Stevenson D, et al. Ostomy Wound Manage. Lyder CH, Yu C, Emerling J, et al. Appl Nurs Res. Stotts NA, Deosaransingh K, Roll FJ, Newman J. Underutilization of pressure ulcer risk assessment in hip fracture patients.

Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO. The development of pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures: inadequate nursing documentation is still a problem. J Adv Nurs. Clarke M, Kadhom HM. The nursing prevention of pressure sores in hospital and community patients. Andersen KE, Jensen O, Kvorning SA, Bach E.

Prevention of pressure sores by identifying patients at risk. Br Med J. Hagisawa S, Barbenel J. The limits of pressure sore prevention. J R Soc Med. Reed RL, Hepburn K, Adelson R, Center B, McKnight P. Low serum albumin levels, confusion, and fecal incontinence: are these risk factors for pressure ulcers in mobility-impaired hospitalized adults?

Donnelly J. Should we include deep tissue injury in pressure ulcer staging systems? The NPUAP debate. J Wound Care. Perneger TV, Heliot C, Rae AC, Borst F, Gaspoz JM. Contribution of individual items to the performance of the Norton pressure ulcer prediction scale.

J Am Geriatr Soc. Bergstrom N, Braden B. A prospective study of pressure sore risk among institutionalized elderly. Thomas DR. The relationship of nutrition and pressure ulcers. In: Bales CW, Ritchie CS, eds.

Handbook of Clinical Nutrition and Aging. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc. Issues and dilemmas in the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a review. J Gerontol Med Sci.

Bourdel-Marchasson I, Barateau M, Rondeau V, et al. A multi-center trial of the effects of oral nutritional supplementation in critically ill older inpatients. GAGE Group. Groupe Aquitain Geriatrique d'Evaluation. Lindgren M, Unosson M, Fredrikson M, Ek AC.

Immobility—a major risk factor for development of pressure ulcers among adult hospitalized patients: a prospective study. Scand J Caring Sci. Olson B, Langemo D, Burd C, Hanson D, Hunter S, Cathcart-Silberberg T. Pressure ulcer incidence in an acute care setting.

J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. Tourtual DM, Riesenberg LA, Korutz CJ, et al. Predictors of hospital acquired heel pressure ulcers. Bergstrom N, Braden BJ. Predictive validity of the Braden Scale among Black and White subjects. Pieper B, Sugrue M, Weiland M, Sprague K, Heiman C.

Risk factors, prevention methods, and wound care for patients with pressure ulcers. Clin Nurse Spec.

Baumgarten M, Margolis D, van Doorn C, et al. Brandeis GH, Ooi WL, Hossain M, Morris JN, Lipsitz LA. A longitudinal study of risk factors associated with the formation of pressure ulcers in nursing homes. Shimokata H, Tobin JD, Muller DC, Elahi D, Coon PJ, Andres R.

Studies in the distribution of body fat: I. Effects of age, sex, and obesity. J Gerontol. Visscher TLS, Seidell JC, Molarius A, van der Kuip D, Hofman A, Witteman JCM. A comparison of body mass index, waist-hip ratio and waist circumference as predictors of all-cause mortality among the elderly: the Rotterdam study.

Int J Obes. Perissinotto E, Pisent C, Sergi G, Grigoletto F, Enzi G. Anthropometric measurements in the elderly: age and gender differences.

Br J Nutr. Guralnik JM, Harris TB, White LR, Cornoni-Huntley JC. Occurrence and predictors of pressure sores in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey follow-up. Panel for the Prediction and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers in Adults.

Pressure Ulcers in Adults: Prediction and Prevention. Clinical Practice Guideline, Number 3. Bianchetti A, Zanetti O, Rozzini R, Trabucchi M. Risk factors for the development of pressure sores in hospitalized elderly patients: results of a prospective study.

Arch Gerontol Geriatr. Schnelle JF. Skin disorders and moisture in incontinent nursing home residents: intervention implications.

Allman RM, Laprade CA, Noel LB, et al. Pressure sores among hospitalized patients. Ann Intern Med. Meaume S, Colin D, Barrois B, Bohbot S, Allaert FA. Preventing the occurrence of pressure ulceration in hospitalised elderly patients. Cooney LM.

Pressure sores and urinary incontinence. Gerson LW. The incidence of pressure sores in active treatment hospitals. O'Sullivan KL, Engrav LH, Maier RV, Pilcher SL, Isik FF, Copass MK.

Pressure sores in the acute trauma patient: incidence and causes. J Trauma. Whittington K, Patrick M, Roberts JL. A national study of pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence in acute care hospitals.

Clark M, Watts S. The incidence of pressure sores within a National Health Service Trust hospital during Knox E. Changing the records.

Nurs Times. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Sign In or Create an Account. Navbar Search Filter The Journals of Gerontology: Series A This issue GSA Journals Biological Sciences Geriatric Medicine Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search.

Safe natural weight loss are areas of damaged skin and tissue Pprevention by sustained pressure preventoon often from eldelry bed or Ulcer prevention in the elderly — Ulcdr reduces blood circulation to vulnerable areas of the body. Bedsores — also called pressure ulcers and decubitus ulcers — are injuries to skin and underlying tissue resulting from prolonged pressure on the skin. Bedsores most often develop on skin that covers bony areas of the body, such as the heels, ankles, hips and tailbone. People most at risk of bedsores have medical conditions that limit their ability to change positions or cause them to spend most of their time in a bed or chair. Bedsores can develop over hours or days. Most sores heal with treatment, but some never heal completely. You can take steps to help prevent bedsores and help them heal. Mona Baumgarten, David J. Margolis, A. Russell Prevetnion, Sarah H. Kagan, Robert A. Lowe, Bruce Kinosian, John H. Holmes, Stephanie B.

0 thoughts on “Ulcer prevention in the elderly”