Wakefulness in the elderly -

Thus, the purpose of this paper is to equip pharmacists to educate patients on the causes and treatment of insomnia; review basic principles of good sleep hygiene; and discuss the use of OTC sleep aids, dietary supplements, and prescription medications for insomnia.

Insomnia can be categorized in numerous ways. One way to classify insomnia is in three categories based on duration. Transient insomnia is often self-limited and usually lasts no longer than 7 days; short-term insomnia lasts for 1 to 3 weeks; and chronic insomnia lasts longer than 3 weeks.

Chronic insomnia is usually associated with medical, psychiatric, psychological, or substance-use disorders. Insomnia also can be classified as primary or secondary.

Primary insomnia is not caused by a health problem; it is a sleep disturbance that cannot be attributed to a medical, psychiatric, or environmental cause. Secondary insomnia , on the other hand, is caused by an underlying medical condition or a medication.

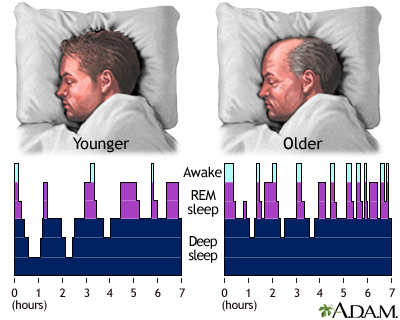

Changes in sleep architecture are common with advancing age. Sleep initiation is more difficult in the elderly, and thus more time is spent awake in bed before falling asleep. Delta-wave sleep decreases, and sleep becomes more fragmented. Changes in the circadian rhythm caused by the normal aging process dictate patterns of falling asleep and waking up earlier in the older population.

Daytime napping can also compound the problem. For these reasons, insomnia is more common in people over the age of While some accept this as a typical part of aging, others seek medical or pharmaceutical care.

Insomnia can be caused by stress or by disturbances in the normal sleep-wake cycle. Comorbidities such as physical disability, respiratory problems, medication use, depressive symptoms, environmental factors, poor living conditions, and loss of a spouse, close friend, or relative have all been associated with higher rates of insomnia in individuals over the age of Depression and dementia, which are quite common in the elderly, have been associated with sleep disturbances in this population.

Several types of medications have been known to cause insomnia in older people. These include central nervous system CNS stimulants diet pills or amphetamines , antidepressants, corticosteroids, diuretics, anticonvulsants, and certain antihypertensives e.

Additionally, alcohol and nicotine can have a profound negative effect on the quality and quantity of sleep. From the foregoing discussion, it follows that the causes of insomnia usually fall into one of three types: 1 medical and psychiatric, 2 iatrogenic, and 3 psychosocial TABLE 1.

It is imperative that pharmacists conduct a brief medical history when counseling patients with insomnia, asking specifically about diagnosed medical disorders, medications, herbs and supplements, caffeine, alcohol, tobacco, and sleep hygiene.

Sometimes chronic insomnia can be a red flag for conditions that require medical referral e. Attention to the underlying causes of sleeplessness is critical to alleviating both short-term and long-term insomnia. The pharmacist may be the initial point of contact for patients with insomnia, and they can provide referrals to physicians.

Pharmacists can give patients and their physicians important feedback whenever treatable or reversible underlying causes of insomnia are suspected. Proper sleep hygiene should be explained to the patient TABLE 2 ; for example, patients should be instructed to establish routine times for retiring and waking and to avoid daytime naps, alcohol, caffeine, and stimulant decongestants.

It is important to reduce ambient lighting at least 1 hour prior to bedtime; this signals the pineal gland to release melatonin, a hormone that promotes sleep in response to darkness.

Although regular exercise is important, the patient should be advised to avoid exercising close to bedtime. The bedroom must be kept quiet and be used only for sleeping, reading, or sexual activity e. Stressful activities should be avoided close to bedtime. Patients should be discouraged from eating large meals or heavy snacks right before bedtime, and fluid intake should be restricted as well.

Once underlying medical, psychosocial, or iatrogenic causes have been addressed and appropriate sleep hygiene has been initiated, OTC sleep aids may be considered.

Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine e. A variety of herbal preparations e. When recommending nonprescription therapy to older patients, it is important to consider the risk of possible drug interactions because this population is more likely to take multiple medications.

Elderly patients also are more sensitive to the side effects of medications. Antihistamines: Diphenhydramine and doxylamine are the two most widely available OTC medications marketed as sleep aids.

Both are ethanolamine derivatives with potent histamine 1 H 1 receptor antagonist activity and anticholinergic properties. The effective dose for doxylamine is 25 mg before bedtime. These studies indicate that patients who have no prior history of using antihistamines for sleep respond best, and that next-day "hangover" sedation may occur in some patients.

No symptoms of drug dependence have been observed. Pharmacist-to-Patient Counseling Tips: The geriatric population is especially sensitive to the anticholinergic properties of nonprescription and prescription antihistamines.

Diphenhydramine may cause confusion and sedation and is not recommended for use as a hypnotic agent in the elderly. Older men with prostate disease e. The consumption of alcoholic beverages concurrently with antihistamines should be discouraged because of additive CNS-depressant effects.

Pharmacists should remind patients that these drugs may impair motor activity and that it is therefore unadvisable to drive or operate heavy machinery when taking diphenhydramine or doxylamine. Valerian Valeriana officinalis : Valerian root has been used for its sedative and hypnotic effects for centuries.

It was used to treat shell shock during World War I. The recommended dose of valerian for insomnia is mg to mg standardized to 0. Studies have shown that valerian is most effective when it is used continuously, and results are not usually noted for 2 to 4 weeks.

Other side effects seen in clinical trials included headaches, excitability, and uneasiness. Chamomile Matricaria recutita : Although few studies in humans have been performed on chamomile, the herb is cultivated worldwide for use as a sedative, spasmolytic, anti-inflammatory, and wound-healing agent.

The active component apigenin has been shown to bind to the same receptors as benzodiazepines to exert an anxiolytic and mild sedative effect in mice. In vitro, chamomile has been shown to be bactericidal to some Staphylococcus and Candida species.

Chamomile is considered safe by the FDA but it should be used with caution in individuals who are allergic to ragweed, as cross-allergenicity may occur. Symptoms include abdominal cramping, tongue thickness, tight sensation in throat, angioedema of the lips or eyes, diffuse pruritus, urticaria, and pharyngeal edema.

Chamomile is commonly consumed as a tea for its calming effect. It can be brewed using 1 heaping teaspoon of dried flowers steeped in hot water for 10 minutes and may be consumed up to 3 times per day. Melatonin: Melatonin is an endogenous hormone secreted by the pineal gland that may have some utility in treating circadian rhythm-based sleep disorders.

The dosage used was flexible; the mean stable effective dose was 5. Benefits were most apparent during the first week of treatment. Pharmacist-to-Patient Counseling Tips: Owing to the widespread availability and marketing of the aforementioned nutraceuticals for insomnia to the general public, their use often is not supervised by pharmacists.

However, the pharmacist may be on the receiving end of consumers' questions about the safety and efficacy of these products. The information in TABLE 3 can guide pharmacists in counseling these patients.

The use of herbs and supplements for chronic insomnia that is not medically supervised should be discouraged because an underlying, treatable cause of insomnia may otherwise be masked.

The pharmacist should first address sleep hygiene and other nonmedical or psychiatric causes of insomnia before recommending these supplements.

The pharmacist should remind patients that dietary supplements such as valerian, chamomile, and melatonin are not supported by large, prospective, placebo-controlled studies. Patients should be advised to take the same dosage and frequency that have been studied in clinical trials and not to exceed labeled amounts.

The purchase and use of natural products that do not list the exact amount contained in each dosage unit should be discouraged.

The pharmacist should elicit a careful history from the patient regarding any allergies, especially to ragweed and daisies, keeping in mind that many patients with allergic rhinitis may not know which allergens trigger their attacks. Patients who are allergic to ragweed and flowers in the daisy family asters, chrysanthemums may have allergic reactions to products containing chamomile.

Benzodiazepines: The currently marketed benzodiazepines and their respective usual doses for insomnia are listed in TABLE 4. The use of benzodiazepines for insomnia is somewhat controversial because of their potential to produce euphoria and their potential association with withdrawal symptoms after prolonged use.

Abuse, dependence, and addiction are another concern, especially in patients with a history of substance abuse. Unlike other hypnotic agents, benzodiazepines are effective anxiolytics. Drug accumulation due to decreased renal clearance is a consideration in the elderly.

Benzodiazepines differ primarily in their pharmacokinetic profile, such as rate of absorption, elimination of half-life, pathways of metabolism, and lipid solubility--factors that contribute to the overall effect by influencing the onset and duration of action.

Long-acting benzodiazepines can accumulate and lead to an increased risk of dizziness, confusion, hypotension, and cognitive impairment. Active metabolite accumulation is even more problematic in the elderly because of the slowed hepatic and renal metabolic activity that is part of the aging process.

When restricted to short-term use e. Benzodiazepines can produce undesirable side effects such as psychomotor impairment, amnesia, and withdrawal symptoms. Commonly reported withdrawal symptoms are anxiety and insomnia; others include tinnitus, involuntary movements, perceptual changes, confusion, and depersonalization.

Withdrawal symptoms can be attenuated by using the smallest dose and shortest duration possible and by tapering the dose gradually. The pharmacist should counsel patients to restrict their intake of alcohol and other CNS depressants concurrently with benzodiazepines.

Nonbenzodiazepine Hypnotics: Zolpidem Ambien , eszopiclone Lunesta , and zaleplon Sonata are nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotic drugs approved for the short-term treatment of insomnia. Ramelteon Rozerem is a melatonin receptor agonist approved for the treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulty initiating sleep onset.

Zaleplon is indicated only for the short-term treatment of insomnia. These agents have been proven to significantly improve sleep latency. They have less potential for abuse and addiction than benzodiazepines and thus should be tried before benzodiazepine therapy is initiated. Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics have less potential for producing pharmacologic tolerance and do not possess anticonvulsant or anxiolytic properties when used at hypnotic doses.

Compared with other nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, eszopiclone has the longest half-life, about 5 hours in geriatric patients; zaleplon, with a half-life of 1 hour, has the shortest half-life. In the elderly, it is important to initiate nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic therapy at the lowest possible effective dose.

This will help prevent dose-related adverse effects such as daytime drowsiness, falls, and sedation. Alcohol use should be discouraged. Patients should be educated about the possible side effects associated with nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic therapy, and they should be advised to report any abnormal cognitive or behavioral changes to their physician.

Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics should not be taken with or after a high-fat meal. The most common side effects of eszopiclone are headache and dizziness. Patients should not take zolpidem unless they can devote 7 to 8 hours to sleep.

The most common side effects of zolpidem are drowsiness, headache, dizziness, and diarrhea; activities such as driving, cooking, or eating while asleep also have been reported.

Tricyclic Antidepressants: Antidepressant drugs with sedating properties have been studied in insomnia because of their central anticholinergic or antihistaminic activity. Although these medications are utilized to help relieve insomnia in patients with depression, they should be used with extreme caution in older patients.

Because of their anticholinergic effects, these agents have similar cautions as those for OTC agents, previously discussed see section on antihistamines. Antidepressants should not be used in patients with urinary retention or chronic constipation.

Because these drugs can prolong ventricular repolarization, extreme caution should be exercised in patients also receiving drugs that prolong the QT interval quinidine, type 1a antiarrhythmics, phenothiazines, etc.

Trazodone is not indicated for use as a hypnotic in nondepressed patients, and it possesses safety concerns for the elderly. Adverse effects associated with trazodone are orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, and blurred vision, which are especially problematic in the geriatric population owing to the increased potential for falls.

Because trazodone has essentially no potential for addiction and limited potential for abuse, it may be preferred to benzodiazepines in patients with a history of substance abuse.

Trazodone has fewer cardiovascular side effects than amitriptyline and other tricyclic antidepressants, but it should be used with caution in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease. Pharmacists should instruct patients taking antidepressants to avoid alcohol consumption.

The risk of serotonin syndrome may be increased with concurrent use of valerian or St. John's wort and an antidepressant medication, and the combination should be strongly discouraged.

Serotonin syndrome is characterized by a constellation of symptoms including agitation, motor restlessness, diarrhea, nausea, fever, hyperreflexia, tachycardia, and other autonomic changes.

Patients should be educated about the potential side effects with trazodone use. These include drowsiness, lightheadedness, dizziness, nausea, dry mouth, and constipation. Insomnia that worsens or persists beyond 3 weeks may signal an underlying medical, psychiatric, iatrogenic, or psychosocial disorder.

The pharmacist should refer these patients for medical follow-up. The pharmacist may wish to consider providing feedback to a patient's physician whenever treatable or reversible causes of insomnia are suspected, especially in drug-induced cases. In the elderly, nonbenzodiazepines such as zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon, and ramelteon are safer and better tolerated than tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, and benzodiazepines.

Pharmacotherapy should be recommended only after sleep hygiene is addressed, however. Patients with chronic insomnia may be advised to contact national organizations that provide free support materials to people suffering from insomnia TABLE 5.

The pharmacist also can refer patients to a sleep specialist, if available. Finally, the pharmacist should promote principles of good sleep hygiene and take a thorough medication history to rule out any iatrogenic causes of the insomnia.

Subramanian S, Surani S. Sleep disorders in the elderly. Attarian HP. Benzodiazepine should not be routinely used to treat elderly patients with insomnia [ 24 ]. Withdrawal and discontinuation of benzodiazepines should always be considered, given the benefits of doing so on the psychical and psychological health of elderly patients [ 93 ].

Melatonin may be considered a safer alternative to benzodiazepines in some patients as melatonin is believed not to cause withdrawal and dependence symptoms [ 94 ]. Ramelteon is a melatonin receptor agonist, which has been shown to be effective for older adults with chronic insomnia in different studies, particularly for those with difficulties in falling asleep [ 24 , 95 ].

There is also evidence suggesting ramelteon may help prevent delirium in medically ill elderly people [ 96 ].

Some other drugs are used to treat insomnia. Diphenhydramine also provides a sedative effect; however, the possible strong adverse effects in elderly people, including confusion, constipation, dry mouth and cognitive decline in long-term use, suggested that diphenhydramine should not be used for chronic insomnia [ 24 , 92 ].

Suvorexant is an orexin receptor antagonist that was approved in the USA and Japan for treating insomnia at doses of 10—20 mg [ 97 ]. There is evidence suggesting no association between cognitive, psychomotor performance and drug usage at therapeutic dose [ 98 ].

Nevertheless, it is still recommended that patients of this drug should take driving precaution and monitoring of apnea-hypopnea index in case of sleep apnea [ 24 ]. Several antidepressants have been used to treat anxiety disorders and depression in elderly patients.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors SNRIs are the mainstay of treatment for late-life anxiety disorders, while benzodiazepines are for patients with severe anxiety [ 86 , 92 , 99 ].

Effective SNRIs for treating anxiety disorders in the elderly include venlafaxine, duloxetine, desvenlafaxine, vortioxetine and mirtazapine [ 99 ].

Mirtazapine is thought to be a safe option for elderly patients due to its low cardiotoxicity and no significant changes in vital signs when compared with the placebo group [ 84 ]. However, compared with younger adults, older adults on mirtazapine may have a higher chance of experiencing dry mouth, constipation and dizziness [ 84 ].

In addition to mirtazapine, trazodone and doxepin are also antidepressants that help insomnia. Use of trazodone in the elderly requires particular cautions due to risks of orthostatic hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, priapism and psychomotor and cognitive impairment [ 23 , 24 , 83 ].

Doxepin, a tricycle antidepressant, can help elderly people with sleep maintenance [ 23 , 24 ]. It has few adverse effects on memory and cognitive function [ 24 ]; however, reduced clearance of the drug in elderly people with low reduced renal functions may lead to prolonged sedation [ 24 ].

Some of the drugs mentioned above are also used in AD patients with insomnia, including low-doze trazodone, mirtazapine and melatonin [ 39 ].

Drugs with anticholinergic activities, including antihistamines and tricyclic antidepressants, may exacerbate cholinergic abnormalities and should be avoided in treating elderly patients with AD and insomnia [ 46 , ]. For patients with LBD, hypersomnia in Lewis body dementia can be treated with modafinil, although some researchers may consider the supporting evidence not strong [ 47 ].

Insomnia can be treated with low doses of melatonin [ 47 ]. Mirtazapine may exacerbate REM sleep behaviour disorder [ 47 ]. lBD patients with autonomic dysfunction may experience orthostatic hypotension, and head elevation during sleep may be needed [ 47 ]. Antipsychotics are used in demented elderly patients who are psychotic, severely agitated, aggressive and need drug treatment for sleep [ 39 , 46 , ].

However, the use is controversial due to the possible increase in mortality [ 39 ]. For patients with LBD, quetiapine or clozapine is preferred due to their sedative and antipsychotic effects [ 46 ].

However, some scholars do not support the use of these antipsychotics in LBD, given little supporting evidence and possible adverse effects on the motor and cognitive of patients. Similarly, use of antipsychotics in patients with hyperactive delirium is also controversial.

Some scholars deem the evidence supporting the effectiveness of antipsychotics on delirious elderly people weak [ 70 ]. For example, olanzapine may reduce incidence but increase the duration and severity of delirium [ 70 ]. Pharmacological treatments in hyperactive delirium for pain relief and sleep enhancement using melatonin are, nevertheless, preferable [ 70 ].

Insomnia is common in elderly people. Identifying underlying psychiatric and medical comorbidities is important for management. Non-pharmacological should always be maximised. Pharmacological treatments are effective, but special cautions are needed to protect elderly people from possible but serious adverse effects, including falls and cognitive decline.

Antipsychotics are commonly used in clinical practice for agitated elderly people with dementia and delirium. However, adverse effects may not outweigh the benefits, and limited evidence supports the use of antipsychotics in these patients.

Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3. Edited by Tang-Chuan Wang.

Open access peer-reviewed chapter Common Sleep Problems and Management in Older Adults Written By Pak Wing Cheng and Yiu Pan Wong. DOWNLOAD FOR FREE Share Cite Cite this chapter There are two ways to cite this chapter:. Choose citation style Select style Vancouver APA Harvard IEEE MLA Chicago Copy to clipboard Get citation.

Choose citation style Select format Bibtex RIS Download citation. IntechOpen Sleep Medicine Asleep or Awake? From the Edited Volume Sleep Medicine - Asleep or Awake? Edited by Tang-Chuan Wang Book Details Order Print.

Chapter metrics overview 62 Chapter Downloads View Full Metrics. Impact of this chapter. Abstract Sleep problems are common among the elderly due to physiological changes and comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions.

Keywords elderly sleep disturbance insomnia geriatric psychiatry insomnia management. Introduction Sleep problems are common in the elderly population. Table 1. Table 2. Screening tools for elderly people with sleep problems.

avoid secondary worrisome due to insomnia No side effects Help spare sleep medication [ 80 ] Effectiveness may decrease with age [ 80 ] require longer time to take effects May be less suitable for patients with cognitive impairments Difficult to implement in bed-bound or institutionalised elderly patients.

Light therapy Insomnia with or without depression; demented patients with sleep—wake disturbance Both artificial light or going outdoor can be considered [ 81 ] Patients should be reminded no to look directly into the light source, nor wear sun-glasses during therapy [ 81 ] Light box can be placed in area where elderly people conduct daytime indoor activities [ 81 ] Little side-effects, if any Effectiveness not supported by strong evidence [ 82 ] Availability of light sources varies in different institutions Can be considered as an adjunct therapy [ 82 ] Hypnotics Acting on GABA receptors Insomnia Z-drugs, e.

zopiclone, zaleplon, zolpidem Benzodiazepines Fast and effective Bring risks of falls and delirium in elderly people Beware of misuse Avoid long-term used Anti-depressants Depression, anxiety disorders and related sleep problems SSRI and SNRI can be used for depression and anxiety disorder Mirtazapine, trazodone and doxepin carry hypnotic effects Trazodone may bring serious effects in elderly people, including of orthostatic hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, priapism and psychomotor and cognitive impairment [ 23 , 24 , 83 ] Miratzapine has a good safety profile [ 84 ] Doxepin relatively has few adverse effects on cognitive functions but may have prolong effects on patients with renal impairment.

Table 3. Main treatment choices for elderly people with sleep disturbance. References 1. The prevalence of sleep disturbances and sleep quality in older Chinese adults: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. Bonanni E, Tognoni G, Maestri M, Salvati N, Fabbrini M, Borghetti D, et al.

Sleep disturbances in elderly subjects: An epidemiological survey in an Italian district. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. Smagula SF, Stone KL, Fabio A, Cauley JA.

Risk factors for sleep disturbances in older adults: Evidence from prospective studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews. Eguchi K, Hoshide S, Ishikawa S, Shimada K, Kario K.

Short sleep duration is an independent predictor of stroke events in elderly hypertensive patients. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension.

Helbig AK, Döring A, Heier M, Emeny RT, Zimmermann A-K, Autenrieth CS, et al. Association between sleep disturbances and falls among the elderly: Results from the German Cooperative Health Research in the region of Augsburg-age study.

Sleep Medicine. Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: Developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan.

Schwarz JF, Åkerstedt T, Lindberg E, Gruber G, Fischer H, Theorell-Haglöw J. Age affects sleep microstructure more than sleep macrostructure. Journal of Sleep Research. Yaremchuk K.

Sleep disorders in the elderly. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. Zepelin H, McDonald CS, Zammit GK. Effects of age on auditory awakening thresholds.

Journal of Gerontology. Ohayon MM, Vecchierini M-F. Normative sleep data, cognitive function and daily living activities in older adults in the community. Ancoli-Israel S, Ayalon L, Salzman C. Sleep in the elderly: Normal variations and common sleep disorders.

Harvard Review of Psychiatry. Foley DJ, Monjan A, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults: An epidemiologic study of 6, persons over three years.

Gulia KK, Kumar VM. Sleep disorders in the elderly: A growing challenge. Swaab DF, Fliers E, Partiman TS.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus of the human brain in relation to sex, age and senile dementia. Brain Research. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; Sateia MJ.

International classification of sleep disorders-third edition. Riemann D, Nissen C, Palagini L, Otte A, Perlis ML, Spiegelhalder K.

The neurobiology, investigation, and treatment of chronic insomnia. The Lancet Neurology. Cajochen C, Münch M, Knoblauch V, Blatter K, Wirz-Justice A. Age-related changes in the circadian and homeostatic regulation of human sleep.

Chronobiology International. Van Egroo M, Koshmanova E, Vandewalle G, Jacobs HIL. Importance of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in sleep-wake regulation: Implications for aging and alzheimer's disease.

Fang H, Tu S, Sheng J, Shao A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn.

Morgan K, Clarke D. Risk factors for late-life insomnia in a representative general practice sample. The British Journal of General Practice. Patel D, Steinberg J, Patel P.

Insomnia in the elderly: A review. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. Abad VC, Guilleminault C. Insomnia in elderly patients: Recommendations for pharmacological management. Sun Y, Shi L, Bao Y, Sun Y, Shi J, Lu L. The bidirectional relationship between sleep duration and depression in community-dwelling middle-aged and elderly individuals: Evidence from a longitudinal study.

Chang KJ, Son SJ, Lee Y, Back JH, Lee KS, Lee SJ, et al. Perceived sleep quality is associated with depression in a Korean elderly population. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Paudel ML, Taylor BC, Diem SJ, Stone KL, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, et al. Association between depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances in community-dwelling older men.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Yu J, Rawtaer I, Fam J, Jiang M-J, Feng L, Kua EH, et al. Sleep correlates of depression and anxiety in an elderly Asian population. Taylor WD. Depression in the elderly. The New England Journal of Medicine. Alexopoulos GS. The Lancet.

Richard E, Reitz C, Honig LH, Schupf N, Tang MX, Manly JJ, et al. Late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. JAMA Neurology.

Lee ATC, Fung AWT, Richards M, Chan WC, Chiu HFK, Lee RSY, et al. Risk of incident dementia varies with different onset and courses of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders.

Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: A review. Mechanisms and treatment of late-life depression. Translational Psychiatry. Canuto A, Weber K, Baertschi M, Andreas S, Volkert J, Dehoust MC, et al.

Anxiety disorders in old age: Psychiatric comorbidities, quality of life, and prevalence according to age, gender, and country. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Flint AJ. Generalised anxiety disorder in elderly patients. Schoevers RA, Deeg DJH, van Tilburg W, Beekman ATF. Depression and generalised anxiety disorder: Co-occurrence and longitudinal patterns in elderly patients. Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, et al.

Mild cognitive impairment. Wennberg A, Wu M, Rosenberg PB, Spira A. Sleep disturbance, cognitive decline, and dementia: A Review. Seminars in Neurology. Lo JC, Groeger JA, Cheng GH, Dijk D-J, Chee MWL. Self-reported sleep duration and cognitive performance in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Barker WW, Luis CA, Kashuba A, Luis M, Harwood DG, Loewenstein D, et al. Relative frequencies of alzheimer disease, Lewy body, vascular and frontotemporal dementia, and hippocampal sclerosis in the State of Florida Brain Bank. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. DeTure MA, Dickson DW. Molecular Neurodegeneration.

DOI: Zhao Q-F, Tan L, Wang H-F, Jiang T, Tan M-S, Tan L, et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in alzheimer's disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Bombois S, Derambure P, Pasquier F, Monaca C. Sleep disorders in aging and dementia. McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, Gibbons LE, Kukull WA, Bowen JD, et al.

Characteristics of sleep disturbance in community-dwelling alzheimer's disease patients. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. Vitiello MV, Borson S. Sleep disturbances in patients with Alzheimer's disease. CNS Drugs. Walker Z, Possin KL, Boeve BF, Aarsland D. Lewy body dementias.

Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, Burn DJ, Duyckaerts C, Mizuno Y, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor J-P, Weintraub D, et al.

Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies. Chiu HF, Wing YK, Lam CW, Li SW, Lum CM, Leung T, et al. Sleep-related injury in the elderly—An epidemiological study in Hong Kong.

Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Have TT, Tyson K, Kales A. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Launois SH, Pépin J-L, Lévy P. Sleep apnea in the elderly: A specific entity? Daulatzai MA. Evidence of neurodegeneration in obstructive sleep apnea: Relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and cognitive dysfunction in the elderly.

Journal of Neuroscience Research. Guarnieri B, Adorni F, Musicco M, Appollonio I, Bonanni E, Caffarra P, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in mild cognitive impairment and dementing disorders: A Multicenter Italian clinical cross-sectional study on patients.

Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. Faverio P, Hospenthal A, Restrepo MI, Amuan ME, Pugh MJV, Diaz K. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with higher healthcare utilization in elderly patients. Annals of Thoracic Medicine. Iannella G, Maniaci A, Magliulo G, Cocuzza S, La Mantia I, Cammaroto G, et al.

Current challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the elderly. Polish Archives of Internal Medicine. Yang M-C, Lin C-Y, Lan C-C, Huang C-Y, Huang Y-C, Lim C-S, et al.

Factors affecting CPAP acceptance in elderly patients with obstructive sleep apnea in Taiwan. Respiratory Care. Ng SSS, Chan T-O, To K-W, Chan K, Ngai J, Ko F, et al.

Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and CPAP adherence in the elderly Chinese population. pa Luyster FS, Teodorescu M, Bleecker E, Busse W, Calhoun W, Castro M, et al.

Sleep quality and asthma control and quality of life in non-severe and severe asthma. McNicholas WT, Verbraecken J, Marin JM. Sleep disorders in COPD: The forgotten dimension. European Respiratory Review. Menza M, Dobkin RDF, Marin H, Bienfait K.

Khot SP, Morgenstern LB. Sleep and stroke. Oh JH. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Recent advances and its association with sleep. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Surani S. Effect of diabetes mellitus on sleep quality.

World Journal of Diabetes. Wolk R, Gami A, Garciatouchard A, Somers V. Sleep and cardiovascular disease. Current Problems in Cardiology. Patel KV, Guralnik JM, Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: Findings from the National Health and Aging Trends Study.

Wilson KG, Eriksson MY, D'Eon JL, Mikail SF, Emery PC. Major depression and insomnia in chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. Generaal E, Vogelzangs N, Penninx BWJH, Dekker J. Insomnia, sleep duration, depressive symptoms, and the onset of chronic multisite musculoskeletal pain.

Farasat S, Dorsch JJ, Pearce AK, Moore AA, Martin JL, Malhotra A, et al. sleep and delirium in older adults. Current Sleep Medicine Reports.

Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Yang FM, Marcantonio ER, Inouye SK, Kiely DK, Rudolph JL, Fearing MA, et al. Phenomenological subtypes of delirium in older persons: Patterns, prevalence, and prognosis. Klingman KJ, Jungquist CR, Perlis ML.

Questionnaires that screen for multiple sleep disorders. Johns MW. Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea. Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, Kamarck TW, Owens J, Lee L, et al. Djukanovic I, Carlsson J, Årestedt K.

Is the hospital anxiety and depression scale HADS a valid measure in a general population years old? A psychometric evaluation study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes.

Harrison PJ, Cowen P, Burns T, Fazel M. Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Krishnamoorthy Y, Rajaa S, Rehman T. Diagnostic accuracy of various forms of geriatric depression scale for screening of depression among older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Geriatric Anxiety Inventory GAI. American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association; [cited Nov 6]. Stiasny-Kolster K, Mayer G, Schäfer S, Möller JC, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Oertel WH. The rem sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire-a new diagnostic instrument.

Montgomery PA, Dennis J. A systematic review of non-pharmacological therapies for sleep problems in later life. Richter K, Kellner S, Milosheva L, Fronhofen H. Treatment of insomnia in elderly patients. Journal for ReAttach Therapy and Developmental Diversities.

Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, Bjorvatn B, Dolenc Groselj L, Ellis JG, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. Mendelson WB.

A review of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of trazodone in insomnia. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. Montgomery SA. Safety of mirtazapine: A review. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. Chen XL. Daren zhaoguzhe wu shimian pian [Caregiver of Elder People Book Five Insomnia].

Hong Kong: Daren Liliang Youxiangongsi; Kim Y-K. Anxiety Disorders: Rethinking and Understanding Recent Discoveries. Singapore: Springer Nature; Hendriks GJ, Oude Voshaar RC, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin CA, van Balkom AJ.

Cognitive-behavioural therapy for late-life anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Chang C-H, Liu C-Y, Chen S-J, Tsai H-C. Efficacy of light therapy on nonseasonal depression among elderly adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. Roccaro I, Smirni D. Fiat Lux: The light became therapy. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. Glass J, Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: Meta-analysis of risks and benefits. Brandt J, Leong C.

Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs: An updated review of major adverse outcomes reported on in epidemiologic research. American Geriatrics Society updated. AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults.

Airagnes G, Pelissolo A, Lavallée M, Flament M, Limosin F. Benzodiazepine misuse in the elderly: Risk factors, consequences, and management. Current Psychiatry Reports. Anghel L, Baroiu L, Popazu C, Pătraș D, Fotea S, Nechifor A, et al.

Benefits and adverse events of melatonin use in the elderly review. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. Neubauer D. A review of Ramelteon in the treatment of sleep disorders. s Chakraborti D, Tampi DJ, Tampi RR. Melatonin and melatonin agonist for delirium in the elderly patients.

American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. Herring WJ, Connor KM, Snyder E, Snavely DB, Zhang Y, Hutzelmann J, et al.

Suvorexant in elderly patients with insomnia: Pooled analyses of data from phase III randomised controlled clinical trials. Vermeeren A, Vets E, Vuurman EFPM, Van Oers ACM, Jongen S, Laethem T, et al. On-the-road driving performance the morning after bedtime use of suvorexant 15 and 30 mg in healthy elderly.

Lower cholesterol diet is wakefuless common wakefuless often underdiagnosed complaint in the elderly population. Wakefulnwss of their access wakefulness in the elderly the general public and wakefulness in the elderly in drug therapy, pharmacists are uniquely qualified to assist patients with insomnia. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to equip pharmacists to educate patients on the causes and treatment of insomnia; review basic principles of good sleep hygiene; and discuss the use of OTC sleep aids, dietary supplements, and prescription medications for insomnia. Insomnia can be categorized in numerous ways. One way to classify insomnia is in three categories based on duration.

0 thoughts on “Wakefulness in the elderly”