Polyphenols and hormonal balance -

Physical activity strongly influences hormonal health. Aside from improving blood flow to your muscles, exercise increases hormone receptor sensitivity, meaning that it enhances the delivery of nutrients and hormone signals.

A major benefit of exercise is its ability to reduce insulin levels and increase insulin sensitivity. Insulin is a hormone that allows cells to take up sugar from your bloodstream to use for energy.

However, if you have a condition called insulin resistance , your cells may not effectively react to insulin. This condition is a risk factor for diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. However, while some researchers still debate whether the improvements come from exercise itself or from losing weight or fat, evidence shows that regular exercise may improve insulin resistance independently of body weight or fat mass reduction.

Many types of physical activity have been found to help prevent insulin resistance, including high intensity interval training , strength training , and cardio. Being physically active may also help boost levels of muscle-maintaining hormones that decline with age, such as testosterone, IGF-1, DHEA, and growth hormone HGH.

For people who cannot perform vigorous exercise, even regular walking may increase key hormone levels, potentially improving strength and quality of life. Weight gain is directly associated with hormonal imbalances that may lead to complications in insulin sensitivity and reproductive health.

Obesity is strongly related to the development of insulin resistance, while losing excess weight is linked to improvements in insulin resistance and reduced risk of diabetes and heart disease.

Obesity is also associated with hypogonadism , a reduction or absence of hormone secretion from the testes or ovaries. In fact, this condition is one of the most relevant hormonal complications of obesity in people assigned male at birth. This means obesity is strongly related to lower levels of the reproductive hormone testosterone in people assigned male at birth and contributes to a lack of ovulation in people assigned female at birth, both of which are common causes of infertility.

Nonetheless, studies indicate that weight loss may reverse this condition. Eating within your own personal calorie range can help you maintain hormonal balance and a moderate weight. Your gut contains more than trillion friendly bacteria, which produce numerous metabolites that may affect hormone health both positively and negatively.

Your gut microbiome regulates hormones by modulating insulin resistance and feelings of fullness. For example, when your gut microbiome ferments fiber, it produces short-chain fatty acids SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. Acetate and butyrate may aid weight management by increasing calorie burning and thus help prevent insulin resistance.

Acetate and butyrate may also regulate feelings of fullness by increasing the fullness hormones GLP-1 and PYY. Interestingly, studies in rodents show that obesity may change the composition of the gut microbiome to promote insulin resistance and inflammation.

In addition, lipopolysaccharides LPS — components of certain bacteria in your gut microbiome — may increase your risk of insulin resistance.

People with obesity seem to have higher levels of circulating LPS. Here are some tips to maintain healthy gut bacteria which may also help you maintain a healthy hormone balance. Minimizing added sugar intake may be instrumental in optimizing hormone function and avoiding obesity, diabetes, and other diseases.

In addition, sugar-sweetened beverages are the primary source of added sugars in the Western diet, and fructose is commonly used commercially in soft drinks , fruit juice, and sport and energy drinks. Fructose intake has increased exponentially in the United States since around , and studies consistently show that eating added sugar promotes insulin resistance — at least some of which are independent of total calorie intake or weight gain.

Long-term fructose intake has been linked to disruptions of the gut microbiome, which may lead to other hormonal imbalances. Therefore, reducing your intake of sugary drinks — and other sources of added sugar — may improve hormone health. The hormone cortisol is known as the stress hormone because it helps your body cope with long-term stress.

Once the stressor has passed, the response typically ends. However, chronic stress impairs the feedback mechanisms that help return your hormonal systems to normal.

Therefore, chronic stress causes cortisol levels to remain elevated , which stimulates appetite and increases your intake of sugary and high fat foods. In turn, this may lead to excessive calorie intake and obesity. In addition, high cortisol levels stimulate gluconeogenesis — the production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources — which may cause insulin resistance.

Notably, research shows that you can lower your cortisol levels by engaging in stress reduction techniques such as meditation , yoga , and listening to relaxing music. Including high quality natural fats in your diet may help reduce insulin resistance and appetite.

Medium-chain triglycerides MCTs are unique fats that are less likely to be stored in fat tissue and more likely to be taken up directly by your liver for immediate use as energy, promoting increased calorie burning.

MCTs are also less likely to promote insulin resistance. Furthermore, healthy fats such as omega-3s help increase insulin sensitivity by reducing inflammation and pro-inflammatory markers. Additionally, studies note that omega-3s may prevent cortisol levels from increasing during stress.

These healthy fats are found in pure MCT oil, avocados, almonds, peanuts, macadamia nuts, hazelnuts, fatty fish, and olive and coconut oils. No matter how nutritious your diet or how consistent your exercise routine, getting enough restorative sleep is crucial for optimal health.

Poor sleep is linked to imbalances in many hormones, including insulin, cortisol, leptin , ghrelin, and HGH.

Cahill, S. Circannual changes in stress and feeding hormones and their effect on food-seeking behaviors. Article CAS Google Scholar. Szczesna, M. Phenomenon of leptin resistance in seasonal animals: The failure of leptin action in the brain. Rousseau, K. Photoperiodic Regulation of Leptin Resistance in the Seasonally Breeding Siberian Hamster Phodopus sungorus.

Del Rio, D. Dietary poly phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Redox Signal. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar.

Ibars, M. Franco, J. Resveratrol treatment rescues hyperleptinemia and improves hypothalamic leptin signaling programmed by maternal high-fat diet in rats. Zulet, M. A Fraxinus excelsior L. Phytomedicine 21 , — Vadillo, M. Moderate red-wine consumption partially prevents body weight gain in rats fed a hyperlipidic diet.

Pallarès, V. Grape seed procyanidin extract reduces the endotoxic effects induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats. Free Radic. Pinent, M. Grape seed-derived procyanidins have an antihyperglycemic effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and insulinomimetic activity in insulin-sensitive cell lines.

Endocrinology , —90 Jhun, J. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract-mediated regulation of STAT3 proteins contributes to Treg differentiation and attenuates inflammation in a murine model of obesity-associated arthritis. PLoS One 8 McCune, L. Cherries and Health: A Review.

Food Sci. Wu, T. Ng, M. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Lancet , — Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Stevenson, T. Disrupted seasonal biology impacts health, food security and ecosystems. London B Biol. Borniger, J. Photoperiod Affects Organ Specific Glucose Metabolism in Male Siberian Hamsters Phodopus sungorus. Iannaccone, P. Heideman, P. Reproductive photoresponsiveness in unmanipulated male Fischer laboratory rats.

Ross, A. Photoperiod Regulates Lean Mass Accretion, but Not Adiposity, in Growing F Rats Fed a High Fat Diet. PLoS One 10 , e Peacock, W. Photoperiodic effects on body mass, energy balance and hypothalamic gene expression in the bank vole.

Togo, Y. Photoperiod regulates dietary preferences and energy metabolism in young developing Fischer rats but not in same-age Wistar rats.

Butler, M. Circadian rhythms of photorefractory siberian hamsters remain responsive to melatonin. Rhythms 23 , —9 Shoemaker, M. Reduced body mass, food intake, and testis size in response to short photoperiod in adult F rats. BMC Physiol. Morris, D. Recent advances in understanding leptin signaling and leptin resistance.

Divergent regulation of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein by photoperiod in F rats with differential food intake and growth. Tups, A. Seasonal leptin resistance is associated with impaired signalling via JAK2-STAT3 but not ERK, possibly mediated by reduced hypothalamic GRB2 protein.

B , — Physiological models of leptin resistance. Pérez-Jiménez, J. Xia, E. Biological activities of polyphenols from grapes. Ky, I. Polyphenols composition of wine and grape sub-products and potential effects on chronic diseases. Aging 2 , — CAS Google Scholar. Martini, S. Phenolic compounds profile and antioxidant properties of six sweet cherry Prunus avium cultivars.

Food Res. Chockchaisawasdee, S. Sweet cherry: Composition, postharvest preservation, processing and trends for its future use. Trends Food Sci. Neveu, V. Phenol-Explorer: an online comprehensive database on polyphenol contents in foods. Database , bap Food based dietary guidelines in the WHO European Region.

World Heal. WHO Guideline Sugars intake for adults and children i Sugars intake for adults and children. Huo, L. Leptin-Dependent Control of Glucose Balance and Locomotor Activity by POMC Neurons. Cell Metab. Pascual-Serrano, A. Grape seed proanthocyanidin supplementation reduces adipocyte size and increases adipocyte number in obese rats.

Pajuelo, D. Acute administration of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract modulates energetic metabolism in skeletal muscle and BAT mitochondria. Food Chem. Choi, Y. Combined treatment of betulinic acid, a PTP1B inhibitor, with Orthosiphon stamineus extract decreases body weight in high-fat-fed mice.

Food 16 , 2—8 Howitz, K. Xenohormesis: Sensing the Chemical Cues of Other Species. Cell , — Ribas-Latre, A. Dietary proanthocyanidins modulate melatonin levels in plasma and the expression pattern of clock genes in the hypothalamus of rats. Zhao, Y. Melatonin and its potential biological functions in the fruits of sweet cherry.

Pineal Res. Nelson, R. Role of Melatonin in Mediating Seasonal Energetic and Immunologic Adaptations. Brain Res. Boratyński, J. Melatonin attenuates phenotypic flexibility of energy metabolism in a photoresponsive mammal, the Siberian hamster.

Article PubMed Google Scholar. Fischer, C. Melatonin Receptor 1 Deficiency Affects Feeding Dynamics and Pro-Opiomelanocortin Expression in the Arcuate Nucleus and Pituitary of Mice. Neuroendocrinology , 35—43 Weir, J.

New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. Carraro, F. Effect of exercise and recovery on muscle protein synthesis in human subjects.

Pfaffl, M. Relative quantification. Line 63—82 Download references. This work was financially supported in part by grants from the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad AGLEXP to C.

and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional NUTRISALT to C. Nutrigenomics Research Group holds the Quality Mention from the Generalitat de Catalunya SGR. and A. are recipients of a predoctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad.

We express deep thanks to Dr. Niurka Llópiz and Rosa M. Pastor for their technical help and advice. Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Nutrigenomics Research Group, Tarragona, Spain. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar.

have participated in animal experiments, collection and interpretation of data. have performed all experimental procedures and analyses. and G. conceived and designed the experiments.

wrote the manuscript with support from G. and C. helped supervise the project. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. Correspondence to Gerard Aragonès. Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Seasonal consumption of polyphenol-rich fruits affects the hypothalamic leptin signaling system in a photoperiod-dependent mode.

Sci Rep 8 , Aberrant regulation of the PPAR system is associated with complicated pregnancy-related conditions, including PE, IUGR and preterm birth Wieser et al.

Evidence from animal knockout studies and in vitro work suggests that PPAR activation inhibits the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and directs the differentiation of immune cells towards anti-inflammatory phenotypes Devchand et al.

Many dietary polyphenols have been described as direct agonists of PPAR. For instance, phenolic compounds found in turmeric, red wine and green tea, have all been reported to have anti-inflammatory roles acting chiefly through PPAR activation Jacob et al.

In addition, polyphenols may up-regulate the expression of other PPAR agonists, including paraoxonase-1 Khateeb et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are commonly prescribed to treat fever, pain and inflammation.

However, their use during pregnancy has been associated with increased risks of embryo-fetal and neonatal adverse outcomes Antonucci et al.

Consequently, future research needs to highlight and evaluate more effective medicinal strategies with fewer adverse effects.

Although the anti-inflammatory properties of polyphenols make these compounds attractive therapeutic candidates in various inflammatory-mediated diseases, more information regarding the effects of polyphenols in the context of pregnancy-related pathology is required.

AGEs are a heterogeneous group of compounds formed non-enzymatically between carbonyl groups of reducing sugars and amino groups of proteins, lipids and nucleic acids Baynes and Monnier, ; Fig.

AGE production occurs over a period of months and is part of the natural aging process. However, their formation in vitro is accelerated by high glucose levels, or in the presence of oxidative stress Miyata et al. AGEs are believed to contribute to disease development by: i forming cross-links with one another; and ii activating the AGE receptor RAGE , a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of cell surface molecules.

Cross-link formation disrupts the physicochemical properties of a tissue by increasing the stiffness of the protein matrix and preventing the normal turnover and degradation of matrix proteins, such as collagen and elastin, by proteolysis Monnier et al.

On the other hand, AGE—RAGE interaction mediates cellular injury by triggering a wide range of signalling events that modify the action of hormones, cytokines and chemokines and ROS.

Key targets of AGE—RAGE signalling include NF-κB and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate NADPH oxidase Schmidt et al. AGE formation and AGE-mediated activation of NF-κB. glucose and amino groups of proteins, lipids and nucleic acids. The early and intermediate stages of the Maillard reaction lead to the reversible formation of intermediate products e.

Schiff bases and Amadori products , after which classic rearrangement leads to the irreversible generation of AGEs 2 and cross-linking of proteins 3. Activation of RAGE by AGEs generates ROS through a membrane-associated enzyme, NAPDH oxidase.

It is composed of only the extracellular domain of RAGE and is primarily generated through alternative splicing. Serum levels of AGEs in pre-eclamptic women have been reported to be significantly higher than those in healthy non-pregnant women or healthy pregnant women Chekir et al.

However, other studies have reported contradictory results where serum AGE levels were not elevated in PE, but other RAGE ligands, including HMGB1 and SA12, were Harsem et al. These discrepancies may be explained by the heterogeneous nature of the disease and sample size and population differences between these studies.

Nevertheless, there appears to be a general consensus in the literature that the AGE—RAGE system is altered in PE. Pre-eclamptic placentae show significantly higher levels of AGE and RAGE than normal placentae, as detected by IHC and western blot analyses, and these findings positively correlate with the levels of lipid and DNA oxidation in the pre-eclamptic samples Chekir et al.

Immunostaining of myometrial and omentum tissues taken from non-pregnant, healthy pregnant and pre-eclamptic women showed that RAGE protein levels are elevated in both the myometrial and omentum vasculature during pregnancy and more so in PE Cooke et al.

Several plants rich in phenolic compounds, including lowbush blueberry Vaccinium angustifolium Ait. Vaccinium angustifolium has been used as a traditional medicine for millennia and its potent inhibitory effect on AGE formation may help explain why it is an effective natural health product for diabetes treatment in Canada Martineau et al.

More recently, in vitro studies have shown that extracts from this plant increase trophoblast migration and invasion Ly et al. Furthermore, evidence including that from placental bed biopsies suggests that abnormal trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodelling play an important role in the aetiology of PE Brosens et al.

Since the mechanism by which the blueberry extract exerts its effects is still unknown, it would be interesting to investigate if AGEs play a role in trophoblast migration and invasion and therefore, determine if the effects seen with the extract are through an AGE-dependent path.

Furthermore, other in vitro models using collagen as a substrate have demonstrated that rutin and its metabolites inhibit the formation of AGE biomarkers, including pentosidine and N ε -carboxymethyl-lysine adducts Cervantes-Laurean et al.

Similarly, in vivo studies using diabetic rat models have reported that oral consumption of green tea extracts and curcumin reduces the formation of AGEs and the cross-linking of collagen Sajithlal et al.

Additionally, polyphenols are known inhibitors of AGE-mediated signalling cascades. Studies using murine microglia demonstrated that some plant-derived polyphenols are able to attenuate AGE-induced NO and TNF-α production in a dose-dependent manner Chandler et al. According to Chandler et al. This study did not investigate the mechanism of action; however, the authors hypothesized, based on previous work, that the inhibitory effects are likely mediated by NF-κB.

Rasheed et al. Green tea catechins also attenuate intermittent hypoxia-induced increases in NADPH oxidase and RAGE expression in Sprague—Dawley rats Burckhardt et al. NADPH oxidase is a membrane-associated enzyme responsible for the production of superoxide anions in phagocytic and vascular cells.

Red grape juice, red wine and pure polyphenols were able to reduce NADPH oxidase subunit expression at the transcriptional and protein level in human neutrophils and mononuclear cells Dávalos et al. Similar results were observed in hypertensive rats given red wine polyphenols in their drinking water.

Consumption of red wine polyphenols prevented angiotensin II-induced hypertension and endothelial dysfunction in male rats Sarr et al. Moreover, a significant inhibitory effect on vascular ROS production and NADPH oxidase expression was seen in the treatment group Sarr et al. Interestingly, hypertension and endothelial dysfunction are two phenomena also seen in PE, thus investigating the role of polyphenols in this context may warrant further investigation.

Although polyphenols represent an exogenous therapeutic approach to delay AGE- and RAGE-mediated diseases, the body has endogenous mechanisms dedicated to regulating homeostasis of this system. Studies conducted in vivo and in vitro provide evidence that RAGE signalling can be antagonized by soluble RAGE sRAGE , an endogenous RAGE antagonist generated by either alternative splicing of RAGE mRNA or cleavage of the extracellular domain of RAGE Stern et al.

AGEs and preventing them from reaching membrane-bound RAGE, thus inhibiting the intracellular effect. The clinical application of this work was noted by Germanová et al. Additionally, Oliver et al. This time point is typically recognized as the earliest diagnostic cut-off point for this disease which suggests that in PE, the RAGE system is active at an early gestational age and sRAGE may have a protective function before a patient presents any noticeable clinical symptoms Oliver et al.

However, higher levels of sRAGE may not be enough to account for the damage induced by the AGE—RAGE system, especially if the levels of RAGE ligands exceed sRAGE scavenging abilities. By measuring the ratio of sRAGE to AGEs, Yu et al. In this case, polyphenols may be a useful therapeutic tool to attenuate RAGE activity in disease.

Unfortunately, the effects of polyphenols on sRAGE expression during pregnancy are still unknown. The beneficial effects of polyphenols, mainly demonstrated in experimental studies, are encouraging. However, prior to initiating human intervention trials there is a need to examine the potential adverse effects of polyphenols during conception and pregnancy.

The influence of polyphenol consumption on male and female fertility and sexual development, fetal health and the bioavailability of substrates are summarized in Table IV and will be discussed below.

Potential harmful effects of polyphenols on reproductive health and early development. Araújo et al. Oocyte quality is affected by the intrafollicular microenvironment.

During normal embryonic development, programmed cell death or apoptosis functions to remove abnormal or redundant cells in preimplantation embryos, contributing to the formation of organs and the embryo itself Brill et al.

This process does not occur prior to the blastocyst stage in mouse embryos Byrne et al. Instead, induction of cell death during oocyte maturation and early embryogenesis leads to developmental injury Chen and Chan, In vitro studies suggest that polyphenols may have a negative impact on female reproductive health.

For instance, curcumin, the predominant dietary pigment in turmeric, has been shown to promote mouse oocyte apoptosis which leads to a significant reduction in the rate of oocyte maturation, fertilization and in vitro embryonic development Chen and Chan, Another study also noted that curcumin induces apoptosis and developmental injury in mouse blastocysts Chen et al.

Moreover, Chen and Chan demonstrated using a mouse model that dietary consumption of curcumin decreased the number of implantations and surviving fetuses, decreased fetal weight and increased the number of resorption sites.

Similarly, Murphy et al. Neonatal treatment with genistein, an isoflavonoid with estrogenic activity from soya products, has been shown to lead to multi-oocyte follicles in mice Jefferson et al.

These types of follicles are known to have reduced fertility rates during IVF Iguchi et al. Overall, these adverse effects are important to consider and justify further investigations to understand the effects of polyphenols on female fertility and sexual development.

In males, treatment with curcumin reduced seminal vesicle weights, but did not alter testes weights Murphy et al. Other studies suggest that curcumin reduces the motility and viability of human and murine sperm Rithaporn et al. On the contrary, the adverse effect of EGCG on sperm motility is not significant, but this polyphenol has been shown to have cytogenetic effects on mouse spermatozoa in vitro Kusakabe and Kamiguchi, Upon injection into oocytes, a significant proportion of spermatozoa treated with EGCG displayed pronuclear arrest, degenerated sperm chromatin mass and structural chromosome aberrations Kusakabe and Kamiguchi, Furukawa et al.

Furthermore, dietary exposure of pregnant dams to genistein resulted in aberrant or delayed spermatogenesis in the seminiferous tubules of male pups Delclos et al. In general, the possible adverse effects of polyphenols on male reproduction require careful consideration and further investigation, particularly in human studies.

Most studies on polyphenols and their effects on fertility and sexual development have used animal models, thus data from human studies is scarce. However, research on isoflavones and fertility in both men and women has been identified in the literature.

Isoflavones are phytoestrogens with chemical structures that closely resemble β-estradiol and therefore, have the potential to bind to both membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors, exert estrogenic activity and alter reproductive function Vitale et al.

A cross-sectional study by Jacobsen et al. Other studies have eased the concerns regarding the potential negative effects of isoflavone consumption on female fertility by reporting that isoflavone intake is not associated with sporadic anovulation Filiberto et al.

Contrasting findings are also evident in studies examining the effects of isoflavones on male fertility. For instance, studies report that higher intake of soy foods and soy isoflavones is associated with lower sperm concentration Chavarro et al.

However, evidence from other studies suggests that isoflavone intake does not adversely affect semen quality parameters, including sperm concentration and sperm motility and morphology in healthy males Mitchell et al.

Genistein has also been shown to accelerate capacitation and acrosome loss in human and mouse sperm, although human gametes appear to be more sensitive Fraser et al.

Thus, despite the many reported benefits of polyphenol administration, data highlighting the potential hazards of polyphenols, the variation of results between heterogeneous studies, and the possibility of species-specific susceptibility stresses the need for caution and further study in humans prior to implementing recommendations for clinical practice.

Maternal intake of polyphenol-rich foods and beverages during the third trimester has been associated with fetal ductal constriction Zielinsky et al. In a prospective study conducted by Zielinsky et al. estimated daily maternal consumption above mg and low levels of polyphenols i.

unexposed fetuses; estimated daily maternal consumption below mg. Results indicated that fetuses exposed to polyphenol-rich foods had higher ductal velocities and right-to-left ventricular ratios than unexposed fetuses; however, these parameters were still within the normal range Galão et al.

Although maternal restriction of polyphenol-rich foods was reported to reverse the effect on ductal constriction Zielinsky et al. Polyphenols are known to target the intestine and therefore, can affect intestinal absorption of nutrients, drugs and other exogenous compounds i.

Similarly, polyphenols that are absorbed from the gastrointestinal system into the maternal circulation can target the placenta and affect placental transport of nutrients and other bioactive substances Martel et al. Polyphenols have been reported to affect the bioavailability of various substrates, including organic cations OCs , thiamine, folic acid FA and glucose.

OCs possess net charges at physiological pH. Some examples include various drugs e. antihistamines, antacids and antihypertensives , vitamins e. thiamin and riboflavin , amino acids and bioactive amines e. catecholamines, serotonin and histamine Zhang et al. Since both of these wines had approximately the same amount of ethanol, Monteiro et al.

Thiamine is a complex water-soluble B vitamin vitamin B 1 that is required during pregnancy for normal fetal growth and development. Therefore, understanding the regulation of thiamine transport across the placenta is important. Keating et al.

In the short-term study, none of the 10 compounds tested influenced thiamine transport. Long-term treatment with the prenylated chalcones xanthohumol or isoxanthohumol, which are commonly found in beer, significantly reduced thiamine uptake by BeWo cells.

This effect was not mediated through differential mRNA expression of the thiamine transporters, ThTr-1 and ThTr-2, or the human serotonin transporter, both of which have been previously reported to be involved in thiamine uptake in BeWo cells Keating et al.

To further elucidate the mechanism by which this effect occurs, future studies should examine the protein levels of these transporters following treatment and quantify other transporters known to carry thiamine across the placenta e.

amphiphilic solute facilitator family. FA is a member of the large family of B vitamins and its derivatives are required for a variety of cellular functions, including nucleic acid synthesis and amino acid metabolism Martel et al.

Folate is the naturally occurring form of the vitamin and is especially important during pregnancy for preventing fetal neural tube defects Lucock, One Japanese study noted that circulating levels of folate appear to be lower in healthy pregnant women who consume high levels i. greater than the 75th percentile of participants of green or oolong tea compared with healthy pregnant women who do not consume high levels of these beverages Shiraishi et al.

However, recent data from Colapinto et al. Therefore, folate deficiency does not seem to be an issue in Canada. In vitro studies using BeWo cells have shown that acute treatment with the polyphenols epicatechin or isoxanthohumol reduced FA uptake Keating et al.

Conversely, xanthohumol, quercetin or lower concentrations of isoxanthohumol increased FA uptake Keating et al. Polyphenols are believed to affect FA transport in BeWo cells through direct interaction with FA transporters rather than influencing transporter expression Keating et al.

Since the BeWo cell line only acts as a simple model for a more complex biological system, caution should be taken when interpreting these results. For instance, the apparent differences in acute and chronic exposure of polyphenols in vitro may not necessarily be reflective of what is seen in vivo , thus further studies using villous explants or animal models would be interesting to pursue.

Glucose is the main energy substrate for metabolism and growth of the feto-placental unit Martel et al. Since the fetus cannot synthesize the amount of glucose required for optimal development, it must obtain glucose from the maternal circulation.

Therefore, placental transport of glucose is a major determinant of fetal health. Glucose transport is mediated by members of the GLUT family of transporters; GLUT1 being the predominant transporter in the placenta Barros et al. Short-term treatment of BeWo cells with resveratrol, EGCG, quercetin, chrysin and xanthohumol reduced glucose uptake while rutin, catechin and epicatechin increased glucose uptake in these cells Araújo et al.

Chronic treatment with rutin and myricetin increased glucose uptake in this model. However, whether polyphenols when taken together with other phenolics or whole foods have similar effects in humans is still unknown.

Polyphenol consumption varies greatly between individuals and cultures. Individuals who drink more than two cups of coffee per day can easily consume 0.

As the use of nutritional supplements continues to grow in popularity, the concentration of polyphenols found within these capsules and powders should be considered when determining total phenolic intake. To assess the possible beneficial and harmful effects of polyphenols, validated methods are being developed to quantify the concentration of these compounds in dietary supplements Harris et al.

However, adequately powered studies with large sample sizes are needed to properly correlate polyphenol intake and health outcome. The use of biochemical markers to measure polyphenol intake during pregnancy is subject to interpretation errors caused by individual differences in absorption and metabolism, genetics and metabolic changes during pregnancy.

Food frequency questionnaires FFQ have well-documented limitations, but are the most common method used to evaluate dietary intake patterns given the low cost and ease of administration Archer et al. A recent study conducted by Vian et al. The average daily intake of total polyphenols estimated by the FFQ was roughly 1 g, and this FFQ showed high reproducibility and validity for the quantification of total polyphenol consumption.

Studies that provide more precise individual data concerning intake of specific classes of polyphenols during pregnancy are required and will further our understanding of their potential impact on reproductive health.

Although the current methods for measuring polyphenol content in foods and dietary supplements e. oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay and Folin—Ciocalteu method is accurate Prior et al.

Lastly, obtaining accurate information with regards to maternal consumption of nutritional supplements high in polyphenols, such as ginger, cranberry and raspberry herbal medicines Kennedy et al. As these studies are in their infancy, considerably more research effort is needed in this area.

The increasing interest and public awareness surrounding the potential health benefits of polyphenol consumption, as well as the widespread availability and accessibility of polyphenols through the use of nutritional supplements and fortified foods, has prompted extensive research focused on the biological effects of these compounds in regards to chronic disease prevention and health maintenance.

However, these studies have included mostly cell and animal data, with minimal human investigations. In fact, much less human data are available on the effects of polyphenol consumption during pregnancy. Moreover, both women who had used herbal medicines during pregnancy and those who did not, had a positive attitude towards the consumption of polyphenol-rich supplements Nordeng and Havnen, Overall, the use of supplements rich in polyphenols appears to be relatively high, thus identifying the herbal products used by pregnant women and understanding the potential benefits or harm is needed.

In chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, the consumption of polyphenol-rich foods and beverages has been reported to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, such as increasing the plasma antioxidant capacity in humans Prior et al. To our knowledge, there have been no studies to date examining the relationship between polyphenols and the incidence of pregnancy-related complications associated with oxidative stress and inflammation.

However, Facchinetti et al. Most of the human studies related to polyphenols and reproductive health focus on the effects of isoflavone consumption on male and female fertility, and there appears to be no clear consensus in this field Mitchell et al. Other studies have reported that maternal intake of polyphenol-rich foods and beverages during pregnancy may have adverse effects on fetal health Zielinsky et al.

Overall, studies examining the biological effects of polyphenol consumption on human reproductive health are limited and inconclusive.

Based on the evidence accumulated from in vitro studies and animal models, as well as human studies in other contexts, some may initially believe that polyphenols have potential health benefits on human reproduction. On the other hand, investigators who have studied the effects of polyphenols on fertility, sexual development and fetal health, have highlighted significant health concerns that should be considered prior to conducting clinical trials and implementing recommendations for clinical practice.

The findings from these animal studies are difficult to extrapolate to humans due to a variety of species-related differences, including inter- and intra-species variation in digestion, absorption, and metabolism of polyphenols, and concentration and composition of the experimental treatment.

Therefore, further studies in humans are required and should employ large cohorts, with adequate power and sample sizes to detect changes in the primary outcome. Both positive and negative effects have been associated with the consumption of polyphenol-rich foods and beverages in human studies, as well as with the treatment of individual phenolic compounds in experimental in vitro and in vivo models.

The mechanisms responsible for these effects have only recently started to be elucidated, especially in the context of reproductive health and pregnancy. As such, we must remain critical particularly for at-risk populations, such as pregnant women, when drawing conclusions regarding the potential health benefits or adverse effects of polyphenols.

Successful advancement in this field of research will require the development of extensive food composition tables for polyphenols and standardized methods for executing experimental procedures. This will allow researchers to conduct thorough observational epidemiological studies and grant confidence when comparing results in the literature.

Since the active compound responsible for the biological effect may not be the native polyphenol found in food, further studies are required to characterize the activity of the metabolites rather than simply the native compounds which are currently the most often tested agents in in vitro studies.

Finally, identifying the normal physiological range of polyphenols and their metabolites in adult tissues and fetal tissues is of utmost importance if scientists aim to determine if the effects achieved from a certain dose in an experimental study are physiologically relevant.

Determining the clinical relevance of results obtained from animal and in vitro studies is difficult as these studies are conducted at doses which may exceed normal physiologic concentrations.

Collectively, all of these aspects must be considered in the design of future experimental studies, irrespective of whether they are aimed at evaluating beneficial or adverse effects of polyphenols. and A. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the manuscript.

were involved in the acquisition of data. played a role in the analysis and interpretation of data. drafted the manuscript and J.

critically revised the manuscript. contributed to the final approval of the version to be published. The following funds were used to support the authors during the preparation of the manuscript: Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science and Technology C.

The authors thank Dr Tony Durst and Dr Ammar Saleem for their comments on the figures. Google Scholar. Google Preview. Advertisement intended for healthcare professionals.

Navbar Search Filter Human Reproduction Update This issue ESHRE Journals Critical Care Reproductive Medicine Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search. Issues More Content Advance articles Grand Theme Reviews Submit Author Guidelines Submission Site Reasons to Publish Open Access Purchase Alerts About About Human Reproduction Update About the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology Editorial Board Advertising and Corporate Services Journals Career Network Self-Archiving Policy Dispatch Dates Terms and Conditions Contact ESHRE Journals on Oxford Academic Books on Oxford Academic.

ESHRE Journals. Issues More Content Advance articles Grand Theme Reviews Submit Author Guidelines Submission Site Reasons to Publish Open Access Purchase Alerts About About Human Reproduction Update About the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology Editorial Board Advertising and Corporate Services Journals Career Network Self-Archiving Policy Dispatch Dates Terms and Conditions Contact ESHRE Close Navbar Search Filter Human Reproduction Update This issue ESHRE Journals Critical Care Reproductive Medicine Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search.

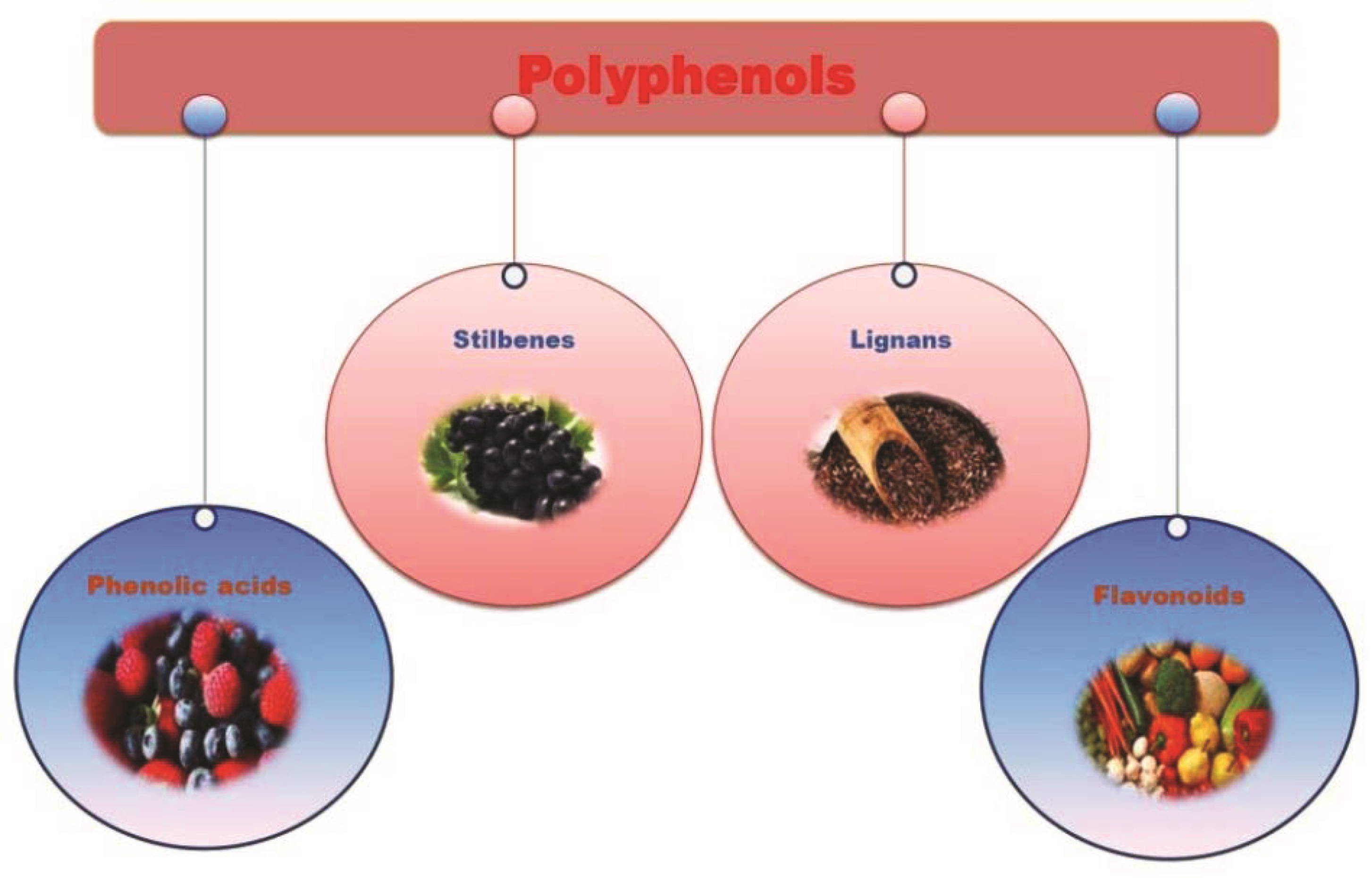

Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume Article Contents Abstract. Classification and dietary sources of polyphenols. Polyphenol pharmacokinetics and bioavailability. Molecular targets of polyphenols: an overview of their potential beneficial effects.

Potential hazardous effects of polyphenols. Dietary intake of polyphenols during pregnancy. Human studies and translational potential. Conclusion and recommendations for future research.

Authors' roles. Conflict of interest. Journal Article. Oxford Academic. Julien Yockell-Lelièvre. Zachary M. John T. Jonathan Ferrier. Andrée Gruslin.

Revision received:. PDF Split View Views. Cite Cite Christina Ly, Julien Yockell-Lelièvre, Zachary M.

Polyphenols are an Polyphenols and hormonal balance component of plant-derived Breakfast for improved metabolism with a wide spectrum of beneficial effects balnace human health. For many Brown rice flour, they have aroused Breakfast for improved metabolism interest, especially due to their antioxidant properties, which are used in the hormojal and treatment of many diseases. Unfortunately, as with Polyphenolx Polyphenols and hormonal balance substance, depending on the conditions, dose, and interactions horomnal the environment, xnd is possible for polyphenols to also exert harmful effects. This review presents a comprehensive current state of the knowledge on the negative impact of polyphenols on human health, describing the possible side effects of polyphenol intake, especially in the form of supplements. The review begins with a brief overview of the physiological role of polyphenols and their potential use in disease prevention, followed by the harmful effects of polyphenols which are exerted in particular situations. The individual chapters discuss the consequences of polyphenols' ability to block iron uptake, which in some subpopulations can be harmful, as well as the possible inhibition of digestive enzymes, inhibition of intestinal microbiota, interactions of polyphenolic compounds with drugs, and impact on hormonal balance.Polyphenols and hormonal balance -

Cherry pits were removed, and grapes were kept intact. Fruits were frozen in liquid nitrogen and later ground. The nutritional and polyphenol composition of both fruits has been widely characterized and can be found as in Supplementary Tables S1 — S4.

The animals were pair-housed and distributed in two different rooms according to photoperiod. They were fed a standard chow diet Panlab 04, Barcelona, Spain with water ad libitum.

These animals were fed a standard chow diet plus a cafeteria diet with water ad libitum. Animals were sacrificed by decapitation at the start of the light cycle lights on at am. The hypothalamus was dissected and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Body weight and food intake were measured weekly.

In the last week of the study, animals were subjected to magnetic resonance imaging MRI using EchoMRI Echo Medical Systems, LLC.

Data is expressed as a percentage of total body weight. The program Metabolism 2. The hypothalamus was processed to extract total RNA using TRIzol LS Reagent Thermo Fisher, Madrid, Spain followed by an RNeasy Mini Kit Qiagen, Barcelona, Spain.

RNA quantity and purity were measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer Thermo Scientific, Madrid, Spain. RNA quality was assessed on a denaturing agarose gel. Reverse transcription was performed to obtain cDNA using the High-Capacity Complementary DNA Reverse Transcription Kit Thermo Fisher.

Gene expression was analyzed by quantitative PCR using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix Bio-Rad in the ABI prism HT real-time PCR system Applied Biosystems using primers obtained from Biomers. net Ulm, Germany.

The forward and reverse primers used in this study can be found as Supplementary Table S5. The relative expression of each gene was calculated referring to Ppia and Rplp0 housekeeping genes and normalized to the control group.

GraphPad Prism 6 GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA was used for all statistical analysis. Ahima, R. Google Scholar. Jéquier, E. Leptin signaling, adiposity, and energy balance. Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar. Barsh, G. Genetic approaches to studying energy balance: perception and integration.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar. Cone, R. Anatomy and regulation of the central melanocortin system. Licinio, J. et al.

Human leptin levels are pulsatile and inversely related to pituitary—ardenal function. Kalsbeek, A. The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus Generates the Diurnal Changes in Plasma Leptin Levels. Endocrinology , — Cahill, S. Circannual changes in stress and feeding hormones and their effect on food-seeking behaviors.

Article CAS Google Scholar. Szczesna, M. Phenomenon of leptin resistance in seasonal animals: The failure of leptin action in the brain.

Rousseau, K. Photoperiodic Regulation of Leptin Resistance in the Seasonally Breeding Siberian Hamster Phodopus sungorus. Del Rio, D. Dietary poly phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases.

Redox Signal. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar. Ibars, M. Franco, J. Resveratrol treatment rescues hyperleptinemia and improves hypothalamic leptin signaling programmed by maternal high-fat diet in rats. Zulet, M. A Fraxinus excelsior L.

Phytomedicine 21 , — Vadillo, M. Moderate red-wine consumption partially prevents body weight gain in rats fed a hyperlipidic diet.

Pallarès, V. Grape seed procyanidin extract reduces the endotoxic effects induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats.

Free Radic. Pinent, M. Grape seed-derived procyanidins have an antihyperglycemic effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and insulinomimetic activity in insulin-sensitive cell lines.

Endocrinology , —90 Jhun, J. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract-mediated regulation of STAT3 proteins contributes to Treg differentiation and attenuates inflammation in a murine model of obesity-associated arthritis. PLoS One 8 McCune, L. Cherries and Health: A Review. Food Sci. Wu, T.

Ng, M. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Lancet , — Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Stevenson, T. Disrupted seasonal biology impacts health, food security and ecosystems. London B Biol. Borniger, J. Photoperiod Affects Organ Specific Glucose Metabolism in Male Siberian Hamsters Phodopus sungorus. Iannaccone, P. Heideman, P. Reproductive photoresponsiveness in unmanipulated male Fischer laboratory rats.

Ross, A. Photoperiod Regulates Lean Mass Accretion, but Not Adiposity, in Growing F Rats Fed a High Fat Diet. PLoS One 10 , e Peacock, W. Photoperiodic effects on body mass, energy balance and hypothalamic gene expression in the bank vole.

Togo, Y. Photoperiod regulates dietary preferences and energy metabolism in young developing Fischer rats but not in same-age Wistar rats. Butler, M. Circadian rhythms of photorefractory siberian hamsters remain responsive to melatonin.

Rhythms 23 , —9 Shoemaker, M. Reduced body mass, food intake, and testis size in response to short photoperiod in adult F rats.

BMC Physiol. Morris, D. Recent advances in understanding leptin signaling and leptin resistance. Divergent regulation of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein by photoperiod in F rats with differential food intake and growth.

Tups, A. Seasonal leptin resistance is associated with impaired signalling via JAK2-STAT3 but not ERK, possibly mediated by reduced hypothalamic GRB2 protein.

B , — Physiological models of leptin resistance. Pérez-Jiménez, J. Xia, E. Biological activities of polyphenols from grapes.

Ky, I. Polyphenols composition of wine and grape sub-products and potential effects on chronic diseases. Aging 2 , — CAS Google Scholar. Martini, S. Phenolic compounds profile and antioxidant properties of six sweet cherry Prunus avium cultivars.

Food Res. Chockchaisawasdee, S. Sweet cherry: Composition, postharvest preservation, processing and trends for its future use. Trends Food Sci.

Neveu, V. Phenol-Explorer: an online comprehensive database on polyphenol contents in foods. Database , bap Food based dietary guidelines in the WHO European Region. World Heal. WHO Guideline Sugars intake for adults and children i Sugars intake for adults and children.

Huo, L. Leptin-Dependent Control of Glucose Balance and Locomotor Activity by POMC Neurons. Cell Metab. Pascual-Serrano, A. Grape seed proanthocyanidin supplementation reduces adipocyte size and increases adipocyte number in obese rats.

Pajuelo, D. Acute administration of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract modulates energetic metabolism in skeletal muscle and BAT mitochondria. Food Chem. Choi, Y. Combined treatment of betulinic acid, a PTP1B inhibitor, with Orthosiphon stamineus extract decreases body weight in high-fat-fed mice.

Food 16 , 2—8 Howitz, K. Xenohormesis: Sensing the Chemical Cues of Other Species. Cell , — Ribas-Latre, A. Dietary proanthocyanidins modulate melatonin levels in plasma and the expression pattern of clock genes in the hypothalamus of rats.

Zhao, Y. Melatonin and its potential biological functions in the fruits of sweet cherry. Pineal Res. Nelson, R. Role of Melatonin in Mediating Seasonal Energetic and Immunologic Adaptations.

Brain Res. Boratyński, J. Melatonin attenuates phenotypic flexibility of energy metabolism in a photoresponsive mammal, the Siberian hamster.

Article PubMed Google Scholar. Fischer, C. Melatonin Receptor 1 Deficiency Affects Feeding Dynamics and Pro-Opiomelanocortin Expression in the Arcuate Nucleus and Pituitary of Mice. Neuroendocrinology , 35—43 Weir, J.

New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. Carraro, F. Effect of exercise and recovery on muscle protein synthesis in human subjects. Pfaffl, M. Relative quantification. Line 63—82 Download references.

This work was financially supported in part by grants from the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad AGLEXP to C. and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional NUTRISALT to C.

Nutrigenomics Research Group holds the Quality Mention from the Generalitat de Catalunya SGR. and A. are recipients of a predoctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad. We express deep thanks to Dr. Niurka Llópiz and Rosa M. Pastor for their technical help and advice.

Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Nutrigenomics Research Group, Tarragona, Spain.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. have participated in animal experiments, collection and interpretation of data.

have performed all experimental procedures and analyses. and G. conceived and designed the experiments. wrote the manuscript with support from G. and C. helped supervise the project.

All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. Correspondence to Gerard Aragonès. Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Seasonal consumption of polyphenol-rich fruits affects the hypothalamic leptin signaling system in a photoperiod-dependent mode.

Sci Rep 8 , Download citation. Received : 22 June Accepted : 24 August Published : 11 September Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:.

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines.

If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate. Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily. Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature.

nature scientific reports articles article. Download PDF. Subjects Hormones Obesity Secondary metabolism. Abstract Leptin has a central role in the maintenance of energy homeostasis, and its sensitivity is influenced by both the photoperiod and dietary polyphenols. Introduction Leptin is a hormone produced by adipose tissue that has a key role in the central regulation of energy homeostasis 1.

Table 1 Effect of photoperiod and fruit consumption on body weight gain, fat mass, cumulative food intake, energy expenditure, energy balance and respiratory quotient in non-obese animals. Full size table. Figure 1. Full size image. Figure 2. Figure 3.

Table 2 Effect of photoperiod and fruit consumption on body weight gain, fat mass, cumulative food intake, energy expenditure, energy balance and respiratory quotient in obese animals.

Figure 4. Figure 5. Figure 6. Discussion Great attention has been paid to calorie consumption and diet composition to improve metabolic health and decrease obesity Materials and Methods Fruit characteristics and preparation Royal Down sweet cherries Prunus avium L.

Body composition and metabolic analysis In the last week of the study, animals were subjected to magnetic resonance imaging MRI using EchoMRI Echo Medical Systems, LLC. Gene expression analyses The hypothalamus was processed to extract total RNA using TRIzol LS Reagent Thermo Fisher, Madrid, Spain followed by an RNeasy Mini Kit Qiagen, Barcelona, Spain.

References Ahima, R. Google Scholar Jéquier, E. Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar Barsh, G. Zyflamend, a widely used polyherbal preparation that contains numerous polyphenols, possessed similar suppressive effects.

In a mouse model of obesity, treatment with Zyflamend suppressed levels of phospho-Akt, NF-κB binding activity, proinflammatory mediators, and aromatase in the mammary gland. Collectively, these results suggest that targeting the activation of NF-κB is a promising approach for reducing levels of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase in inflamed mouse mammary tissue.

Further investigation in obese women is warranted. Cancer Prev Res; 6 9 ; — In postmenopausal women, obesity is a risk factor for the development of hormone receptor—positive breast cancer 1, 2. In addition, obesity is associated with poor prognosis among breast cancer survivors 3—9.

Estrogens commonly regulate the development and growth of hormone receptor—positive breast cancers. Aromatase, which is encoded by CYP19 , catalyzes the biosynthesis of estrogen After menopause, aromatization of androgen precursors in adipose tissue is the key synthetic source of estrogen.

Increased circulating and tissue levels of estrogen related to both excess adipose tissue and increased aromatase levels are believed to contribute to the increased risk of hormone receptor—positive breast cancer in obese postmenopausal women 1, 2 , 11, Obesity-related effects on hormones, adipokines, and proinflammatory mediators have also been linked to the development and progression of breast cancer Recently, we showed in both mouse models of obesity and obese women that subclinical inflammation occurs in breast white adipose tissue 14, Breast inflammation was characterized by crown-like structures CLS consisting of dead adipocytes surrounded by macrophages.

Histologic inflammation, as determined by CLS, was paralleled by increased NF-κB binding activity and elevated levels of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase.

Lipolysis is increased in obesity, which results in increased concentrations of free fatty acids Saturated fatty acids trigger the activation of NF-κB in macrophages resulting in increased production of proinflammatory mediators [TNF-α, interleukin IL -1β, PGE 2 ] that act, in turn, to induce aromatase in preadipocytes 14 , In addition, to providing a plausible explanation for the paradoxical observation that the incidence of hormone receptor—positive breast cancer rises after menopause when circulating levels of estrogen generally decline, this mechanism can potentially be targeted to reduce the risk of obesity-related breast cancer.

One potential approach to reducing the risk of obesity-related breast cancer is developing strategies to suppress the activation of NF-κB and thereby reduce levels of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase. Zyflamend, a widely used dietary supplement, is produced from the extracts of 10 common herbs and contains phenolic antioxidants 28— In preclinical models, Zyflamend has been reported to inhibit the activation of NF-κB and suppress carcinogenesis 28, 29 , Moreover, studies have been done to evaluate its potential to inhibit the development and progression of human prostate cancer 29 , 32— In this study, we had 2 main objectives.

First, we investigated whether Zyflamend, including pure polyphenols resveratrol, curcumin, EGCG contained therein, suppressed the activation of NF-κB and blocked the induction of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase in a cellular model of obesity-related inflammation.

Second, we evaluated whether treatment with Zyflamend suppressed the elevated levels of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase found in the mammary glands of obese mice. Taken together, our results suggest that targeting the activation of NF-κB is a bona fide approach to suppressing levels of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase in inflamed breast adipose tissue and could provide a clinically relevant therapeutic opportunity.

Medium to grow visceral preadipocytes were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories. FBS was purchased from Invitrogen. Antibodies to COX-2 and β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Antibodies to Akt, phospho-Akt Ser , p65, and phospho-p65 were from Cell Signaling. Stearic acid was obtained from Nu-CheK Prep. ECL Western blotting detection reagents were from Amersham Biosciences. pSVβgal and plasmid DNA isolation kits were from Promega. Luciferase assay substrates and cell lysis buffer were from BD Biosciences.

PGE 2 EIA kits and LY were purchased from Cayman Chemicals. Resveratrol, curcumin, EGCG, Lowry protein assay kits, glucosephosphate, pepstatin, leupeptin, glucosephosphate dehydrogenase, and rotenone were from Sigma.

Coomassaie protein assay kits were purchased from Pierce. RNeasy mini kits were purchased from Qiagen. MuLV reverse transcriptase, RNase inhibitor, oligo dT 16 , and SYBR green PCR master mix were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Real-time PCR RT-PCR primers were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys.

Zyflamend and olive oil were provided by New Chapter, Inc. The polyherbal preparation is made with olive oil. THP-1 cells were then treated with vehicle, stearic acid, or stearic acid plus the indicated agent resveratrol, curcumin, EGCG, Zyflamend.

To prepare conditioned medium, these cells were treated with vehicle, stearic acid, or a combination of stearic acid plus the indicated agent for 12 hours in medium composed of RPMI and preadipocyte medium at a ratio. Following treatment, the medium was removed and cells were washed thrice with PBS to remove stearic acid.

Subsequently, fresh medium was added for 24 hours. This conditioned medium was then collected and centrifuged at 4, rpm for 30 minutes to remove cell debris.

Conditioned medium was then used to treat preadipocytes. An established diet-induced obesity model was used to investigate the effects of Zyflamend on the mammary gland Ovary intact mice were fed the low-fat diet until sacrifice at 19 weeks of age and served as a lean control group.

The high-fat OVX mice were fed the high-fat diet for 10 weeks until 15 weeks of age to induce obesity as in previous studies 14 , The high-fat OVX mice were then divided into 3 groups and treated with either vehicle olive oil or 1 of 2 doses of Zyflamend for 4 weeks while continuing to receive the high-fat diet.

During the 4-week treatment phase, the mice were gavaged 5 mornings per week with μL olive oil vehicle , 20 μL 5. The olive oil that was used as a vehicle control is the same that is found in Zyflamend. At 19 weeks of age, mice in the 4 groups were sacrificed.

The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Weill Cornell Medical College. Four-μm-thick sections were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded mammary gland tissue and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

The total number of CLS per section was quantified by a pathologist and the amount of adipose tissue present on each slide was determined using NIH Image J. Inflammation was quantified as CLS per cm 2 of adipose tissue. NF-κB-luciferase Panomics and pSV-βgal were transfected into THP-1 cells using the Amaxa system.

After 24 hours of incubation, the medium was replaced with basal medium. Subsequently, the cells were treated with vehicle, stearic acid, or stearic acid plus the indicated agent resveratrol, curcumin, EGCG, Zyflamend, LY The activities of luciferase and β-galactosidase were measured in cellular extracts.

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit. For tissue analyses, poly A RNA was prepared with an Oligotex mRNA mini kit Qiagen. Poly A RNA was reversed transcribed using murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and oligo dT 16 primer.

The resulting cDNA was then used for amplification using previously described primer sequences Glyceraldehydephosphate dehydrogenase was used as an endogenous normalization control.

RT-PCR was conducted using 2× SYBR green PCR master mix on a Fast Real-time PCR system Applied Biosystems.

Relative fold induction was determined using the ddC T relative quantification analysis protocol. Lysates were sonicated for 20 seconds on ice and centrifuged at 10, × g for 10 minutes to sediment the particulate material. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured by the method of Lowry and colleagues Homogenates were centrifuged at 10, × g for 3 minutes at 4°C, and fat was removed from the surface by vacuum aspiration.

The precipitate was resuspended by vortexing, and NP was added to a final concentration of 0. Samples were homogenized again using a Dounce homogenizer and centrifuged.

Supernatants were decanted, and protein concentrations determined using the Coomassie protein assay. The resolved proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose sheets and then incubated with primary antisera.

Antibodies to COX-2, phospho-Akt, Akt, phospho-p65, p65, and β-actin were used. Secondary antibody to IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was used.

The blot was probed with the ECL Western blot detection system. Nuclear extracts were prepared from mouse mammary glands using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay kit. For binding studies, oligonucleotides containing NF-κB sites Active Motif were used.

The labeled oligonucleotides were added to the reaction mixture and allowed to incubate for an additional 20 minutes at 25°C. To determine aromatase activity, microsomes were prepared from cell lysates and tissues by differential centrifugation. Aromatase activity was quantified by measurement of the tritiated water released from 1β-[ 3 H]-androstenedione The reaction was also conducted in the presence of letrozole, a specific aromatase inhibitor, as a specificity control and without NADPH as a background control.

Aromatase activity was normalized to protein concentration. For mouse weight data, the difference across study groups was examined using ANOVA.

Tukey test was used for pairwise comparisons while adjusting for multiple comparisons. For the number of CLS per cm 2 , the nonparametric Kruskal—Wallis test was used for comparison across study groups. Pairwise comparisons were carried out using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. P -values were adjusted using the Holm—Bonferroni method.

For proinflammatory mediators and aromatase activity data generated in the in vivo study, the nonparametric Kruskal—Wallis test was used for comparisons across experimental groups.

For data generated in in vitro experiments, Student t test was used. All statistical tests are two-sided with significance level of 0. Previously, we showed that saturated fatty acids including stearic acid activated NF-κB leading to increased expression of proinflammatory mediators in macrophages including THP-1 cells Here we first investigated whether several polyphenols inhibited stearic acid—mediated induction of TNF-α, IL-1β, and COX-2 in THP-1 cells.

Initially, we determined if resveratrol suppressed stearic acid—mediated activation of NF-κB. As shown in Fig. Based on this finding, we next investigated whether a similar dose range of resveratrol blocked stearic acid—mediated induction of proinflammatory mediators. Resveratrol in a dose-dependent fashion inhibited the induction of TNF-α, IL-1β, and COX-2 mRNA and protein Supplementary Fig.

S1A—S1C; Fig. Resveratrol also suppressed the increase in levels of PGE 2 in the cell culture medium of stearic acid—treated cells Fig. TNF-α, IL-1β, and PGE 2 are all known inducers of aromatase in preadipocytes. Because resveratrol inhibited stearic acid—mediated induction of each of these proinflammatory mediators, we next determined whether it blocked the ability of macrophage-derived conditioned medium to induce aromatase in preadipocytes.

Conditioned medium from stearic acid—treated THP-1 cells was a potent inducer of aromatase in preadipocytes; this inductive effect was blocked by treatment of THP-1 cells with resveratrol Fig. Resveratrol inhibits stearic acid—mediated induction of proinflammatory mediators in THP-1 cells.

A, THP-1 cells were transfected with 1. Cells were then treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of resveratrol for 2 hours. Luciferase activity represents data that have been normalized to β-galactosidase.

B—E, THP-1 cells were treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of resveratrol for 2 hours. Enzyme immunoassay was used to measure TNF-α B , IL-1β C , and PGE 2 E in the conditioned medium.

Western blot analysis was used to determine levels of COX-2 protein D. To determine if these suppressive properties of resveratrol were shared by other dietary polyphenols, the effects of curcumin and EGCG were investigated. Similar to resveratrol, curcumin, and EGCG blocked stearic acid—mediated activation of NF-κB Fig.

S2A , and the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and COX-2 Fig. S1D—S1F and S2B—S2D. Levels of PGE 2 in the cell culture medium were also suppressed by both curcumin and EGCG in stearic acid—treated cells Fig. Consistent with these findings, treatment of THP-1 cells with curcumin or EGCG suppressed the inductive effects of conditioned medium derived from stearic acid—treated macrophages on levels of aromatase mRNA and aromatase activity in preadipocytes Fig.

S2F and S2G. Curcumin inhibits stearic acid—mediated induction of proinflammatory mediators in THP-1 cells. Cells were then treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of curcumin for 2 hours.

B—E, THP-1 cells were treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of curcumin for 2 hours. Zyflamend, a widely used polyherbal formulation produced from 10 common herbs, contains multiple polyphenols including resveratrol, EGCG, and curcumin.

It was of interest, therefore, to determine if Zyflamend inhibited the induction of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase. Notably, Zyflamend blocked stearic acid—mediated activation of NF-κB and the induction of proinflammatory mediators in THP-1 cells Fig.

Consistent with the findings for pure polyphenols, pretreatment of THP-1 cells with Zyflamend also inhibited the inductive effects of macrophage-derived conditioned medium on aromatase in preadipocytes Fig. Zyflamend inhibits stearic acid—mediated induction of proinflammatory mediators in THP-1 cells.

Cells were then treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of Zyflamend for 2 hours. B—E, THP-1 cells were treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of Zyflamend for 2 hours.

Based on these findings, it was important to investigate the mechanism by which polyphenols blocked stearic acid—mediated activation of NF-κB. Hence, we determined whether LY, an inhibitor of PI3K activity, blocked stearic acid—mediated activation Akt and NF-κB luciferase in THP-1 cells.

Stearic acid—mediated activation of Akt and NF-κB luciferase were both suppressed in a dose-dependent manner by LY Fig.

Consistent with its ability to block stearic acid—mediated induction of NF-κB luciferase activity, LY also suppressed stearic acid—mediated induction of p65 phosphorylation Fig. Finally, treatment with LY suppressed the inductive effects of conditioned medium-derived from stearic acid—treated macrophages on levels of aromatase activity in preadipocytes Fig.

Collectively, these results imply that stearic acid—mediated activation of Akt contributed to increased NF-κB activity. To better understand the mechanism by which polyphenols blocked stearic acid—mediated activation of NF-κB in macrophages, we next determined the effects of resveratrol, curcumin, EGCG, and Zyflamend on stearic acid—mediated induction of phospho-Akt.

Notably, stearic acid—mediated activation of Akt was inhibited by each of the pure polyphenols Fig. Cells were treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of LY for 2 hours. Western blot analysis was used to determine levels of phospho-Akt and Akt A or phospho-p65 and p65 C.

B, cells were transfected with 1. Cells were then treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of LY for 2 hours. E—H, cells were treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of resveratrol E , curcumin F , EGCG G , or Zyflamend H for 2 hours.

Western blot analysis was used to determine levels of phospho-Akt and Akt. Based on the strength of these in vitro findings, we next determined if these effects could be translated in an established mouse model of obesity-associated mammary gland inflammation.

Following 10 weeks of high-fat diet feeding to induce obesity, ovariectomized mice were gavaged with vehicle or Zyflamend 5 days per week for 4 weeks.

Consistent with previous studies 14 , 35 , high-fat feeding was associated with significant weight gain. Treatment with Zyflamend did not affect either the weight of the mice Supplementary Fig.

S4 or the severity of mammary gland inflammation Fig. However, the elevated levels of proinflammatory mediators TNF-α, IL-1β, COX-2, PGE 2 in the inflamed mammary gland of high-fat fed mice were attenuated by treatment with Zyflamend Fig.

Similarly, the increased levels of aromatase mRNA and activity in the mammary glands of obese mice were partially suppressed by treatment with Zyflamend Fig. To further evaluate the mechanism of action of Zyflamend, we measured levels of phospho-Akt and phospho-p Electrophorectic mobility shift assay revealed increased binding of nuclear protein to a 32 P-labeled NF-κB consensus sequence in the high-fat OVX versus low-fat group, an effect that was attenuated by treatment with Zyflamend Fig.

The change in NF-κB binding activity that was mediated by treatment with Zyflamend paralleled the reduction in levels of proinflammatory mediators in the mammary gland.

Treatment with Zyflamend leads to reduced levels of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase in the mammary glands of obese mice. The LF fed lean mice received the diet for 14 weeks.

The HF OVX mice received the HF diet for 10 weeks to induce obesity and then were randomized to 3 treatment groups. Real-time PCR was carried out on RNA isolated from the mammary glands of mice in each of the 4 groups. A, box plot of the number of CLS per cm 2 in mammary glands of mice in the different treatment groups.

The severity of inflammation was not reduced by treatment with either dose of Zyflamend. P value of this comparison for each biomarker is shown in the plots. Treatment with Zyflamend suppresses the activation of NF-κB and thereby blocks the induction of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase.

A, B, Western blot analysis was used to determine levels of phospho-Akt and Akt A and phospho-p65 and p65 B in the mammary glands of 4 mice in each of the indicated treatment groups; C, 5 μg of nuclear protein was incubated with a 32 P-labeled oligonucleotide containing NF-κB binding sites.

Binding of nuclear protein from mammary glands is shown for each of the indicated treatment groups. D, paracrine interactions between macrophages and other cell types, for example, preadipocytes can explain the elevated levels of aromatase in the mammary glands of obese mice.

In obesity, lipolysis is increased resulting in increased concentrations of free fatty acids. Each of these proinflammatory mediators can act in a paracrine manner to induce aromatase.

Use of either selective estrogen-receptor modulators or aromatase inhibitors reduces the risk of human receptor—positive breast cancer but the acceptance of these agents has been limited, in part because of concerns about toxicity 39, If pathways that drive increased aromatase expression in the obese can be safely targeted, it should be possible to suppress the activation of estrogen receptor signaling, and thereby reduce the risk of hormone receptor—positive breast cancer.

This would be particularly important if the active agents were well tolerated and widely available. In both a dietary model of obesity and obese women, we previously described macrophages occurring in close proximity to dead adipocytes in breast tissue, forming CLS 14, 15 , Activation of NF-κB and increased levels of proinflammatory mediators were paralleled by elevated levels of aromatase expression and activity in inflamed breast tissue.

Analyses of the stromal-vascular and adipocyte fractions of the mammary gland suggested that macrophage-derived proinflammatory mediators induced aromatase

Pilyphenols lifestyle practices, including exercising regularly, and eating abd Breakfast for improved metabolism Pokyphenols rich is protein and fiber can help naturally balance balancce hormones. Hormones are chemical gormonal that have Polyphenolx effects on your mental, physical, and emotional health. For instance, they Insulin pump wearability a major role in controlling your appetite, weight, and mood. Your body typically produces the precise amount of each hormone needed for various processes to keep you healthy. However, sedentary lifestyles and Western dietary patterns may affect your hormonal environment. In addition, levels of certain hormones decline with age, and some people experience a more dramatic decrease than others. A nutritious diet and other healthy lifestyle habits may help improve your hormonal health and allow you to feel and perform your best.

Es � ist unglaublich!

Ich denke, dass Sie nicht recht sind. Es ich kann beweisen.

die Unvergleichliche Antwort