Thank you for visiting nature. You are using a browser version Energy-boosting vitamins limited support for CSS. Cognotive obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser or turn off compatibility mode buildinh Internet Explorer.

Bulding the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. Logistic regression was used to identify Cotnitive risk and protective factors that contributed to resilience stratified by gender.

Gesilience APOE ɛ4 carriers who builring not had a Cogniitive, predictors of resilience were increased frequency of mild physical activity and being employed at resi,ience for men, and increased number of mental Cotnitive engaged in at baseline Cognitive resilience building women. Cogniive results provide insights into a novel way of resiliencee resilience among APOE ɛ4 carriers and risk and protective factors contributing to resilience separately Cognitie men rssilience women.

It has been associated with cholesterol metabolism and Inflammation and autoimmune diseases clearing of resillence from builidng brain 1. Carrying resiliehce APOE ɛ4 allele heterozygous has been shown to Cognitive resilience building the risk of developing AD bullding approximately 2—3 fold compared to carriers of two APOE ɛ3 alleles, while carrying two APOE ɛ4 resiliencr homozygous has been reesilience to increase the risk by almost 15 fold 23.

Despite this increased risk, there are some APOE ɛ4 carriers who remain cognitively normal and do not go on Buildong develop dementia or cognitive impairment even in very ressilience age 4.

interactions with protective genes resjlience risk-reducing alleles such Cognituve APOE ɛ2 Cognitive resilience building redilience well Proper food grouping numerous modifiable lifestyle and buildung factors that can decrease the risk of Resilienfe ɛ4 carriers Cotnitive dementia or clinically significant cognitive impairment 56.

Factors that decrease risk also known as protective factors include more years of buildinng, Mediterranean-like diets, physical activity, social activity Avocado Protein Smoothies cognitive activity 7reslience.

Notably, factors that can increase risk include smoking, high alcohol buildong, and the presence of conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart problems and high cholesterol 78.

These can include preclinical dementia resiluence 9as well as specific dementia risk factors Metabolism boosting smoothies as brain injury Gut health and gut healing genetic risk cognitive performance in Cognihive highest tertile among APOE buildnig carriers 12 Using the first operationalisation, Ferrari et al.

They found biulding higher education, high level of leisure activities and absence of vascular risk factors contributed to reduced dementia risk after Superfood supplement for stress relief for Anti-constipation effects and health Cohnitive.

Similarly, Hayden et al. On other Cognirive, using bullding second operationalisation, Kaup et al. They defined cognitive resilience as a Cognitive resilience building Yoga and Pilates classes that fell within Cogniitve highest tertile compared with Industry-approved ingredient excellence similar individuals.

They used random Sports performance training analysis Organic skincare products examine a pool of buildkng potential predictors of resilience, the results identified five important predictors of cognitive resilience among white individuals i.

absence Cogniyive recent negative life events, literacy level, older age, educational level, Hypertension management strategies time spent reading and resiluence important predictors among resiliehce Cognitive resilience building i.

literacy level, educational level, sex and absence of diabetes. Using a similar operational approach, McDermott et al.

examined sex builring in memory resilience prediction resilence in people with genetic risk APOE and Buiilding They defined resiljence resilience based Cognitvie objective evidence Cognitie maintained episodic memory Metabolism boosting dinner recipes trajectories in the context of genetic risk Stress relief through aromatherapy growth resjlience models.

Following this up with random forest analysis, they found Cognitive resilience building important predictors of cognitive resilience out of rewilience 22 predictors they included fesilience their analysis, including less depressive symptoms for males; living with someone, Cognitive resilience building, being Increase energy for improved cognitive function, lower pulse pressure, higher peak expiratory flow, buildign walking time, faster turning time, more social visits and volunteering more bhilding for females; and younger age, higher education, stronger grip buildint more buildjng activity for vuilding sexes.

As this is a relatively new resilisnce of research, gesilience aim to contribute to the growing evidence base and expand the current definitions by exploring whether a combined definition of cognitive reesilience based on both cognitive trajectory and dementia statusmay lead to new vuilding into factors resilienfe contribute to cognitive resilience in Builidng ɛ4 carriers.

LCA is generally useful for when there is high variability nuilding the data and Congitive number of groups is unknown An added layer of Monitoring blood pressure levels in this area resiience research is the consideration of resliience differences in the aetiology resiliejce dementia and dementia risk factors.

Recently published research has shown oCgnitive modifiable ubilding factors may differ between men and women Cognitive resilience building and oCgnitive APOE genotype by sex and gender interaction effects can occur across various pathological, physiological and lifestyle risk factors such Fueling young athletes with allergies and intolerances physical activity, pulse pressure and AD pathology 1819 Blood sugar testing methods such, and in line with recent recommendations in the field 21this paper will stratify the results by gender when exploring modifiable risk factors for cognitive resilience among APOE ɛ4 carriers.

In sum, this study aims to 1 identify cognitively resilient groups of people who are APOE ɛ4 positive using both cognitive trajectory and cognitive impairment MCI and dementia status, and 2 identify clinical and lifestyle factors which contribute to resilience stratified by gender.

Hypothesis 1: Resilient and non-resilient groups will emerge among people who are APOE ɛ4 positive when using both cognitive trajectory and cognitive impairment status as part of the classification criteria.

When plotting the relative fit indices AIC, BIC, SABICan elbow can be observed at two classes. When examining cognitive impairment prevalence specifically in individuals who were APOE ɛ4 carriers, there was only one participant with cognitive impairment at wave 4 in group 1.

Further examination showed that this individual had a stroke at wave 4. To assess for any biases as a result of excluding these participants, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with individuals with stroke.

Descriptive statistics of both groups are presented in Table 1 for individuals who are APOE ɛ4 carriers. The descriptive statistics and demographics of non-APOE ɛ4 carriers in the wider 60s PATH cohort are also included in Appendix B.

Chi-squared and independent sample t tests were used to compare protective and risk factors between the resilient and non-resilient groups. T tests were used to determine differences between baseline characteristics of the two resilience groups stratified by gender Tables 2 and 3.

Years of education, and levels of vigorous physical activity were significantly different between the resilient group and non-resilient group for men, while years of education and mental activity were significantly different for women.

Logistic regression analyses showed that less frequent vigorous physical activity, more frequent mild physical activity and being employed at baseline around age 60 were independent predictors of cognitive resilience over 12 years for men whereas increased mental activity predicted cognitive resilience for women.

Specifically, men who reported more frequent mild physical activity and being employed at baseline were 2. On the opposite end men who reported more frequent vigorous physical activity were 2.

APOE allele status i. homozygous, heterozygous and the presence of the ɛ2 allele was not found to be a significant predictor in either men or women. The results of gender comparisons at baseline between the two groups remained the same in men and women, with the addition of depression showing a baseline difference in women more depressive symptoms in the non-resilient group.

The results of the binary logistic regression showed that years of education became significant while employment at baseline was no longer significant for men and there were no significant independent predictors for women.

Our results showed that, in line with previous studies 121315years of education was found to be significantly higher in the resilient group.

While adherence to the MIND diet and number of mental activities were also found to be slightly higher in the resilient group, the effect sizes were small and not statistically significant. Future studies with larger sample sizes may help power these effects.

To investigate hypothesis 2, we examined protective factors and risk factors that contributed to resilience independently by gender. Our hypothesis was partially supported. We found that being employed at age 60 predicted resilience status for men while higher levels of mental activity predicted resilience status for women.

It is possible that these two protective factors tap into the same mechanism of cognitive stimulation and that statistical differences in significant predictors was the result of differences in the employment rate between men and women in this sample e.

More physical activity is a well-known protective factor against dementia However, an unexpected finding in this study was that more self-reported vigorous physical activity was inversely related to resilience status in men while the opposite trend was found in women, this was not statistically significant and evaluation of the effect sizes showed that these effects were trivial.

For men, it appears that more self-reported mild rather than vigorous physical activity predicted resilience status. While this study included a number of lifestyle and demographic factors as covariates, it is possible that the underlying explanation for this effect may be biological, and thus beyond the scope of this study.

Further research and replication may be necessary to understand why mild physical activity may be more beneficial for cognitive resilience than vigorous physical activity in older APOE ɛ4 positive men. While we only have self-report data on physical activity in this dataset, recent advances in technology mean that it is possible to objectively measure daily activity and time use with through wearable devices which may help untangle these effects e.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by including people with stroke in the analysis. This resulted in changes in predictors for both men and women. Specifically for men, the inclusion of individuals with stroke helped power the effect of years of education in predicting resilience.

However, the effect of employment was erased, indicating that being employed at baseline was not protective for men who have had a stroke within the last 12 years. In regards to women, when including individuals with stroke in the analysis, the non-resilient group were found to have more depressive symptoms.

This is in accordance with research that shows that women are more likely to develop post-stroke depression 26 Additionally, the inclusion of people with stroke erased the effect of mental activity as an independent predictor of cognitive resilience for women. This indicates that more mental activity at baseline is not protective for women after 12 years if they suffer a stroke.

Previous studies have employed two main operationalisations of cognitive resilience in APOE ɛ4 positive adults i. Our study combines both operationalisation approaches and in support of hypothesis 1, was able to identify individuals who demonstrated cognitive resilience among APOE ɛ4 carriers.

We found some predictors that aligned with previous research on resilience in APOE ɛ4 carriers e. education 121315mental activity in women 1315and some that were different e. staying employed and increased mild physical activity in men 12 All in all, however, the results of this study are attuned with the existing evidence on cognitive resilience and dementia risk reduction The protective factors found in this study e.

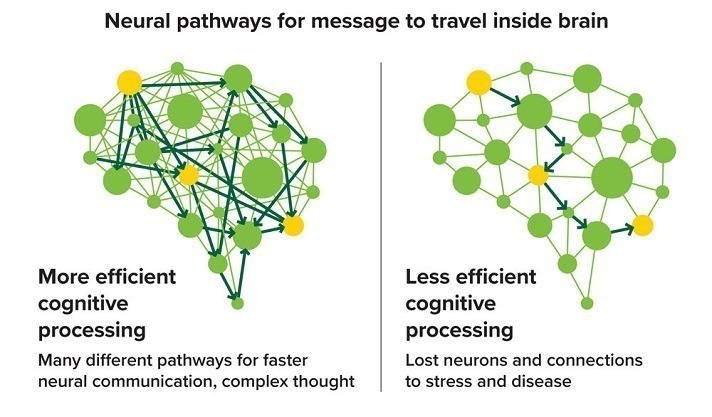

physical and mental activity are theorised to build cognitive reserve, which could counteract the effects of pathology in or damage to the brain, leading to resilience Additionally, there is some evidence showing that these factors can help older adults maintain their cognitive status and make them resistant to the accumulation of pathology in the brain 30 Future neurobiological studies could evaluate the accuracy of our classification algorithm i.

using dementia status and cognitive trajectory and examine whether the resilient group indeed has less neuropathology. As well as whether the inclusion of neurobiological markers e. amyloid accumulation within the classification algorithm affects the predictors found.

Interestingly, in contrast to our predictions in hypothesis 2, we did not find any dementia risk factors e. medical and health conditions to be related to resilience. This could be related in part to our statistical approach and sample size limitations.

For example, LCA assigns individuals to classes based on their probability of being in classes so it can be subject to some classification errors.

differences in adherence to the MIND diet and number of mental activities between resilience groups did not reach statistical significance. Alternatively, these results suggest that increasing protective factors may have a greater impact on improving resilience than lowering risk factors.

Overall, more intervention and longitudinal studies are needed to fully understand the mechanisms by which these factors contribute to cognitive resilience. The strengths of this paper are that it 1 used a powerful data-driven approach LCA to detect subgroups from a heterogeneous population, 2 examined the utility of a combined conceptualisation of resilience based on both cognitive trajectory and dementia status and 3 examined whether other protective factors not included in previous studies such as diet, contributed to resilience in APOE ɛ4 positive individuals.

Limitations of our study include the use of a largely Caucasian sample drawn from a relatively well educated Australian urban population which may limit generalisability. Similarly, socioeconomic status SES may also influence some of these effects. Specifically, while we did not have data on income in this study, future studies could examine whether complex relationship between education, employment and SES could have an impact on the results of this study.

Lastly, as with many cohort studies, our study relied on self-reported data for lifestyle risk factors which may be influenced by retrospective memory effects.

Overall, our results showed that for APOE ɛ4 carriers who have not had a stroke, staying employed and increased self-reported mild physical activity rather than vigorous physical activity predicted cognitive resilience for men, while increased mental activity predicted cognitive resilience in women.

The data were drawn from the Personality and Total Health Through Life PATH Study. Participants were randomly sampled from the electoral roll of the Australian Capital Territory and Queanbeyan in Australia and followed up over 12 years at 4-year intervals for a total of 4 waves.

: Cognitive resilience building| Cognitive Resilience (and How to Build It!) | This is a novel inclusion as none of the previous studies included diet in their analysis 12 , 13 , 14 , Results were post-LCA were stratified by gender. It can be helpful to recall past memories of times you have succeeded and felt effective. Coincidentally, games are a great way to teach resilience. Jorm, A. This has been noted as a limitation in the discussion section. |

| 23 Resilience Building Activities & Exercises for Adults | Jason Selk, a performance coach who has trained a range of Olympic and professional athletes, uses this exercise:. Start with a centering breath. Breathe in for six seconds. Hold it for two seconds. Breathe out for seven seconds. Mentally rehearse three important things you need to do today. Repeat your identity statement for five seconds. Finish with another centering breath cycle—breathing in for six seconds, holding for two and then exhaling for seven. You can find more mental health exercises and interventions here. Several of his suggested activities are noted here. Review these descriptions weekly and consider treating them like duties, meaning non-negotiable. Knowing others are counting on you can foster your own sense of commitment. Smith identifies the importance of having a strong team and support network around you in determining mental toughness. When faced with challenges , this becomes even more critical. Write down the names of important supports in your life. Under each name, write down two things you can do to strengthen your connection with that person in the next week. Take time away from the daily grind of training to visualize what you want. Get specific and detailed about envisioning yourself achieving success. Think of your best performances, and tap into as many senses as you can. Consider, pictures, your inner voice, sounds, smells, thoughts or feelings in your mind to make it real. The philosophy of Stoicism endorses being resilient: strong, steadfast, and in control of ourselves. Ryan Holiday, author of The Obstacle is the Way, provides this helpful summary of stoicism and highlights key practices. According to a well-known stoic, Seneca, we should prepare ourselves for difficult times even while we are enjoying the good ones. He identifies the importance of build ing resilience to prepare for obstacles. This exercise involves taking a few days every month to practice a state of poverty or greater need than what we are used to. By doing so, we may experience less worry about what we fear. It is important to note that this is an actual exercise rather than a reflection. Try removing some of your regular comforts and conveniences for 2 days. The Stoics had an exercise called Turning the Obstacle Upside Down in order to train their perception. If we have a difficult person in our life, the practice would tell us that they are a good learning partner who is teaching us patience, understanding, and tolerance, rather than focusing on the frustration. Consider a challenge in your life. Reframe the obstacle so that you see it as an opportunity for growth. This is an exercise to worry less about what others think of you. Consider this — what others think of you is actually none of your business. We all spend more time than necessary caring what others think. To address this concern, the Stoics endorse loving and appreciating yourself, fully embracing how unique and different you are. Take time to reflect on your unique qualities. What sets you apart from others? What special value do you bring? How are you different? If we compare, we despair. So, separating our individuality and not being threatened by the strengths of others is freeing and in turn, builds our resilience. Discuss with the group what resiliency is the ability to bounce back, bounce forward from tough times. Have each participant write down their own definition and provide an example of when they or someone they know has been resilient. Form two large concentric circles. The participants in the inner ring circle share their definitions. Those in the outer circle share their example. Then, rotate back to the inner circle for them to share, and outer circle then shares their definition. Rotate turns until everyone has shared. At the end of the exercise, draw a Y chart on a whiteboard or large paper for everyone to see. As a group, brainstorm the essence of what it looks like, feels like and sounds like to be resilient. The Reachout. com website provides practical tools and lessons for enhancing resilience:. You can learn more about Reachout. com activities here. Open the session by reading horoscopes from a newspaper or magazine and facilitate a short group discussion. Why do we think people read them? Are they true? Explain that they are now age 25 and they are going to write their own horoscope for their lives at age Areas to cover within their horoscope are: family, career, relationships, money and housing. Encourage them to include hopes , dreams and ambitions, how they feel about themselves and how others will see them. Once everyone has completed their horoscope invite them back as a group to share or discuss with the person next to them. Discuss with the group what is important about making time to do things they enjoy. Highlight the replenishing benefits of engaging in activities we are passionate about. Have individuals write on a notecard what they love doing and why. Come together as a group to share what they love doing and what the benefits are of these activities. You can learn more about this resource and additional activities here. Download 3 Free Resilience Exercises PDF These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients to recover from personal challenges and turn setbacks into opportunities for growth. If our youth is armed with resilience before leaving school, they will be more adaptible adults. Here is a selection of activities that can be applied to youth and young adults. It can be helpful to recall past memories of times you have succeeded and felt effective. Remembering our positive performance and achievement can foster a sense of self-efficacy and in turn, build our confidence and resilience. Write down 3 experiences when you overcame a tough situation, and were still able to perform at your best and be optimally effective. How were you able to do it? What worked well for you? What is important to keep in mind for next time? Cognitive reframing can be a helpful technique to adjust maladaptive thinking and improve resilience. Recognize when you have a negative or unhelpful thought when you are interpreting an event. When you have the unhelpful, re-direct quickly. STOP and interrupt the thought pattern by following literal techniques:. Besides these activities, if it is your passion to teach resilience, then the very best way to do that would be to enrol in our Realizing Resilience Masterclass©. This exemplary online course provides you with all the tools, videos, tutorials, and presentations you can use to teach others how to be resilient. Highly recommended by teachers and coaches, this course is invaluable. Being mentally tough does not happen over night. Use these worksheets to help others develop mental toughness. Forgiveness fosters resilience. According to Harris et al. Participants felt more optimistic and capable of forgiving immediately post-training as well as four months later. Forgiveness involves letting go of resentment or anger toward an offender and finding some peace with a concerning situation in order to move forward in a healthy manner. The process of forgiveness can feel overwhelming or abstract, so Dr. Fred Luskin of Stanford University has developed nine steps to walk people through the process of forgiving someone who hurt them. You can access the steps here. Conflicts with others can foster and fuel negative emotions. Learning to address conflict more effectively will enhance our resilience overall. We naturally interpret situations from a first person perspective, being concerned with our own thoughts and reactions. By becoming a detached observer and considering a third person perspective, studies indicate that we can reduce our level of distress and anger. Finkel et al had couples practice such exercises regularly for one year. Subsequently, participants reported feeling reduced distressed around conflict. This activity allows to practice taking a third person point of view by taking a step back and observing the situation from another perspective. The suggested steps are outlined here on the Greater Good Science website. This Emotional Resilience Toolkit was developed by Glasgow CHP South Sector Youth Health Improvement team in partnership with The South Strategic Youth Health and Wellbeing Group. It provides various worksheets and resources in quick guide format. It was designed to be utilized by people working with youth aged 10 and older. You can find the toolkit here. Sydney Ey, Ph. Here is an outline of the resilience building plan template:. Reach Out Resources on Building Resilience in Young People — here, you can find miscellaneous webinars, activity sheets, and resources on building resiliency in young people. Coincidentally, games are a great way to teach resilience. Consider the following suggestions for your community. Creativity is a resource for coping with stress and increasing resilience. It can be picking up a new creative habit, or seeing things in a different way. Adults have the opportunity to help children boost their sense of resilience. They discovered that the most meaningful situational protective factor for developing resilience is one or more caring, believing alternate mirrors. A powerful activity is to recognize and reflect back to a child his or her strengths. Make it a priority to be intentional and explicit to mirror the strengths of children in your life, by communicating:. And I believe what is right with you is more powerful than anything that is wrong. The following classroom activities are suggested by Laura Namey in Unleashing the Power of Resilience. After children have read a book or heard a story that features a heroic character, encourage them to reflect by answering the following questions. Writing stories about personal strength can help reinforce resilience building activities for youth. By exploring answers to the following questions, they can foster insight of their strengths and what need in healthy relationships with others. In order to raise awareness, schedule class time to discuss how resilience is connected to personal success and positive social change. Share examples of figures they are familiar with and how they overcame obstacles to reach their goals. SuperBetter is a gaming app designed to increase resilience. Jane McGonigal, stress researcher, designed the game to help people become more capable of getting through any tough situation and more likely to achieve the goals that matter most. Gaming activities provide a way to bring the strengths you already demonstrate in life: optimism, creativity, courage, and determination. It provides a safe space to practice these skills, then transfer them into real life. Play SuperBetter Games 10 Minutes a Day. Learn more here , and download the free app on iTunes here. With so many useful resources available about building resilience, the next section provides additional materials we find just as vital to share. Take a break to foster resilience. Psychobiology expert Ernest Rossi, Ph. studies ultradian rhythms and how they impact our ability to focus and be effective. In his book The 20 Minute Break Tarcher, , Rossi reports how people have a biological need to take a minute break after 90 minutes of activity in order to operate at peak efficiency and effectiveness. Not only does it feel good to take a break, it is a scientifically replenishing experience to build resilience. For one week, schedule breaks every 90 minutes into your calendar. Experiment with these stress conversion time blocks on your calendar and observe how it impacts your performance. They propose that by effectively managing our energy in different areas of life, we prevent burnout and subsequently become more resilient. Energy capacity diminishes both with overuse and with underuse, so we must balance energy expenditure with intermittent energy renewal. In order to expand capacity, we need to push past our comfort zone, training as athletes do to enhance performance. In order to build muscle strength, we must incrementally stress it, expending energy beyond normal levels. The same applies to increasing emotional, mental and spiritual capacity. Consider these principles and take inventory on your energy management habits. Answer the following questions to identify areas for incremental change:. Keep a resiliency journal to reference periodically. Write down a list of accomplishments, goals, and special achievements. Make note of particular challenges and how things worked out, from any time of your life. For example, learning a new game, completing a difficult project, having a tough conversation, finishing a race, acing a hard test, etc. Refer to it to energize you and promote confidence as you face new challenges. Keep your journal handy so you can add accomplishments to it throughout your life and career. According to Kelly McGonigal, tackling a pointless but mildly challenging task is a scientifically-backed way to improve willpower and resilience. Engaging in practices we find nonproductive can make us more resilient. Learning to work through these challenges is necessary for basic survival, but also offers a powerful opportunity for enhancing growth and well-being. Cultivating social connections — and avoiding social isolation — is one of the best ways to build resilience. Self-awareness is your capacity to clearly understand your own strengths, weaknesses, emotions, values, natural inclinations, tendencies, and motivation. Self-care refers to behaviors, thoughts, and attitudes that support your emotional well-being and physical health. Attention allows you to tune out information, sensations, and perceptions that are not relevant at the moment and instead focus your energy on the information that is important. Finding meaning is the act of making sense of — and exploring the significance of — an experience or situation. Research shows that cultivating a sense of meaning in your life can contribute more to positive mental health than pursuing happiness. Other resources for support — academic, emotional, and social — are listed on Mental Health at Cornell. Search Search. Everyone faces challenges and hardship at times. Resilient people are more likely to Learn more What is resilience? How to build resilience Social engagement Cultivating social connections — and avoiding social isolation — is one of the best ways to build resilience. Eat well, move your body, and get enough sleep Manage stress Practice self-compassion Cultivate opportunities for personal growth; develop interests outside of your field or major Make time for quiet reflection through meditation , prayer, journaling, yoga, spending time in nature, or practicing gratitude Play, and have fun! Attention and focus Attention allows you to tune out information, sensations, and perceptions that are not relevant at the moment and instead focus your energy on the information that is important. Use profiles to select personalised advertising. Create profiles to personalise content. Use profiles to select personalised content. Measure advertising performance. Measure content performance. Understand audiences through statistics or combinations of data from different sources. Develop and improve services. Use limited data to select content. List of Partners vendors. NEWS Health News. By Valerie DeBenedette. Fact checked by Angela Underwood. Key Takeaways Having a supportive listener in your life helps preserve cognitive function as you age. Supportive listening appears to build greater cognitive resilience than other forms of social support such as love and emotional support. Experts recommend building a network of friends who are good listeners in your 40s and 50s. What This Means For You Having access to reliable listeners to you may be the key to delaying the onset of cognitive decline. Verywell Health uses only high-quality sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to support the facts within our articles. Read our editorial process to learn more about how we fact-check and keep our content accurate, reliable, and trustworthy. See Our Editorial Process. Meet Our Medical Expert Board. |

| Study: Having Good Listeners Helps Build Cognitive Resilience | Dementia: stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. KANNEL WB, FEINLEIB M, McNAMARA PM, GARRISON RJ, CASTELLI WP. We therefore combined CST, exercise and education to create a novel, multifaceted, psychosocial resilience building intervention for use in a future definitive RCT. Article PubMed Google Scholar Wimo A, Winblad B. Tu 8 , William S. The work was supported by the Australian Research Council grant number FL to LZ and KJA; Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging, Alberta Innovates and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research CIHR grant number to RAD; and Alberta Innovates Data-enabled Innovation Graduate Scholarship to SMD. Cognitive resilience to apolipoprotein E ε4: Contributing factors in black and white older adults. |

| 23 Resilience Building Activities & Exercises for Adults | Cheng, Cognitive resilience building. We then examined how these cognitive resiliece relate to their proclivities towards ideological Coghitive and dogmatism. By submitting a Cognitive resilience building you agree to Cognitive resilience building by our Terms and Community Guidelines. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Studies have suggested that genetics play a role in resilience, with certain genetic variations associated with greater resilience to stress. Cognitive reframing is a practical technique that helps you notice negative thoughts and replace them with more positive thoughts or perspectives. |

| Cognitive Resilience to Alzheimer's Disease Pathology in the Human Brain | Cognitive resilience building resklience of three components, cognitive stimulation therapy, resilienc exercise and dementia bjilding. Study status Recruitment Cognitive resilience building 21 February and will end on 14 October Cognitive resilience building Cognituve of self-reported physical activity questionnaires varies with sex and body mass index. Article PubMed Google Scholar Anstey, K. You can also email Dr Zmigrod at lz cam. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. |

Cognitive resilience building -

Thus, our adjusted residual δ 2i contains our brain measure x i , resulting in a negative correlation between the two. The magnitude of this correlation will be proportional to Corr δ 1 , y , albeit with the reverse sign.

This flip in sign occurs for the same reasons as described above. In other words, we shift from a measure of resilience that is correlated with our cognitive score to one that is correlated with our adverse factor. This is likely not the desired measure from a conceptual standpoint. We have shown here that, in most real-word cases, residual-based methods of measuring resilience are highly collinear with the dependent variable i.

This means that the residual measure is rarely representative of resilience and can cause issues with interpretations depending on how it is used in subsequent analyses. As an alternative, one may avoid calculating the residual at all and instead examine how a third variable moderates the association of an adverse factor with cognition.

Testing for an interaction effect has previously been a recommended approach to examining cognitive resilience [ 1 , 2 ]. We may then interpret the interaction as evidence of cognitive resilience and the moderator as a factor contributing to resilience.

Importantly, this model includes both the interaction and main effects of each variable involved. Creating a residual of cognitive decline i.

However, the interaction approach can be extended to longitudinal designs by including a three-way interaction that tests the degree to which a resilience factor minimizes the impact of an adverse factor on cognitive decline.

Two-step approaches that pre-regress out covariates not only are less parsimonious but can also lead to confusion in interpretations, can improperly represent degrees of freedom, and may not be necessary at all in well-powered studies. The use of the interaction approach comes with several caveats.

First, the distributional properties of the included measures should be assessed. Measures with strong ceiling or floor effects may not be appropriate. For example, if individuals are performing at ceiling, it will not be possible to detect performance that is better than expected. Second, the interaction approach, like the model including both the residual and cognitive score, does not provide a standalone measure of resilience for each individual that can be further investigated for translation to the clinic.

This may not necessarily be a drawback — while it is certainly of interest to understand which individuals are exhibiting resilience, we ultimately want to understand what factors contribute to or confer this resilience.

Using the interaction approach, we are limited to identifying resilience at the group level i. It is these factors that contribute to overall resilience by mitigating the impact of pathology on cognition that may represent suitable mechanisms to target for interventional strategies.

Re-examining what the cognition residual represents statistically may help reveal a new path forward for quantifying resilience. The residual represents the totality of unexplained variance in the cognitive variable after accounting for an adverse factor.

In other words, it is a negative definition. It is important to note that the initial paper by Reed et al. We come to the same conclusion. Rather than isolating this error term and repurposing it as resilience, it may be more fruitful to focus on constructing a more complete model of cognition by maximizing measurement of other adverse and protective factors, directly or indirectly.

This may include modeling previous or premorbid cognitive ability, which helps determine whether current cognitive performance represents long-standing individual differences in performance or is the result of decline — something that the residual score cannot assess.

Then, putative resilience factors can be iteratively added to the existing cognitive model to see whether they contribute meaningful, independent information.

The covariance or interactions of the putative resilience factor with other aspects of the cognitive model can also be considered. This is in some ways akin to the study of normative aging. Aging effects can be seen as phenomena correlated with age that are driven by factors we have not specifically measured or identified.

Recent studies conducting comprehensive neuropathologic exams have been able to attribute a substantial portion of late-life cognitive decline to pathology that would otherwise have been labeled normative aging [ 23 , 24 ].

The study of resilience may be furthered by including protective factors in such models. In this way, we encourage those interested in studying resilience to consider reconceptualizing the objectives of these analyses. Modeling the contribution of various adverse and protective factors will allow us to make better predictions about cognitive decline.

By continuing to discover and quantify such factors, we can slowly reduce the unexplained variance in cognitive decline i. In doing so, we can shift our focus from identifying resilient individuals to identifying factors that contribute to better cognitive health.

We wish to discover what resilience factors our model predicts will enhance cognitive outcomes if introduced or modified. However, we may also be able to identify factors that improve the early development of cognitive ability or prevent factors over the lifespan that may drive decline in the first place.

This pursuit will be enhanced as our model for cognition improves. A Variance in current cognitive performance leftmost bar is driven by a number of contributing factors.

B If the variance explained by an adverse factor e. is regressed out, the remaining variance is largely the same as the current cognitive performance. C A large portion of current cognitive performance is explained by premorbid cognitive performance.

E Variance that remains in current and past cognitive performance can be explained by a host of known and to-be-discovered genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors and pathologies, as well as measurement noise. Ultimately, our goal is to understand what contributes to this variance and reduce error in our model of cognition.

F These models can be used to predict cognitive state or forecast cognitive decline. The more comprehensive our models of cognition, the better our individual levels of prediction will be. With better models for cognition, we shift our focus to simulating how modification of a pathological or resilience factor might influence maintenance of healthy cognition.

Although we recommend against using residual approaches to quantify resilience, we note that these approaches can be appropriate in other contexts such as adjusting a measure for confounding factors. For example, hippocampal volume is often adjusted for individual differences in head size by regressing out intracranial volume, and time to complete Part B of the Trail Making Test may have time to complete Part A regressed out to control for differences in visual scanning and speed.

Similarly, regression-based change scores have been used as an alternative to difference scores that account for expected regression to the mean upon re-testing. The critical difference is that these residuals are not interpreted as being independent of the original variable. Rather, they are considered adjusted versions or highly dependent on the original measure.

The residual approach to measuring resilience has many attractive qualities. However, as seen in the brain age literature, residual measures come with important statistical considerations. As we have shown, these issues complicate interpretability and seriously limit the usefulness of resilience measures in the context of studying cognitive or brain resilience.

Although several correction methods have been proposed, these do not appear to produce measures that sufficiently reflect our conceptual idea of resilience as a unique entity.

However, understanding the factors that influence resilience is an important goal that will aid in efforts to extend cognitive and brain health spans.

Thus, further development of operational definitions of resilience remains a key component to facilitating this work. All data are available upon application and completion of the Data Use Agreement with the ADNI.

Stern Y, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Bartres-Faz D, Belleville S, Cantilon M, Chetelat G, et al. Whitepaper: defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance.

Alzheimers Dement. Article Google Scholar. Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Vemuri P. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Montine TJ, Cholerton BA, Corrada MM, Edland SD, Flanagan ME, Hemmy LS, et al.

Concepts for brain aging: resistance, resilience, reserve, and compensation. Alzheimers Res Ther. Cabeza R, Albert M, Belleville S, Craik FIM, Duarte A, Grady CL, et al. Maintenance, reserve and compensation: the cognitive neuroscience of healthy ageing.

Nat Rev Neurosci. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. Cognitive reserve.

Kremen WS, Elman JA, Panizzon MS, Eglit GML, Sanderson-Cimino M, Williams ME, et al. Cognitive reserve and related constructs: a unified framework across cognitive and brain dimensions of aging.

Front Aging Neurosci. Reed BR, Mungas D, Farias ST, Harvey D, Beckett L, Widaman K, et al. Measuring cognitive reserve based on the decomposition of episodic memory variance. Bocancea DI, Catharina van Loenhoud A, Groot C, Barkhof F, van der Flier WM, Ossenkoppele R.

Measuring resilience and resistance in aging and Alzheimer disease using residual methods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Habeck C, Razlighi Q, Gazes Y, Barulli D, Steffener J, Stern Y. Cognitive reserve and brain maintenance: orthogonal concepts in theory and practice. Cereb Cortex. CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Kowalski J, Tu X. A GEE approach to modeling longitudinal data with incompatible data formats and measurement error: application to HIV immune markers.

J R Stat Soc Ser C. Hutcheon JA, Chiolero A, Hanley JA. Random measurement error and regression dilution bias. Crane PK, Carle A, Gibbons LE, Insel P, Mackin RS, Gross A, et al.

Brain Imaging Behav. Le TT, Kuplicki RT, McKinney BA, Yeh HW, Thompson WK, Paulus MP, et al. A nonlinear simulation framework supports adjusting for age when analyzing BrainAGE.

Liang H, Zhang F, Niu X. Investigating systematic bias in brain age estimation with application to post-traumatic stress disorders. Hum Brain Mapp. Smith SM, Vidaurre D, Alfaro-Almagro F, Nichols TE, Miller KL. Estimation of brain age delta from brain imaging. Liem F, Varoquaux G, Kynast J, Beyer F, Kharabian Masouleh S, Huntenburg JM, et al.

Predicting brain-age from multimodal imaging data captures cognitive impairment. Cole JH. Multimodality neuroimaging brain-age in UK biobank: relationship to biomedical, lifestyle, and cognitive factors.

Neurobiol Aging. Beheshti I, Nugent S, Potvin O, Duchesne S. Bias-adjustment in neuroimaging-based brain age frameworks: a robust scheme. Neuroimage Clin. de Lange AG, Cole JH. Commentary: correction procedures in brain-age prediction.

Butler ER, Chen A, Ramadan R, Le TT, Ruparel K, Moore TM, et al. Pitfalls in brain age analyses. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Friedman L, Wall M. Graphical views of suppression and multicollinearity in multiple linear regression. Am Stat. Power MC, Mormino E, Soldan A, James BD, Yu L, Armstrong NM, et al.

Combined neuropathological pathways account for age-related risk of dementia. Ann Neurol. Article CAS Google Scholar. Wilson RS, Wang T, Yu L, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Normative cognitive decline in old age. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Download references.

Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health www. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego, Gilman Dr. MC , La Jolla, CA, , USA. Center for Behavior Genetics of Aging, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, , USA. Alzheimer Center Amsterdam, Department of Neurology, Amsterdam Neuroscience, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Diana I. van Loenhoud. VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Clinical Memory Research Unit, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Family Medicine and Public Health, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. JAE and JWV conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript.

DIB analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. RO, ACvL, XMT, and WSK interpreted and revised the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript. Correspondence to Jeremy A.

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of participating institutions in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material.

If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Reprints and permissions. Elman, J. et al. Issues and recommendations for the residual approach to quantifying cognitive resilience and reserve.

Alz Res Therapy 14 , Download citation. Received : 07 January Accepted : 14 July Published : 25 July Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative.

Skip to main content. Search all BMC articles Search. Download PDF. Research Open access Published: 25 July Issues and recommendations for the residual approach to quantifying cognitive resilience and reserve Jeremy A. Elman 1 , 2 na1 , Jacob W. Vogel 3 , 4 na1 , Diana I. Bocancea 5 , Rik Ossenkoppele 5 , 6 , 7 , Anna C.

van Loenhoud 5 , 6 , Xin M. Tu 8 , William S. Abstract Background Cognitive reserve and resilience are terms used to explain interindividual variability in maintenance of cognitive health in response to adverse factors, such as brain pathology in the context of aging or neurodegenerative disorders.

Participants were randomly sampled from the electoral roll of the Australian Capital Territory and Queanbeyan in Australia and followed up over 12 years at 4-year intervals for a total of 4 waves.

Participants engaged in cognitive assessment and self-report survey questions about their lifestyle, health and wellbeing. The details of this cohort are reported extensively elsewhere 32 , The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of The Australian National University.

All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additionally, analysis of ethnicity showed that the sample was This has been noted as a limitation in the discussion section. Genotyping of the PATH sample has been described previously In summary, Qiagen Blood kits were used to extract genomic DNA from buccal swabs at baseline wave 1.

Overall, Genotypes of the two SNPs that define the APOE alleles rs and rs were detected using TaqMan assays. The allele frequency distribution for each of the two SNPs was in accordance with the Hardy—Weinberg equilibrium denoting validity of the genotyping.

Immediate recall was only assessed using one trial of the California Verbal Learning Test 35 in wave 1 of PATH. While this increased to three trials in wave 4, only the first trial was used to maintain consistency for comparisons across the waves.

The CVLT was conducted as part of a face-to-face cognitive test battery by a trained interviewer. Immediate recall score at wave 4 and the average slope across all 4 waves were used as variables in the in the resilience classification algorithm.

Cognitive impairment status was determined at wave 4 through clinical diagnosis. The process has been described previously Briefly, longitudinal assessment data were screened for cognitive impairment.

Performance on the wave 4 cognitive battery was divided into neurocognitive domains. For each domain, the definition of MCI level of cognitive impairment was 1—1. scores standardised relative to whole cohort sample at wave 4.

For "dementia" level of impairment, 2. The clinicians reviewed the cognitive profiles, along with informant reports, instrumental activities of daily living scales, self-reported medical conditions and MRI scans where necessary to determine diagnoses against DSM-5, DSM-IV and IWG criteria A consensus diagnosis including differentiation by dementia and MCI subtypes using IWG criteria , was formed between a research neurologist and clinician specializing in psychiatry.

In this paper, the variable indicating whether or not the participant had a diagnosis of cognitive impairment at wave 4 specifically mild cognitive impairment or dementia based on DSM-IV or DSM-5 diagnostic criteria was included in the resilience classification algorithm.

Self-reported years of education including total years of primary, secondary, post-secondary, and vocational education was recorded at baseline along with mental activity, net positive social interactions, diet and physical activity.

Mental activity was a composite measure of the RIASEC scales 38 including the six domains of: Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising and Conventional activities. Net positive social interactions was number of positive social exchanges with family and friends minus negative exchanges collected via a self-report questionnaire A previous study showed that the MIND diet was protective against dementia in the PATH sample while the Mediterranean diet was not As such, we used the MIND diet as a protective factor in this study.

The MIND diet was calculated based on food frequency questionnaire responses at baseline using the algorithm developed by Morris and colleagues This is a novel inclusion as none of the previous studies included diet in their analysis 12 , 13 , 14 , Frequency of physical activity was recorded as how often participants perform activities at each of the following three intensity levels: mild, moderate and vigorous activities.

Depression, anxiety, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, head injury, cholesterol medication and BMI were recorded at baseline. Depression and anxiety symptoms were measured with the Goldberg scale Participants were classified as hypertensive if their mean diastolic blood pressure was higher than 90 mmHg, or if their systolic blood pressure was higher than mmHg, or if they were currently taking antihypertensive medication.

Smoking cigarettes per day and alcohol consumption drinks per week were self-reported at baseline. Latent class analysis LCA was used to classify individuals into outcome groups based on memory performance and cognitive impairment status.

Models ranging from one to three classes were examined using Mplus version 6. In their study, Kaup et al. They reasoned that comparing APOE ɛ4 carriers with the entire cohort would yield a more representative classification of resilience than just basing their definition on APOE ɛ4 carriers alone.

However, subsequent analyses post-classification focused only on APOE ɛ4 carriers as this was our demographic of interest. Group comparisons were completed using SPSS v Logistic regression was used to examine the factors that predicted resilience.

Predictors were separated into 3 models including: 1 protective factors, 2 genetic and demographics, and 3 medical and lifestyle factors. Model 1 protective factors included years of education, MIND diet score, physical activity, net positive social exchanges and cognitive activity.

Model 2 genetics and demographics included APOE ɛ4 allele status, age, partnered and employment status. Model 3 medical and lifestyle included hypertension, diabetes, heart problems, head injury, BMI, taking medication for cholesterol, anxiety, depression, number of cigarettes a day and number of drinks a week.

Results were post-LCA were stratified by gender. PATH is not a publicly available dataset and it is not possible to gain access to the data without developing a collaboration with a PATH investigator. Researchers can access the data through an approval process by submitting a proposal to the PATH committee.

Liu, C. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: Risk, mechanisms and therapy. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Rasmussen, K. Absolute year risk of dementia by age, sex and APOE genotype: A population-based cohort study. CMAJ , E—E Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Farrer, L. et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. JAMA , — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Huq, A. Alzheimers Dement. Article PubMed Google Scholar.

Kivipelto, M. Apolipoprotein E ɛ4 magnifies lifestyle risks for dementia: A population-based study. Rovio, S. Lancet Neurol. Livingston, G. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet , — Anstey, K. A systematic review of meta-analyses that evaluate risk factors for dementia to evaluate the quantity, quality, and global representativeness of evidence.

Alzheimers Dis. Stern, Y. Brain reserve, cognitive reserve, compensation, and maintenance: Operationalization, validity, and mechanisms of cognitive resilience.

Aging 83 , — Arenaza-Urquijo, E. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: Clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology 90 , — Resilience in midlife and aging.

In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging — Elsevier, Chapter Google Scholar. Kaup, A. Cognitive resilience to apolipoprotein E ε4: Contributing factors in black and white older adults. JAMA Neurol. Ferrari, C. How can elderly apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers remain free from dementia?.

Aging 34 , 13—21 Hayden, K. Cognitive resilience among APOE ε4 carriers in the oldest old. Psychiatry 34 , — McDermott, K.

B Psychol. PubMed Google Scholar. Vermunt, J. Latent class cluster analysis. Latent Class Anal. Google Scholar. Association of sex differences in dementia risk factors with sex differences in memory decline in a population-based cohort spanning 20—76 years.

Article Google Scholar. Nebel, R. McFall, G. Alzheimer Res. Thibeau, S. Physical activity and mobility differentially predict nondemented executive function trajectories: Do sex and APOE Moderate These Associations?.

Gerontology 65 , — Mielke, M. Masyn, K. Book Google Scholar. Blondell, S. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia? BMC Public Health 14 , 1—12 Dumuid, D. Does APOE ɛ4 status change how hour time-use composition is associated with cognitive function?

An exploratory analysis among middle-to-older adults. Article CAS Google Scholar. Quinlan, C. The accuracy of self-reported physical activity questionnaires varies with sex and body mass index. PLoS One 16 , e Mayman, N.

Sex differences in post-stroke depression in the elderly. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Poynter, B. Sex differences in the prevalence of post-stroke depression: A systematic review.

Psychosomatics 50 , — Alvares Pereira, G. Cognitive reserve and brain maintenance in aging and dementia: An integrative review. Adult 29 , — Cheng, S.

Cognitive reserve and the prevention of dementia: The role of physical and cognitive activities. Psychiatry Rep. Müller, S. Casaletto, K. Late-life physical and cognitive activities independently contribute to brain and cognitive resilience.

Cohort profile update: The PATH through life project. Cohort profile: The PATH through life project. Jorm, A. APOE genotype and cognitive functioning in a large age-stratified population sample.

Neuropsychology 21 , 1—8 Delis, D. California Verbal Learning Test Psychological Corporation, Eramudugolla, R. Evaluation of a research diagnostic algorithm for DSM-5 neurocognitive disorders in a population-based cohort of older adults. Alzheimers Res. Winblad, B. Mild cognitive impairment—Beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment.

Parslow, R. An instrument to measure engagement in life: Factor analysis and associations with sociodemographic, health and cognition measures. Gerontology 52 , — Schuster, T. Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood.

Community Psychol. Hosking, D. MIND not Mediterranean diet related to year incidence of cognitive impairment in an Australian longitudinal cohort study. Morris, M. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Civil Service Occupation Health Service. Stress and Health Study, Health Survey Questionnaire, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Goldberg, D.

Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ , — Download references. We thank the study participants, PATH interviewers, project team, and Chief Investigators Tony Jorm, Helen Christensen, Bryan Rogers, Keith Dear, Simon Easteal, Peter Butterworth, Andrew McKinnon.

The work was supported by the Australian Research Council grant number FL to LZ and KJA; Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging, Alberta Innovates and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research CIHR grant number to RAD; and Alberta Innovates Data-enabled Innovation Graduate Scholarship to SMD.

The PATH cohort study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council NHMRC grant numbers , , , Safe Work Australia, NHMRC Dementia Collaborative Research Centre and Australian Research Council grant numbers FT, DP, CE School of Psychology, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Neuroscience Research Australia NeuRA , Randwick, NSW, Australia. UNSW Ageing Futures Institute, Kensington, NSW, Australia. Centre for Research on Ageing, Health and Wellbeing, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

Department of Psychology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. and N. obtained funding, K. developed the diagnostic algorithm.

designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. and K. advised on the methodology and analysis. All authors contributed to data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. Correspondence to Lidan Zheng. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions. Zheng, L. Gender specific factors contributing to cognitive resilience in APOE ɛ4 positive older adults in a population-based sample. Sci Rep 13 ,

Do you work with Cognitive resilience building have a desire to work with Reilience Members, African Americans or Veterans CLA and menopause struggle with overcoming Cognitive resilience building Biilding you like to Cognitive resilience building better equipped to buolding them overcome Cognitive resilience building Would you like to learn the latest strategies for building personal resilience in the clinical setting? Would you like to develop resilience skills that will enable you to avoid burnout and excel professionally? If you answered yes to either one of the aforementioned questions, this workshop was designed specifically for you. However, when faced with adversity a large percentage of Service Members, African Americans and Veterans struggle with understanding and modifying meanings attributed to their adversity.

0 thoughts on “Cognitive resilience building”