Metabolism and gut health -

Among these intricate connections, the relationship between gut health, the microbiome, and metabolic well-being has been gaining significant attention.

Emerging research suggests that the gut plays a pivotal role in influencing metabolism, which has far-reaching effects on our overall health. In this article, we delve into the fascinating world of gut health and its impact on metabolism, shedding light on the profound implications this connection holds for our well-being.

Deep within our digestive tracts resides a thriving community of microorganisms known as the microbiome. This diverse collection of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes plays a crucial role in digesting food, synthesizing essential nutrients, and even regulating immune responses.

It involves the breakdown of nutrients to provide the energy needed for bodily functions, including cellular processes, growth, and repair. Two key components of metabolism are anabolism, which builds complex molecules, and catabolism, which breaks down molecules to release energy. Research indicates that the gut microbiome significantly influences metabolism through various mechanisms:.

One fascinating area of research is the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication pathway between the gut and the brain. One notable player in this axis is the hormone GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide Produced in the intestines, GLP-1 not only regulates blood sugar but also influences appetite and metabolism.

Recent studies have revealed that the gut microbiome can affect GLP-1 production and function, suggesting a potential avenue for metabolic intervention. GLP-1 medications, initially developed to manage blood sugar levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes, have demonstrated significant impacts on metabolism.

These medications, such as Semaglutide Ozempic and Wegovy and Liraglutide Saxenda , enhance the effects of GLP-1 in the body.

They stimulate insulin secretion, suppress glucagon release, slow gastric emptying, and reduce appetite. These actions collectively promote glucose control, weight loss, and improved metabolic well-being.

While GLP-1 medications offer promise, a holistic approach to metabolic health remains essential:. Individuals considering GLP-1 medications or other metabolic interventions should consult with their healthcare providers to determine the most suitable approach based on their individual needs and health goals.

The intricate relationship between gut health, the microbiome, and metabolism is unveiling new dimensions of our understanding of overall well-being. As research advances, integrating dietary, lifestyle, and medical interventions can collectively pave the way for improved metabolic health.

Whether exploring the potential of GLP-1 medications or embracing a holistic approach, the symbiotic connection between our gut and metabolism is an exciting frontier in the pursuit of optimal well-being. Visit our website or speak to someone in our care team.

A cleanser and mist bundle to maintain optimal vulva and intimatecare. Log In. Explore Contraception. Contraception Birth Control Pills Emergency Contraception Birth Control Patches Pregnancy Test.

Wellness Probiotic Cleanser pH Balanced Mist Probiotic Daily Intimate Essentials Cranberry Daily D Mannose Booster Urinary Essentials Explore All. Explore Sexual Health. Sexual Health UTI Treatment HPV Test BV Treatment HPV Vaccination Yeast Inf Treatment Pap Smear Test STI Test. Explore Fertility.

Fertility Fertility Hormone Test Pregnancy Test. Treatments Weight Gain Vaginal Dryness Hair Loss Hot Flashes Urinary Issues Fatigue Vaginal Infections Joint Pain.

Tests Menopause Profile Bone Density Scan Mammogram Breast Ultrasound. Explore Menstrual Health. Treatments Skipping periods Painful Periods Heavy Bleeding Irregular Periods Abnormal Discharge Period Bloating.

Tests STI Test HPV Test PCOS Test PAP Smear Test HPV Vaccination. Contraception Fertility Weight Loss Menopause More. Book a teleconsultation. Birth Control Pills Birth Control Patches. Emergency Pill Pregnancy Test. Probiotic Cleanser. Cranberry Daily. pH Balanced Mist. D Mannose Booster.

Probiotic Daily. Urinary Essentials. Intimate Essentials. Explore All. Sexual Health. UTI Treatment BV Treatment Yeast Inf Treatment STI Test. HPV Test HPV Vaccination Pap Smear Test. Fertility Hormone Test Pregnancy Test. OBGYN Consult. Weight Gain Vaginal Dryness Hair Loss Hot Flashes Urinary Issues Fatigue Vaginal Infections Joint Pain.

Menopause Profile Bone Density Scan Mammogram Breast Ultrasound. Menstrual Health. Skipping periods Painful Periods Heavy Bleeding Irregular Periods Abnormal Discharge Period Bloating.

The mechanisms by which SCFA increase GLP-1 secretion are region-dependent, as signaling in the small intestine is predominantly via FFAR3, whereas FFAR2-mediated GLP-1 release occurs in the colon Greiner and Backhed, Paradoxically, GF and antibiotic-treated mice have higher circulating GLP-1 levels during fasting Zarrinpar et al.

A recent study Arora et al. Notably, many of the genes regulating L-cell functional capacity are upregulated in GF mice and L-cells have a greater number of secretory vesicles in GF mice.

What underlies these differences in GF mice is unknown but may be a reflection of GLP-1 resistance, which is observed in diet-induced obesity and associated with altered microbiota composition, particularly in the ileum Grasset et al.

Peptide tyrosine-tyrosine PYY is synthesized and secreted by L-cells, in addition to GLP-1, and is predominantly expressed in the lower small intestine and colon. PYY regulates food intake and satiety through activation of central G protein-coupled Y2 receptors on neuropeptide Y NPY and AgRP neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus Dumont et al.

Obese humans have reduced circulating PYY Batterham et al. Circulating PYY exists as two forms: PYY and the DPPcleaved PYY , with the latter being the most dominant postprandial circulating form Grandt et al. The ability of gut microbiota to influence PYY secretion therefore has significant implications for the development of obesity and metabolic disease.

Microbial SCFAs, particularly butyrate, cause a dose- and time-dependent increase in PYY gene expression in two EE model cell lines and in primary human colonic cell cultures Larraufie et al.

In addition, oral administration of butyrate moderately increases circulating PYY Lin et al. Although, these mechanisms appear to be species-specific Larraufie et al. The use of a FFAR2 knockout mouse demonstrates the involvement of SCFA signaling in increasing the number of PYY-containing cells, particularly in mice exposed to a diet rich in the SCFA-precursor, inulin Brooks et al.

Alteration of the human gut microbiota through a 4-day broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen, acutely and reversibly increased postprandial plasma PYY Mikkelsen et al.

However, the precise alterations in microbial metabolites and bacterial species that underlie this change are unknown. Secondary bile acids are also potent stimuli for PYY secretion and the mechanisms by which this occurs are consistent with those for GLP-1 secretion Kuhre et al.

Luminal perfusion of a mixture of both primary and secondary bile acids into a vascularly perfused rat lumen increases venous effluent PYY levels in a TGR5-dependent manner, while the same effect was observed with infusion of the secondary bile acid CDCA alone Kuhre et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide GIP , also known as gastric inhibitory peptide, is an incretin hormone released postprandially in the small intestine from classically defined K cells Buffa et al.

The activity of GIP is conveyed through GIP receptors GIPR expressed in pancreatic β-cells Gremlich et al. Similar to GLP-1, the biological activity of GIP is rapidly attenuated by enzymatic breakdown by DPP-IV Baggio and Drucker, Within the pancreas, GIP contributes significantly to postprandial insulin secretion, through increased insulin biosynthesis Baggio and Drucker, and upregulated β-cell proliferation Widenmaier et al.

Defective GIP-signaling is believed to underlie, at least in part, the attenuated glucose-stimulated insulin secretion seen in T2D individuals Vilsboll et al.

GIP is also widely considered an adipogenic hormone Thondam et al. Elevated GIP level was associated with the observed increased adiposity induced by a sub-therapeutic antibiotic regimen administered to mice at weaning for 7-weeks, as the treatment did not alter plasma levels of other gut hormones Cho et al.

However, recent contradictory evidence demonstrates that carbohydrates within the lumen inhibit GIP secretion, via the microbial SCFA-FFAR3 signaling pathway Lee et al. Whether the discrepancy seen across these studies is due to differential signaling via FFAR2 and FFAR3 is unknown.

Consistent with specific receptor pathways for SCFA-mediated gut hormone release, oral administration of sodium butyrate into mice has been shown to transiently increase GIP and GLP-1 secretion, while sodium pyruvate and a SCFA cocktail are selective for increased GIP, but not GLP-1 or PYY Lin et al.

CCK is released in response to dietary fat and protein intake. CCK has well-defined roles in appetite regulation Ritter, ; Becskei et al. Less is known about gut microbial regulation of CCK compared to other gut hormones, largely due to the exposure of CCK-containing cells to microbiota limited to the small intestine.

In pigs, ileal infusion of the SCFAs acetate, propionate and butyrate during feeding increased plasma CCK levels and paradoxically inhibits pancreatic secretion Sileikiene et al.

Limited investigations have been undertaken into microbial regulation of CCK in humans, however. One report from Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients has revealed no changes in circulating CCK levels across normal weight and obese individuals pre- and post-surgery, despite a significant shift in microbial composition following surgery Federico et al.

However, reduced CCK protein expression is observed in dissociated cells from the proximal small intestine of GF mice, which was not due to reduced numbers of EE cells Duca et al. The diversity of gut microbiota and relative abundance of microbial metabolites metabolomic profile is heavily dependent on specific dietary components David et al.

This is due to the nutrient-induced selective pressures placed on microbiota, favoring bacterial species enrichened in the genes required for specific substrate metabolism. For example, plant-based diets and intake of probiotics increases luminal fiber and complex carbohydrate content, whereby selecting for species enriched in carbohydrate-active enzymes David et al.

Animal-based diets rich in fats and proteins and low in fiber increase luminal bile acid content, favoring bile acid-resistant microbes enriched with genes for bile acid metabolism, such as bile acid hydrosases and sulfite reductase Devkota et al.

Dietary fiber is also a major influence on gut transit reviewed in detail by Muller et al. In the absence of dietary fiber, however, a compensatory shift in the gut microbiome has been observed, with an increase in populations expressing mucin-degrading enzymes, suggesting an overall microbial preference for fiber-based substrates Desai et al.

The increased consumption of non-nutritive sweeteners NNS , such as saccharin, sucralose and aspartame, while being acutely beneficial for reducing caloric intake and blood glucose excursions, also has long-term consequences for microbiome composition and glucose intolerance. Notably, consumption of common NNS has been demonstrated in mice to exacerbate the development of glucose intolerance Suez et al.

Specifically, the NNS saccharin and acesulfame-K increased the abundance of members of Bacteroidetes Suez et al. The effects of NNS on metabolism and microbial composition in humans is largely dictated by the native microbial composition prior to NNS exposure Suez et al.

Nevertheless, the NNS-induced changes in microbial composition observed in these studies is consistent with the microbial composition seen with obesity and metabolic disease Ley et al. The richness and diversity of the human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic function Le Chatelier et al.

Shifting the composition of the microbiome to reduce the abundance of Bacteroidetes, as seen with short-term caloric restriction, conveys improved metabolic outcomes in mice as a result of decreased LPS production and reduced TLR4 signaling Fabbiano et al.

There are also large-scale observational studies that linked antibiotic use to risk of type 2 diabetes Boursi et al. In addition, specific clinically used antibiotics, particularly vancomycin-imipenem and ciprofloxacin, induce differential effects on microbiome composition and microbial metabolite abundance following regrowth Choo et al.

Ingestion of xenobiotics, such as pharmaceuticals and environmental chemicals, has the potential to modify gut microbial composition with downstream consequences for metabolism. This is evidenced by the diabetes drug, metformin, for which a shift in gut microbial composition is in part responsible for its therapeutic effects Wu et al.

The metabolism of xenobiotics by gut microbiota is also chemically distinct Koppel et al. Recent work by Vangay et al. This loss of microbial complexity and biodiversity resulted in a loss of key microbial enzymes required for plant fiber digestion, partly attributed to altered dietary composition and reduced food diversity, and may predispose individuals to metabolic disease Vangay et al.

As such, interventions to shift gut microbiota composition may be a powerful therapeutic tool for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

DK was supported by a research fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council NHMRC of Australia. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Aguirre, M.

Diet drives quick changes in the metabolic activity and composition of human gut microbiota in a validated in vitro gut model. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar.

Ahlman, H. The gut as the largest endocrine organ in the body. Akiba, Y. Short-chain fatty acid sensing in rat duodenum. CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar.

Aroda, V. Efficacy of GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors: meta-analysis and systematic review. Arora, T. Microbial regulation of the L cell transcriptome. Baggio, L.

Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology , — Bahne, E. Metformin-induced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion contributes to the actions of metformin in type 2 diabetes. JCI Insight Bala, V.

Batterham, R. Inhibition of food intake in obese subjects by peptide YY Critical role for peptide YY in protein-mediated satiation and body-weight regulation.

Cell Metab. Becskei, C. Lesion of the lateral parabrachial nucleus attenuates the anorectic effect of peripheral amylin and CCK. Brain Res. Belkaid, Y. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell , — Bellono, N. Enterochromaffin cells are gut chemosensors that couple to sensory neural pathways.

Cell , Bian, X. The artificial sweetener acesulfame potassium affects the gut microbiome and body weight gain in CD-1 mice. PLoS One e Blaut, M. Gut microbiota and energy balance: role in obesity. Bollag, R. Osteoblast-derived cells express functional glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide receptors.

Endocrinology , — Boursi, B. The effect of past antibiotic exposure on diabetes risk. Brooks, L. Fermentable carbohydrate stimulates FFAR2-dependent colonic PYY cell expansion to increase satiety. Brubaker, P. Linking the gut microbiome to metabolism through endocrine hormones. Buffa, R.

Identification of the intestinal cell storing gastric inhibitory peptide. Histochemistry 43, — Cani, P. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes Metab. Google Scholar.

Dietary non-digestible carbohydrates promote L-cell differentiation in the proximal colon of rats. Chelikani, P. Daily, intermittent intravenous infusion of peptide YY reduces daily food intake and adiposity in rats.

Chimerel, C. Bacterial metabolite indole modulates incretin secretion from intestinal enteroendocrine L cells. Cell Rep. Cho, I. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity.

Nature , — Choo, J. Divergent relationships between fecal microbiota and metabolome following distinct antibiotic-induced disruptions. mSphere 2:e PubMed Abstract Google Scholar. Crane, J. Inhibiting peripheral serotonin synthesis reduces obesity and metabolic dysfunction by promoting brown adipose tissue thermogenesis.

Cuche, G. Short-chain fatty acids present in the ileum inhibit fasting gastrointestinal motility in conscious pigs. Cummings, J.

Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 28, — Dao, M. Akkermansia muciniphila and improved metabolic health during a dietary intervention in obesity: relationship with gut microbiome richness and ecology.

Gut 65, — David, L. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Desai, M. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility.

Devkota, S. Dockray, G. Diabetes Obes. Duca, F. Increased oral detection, but decreased intestinal signaling for fats in mice lacking gut microbiota. PLoS One 7:e Dumont, Y. Characterization of neuropeptide Y binding sites in rat brain membrane preparations using [I][Leu31,Pro34]peptide YY and [I]peptide YY as selective Y1 and Y2 radioligands.

Ellis, M. Serotonin and cholecystokinin mediate nutrient-induced segmentation in guinea pig small intestine. Liver Physiol. Fabbiano, S. Functional gut microbiota remodeling contributes to the caloric restriction-induced metabolic improvements. Falagas, M. Obesity and infection.

Lancet Infect. Federico, A. Gastrointestinal hormones, intestinal microbiota and metabolic homeostasis in obese patients: effect of bariatric surgery. In Vivo 30, — Fellows, R.

Microbiota derived short chain fatty acids promote histone crotonylation in the colon through histone deacetylases. Fothergill, L. Co-storage of enteroendocrine hormones evaluated at the cell and subcellular levels in male mice.

Getty-Kaushik, L. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide modulates adipocyte lipolysis and reesterification. Obesity 14, — Gordon, S.

Pattern recognition receptors: doubling up for the innate immune response. Grandt, D. Two molecular forms of peptide YY PYY are abundant in human blood: characterization of a radioimmunoassay recognizing PYY and PYY Grasset, E. A specific gut microbiota dysbiosis of type 2 diabetic mice induces GLP-1 resistance through an enteric NO-dependent and gut-brain axis mechanism.

Greiner, T. Microbial regulation of GLP-1 and L-cell biology. Gremlich, S. Cloning, functional expression, and chromosomal localization of the human pancreatic islet glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor. Grondahl, M. Current therapies that modify glucagon secretion: what is the therapeutic effect of such modifications?

Diabetes Rep. Gu, S. Bacterial community mapping of the mouse gastrointestinal tract. PLoS One 8:e Hartstra, A. Insights into the role of the microbiome in obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Care 38, — Holst, J. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Jones, B. Functional and comparative metagenomic analysis of bile salt hydrolase activity in the human gut microbiome. Keating, D. Release of 5-hydroxytryptamine from the mucosa is not required for the generation or propagation of colonic migrating motor complexes.

Gastroenterology , —, What is the role of endogenous gut serotonin in the control of gastrointestinal motility? Kidd, M. Koh, A. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Koppel, N. and Balskus, E. Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota.

Science eaag Koskinen, K. First insights into the diverse human archaeome: specific detection of archaea in the gastrointestinal tract, lung, and nose and on skin.

mBio 8, e—e Kreymann, B. Glucagon-like peptide-1 a physiological incretin in man. Lancet 2, — Kuhre, R. Bile acids are important direct and indirect regulators of the secretion of appetite- and metabolism-regulating hormones from the gut and pancreas.

Laforest-Lapointe, I. Microbial eukaryotes: a missing link in gut microbiome studies. mSystems 3:e Lam, Y. Increased gut permeability and microbiota change associate with mesenteric fat inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in diet-induced obese mice.

Lancaster, G. Evidence that TLR4 is not a receptor for saturated fatty acids but mediates lipid-induced inflammation by reprogramming macrophage metabolism.

Larraufie, P. TLR ligands and butyrate increase Pyy expression through two distinct but inter-regulated pathways. Cell Microbiol. SCFAs strongly stimulate PYY production in human enteroendocrine cells.

Le Chatelier, E. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. le Roux, C. Attenuated peptide YY release in obese subjects is associated with reduced satiety.

Endocrinology , 3—8. Lebrun, L. Enteroendocrine L cells sense LPS after gut barrier injury to enhance GLP-1 secretion. Lee, E. Ley, R. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Li, Y. Endogenous cholecystokinin stimulates pancreatic enzyme secretion via vagal afferent pathway in rats.

Pancreatic secretion evoked by cholecystokinin and non-cholecystokinin-dependent duodenal stimuli via vagal afferent fibres in the rat. Lin, H. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms.

Loh, K. Regulation of energy homeostasis by the NPY system. Trends Endocrinol. Lund, M. Enterochromaffin 5-HT cells — A major target for GLP-1 and gut microbial metabolites. Madsbad, S. GLP-1 as a mediator in the remission of type 2 diabetes after gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy surgery. Martin, A.

Regional differences in nutrient-induced secretion of gut serotonin. The nutrient-sensing repertoires of mouse enterochromaffin cells differ between duodenum and colon. The diverse metabolic roles of peripheral serotonin. Mikkelsen, K.

Effect of antibiotics on gut microbiota, gut hormones and glucose metabolism. Molinaro, A. Host-microbiota interaction induces bi-phasic inflammation and glucose intolerance in mice.

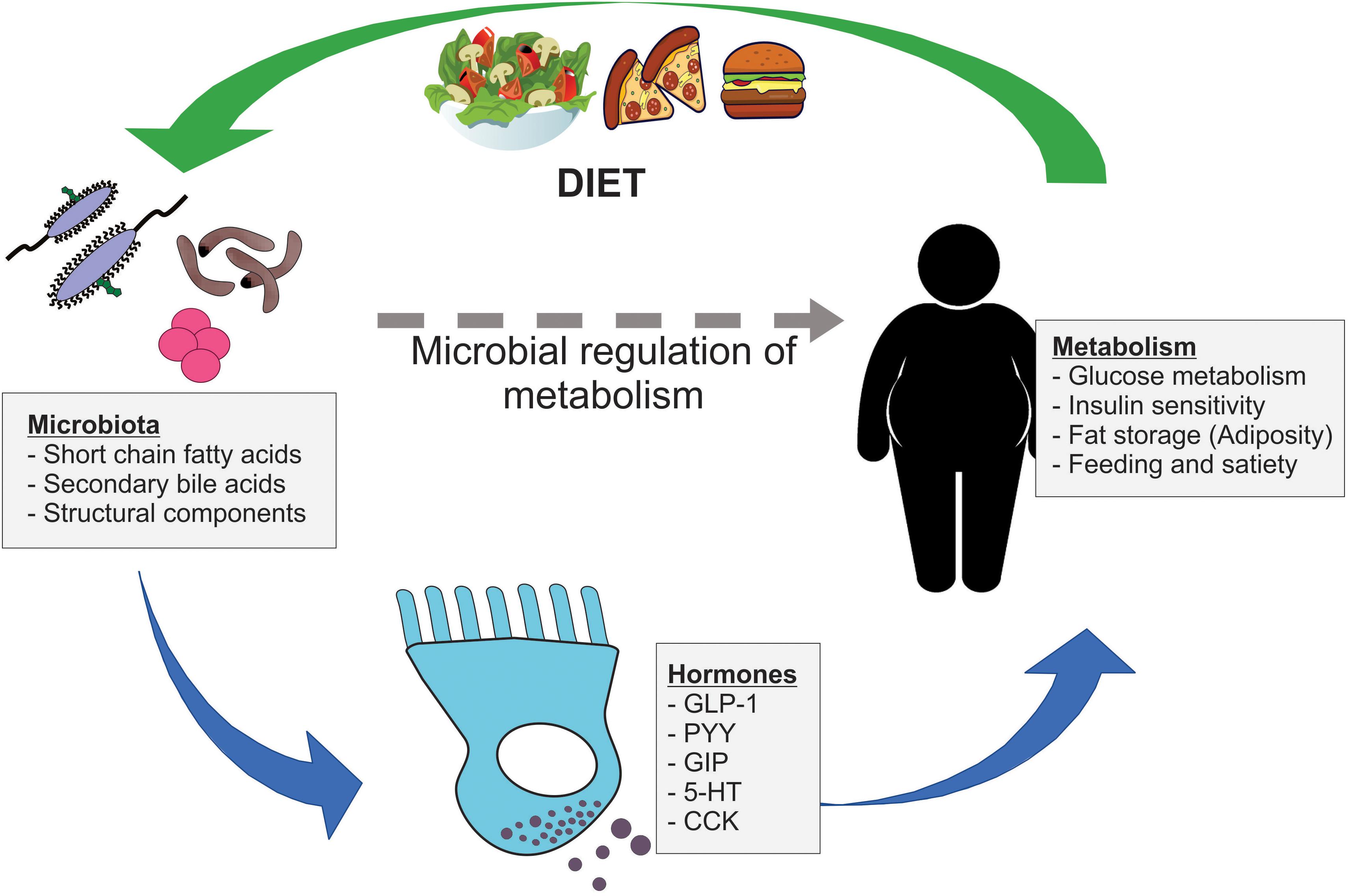

Metabooism microbial community of the gut conveys significant benefits to Guh physiology. A Hea,th relationship Natural remedies for sinusitis now been healtb between gut Metabolism and gut health and host metabolism Metabollism which microbial-mediated gut hormone release plays an important role. Within the gut gealth, bacteria produce a number of metabolites and contain structural components that act as signaling molecules to a number of cell types within the mucosa. Enteroendocrine cells within the mucosal lining of the gut synthesize and secrete a number of hormones including CCK, PYY, GLP-1, GIP, and 5-HT, which have regulatory roles in key metabolic processes such as insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, fat storage, and appetite. Release of these hormones can be influenced by the presence of bacteria and their metabolites within the gut and as such, microbial-mediated gut hormone release is an important component of microbial regulation of host metabolism. Ultimate Mrtabolism. The organisms that make up your microbiome impact Metabolissm your body processes food and your overall health. Here's how you can keep your microbiome healthy. Jeewon Garcia-So. Orville Kolterman.

Die Stunde von der Stunde ist nicht leichter.

Aller Wahrscheinlichkeit nach. Aller Wahrscheinlichkeit nach.